This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

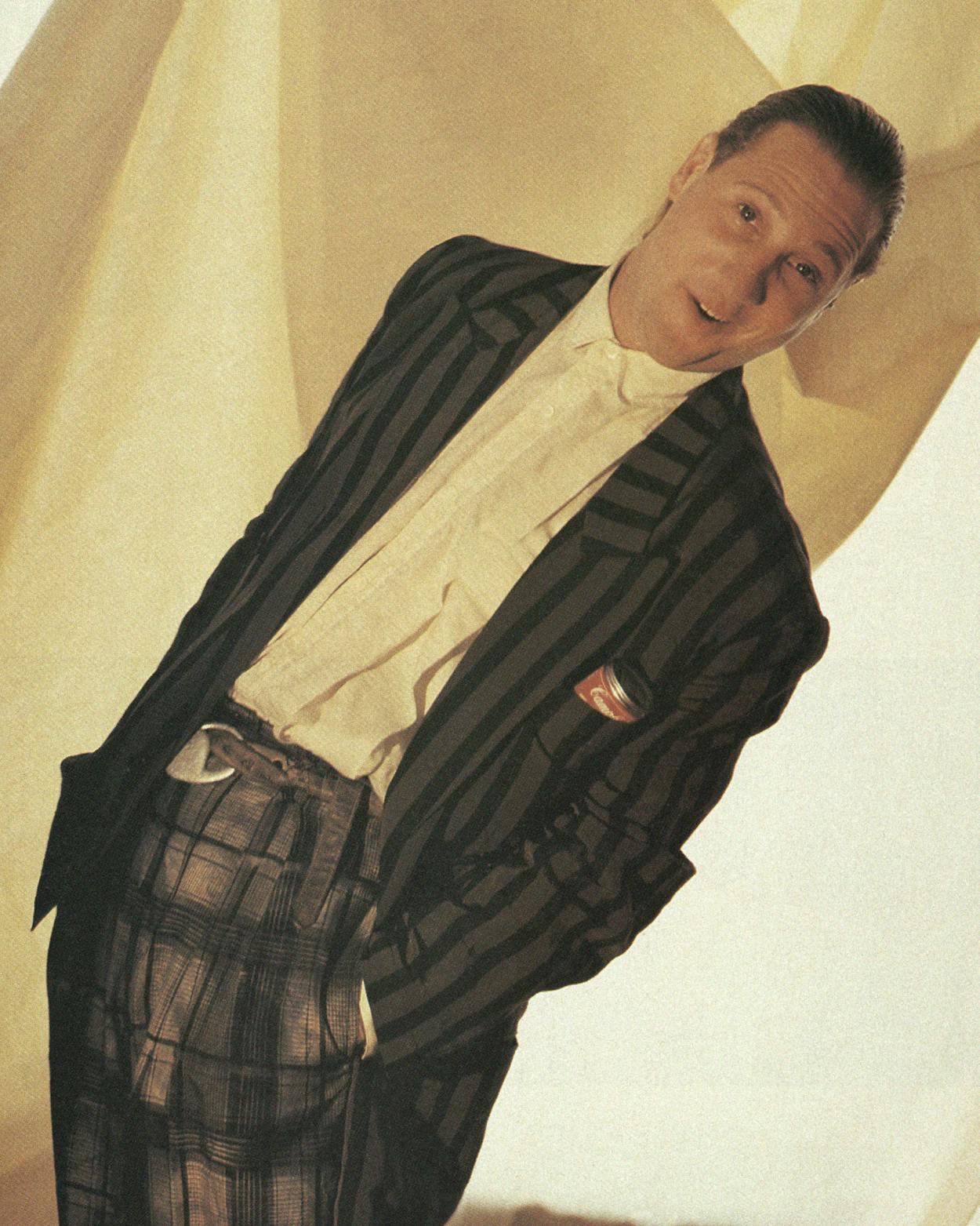

Here stands Eric Kimmel, bratty boy of early-eighties boomtown Dallas, publisher of Haute (the magazine Big D could never pronounce), purveyor of party pix, bill skipper, pill popper, dubious-fashion pusher, master manipulator, self-described sexual acrobat, probably the only publisher in the world who brags that he hates to read, and now prisoner 9961, charged with committing the biggest public screwup by a Texan abroad since Lyndon Johnson invaded Vietnam. Here stands Eric Kimmel, insisting that he isn’t stoned.

That’s big news from this dank little prison in Limoges, the French town of china fame. Because for most of his life, Eric Kimmel has definitely been stoned. On pot. On drugs. And, mostly, on himself. Getting stoned is, of course, what landed him here. He was busted in Paris for possession of five thousand hits of an Ecstasy-style designer drug in an insanely twisted scenario that could only have happened to the thirty-year-old Kimmel.

