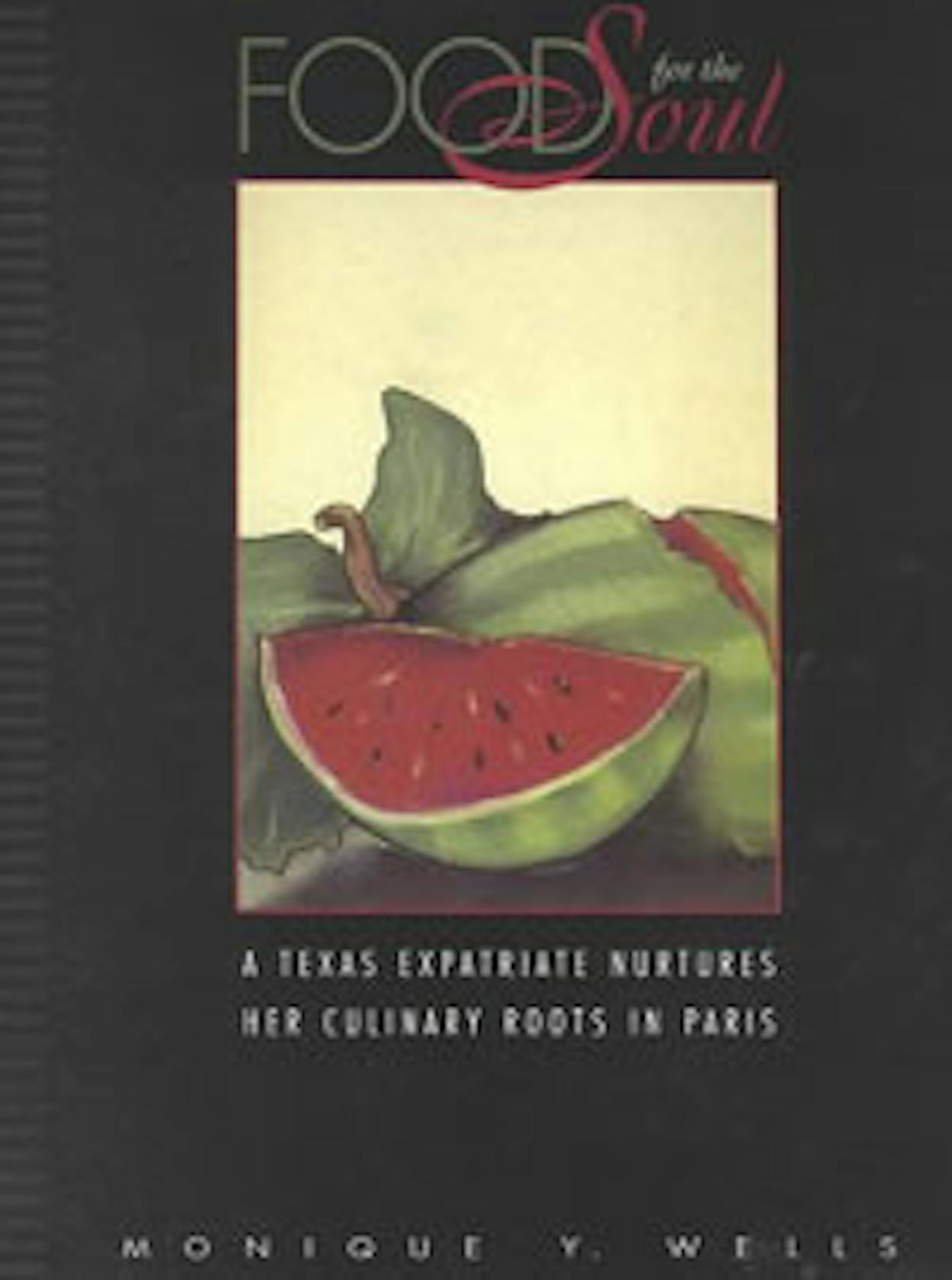

MONIQUE Y. WELLS’S FOOD FOR THE SOUL is a delightful cookbook that combines history and family recipes with food. Wells, a native of Texas, was inspired to write this cookbook after she moved to Paris, France, and began longing for the comfort food she grew up on. Because Food For the Soul was originally published in French, Wells took great pains to explain ingredients and measurements. In fact, she tells readers the difference between creole cooking and cajun cooking: “Cajun cooking is distinguished from Creole cooking by its more rustic nature. It is generally spicier and more ‘back-to-basics,’ while Creole cooking is more sophisticated and takes more care with presentation.” She also provides readers with a basic guide to chili, barbecue, and okra among other Southern mainstays. Even though most of the recipes in Food For the Soul come from family members, she states that variations on these recipes can be found in almost any Southern cookbook. Wells takes the reader from breakfast items like Baked Grits and vegetable dishes like Boiled Cabbage to poultry entrées like Chicken and Sausage Jambalaya and desserts such as Sweet Potato Pie.

We recently e-mailed Wells some questions about cooking and Food For the Soul. Read on to find out what the author had to say.

texasmonthly.com: When did you move to Paris and why did you decide to move there? Why the cookbook? Can you tell me a little bit about how it all got started?

Monique Y. Wells: I moved to Paris in June 1992 to work for the pharmaceutical company Rhone-Poulenc Rorer (now called Aventis). I have always been enamored of the French language, and after having studied it all my life (including a minor in college) and still not being able to converse, I decided that I should move to a French-speaking country to perfect conversational French.

Having launched my career as a veterinary pathologist in the U.S., I was prompted to look for a position in France after the company that I worked for in California (Chevron) decided to divest itself of its animal facilities. I began looking for a position in France at that time. It took two years of networking and a 1991 trip to France to visit companies and express interest in working there to find the position at Rhone-Poulenc Rorer. In fact, the day that I was leaving Paris to return to the U.S., I phoned an associate at the company to say good-bye. He told me that a person had resigned that same day, and he asked if I could come back for an interview. I came back within six weeks and began working within six months of that interview.

