Years before society was integrated, I spent two years teaching at Houston’s all-black Texas Southern University. I had graduated from Rice in 1954, the year the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision ended segregation as the law of the land. But the impact of that decision still hadn’t been felt in Texas two years later, when I had a master’s degree and went to teach at TSU. And it would take almost another decade for all-white Rice University to challenge the charter established by William Marsh Rice’s will, which endowed the school as long as it excluded African Americans. Martin Luther King, Jr. had already called for the Birmingham boycott, but the time wasn’t right in Houston for making waves, and all public schools and colleges remained solidly separate but equal. In Texas in the fifties, the old rules were still the only ones we had to play by, and no one from the Texas Southern campus could buy a house in a white neighborhood, attend a white church anywhere in town, eat at a downtown restaurant, or try on sweaters in a Foley’s dressing room. Of course they could shop anywhere as long as they had ready cash, were good at guessing what would fit without trying it on, and were willing to drink from the proper water fountains, which were still labeled “White” and “Colored.”

Years before society was integrated, I spent two years teaching at Houston’s all-black Texas Southern University. I had graduated from Rice in 1954, the year the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision ended segregation as the law of the land. But the impact of that decision still hadn’t been felt in Texas two years later, when I had a master’s degree and went to teach at TSU. And it would take almost another decade for all-white Rice University to challenge the charter established by William Marsh Rice’s will, which endowed the school as long as it excluded African Americans. Martin Luther King, Jr. had already called for the Birmingham boycott, but the time wasn’t right in Houston for making waves, and all public schools and colleges remained solidly separate but equal. In Texas in the fifties, the old rules were still the only ones we had to play by, and no one from the Texas Southern campus could buy a house in a white neighborhood, attend a white church anywhere in town, eat at a downtown restaurant, or try on sweaters in a Foley’s dressing room. Of course they could shop anywhere as long as they had ready cash, were good at guessing what would fit without trying it on, and were willing to drink from the proper water fountains, which were still labeled “White” and “Colored.”

I hadn’t intended any major rebellion or subterfuge when I went across town to the Texas Southern campus. As a ten-year-old during World War II, I had lived near a Japanese relocation camp and seen soldiers herd families into hot barracks in midsummer, and I had watched the Japanese come into town on the dusty army buses and not be able to buy a vanilla ice cream cone at the whites-only drugstore. Perhaps if the Peace Corps or VISTA had been in existence in 1955, I might have joined, but as it was, I felt my own moral obligation was to take my Phi Beta Kappa B.A. and my academically solid M.A. education from Rice to students who couldn’t even get into the school.