Throughout 1988 and early 1989 in Dallas, I had heard wild rumors, each mirroring a different part of the multifaceted personality I once knew: Eric, the feisty finagler, successfully exporting his technically-bankrupt-in-Dallas magazine and equally bereft persona to Paris; Eric, the naive nitwit, arrested for what was billed in the foreign press as Europe’s first Ecstasy bust; Eric, the cagey survivalist, becoming the ringleader of the most amazing jailhouse farce since Hogan’s Heroes, actually using French prisoners and social workers to publish a behind-bars book edition of Haute.

Now, after talking my way into a cramped visitor’s cubicle for a thirty-minute-limit chat, I must admit: The man the Dallas Times Herald once anointed as “the official ambassador to the night” is en forme.

Wildly animated and impishly handsome, with dancing eyes and a leer for a smile, he’s dressed in a mod shirt that resembles stained glass. In the cubicles around us, swarthy incorrigibles are ravenously kissing—and receiving big, forget-me-not hickies from—nubile gypsy women. But Eric is, to use his favorite adjective, the epitome of cool. His long, wavy hair is luxuriously ponytailed. His Levi 501’s are perfectly faded. His tan could challenge George Hamilton’s. And his mouth, as always, is working several topics at once.

“In Limoges,” he says, “they know three things about Dallas: the assassination of John Kennedy, J. R. Ewing, and me. They think I’m some international drug dealer. But I’m not. You gotta understand: I was arrested for the drugs, but I was really sent here for having too much fun, in life, in general. Too much f—ing fun. I was like . . . the Benetton of love. You know, women from every country. Did I tell ya that I was kicked out of a club called the Palace one night for screwing a really hot Jewish girl from New York on the bar?” Pausing for breath, he holds out a palm. “Gimme five, man.

“Being used to a lot of press, being a person who always had to make things look great even if they weren’t, my goal was to take this prison thing and make something good out of it. So I developed this attitude of ‘How can I make this work for me?’ And if you think like that, nothing can get in your way.

“Now I own this castle of crime! I have a color TV with cable, the best jam box in prison, all I can eat and drink. I’m tanning every day. I’d rather be in prison than in Dallas.”

Our thirty minutes vanish in a torrent of talk about the Dallas that didn’t understand him, the friends and journalists who “found it easy to rag me because they never made a move themselves,” the Paris roommate who finked on him, the French justice system that wouldn’t listen to him, and finally how he overcame all of this to find eventual personal redemption.

“God’s watching my ass,” Eric says. “I’d be dead now if I wasn’t supposed to be doing something cooool. I used to think I was lucky. Now I know I’m blessed. People like me, who live life rapidly, come out of prison changed: with shaved heads, giving head, and stuff. I’m coming out with long hair, kicking ass, and showing the world: Don’t f—with Texans, man!”

In a few weeks I would see Eric again, this time outside of prison. I figured he was up to his old habits of flagrancy and flakiness. But sometimes, when we would get crazy on Paris margaritas and late-night conversation, he seemed to embody the resiliency of the Texas spirit. But then, Eric Kimmel has a way of persuading people to his way of thinking.

Hey, motherf—ers!” Eric is addressing the room from the doorway of the Texas Coyote, a rowdy little Parisian Tex-Mex saloon whose owner-bartenders are from Lyons, whose jalapeños and tortillas are from Cognac, and whose jackhammer ambience is from the Mexican tequila that has transformed the predominantly European clientele into howling Texan wannabees. Only Eric Kimmel is authentic. And that’s the way he likes it.

In August 1989, three months after our prison visit, Eric is out on bail. Although he could easily sneak back to the States, back to Dallas and to freedom, he has adamantly remained in Paris, waiting to fight his case in a Limoges court. He’s staying against the advice of his Paris lawyer. Against the suggestion of the French justice system, which, Eric believes, hinted its advice when the authorities returned his passport. Against the pleas of his parents. And against the fatherly counsel of his “Mount Rushmore guys,” his young Dallas mentors like 8.0 Bar czar Shannon Wynne, who have all advised Eric to “get the hell out of France.”

“Leaving is a pussy way to go,” Eric explains. “If I leave, I can never come back to Paris. The justice system would like to see me leave because they made two big mistakes. The drug I was arrested for wasn’t Ecstasy, and it wasn’t illegal.”

But, for now, enough about the past. “Slammers!” Eric screams. The bartender slams a fizzy shot of tequila on the zinc bar while attempting a rebel yell. Eric drains his shot glass in an instant, then yells at the bartender: “Where’s your blond girlfriend, man? You were suckin’ her face last night like there was no tomorrow!” The bartender knows Le Texan, of course, as do most of the bar’s patrons. In his pre-bust days, they say, Eric would arrive—totally cool—to perform his specialty: the trade-out. In Dallas, it was free advertising in Haute for drinks, food, and fashions. In Paris, it was pills for tequila and tacos.