texasmonthly.com: You say in your book that you didn’t really enjoy cooking until you were in college. Do you have any suggestions to get young folks interesting in food and cooking?

MYW: I think that the best way to get young people interested in food and in cooking is to make food preparation an exciting experience rather than a chore. This means that the person demonstrating the food prep has to consider it exciting as well. Reveling in the colors, aromas, textures, and sounds of food as it is being prepared brings an awareness, a consciousness to cooking that is irreplaceable, not only for enjoyment but also for successful food preparation. Tasting while cooking is important too.

texasmonthly.com: In your book you state that you have a fondness for desserts and sweets. What is your favorite dessert in your cookbook? Why?

MYW: I love the Pineapple-Coconut Cake recipe in Food for the Soul, but I also love the Sweet Potato Pie. If I have to choose, I would say the Pineapple-Coconut Cake. It is a special-occasion dessert, and therefore something to look forward to. My mom’s favorite, though, is the Chocolate Quad.

texasmonthly.com: You define and bring to light many aspects of cooking that many cookbook authors seem to think is general knowledge. What prompted you to do the historical background on ingredients?

MYW: With the exception of the introduction, most of the historical information is on the origins of ingredients. In the introduction, I take greater pains to explain things like the use of volume instead of weight for measuring because my book was first published in French, and the French have a different way of measuring.

Also, many of the ingredients that are common to soul food are not known in France. The French eat very little corn or products derived from corn, like grits. They consider catfish as a fish that should be thrown back if caught. They do not eat okra. Only recently have they begun to eat sweet potatoes, and often, they are white sweet potatoes. I was trying to introduce French readers to new ingredients and to a new type of cuisine.

texasmonthly.com: How long did your research take? Where did you begin?