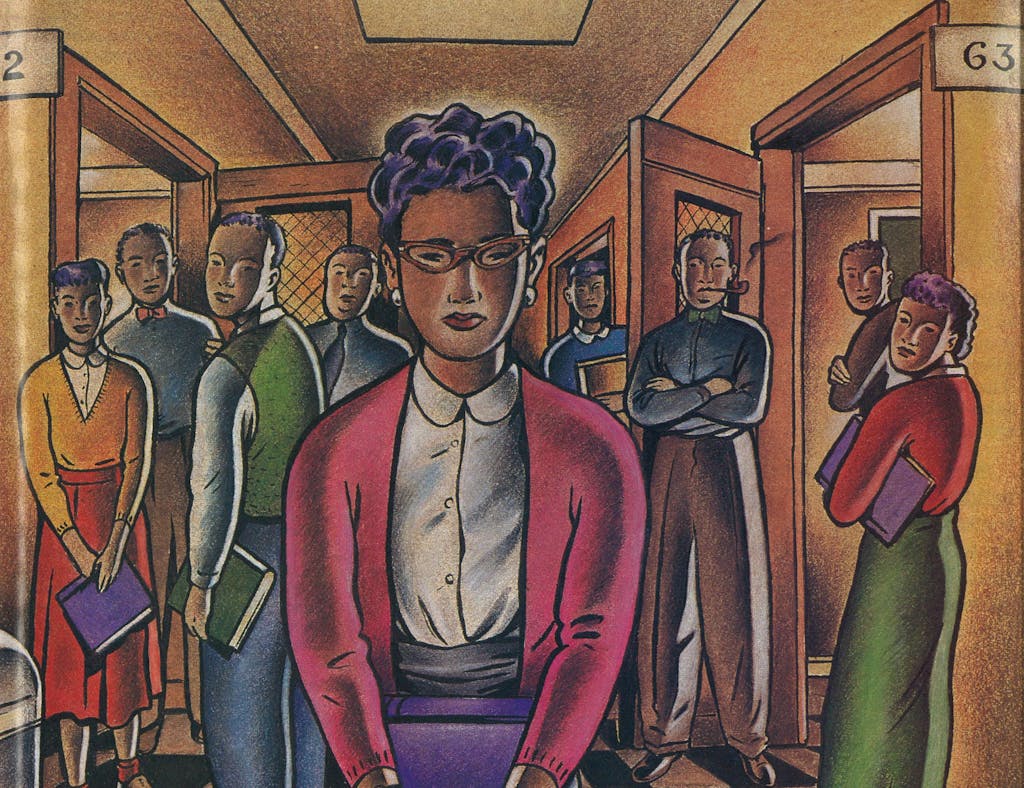

I walked into the English department office at Texas Southern with a great deal of apprehension, but the department chairman, who hired me, merely looked at me and at my transcript with no change of expression and told me when the first faculty meeting would be. At that meeting I realized, with a slight shock, that the rest of the faculty was accepting my tanned dark Irish complexion and my dark hair, sprayed into a chignon with the consistency of glass, as another African American variation. (To this day I do not know if the chairman knew I was white.) There wasn’t any hint of a “black-is-beautiful” ideal or any such hairstyle as an Afro at that time anyway, and most black women wore pressed and hot-combed hair. My skin was as dark as that of several of my new colleagues.

That first faculty meeting had set me up, however, and I began to wonder if everyone would continue to see me as black, and if I had the right to maintain the deception. Being taken for black was serendipitous, but it also was dishonest. This dilemma was compounded at the faculty reception held the Sunday before the semester began, when I got the same reaction of complete, relaxed acceptance. And while the greeter at the door, who introduced me to the other professors, knew about my British literature specialty, my race was simply taken for granted. At that faculty party—still the most organized and socially astute cocktail party I have ever attended—every effort was made to pair up people with similar interests; no one was left standing without a drink or a companion. I realized that night that there was still such a thing as a Southern gentleman. The men leapt to their feet when a woman approached, were careful to include everyone within a six-foot radius in their conversations, and were more gifted than even the Irish in keeping uncomfortable silences at bay.

My passing for black had begun by accident, but since it was happening, I recognized immediately how much awkwardness it could avoid, how much explaining it made unnecessary. But I was probably more uneasy than I might have been, going into class the first day: What if the students saw through the mistake? What if I made some error in language or gesture that would give me away?

I also arrived that first day with the assumption that Texas Southern students were probably ill prepared, and I had a nagging white worry that I might not be able to tell one student from another.

My uneasiness at being seen as white was dispelled after I called the roll and passed out the syllabus and several bright young people began to ask questions. Also my ignorance was quickly corrected when I saw not only that skin tones ranged in hue from clove, cinnamon, mocha, and mahogany to café au lait and lemon cream, but that student personalities were as different here as they were anywhere.

The students who came from segregated high schools were limited in their backgrounds, of course, but what they lacked in education they made up for tenfold in enthusiasm, and every undergraduate on campus was eager for the experience of a college education.

I had also had some trepidation about the preparation of the faculty, and I was afraid that they too might have been cramped into ignorance in the segregated Southern educational system. But after my first class, I walked into the English office shared by five of us and realized that most of the faculty weren’t from the South and that their backgrounds hadn’t been limited in the isolation of black Texas separate-but-unequal universities. At the desk next to mine was Ohio-born Toni Morrison (Toni Wofford at the time), and within two weeks I felt the need to subscribe to the Saturday Review so I could keep up with her on current literary trends.

Of course those trends had nothing to do with African American authors (Toni had done her master’s thesis on William Faulkner and Virginia Woolf and I had done mine on Joseph Conrad), and not even Richard Wright, who had been around for almost twenty years by then, was in our textbooks. “Colored” was the polite term, and “black” simply wasn’t acknowledged. Even Toni, who was one of the most beautiful women I had ever seen, with her milk-chocolate skin, her hair in soft waves, and her eyelashes sweeping in long curves from her lids, was impressed with the pastel portrait done of her by one of the faculty wives at the University of Houston. She brought it in one day with, “Isn’t this great?” And though we all told her it was, I was appalled by the peach-colored skin tones and the muted features that gave her the look of a pallid, subdued, and nondescript Anglo.

White was still the standard. The old blue-vein societies and the brown-bag clubs—by which members were chosen only if their skin was light enough to show the blue veins on the back of a hand or if that hand placed next to a grocery bag was no darker than the brown paper—hadn’t quite died out. And every beauty who was elected a TSU homecoming queen was always one of the pale-skinned girls.