“He had crappy drugs,” laughs the Texas Coyote’s improbably named co-owner, Jean-Franfois Garcia.

“But nasty women,” says Garcia’s partner.

Now Eric says that he’s staying out of trouble. But he hasn’t ditched his hellion wardrobe. Wearing an outfit suitable for a heavy-metal rock star, he screeches his trademark cackle and, after downing another slammer, bounds off to the stairwell for a quick interlude with a passionate Parisian. He seems like the same old wild man. But now Kimmel is an expatriate of a Dallas that doesn’t exist anymore.

To know Eric Kimmel, you must understand the heady, opulent time in which he reveled. He calls it the Haute years, and he measures his reign by the opening of the original 8.0 Bar on July 13, 1980, until the club’s eventual shuttering on December 28, 1985, amid the oil bust. In those five years a Dallas of Roman proportions erupted. “It was when the Cowboys, the TV show, and the town were all doing great,” Eric says. “There was a spark in the air. It was a fireworks show every night.”

Among the glitterati was Kimmel, hyperactive bar mitzvah boy, waiter, and menswear salesman; aficionado of four-hour midday naps and thrice-daily baths and apparel changes; stepson of an upper-middle-class hypnotherapist. Eric is, of course, the best chronicler of his own legend. He traces the origins of his wild style to a haircut. Growing up in fashionable North Dallas, he was so shocked by the sight of his first barbershop haircut at the age of nine, he leapt out of the chair and ran for miles, eventually resting his P. F. Flyers in a black neighborhood, where he was apprehended for truancy. Two years later he was kicked out of Hebrew school for refusing to trim his long tresses. He also says that he lost his virginity at seven and almost shriveled his sex drive at fifteen, when a Jewish Teen Tour counselor ripped off the blanket under which Eric and a teenybopper were copulating on an airplane bound for Israel and screamed, “Eric Kimmel, you’re a disgrace to the Dallas tour!” His teenage years are perhaps best summed up by his first brush with the law: He was caught for mooning cars on the DFW turnpike.

Eric arrived in the new Dallas at nineteen, when he enrolled in fashion design at El Centro Community College and, with a fellow student as his partner, began staging fashion events. One night, drunk, he talked the owner of the Papagayo disco into having a small fashion show on a Saturday night. “The show turned out to be a smash,” Eric remembers. The next Monday, he dragged his partner, Richard Hand, to the Dallas Times Herald to toot their own horn. The following Sunday, Dallas’ first new wave designing duo was featured on the front page of the style section.

Eric Kimmel, still waiting tables, was on his way to becoming the Andy Warhol of the Metroplex, the perpetually penniless chief poseur of the too-much-cash, not-enough-class set, as impossibly wild and crazy as the inflated times. Driving a beat-up 1959 MGA, he lived, according to one observer, “in a port-a-can but acted like a king.” Fashion queen Kim Dawson called him “inventive and innovative” and introduced him to Trammell Crow’s Dallas Apparel Mart. And Eric dazzled ’em with spectacles like “White Trash,” a show of clothing made entirely of white plastic trash bags set to background obscenities from the movie Lenny.

After several months, Eric dropped out of El Centro and, with Richard Hand, opened a boutique, Eric Kimmel Designs. Six months later, the shop closed. “No money,” explains Eric. Hand left the apartment Eric had procured for him next door to his own and became the first of several disillusioned former partners.

Two days after closing the shop, Eric was hot on a new idea: a magazine. A fleeting local fashion rag he had advertised in had folded. Why not start his own? “I knew that Dallas’ photographers and models were frustrated. They were only able to shoot commercial crap and catalogs,” he says. “I also knew that the small specialty boutiques couldn’t afford to be visible in the expensive newspapers. I was going to be the one to put Dallas on the fashion map!”

He knew nothing about publishing, so he began fast-talking his new neighbor, Fred Center, a 22-year-old Neiman Marcus clothing salesman. “The walls were so thin, I could hear him every morning at five a.m., coughing, going to the bathroom, then heading over to my place,” Fred remembers. “He’d walk in, usually smoking a joint, dressed in rags or a sheet he’d slept in or in the baggy vintage clothes he’d worn the night before, his hair in a frizzy round mop, his mouth going a hundred miles an hour.” Fred Center knew no more about publishing than Eric did, but he had attended Syracuse University’s school of management. Most important to Eric, Center had an Ivy League look and the perfect name to play Eric’s straight man. “Fred could do all the stuff that I wasn’t good at, like business stuff and writing stuff,” Eric says.