MYW: I began my research about four months after arriving in Paris—waking up one morning and thinking that I had to have grits for breakfast. This was all about comfort food. The honeymoon period of life in Paris was over, and I was becoming like everyone else—fed up with the post-summer vacation labor strikes (which I was to learn are annual!)—and trying to stay warm in a building where the heat wasn’t going to be turned on until a specified day, regardless of the ambient temperature. That morning, the thought of grits released a flood of culinary memories for me, and I determined that I would find grits and other ingredients for making food from back home.

texasmonthly.com: What was the most difficult aspect of putting this book together? Why?

MYW: The most difficult aspect was trying to get the book published. The writing of the book was sometimes exasperating when I had to push my mom or my cousin to give me a measurement for something that they referred to as “just a little bit” or “just enough so that.” But that was also the fun and the charm of writing the book. The research on the food items was fascinating and opened my mind to the possibility that history could actually be interesting. The worst part of all was trying to convince someone that the work was worth publishing.

texasmonthly.com: Although living in Paris is different than visiting, I’m guessing that most residents originally from other places sometimes get a craving for their native country’s cuisine. What dish from the States do you crave the most?

MYW: What you really cannot get in Paris is good barbecue. There is nothing on earth like Texas barbecue! And I rate my father’s barbecue as the best in Texas. There are other quirky things like yellow squash (Parisians only eat zucchini here) and seedless grapes (they are rare to non-existent).

texasmonthly.com: Have you found there to be an increasing interest in soul food in Paris since your book was published? If so, why do you think so?

MYW: I think that there was already a trend whereby Parisians were becoming more and more interested in foods that are not traditionally French when Food for the Soul was published. But the fact that Alain Ducasse wrote the preface for my book validated soul food in a sense. Once the book was out and the press became interested in it, I found that people were constantly asking me where they might taste soul food in Paris.

texasmonthly.com: What do you like best about cooking?

MYW: I like the creative process, the almost meditative experience of preparing vegetables and herbs for cooking, and the aromas coming from the kitchen when you feel as though you can’t wait another moment to eat.

texasmonthly.com: What do you like least about cooking?

MYW: Cleaning chicken and cleaning the kitchen after cooking a big meal.

texasmonthly.com: What is your favorite recipe in the book? Why?

MYW: My favorite overall recipe is Miss Grace’s Chicken and Onions. I like it because it is simple and because there is almost nothing better in this world than chicken and a great sauce over rice.

texasmonthly.com: How intertwined do you believe cooking and culture to be? Why?

MYW: I believe that the two are inexorably intertwined. What is culture but a conglomerate of where we live, who we encounter, how we interact, and what our beliefs are? Cooking reflects each and every one of these things—from the types of foodstuffs that are found in our native lands and the people throughout the millennia who have traveled and brought foodstuffs and methods of preparation of these foods to new lands to the rituals that have sprung up through interacting with others at meal time and the acceptance or rejection of food items based upon superstition or religious belief.

Because we cannot live without eating, and because for the most part, we don’t eat unless we cook, I don’t believe that we can separate cooking from who we are.

texasmonthly.com: Do you have any plans to do another cookbook? If so, what can we expect and when?

MYW: I have an idea for another cookbook, but I am keeping it to myself for the moment. To do what I would like to do for this book, I will need to spend a considerable amount of time in the States, and until I can arrange that, I don’t want to be scooped.

texasmonthly.com: Is there anything you would like to add?

MYW: Yes. I believe that Food For the Soul encompasses easy-to-understand, easy-to-prepare recipes, a tribute to my family (not only because of the recipes but also because of the family tree at the back of the book), interesting historical information, and an element of crosscultural exchange in a beautiful package. To my knowledge, there is not another soul food cookbook like it. With all this, plus a preface by Alain Ducasse, I hope that it will become a collectors item.

To purchase a copy of Food For the Soul, call 800-555-6771 or log on to parisfoodforthesoul.com.