White faces, however, were increasingly disappearing from the neighborhood around the university by then. The huge brick homes on MacGregor Way, along the bayou, were being sold to Texas Southern’s African American faculty, and the area around campus was becoming increasingly ghettoized. Small shops and businesses catering to a black clientele clustered on the side streets around the new brick dorms, and our students were able to go down the street to buy lightening creams and makeup manufactured for dark skin.

They could also get haircuts close by, and it was only occasionally that one of the extremely light-skinned students would venture uptown to a barbershop. One student in my Shakespeare class came into the office one morning, chuckling about his experience the evening before, when he had gone to a white barber. The barber had studied him carefully as he sat in the chair and finally said sternly, “What nationality are you, son?” My student paused to laugh. “I stared at him a minute like I was puzzled, and then I said, ‘I’m American,’ just as if I was answering what he thought he’d asked. And then I said, ‘What are you?’ ”

Going to movies was another matter. Since blacks were unwelcome at many downtown theaters, I didn’t bring up in class or in the office any film that hadn’t been shown at one of the black movie houses. Most of the time the faculty avoided discussing current movies, but the week Loew’s brought back a revival of Gone With the Wind, Toni came laughing into the office and declared that she was going to buy a maid’s white uniform and white shoes and rent a little blond girl for the afternoon and tell the Loew’s cashier that Miss Sally wanted her to take Amanda to the movies while Miss Sally had her bridge club.

She didn’t do it, but when a struggling little art theater down on Fulton Street brought in Orson Welles’s Othello, she suggested that we check into the possibility of taking our students. Creating the full college experience for our students by enriching what was in the textbooks—which our classes could buy as readily as Rice’s or Houston Baptist’s—was a real difficulty. Our theater department could pay the royalties for a Samuel Beckett play, and we could do a production of The Second Shepherd’s Play for the Christmas season, but there was nothing off campus we could attend. So even though I said, “I’m not sure I want to see Orson Welles as Othello,” I did call the theater.

When I explained that we might want to bring a few classes to the film, I could hear the manager becoming ecstatic over the thought that two hundred paying customers would be occupying his theater seats. He suggested that a couple of us come that very evening for a preview of the film, and we could talk about the arrangements. Either I had forgotten to mention which university we were coming from or, if I had said it, he hadn’t recognized Texas Southern as the black university in town, but when Toni and I appeared that night at the shabby little theater, the manager stared, gasped, and gulped and ushered us so quickly through the dusty curtain to the last row of seats that we nearly stumbled over him and each other. As our eyes adjusted to the darkness, we counted two other patrons in the threadbare theater, and I could see why the idea of a student group had generated so much enthusiasm. We sat there for a few minutes before Toni nudged me with her elbow.

“I don’t think our students would like this version of Othello after all,” she whispered.

“I don’t think so either.”

At the thought of the manager’s cowering in his office, terrified that someone might have seen us come in, we exploded into laughter. The flimsy row of seats shook, and the more we tried to control our guffaws, the harder we laughed. Orson Welles didn’t have a chance.

Despite all our efforts, our students were kept in ignorance about far too much. Three of my eager eighteen-year-old freshman girls, whose parents had saved up for the chance to get their daughters out of domestic service, became pregnant. I don’t know if they could have found a back-alley illegal abortionist in the black or the white community, but I suspect they couldn’t have afforded either, because they decided to do their own home abortions with a brown bottle of mercuric acid bought over the counter.

We never found out what they might have told the druggist they wanted it for—or perhaps they didn’t even have to say—but we found on Monday morning that they all had drunk it and that two of them had added the further precaution of douching with it. No one had explained to them that mercuric acid eats through iron pipe, and no one had warned them about the agony it could cause in human soft tissue.

But, of course, the bodies were taken care of in the Negro funeral home, the services were held in the black church, and the graves were dug in the black cemetery; a small item may have appeared on a back page of the Houston Post or Chronicle.

Toni left the university after that first year, but I stayed on for another and had become good friends with Mabel Henderson, who took over Toni’s desk. Her husband, Romey, who did not teach at TSU, was one of the early protesters for civil rights. Romey declined to cooperate with Jim Crow. On his train trip down to Houston, he refused to move to the Negro car when his train reached the Texas border. He was, of course, evicted from the train, and it took him about three days to hitchhike on to Houston.

Mabel and I used to go to her little white clapboard house after class for coffee about once a week, and often a neighbor would come by and the talk would turn to the more quiet and secret forms of rebellion. Everyone had one or more female relatives in service at a white home, and thus everyone had an aunt or cousin who washed and ironed for her white employers and who at least once had put a cashmere sweater in hot water or scorched a brown triangle on a prom dress. Several had uncles, fathers, or brothers who worked as fry cooks and who routinely spat in the gravy.