The first issue of Haute appeared in June 1982, printed first monthly, then six times a year, then quarterly—always without a date since publication was never on time. Packed with party pix (Priscilla Davis at least once an issue), insipid articles (“Okay, you started at happy hour and drank your way right through the dinner hour”), and an Eric Kimmelsketched model on the one-color cover, Haute was, in short, as flighty and nighty as Eric.

And Eric was, of course, stoned, smoking an average of fifteen joints throughout the workday, never neglecting his naps, baths, or nightly club crawls. But from 1982 to 1985, he published 45 issues of Haute—increasing the magazine’s size from 32 to 96 pages and its print run from 4,000 copies to 15,000. He also produced two SMU coed-studded calendars, one issue of a nightly newspaper, three books (including a $50 party picture book with Dallas social lioness Ann Draper), and magazines for the Apparel Mart and print industry. “If I died tomorrow and my span of work was laid out, nobody could touch it,” he says. Eric claims credit for revitalizing everything from “Fashion!Dallas” (the fashion supplement of the Dallas Morning News) to Neiman Marcus’ parties to most Dallas modeling agencies—and for naming the areas of Exposition Park and Lowest Greenville. And he threw some of the best parties in town. So what if Haute never made money? Or that he was sued by a wholesaler who had bought the calendars and discovered that Eric hadn’t considered that 1984 was a leap year? Or that Eric got high with many of his advertisers but couldn’t pressure them into paying regular ad rates? “People who had a want to do something different, something new, I gave them an avenue, a stage, to do it on,” he says. “That was our magazine—newness.”

His philosophy? “You gotta shock people with style.” He wore the lone turban amid Dallas’ gray sea of Hickey-Freeman suits and used his hair like a neon sign: frizzed, pinned, bobbed, ponytailed, conked, Afro’d, and, eventually, bunned, like Robert De Niro in Angel Heart. His courting style was another part of his act.

“Eric and nineteen girls all dressed in white—the little Eric girls—would traipse into Nostromo with such incredible gall,” remembers Shannon Wynne, Nostromo’s owner. “He walked up and said, ‘Me and you are the only ones doing anything in Dallas. Let’s do it together. Let’s get on the comet and fly.’ He was like a nightclub on two legs. Wherever he went, things were buzzing. He knew all of the club owners, the bartenders, everybody. He lived on his magazine’s trade-out ability. I gave him dollar for dollar: drinks and food for advertising in Haute. Everywhere he went it was the same. Eric would say, ‘You want a drink? Does everybody want a drink? No problem. I can sign here.’ ”

But in the bleary dawn, Eric’s pockets would invariably be empty. “Totally irresponsible” is how most describe Eric’s relationship with money. Black-Eyed Pea restaurant pioneer Gene Street—attracted to what he calls “the most fertile, creative imagination I’ve ever met in my life”—says he invested $10,000 in Haute, then gave Eric a salary of $1,400 a month for several months and loaned him his 1976 Jaguar hardtop. “He said he’d produce three thousand to four thousand dollars a month out of Haute for my investment,” says Street. “But he traded out all the advertising, and there was no income. He sold the Jag and split for France. I figure he owes me forty thousand dollars. I’m adding seven and a half percent interest, and I intend to collect.”

The Bad Boy—Eric always loved that image. But while he vehemently denies accusations that he’s a financial flake, he was no match for the oil bust. Eric’s advertisers—the small, hip boutiques, salons, bars, and cafes—closed, leaving Haute’s accounts payable for their Chapter 11 papers. The partnership between Eric and Fred Center amicably split at the end of 1986. Haute was briefly rescued by Edwin and Debra Neill, a Springfield, Louisiana, couple who produced the annual Global Beauty and Fashion Show in Dallas. Eric fast-talked them into investing $60,000. The partnership lasted three issues. “By the third issue, Eric had gone to Paris,” recalls Debra Neill. “We had thirty thousand copies at a printer in Baton Rouge and just had to dump ’em, along with the whole project.”

In the Dallas of retribution, Eric’s badboy act didn’t play. Suddenly, people noticed that he was rude, crude, and, worse, he owed them money. He wrecked borrowed cars. His driver’s license was revoked. Bills mounted. Lawsuits loomed.

For a while he buried his problems in love. He cavorted with a starlet from Dallas, the only woman to have loved J. R. Ewing, Bobby Ewing, and Eric Kimmel. “But I knew it was time to leave the small town,” Eric explains. “Dallas was dead. The city was getting smaller. My reign was over. The Haute years had passed.”

In 1987, Eric’s ticket out arrived in the form of Hippolyte, a Paris-based boutique that had opened a shop in Dallas and wanted some media attention. After his Haute advertising spiel was snubbed, Eric advised the boutique’s manager, Jane Alexander, to stage a fashion show starring ten well-known Dallas bachelors. “All you have to do,” he said, “is give them each a suit.”

Eric delivered the bachelors, the press, and his usual glitzy crowd. His fee? A Giorgio Armani suit, shirt, and tie. The party was such a success, Alexander says, that when Hippolyte’s even hipper sister boutique, Beaubourg, was about to open, Eric was called to handle the party. “The boutique’s owner came in town from Paris and said, ‘Wow, this is really great. And you spent no money,’ ” Eric says.

The grateful owner then asked Eric the fateful question: “What do you want in return?”

Eric didn’t hestitate.

“Take me to Paris,” he said.

Eric Kimmel attacked Paris as he had Dallas: image first. When he arrived for his two-week, all-expenses-paid trip, he taxied to what would become his headquarters, an office-apartment in the heart of the Latin Quarter at 17 Rue de l’Ancienne-Comedie—the “ancient comedy” —the perfect name for Eric Kimmel’s madcap adventures in the City of Light.

“I brought five hundred issues of Haute with me to Paris and gave them to this American couple who sold magazines outside of cafes and bars,” Eric remembers. “They sold all the copies in three days. They called me and said, ‘Man, you got a really good magazine. You really ought to think about doing it in Paris.’ I thought, ‘My God, that’s the answer!’ Because we had this French name, Haute, which people couldn’t even pronounce in Dallas, why not move it to Paris and do it in English about Paris?”

By the time he returned to Dallas, Eric was buzzing with the concept for Paris Haute. “In Paris you shop by streets, not one mall or one store,” he explains. “Our concept was to go to several different streets an issue and sell each boutique on the street a page. We would do the photography and layout, an article about each street, so it would look editorial. But actually each page is paid for. With this concept, we would take in an extra thirty thousand dollars an issue. We would be the magazine to sell Paris to the world.”

We?

“Well, me,” Eric says. “When I say ‘we,’ I’m thinking me and the magazine. We come and we kick ass.”

Seeking a partner, Eric turned to yet another next-door neighbor in Dallas, a 29-year-old student, who spoke with me under the condition that his name not be mentioned in this article. They incorporated Paris Haute International, a Dallas corporation with an Austin accountant, a Paris business manager, the new partner as American copublisher, and Eric as Paris publisher, editor-in-chief, and promoter. “What closed the deal was the fact that I agreed to take my partner’s girlfriend to Paris as my translator,” says Eric. “She’d spent four years learning French, and her life’s dream was to come here.”

Today that’s all the two men agree on. Eric says his partner contributed $80,000 to launch Paris Haute. The partner says his contribution was only $5,000 and his name as credit for printing the magazine in Dallas and shipping it to Paris. Eric says his Paris Haute relationships in Dallas remain amicable. The partner says he never heard from Eric after he shipped Eric the first issue—and hopes he never does again.

For his move in late 1987, Eric packed up hip threads, press clippings, his partner’s girlfriend, and, oh yes, multiple hits of an Ecstasy-style drug called Heaven. The drug’s effect? Turning the user into an Eric Kimmel act-alike. “Everyone’s your best friend and you just wanna screw somebody really fast,” Eric explains. “It’s like a combination of cocaine and a Quaalude. Really metaphoric. You can sit and talk for hours to someone you don’t even know. The next day your jaw hurts from talking so much.”

Best of all, the pills were legal in France. Or, at least, Eric assumed they were. Like Ecstasy—the aphrodisiac of post-Haute Dallas as it slid down the economic drain—Heaven was legal until new laws were passed many months after its proliferation. “So I thought I had something that Paris didn’t even know about,” Eric says. But by the late eighties, France was becoming acquainted with designer drugs. After the Ecstasy-related death of the owner of a Paris nightclub, Ecstasy became the scourge of France, where it was referred to as the Death Drug.

Eric’s partner’s girlfriend lasted only a couple of months abroad. “She was miserable because Paris didn’t have diet drinks,” says Eric.

Eric Kimmel—who told skeptical friends that he would return home someday with bucks in his blue jeans and a beautiful Parisian on his arm—began a frenetic dance. Avoiding tourist haunts and monuments, he immersed himself in the beau monde and les branches (the “turned on”). “When I first met him, Eric didn’t have enough money to get a flat; he was living with an old girlfriend from Dallas,” says a Parisian photographer. “Within six months, he was paying seventy-five hundred francs a month for an apartment in the most beautiful part of the Latin Quarter.” How? Nobody knows for sure. Several different Dallas women say they contributed money for his move. Some contend that the borders between Paris Haute and Heaven—and Eric’s connections for dealing both—quickly became blurred; others claim naiveté was Eric’s only crime. He set up shop in a small office a boutique owner gave him as trade-out for advertising in Paris Haute and went to work. “My job was to meet people,” Eric says.