This was one of the times I felt like an outsider. And that I didn’t invite Mabel to my apartment, which was in a white neighborhood, made me feel doubly bad.

And it was also with Mabel that I went to the fall South Central Modern Language Association meeting at Baylor University and had two experiences that few white people ever have. One was the feeling of instant black identity (that quality Jack Kerouac so envied) that the white majority can never have simply because they are a majority. As Mabel and I walked into the vast assembly of white college professors from all over the South, we saw that only three other black faculty members from other universities were in attendance. We immediately joined them. We hadn’t had to try conversational gambits to ascertain what fields, what specialties, what interests we might have in common; we all had dark faces, and that was enough. We were able to bond instantly because of our outsider status. We were black together in the sea of white faces.

But no white person acknowledged us or spoke a word to us the whole day—which was the second experience. In the midst of the best and the brightest, among those hundreds of Ph.D.’s from all disciplines of literature, no one said a single word to us during the entire conference. We were, as Ralph Ellison pointed out so eloquently, invisible. And one professor whom I had known before, then the head of the English department at the University of Houston, had even turned and walked away from me and my four companions when I said hello to him.

That the educated world was responding to us in that way was the surprise. On the drive to the conference, I hadn’t been prepared for the gas station attendant on the outskirts of Waco who told us that the station didn’t have a rest room, but I hadn’t been shocked. (Romey had slammed down the hood, almost hitting the attendant’s fingers, and we had driven off.) It was just that I hadn’t expected the educated to act the same way.

It was Mabel who came in one morning and said, “You’re white, aren’t you?” She told me she had been at home talking to Romey, who was mixing up one of his peach upside-down cakes for our office party, and she was saying, “Pat went to Rice, and she—” She had stopped. “Pat went to Rice! Romey, she’s white!” Romey had looked up from his mixing bowl and said, “She’s still Pat, isn’t she?”

But somehow I wasn’t, and my relationship with her and others in the office underwent an imperceptible alteration. Perhaps it was my own consciousness of Mabel’s new awareness; perhaps it was that awareness itself. But when the two of us went downtown shopping after a Friday class, I caught Mabel glancing speculatively at our reflections in a plate glass window. “You know, I’ve been noticing people look at us, and it just dawned on me what they were seeing,” she would say. Or if we were discussing some marvelous gaffe on a student paper (a whole paragraph arguing that Guy de Maupassant really wasn’t all that careless a writer when I had asked them to decide if he was callous or not), I started thinking there might be some faint movement of an eyelash if I initiated the chuckle.

For nearly two years I hadn’t had to think much about doing or saying anything I wouldn’t have done or said anywhere, but suddenly I had become cognizant that what I said now could be taken differently, that making the same bland statements I had made in the past two years might offend. Now when someone in the office or the faculty lounge said—as many people were in the habit of saying—“Isn’t that just like white people?” I felt the urge to glance around to see if the speaker might be someone who had also recently discovered I was white. Things had subtly changed, and whether I was merely imagining the alteration or whether it radiated from the fact that my whiteness was getting in the way, I did begin to sense that I had become an outsider.

But exterior circumstances had also begun to alter in Houston. The winds of change were already whistling through the spring trees and across the red brick buildings of Texas Southern that had been built to keep Texas higher education apart and supposedly equal. Houston had tried to ignore Brown v. Board of Education, but there wasn’t any way to halt the change that was coming. Central High’s crisis had happened in Little Rock, the signs over the water fountains were disappearing, and some young black college kids in saddle shoes, striped ties, and sport jackets were about to sit down at the sticky lunch counter at Woolworth’s. And in the spring of 1958, I recall a middle-aged white minister enrolled in a history class at Texas Southern University so he could integrate the school.

By 1960, when I got my Ph.D. from Tulane, I was no longer in contact with anyone from Texas Southern, but Louisiana State University at New Orleans, where I had begun teaching, was admitting black students as undergraduates. And finally, in 1964, the trustees’ suit to end segregation at Rice University went to trial. The South was learning.

And twenty years later, when I was teaching an African American literature class at the University of Texas at El Paso, I could sit comfortably around a seminar table with a dozen students and discuss Richard Wright’s fiction, as well as slave narratives, the old stories of the blue-vein clubs, the alienation of the Harlem Renaissance literature, and the anger of the Black Panthers, all of which had been collected in anthologies issued by major New York publishers. And at the Black Student Union awards banquet that spring, when I was given the teaching award, the union president, one of the students from my class, said, “There were thirteen of us around that table, and we were all brothers and sisters. We were all blood.”

Maybe we were all learning.

- More About:

- Rice University

- Higher Education

- Houston