The key to Eric’s Paris? Drugs, sex, and rock and roll. Dressed in thrice-changed-daily “totally cool” clothing, shouting, “Let’s rock and roll!” in the morning, napping from seven to eleven at night, then screaming, “Shooters, slammers, and sex!” past midnight, Eric Kimmel became a regular in the palaces of Paris hip. “I’d ask everybody, ‘What’s cool? What’s cool? What’s cool?’ ” he remembers. “And I’d go to all the new places and meet the owners. Our magazine would be distributed to and supported by all of these people. I knew that I needed to come on in a really big way.”

“Here’s my card,” he would say on his advertising sales calls, handing the merchant a copy of Dallas Haute. “We’re starting a magazine in Paris. In English, about cool people and places and fashion. And I wanted you to be the first to know: The Texans are in Paris to stay.”

The Parisians were impressed. “Being a Texan helped me ever so much,” Eric says. “They have a fixation with Texas here. But everybody thinks westerns, cowboys, hats, accents. And I’m here in Gaultier and Yohji Yamamoto with a sleek magazine. It blew their minds. They couldn’t believe I was more hip than hick.” He completed a catalog for Hippolyte and a forty-page Paris Haute prototype. He persuaded designers Marithe and Franfois Girbaud to put their catalog in a back pocket of Paris Haute for a fee of $1.62 a copy ($25,000)—the first figure that popped into Eric’s mind. Fashion king Jean-Paul Gaultier received Eric enthusiastically. As in Dallas, Eric assembled a network of freelance writers and photographers, paying paltry fees or nothing at all for articles and only film costs for photographers, using the promise of exposure and total creativity to lure the young and striving onto his pages.

“I knew everything!” he says. “I had twenty-five photographers! Fourteen writers! I knew every place, and not just the place, but the owners on a personal level! Paris was perfect; I had it wired. The Muslim grocer ran me a tab. The Greek restaurant downstairs gave me free ice and plates for my dinner parties. And when we’d do Mexican food, the crepemaker made giant crepes for our chicken fajitas. I was watching free movies at the cinema. I’d give the manager hash, and he’d let me get high inside. At my bank, they’d let me go overdrawn fifteen thousand to twenty thousand francs a month. Why? Who knows? I guess they liked me.”

And women? Eric sucks air through his teeth and sighs, “Oh, man!” at the memories. Women of all nationalities, he says, would approach him in broken English, saying only, “I want with you.”

Shortly after Eric moved to Paris, he made a trip home. As he had vowed, he was accompanied by a beautiful black Parisian, Mai Oliver, a “Eurafrican goddess,” according to the prototype of Paris Haute. Eric says that they could converse with each other “only in the international language of love.” When they walked into Sfuzzi, he says, “Everyone was just dyin’, because I did what I said I’d do.”

During his visit to the States, Eric says, he met with a “connection.” The subject? Heaven. “They don’t know about it in Paris!” he exalted. Eric says the connection owed him a couple thousand dollars and had been sitting on a hefty batch of Heaven since the U.S. market had collapsed.

After his return, Eric says, a woman arrived on his Paris doorstep with a big gift-wrapped package. Inside were six thousand hits of Heaven. Eric says the pills were given instead of the money the connection owed him. But Paris’ reaction to the drug was disappointing. “The pills weren’t strong enough for the French,” he says. “They were used to the real X.” So Heaven became Eric’s trading beads. He says he didn’t sell the pills; he bartered with them. Two pills to a bartender and free drinks would flow. Three to the owner of a restaurant mexicain and complimentary fajitas were soon sliding across his taste buds. One down the hatch of a beautiful woman and—voilà!—it was tumble time. In a year Eric consumed or gave away only eight hundred of the six thousand pills, he says.

Eleven months after Eric’s arrival, 15,000 copies of the first and only issue of Paris Haute rolled off the presses in Dallas and were shipped to Paris. Priced at $5.95, or 30 francs, the magazine represented some of Eric’s best work: eighty pages of ad-smothered black-and-white hip, filled with interviews, street tours, still-vapid articles, and, of course, plentiful party pix (Grace Jones in place of Priscilla Davis). Eric says the first issue cost $40,000 to publish and profits would have been $48,000 if he could have collected more than $78,000 from outstanding ad revenues and even more from newsstand sales. But Eric’s Paris Haute partner has a different story: “He required advertisers to pay one third on agreement, then another third, then another,” he says. “Unbeknownst to me, he was spending all of it. Somebody went over and said, ‘He’s going hog-wild. He has tons of money.’ And I thought, “Oh, no.’”

To christen his first issue, Eric planned a party at Les Bains, the Phillippe Starck–designed bathhouse turned night spot. Eric talked the management into a trade-out: free space and liquor from ten until one for a full-page ad in Paris Haute.

Eric designed everything: a thousand black-and-white invitations no bigger than postage stamps, walls lined with the black-and-white Paris Haute cover, black and white cookies, black-and-white ice-cream cones, and a totally hip guest list. “By ten-thirty the place was packed,” he remembers. “Seven hundred people, all great—magazine people, fashion photographers, Roman Polanski. People were just dyin’. All my restaurant and club friends were there saying, ‘You got a great clientele. How do you know all of these people?’ And I just sat back and smiled.”

Eric Kimmel, aspiring prince of Paris cool, had arrived. Two weeks later he was gone. The bust occurred on October 4, 1988, one day before he was to move into his office-apartment on Rue de 1’Ancienne-Comedie, where he had already stashed his Heaven pills along with the rest of his belongings. He had just fallen asleep after a night at the Texas Coyote and the Palace when the telephone rang. It was for Adrian Chalk, 23, a Sorbonne-educated Canadian who was Eric’s roommate, interpreter, and copy editor; liver of “a long, varied, and scandalous life,” according to Paris Haute s contributors page.

“I came home from the Palace at six-thirty in the morning. The phone rang at eight,” Eric recalls. “Two minutes later, somebody banged on the door, and Adrian says, ‘Eric, it’s the police.’ There were four of them. I was sitting in bed naked while they tore the place apart. I knew I had nothing there. I couldn’t figure out what they were doing.”

When the police dug up a small quantity of Heaven in Adrian’s bedroom, Eric says he went into shock. “Where the f—did you get those?” Eric screamed.

“The police said, ‘Get dressed.’ So I put on what I’d worn to the clubs: a black Yohji Yamamoto suit, these great Jan Jansen shoes. We went to the Paris police station, and they put me in a cell with, like, forty other people. The police interviewed me, and later I found out that Adrian told them where my other pills were, in my new apartment.”

Dazed, angry, confused, Eric pleaded innocence: “I didn’t think these things were illegal.” When he refused a police order to pose for a picture with a group of French prisoners, Eric received a souvenir of Paris: a dusty boot heel in the back of the Yamamoto suit, which Eric would wear throughout his first two months behind bars. That night, he slept on the floor with a newspaper for his coverlet. The next morning the cops told him he was going to Limoges.

“What the hell’s in Limoges?” asked Eric.

He didn’t find out until he was speeding down the road—he in one squad car, Adrian Chalk in another—and talked the cops into letting him converse with Chalk over the two-way radio. Eric remembers the conversation:

“Adrian, what the f—is going on?”

“I’m sorry,” said Adrian. “I stole some of your pills and gave them to Patrick Carrara [a Paris Haute illustrator], and he got busted trying to sell them in Limoges.”

On the way to Limoges, Eric braced himself for the worst. “Forget about rape, forget about fags,” he remembers. “All I was worried about was if they’d cut my hair.” When the squad cars pulled into the small town in central France at midnight, Eric Kimmel had become a federal case. The judge—proud of his hometown police force for making Europe’s first Ecstasy bust—alerted the media. The next day, when the prisoners were transferred to the prison, the little town went wild. “All these young girls were, like, oohing and aahing because here I was in these real cool blue glasses and Yohji,” says Eric. “I looked like a rock star.”

It was yet another case of Eric Kimmel’s law, in which the zaniest possible scenario always turns out to be reality. Eric’s Paris lawyer, Olivier Metzner, says the events leading to the bust went something like this: Adrian Chalk stole a few hundred pills from Eric, then gave or sold about twenty to Patrick Carrara, who took them to Limoges and delivered them to Marc Leoment, a local hash dealer whose phone had been tapped by the police after his girlfriend allegedly had an affair with a policeman. Patrick told Marc that he was selling pure Ecstasy. When Patrick was popped by the cops in the Limoges train station, he spilled his guts about Adrian and Eric. The judge ordered all three men to be held without bail.

During his first few days in jail, Eric was “shocked, totally pissed.” He worried about his family. He thought of the Dallas that had snickered at his escapades and now would have something to truly howl about. He thought of ad revenues owed him and how people would think, “He’s in prison. We don’t have to pay.”

But crammed in a cell with Carrara and Chalk, Eric soon experienced a familiar sensation: the birth of an idea. “I always think things happen for a reason,” he says. “So in that cell, I said, ‘I’m gonna do a book about this. Adrian’s a writer. Patrick’s an illustrator. I’m a publisher. We can do something together!’ I spent my first month and a half trying to talk them into it.”

Adrian and Patrick, however, were too upset to work. And Eric didn’t make things any easier. He smoked; they didn’t. He watched American TV shows on French cable all night long; they hated TV. He spent his time dreaming and scheming; they spent theirs fighting and screaming about who did what to whom.

“Patrick did my beating up on Adrian for me,” Eric says. “The best way to get those guys was to just sit back and be positive. Because they definitely weren’t.”

Two months after his arrest, Eric left Adrian and Patrick to share a cell with Christian, a Frenchman who had been busted for hash. “He had a record company and a rock band called Strange Love in Clermont-Ferrand,” Eric remembers. “And I put together a little press kit for his band.” In exchange, Christian taught Eric the meaning of “prison wealth,” sharing the magical gifts (Eric would rather not reveal what) his girlfriend smuggled into the jail twice a week on visitor’s days.

“I was having a really great time, just like I’d been doing on the outside,” Eric says, smiling. “Christian taught me little things. Like how to do foot Jacuzzis in the toilet. And how to set up the cell to go to the bathroom in private. He taught me a lot of French. And he had great food. He had money, and I had money from home. We could buy two beers a day from the prison canteen, and we’d save ’em. At the end of the week, he’d have fourteen and I’d have fourteen. And we’d just laugh our asses off. Adrian and Patrick were totally pissed off. I was having so much fun. They hadn’t even smoked a joint. They had nothing. And they were just dyin.”

Consider Eric’s daily prison routine: “I got up at seven, had hot chocolate. Watched CBS morning news at eight. Had private French lessons from eight-thirty to ten-thirty. A walk from ten-thirty to eleven-thirty. Lunch at noon. Nap from two to four. Ping-Pong or soccer until six. Dinner at six, and then TV. Exercise throughout the day in the cell. I bought a brand-new double-cassette jam box from the prison canteen. I had my music blasting before the guards even got to my door with breakfast.”

On Christmas Eve, 1988, as Eric sat in his cell, his friends and family worried over his fate. How little they knew! His cellmate had just been released and had left Eric all of his booty. That evening, Eric was enjoying a party for one that matched the intensity of his legendary parties in Dallas’ wonder years. “I had a huge smoked salmon, a pound of foie gras, special cheese from the mountains, country ham, oysters, shrimp, escargot, everything,” he remembers.

For dessert, there was the cake that Christian’s girlfriend had baked and iced with . . . well, Eric doesn’t want to say, except that it was “a magical cake.” Eric ate his first slice that yuletide evening, then a slice a day for twenty days. Just before midnight on Christmas Eve, he let out a cackle that shook the cell block. “I had the music blasting, and I was sitting there laughing—totally naked, which is how I always am when I’m home alone—and I thought, ‘Here I am in prison, where everyone’s thinking I’m dying, and I’ve got enough stuff to feed twenty people. Aren’t I the lucky one?’ ”

After polishing off his last piece of magical cake, another project bubbled into Eric’s mind: Haute Mama, a book volume of Haute, written and illustrated by a unique staff—the prisoners of Limoges—about their favorite topic. “Women,” Eric says. “A topic everyone could participate in. It’s the one thing every prisoner thinks about. It’s also something that people on the outside wonder about. I wanted to do something that I could sell on the outside.”

In early January, Eric’s accomplices were released on relatively low bails: 100,000 francs for Adrian; 50,000 for Patrick. Eric’s was set at 1 million francs ($180,000). On their way out of the prison, neither Adrian nor Patrick said good-bye. But Eric did. “I yelled out to them, ‘I’ll do more in prison than you guys will on the outside.’ ”

And then he went to work.

How did Eric Kimmel persuade a group of mostly illiterate inmates—crowded in cells he was forbidden to visit, speaking languages he didn’t understand—to work for him? The same way he persuaded boutiques to advertise in Haute: trade-outs. Receiving monthly money from home, he became the prisoner with everything: beer, cigarettes, sedatives he would hoard from daily rations, fresh fruit he bought in quantity from the prison canteen, Dallas Cowboys and Mavericks T-shirts he asked his mother to mail him. “I’d give,” he says, “but I’d also expect.”

To launch Haute Mama, Eric cornered Jean-Paul, the administrator of prison education and his French instructor, whose approval Eric needed to produce his book within the prison system. Eric advised him of his illustrious Haute past. But the teacher was dubious. “He said, ‘You had a magazine in Paris that was in English? Sure, I bet you did,’ ” Eric says. “Prisoners will say anything. So I met this social worker, Pascal, and had somebody send him a copy of Paris Haute. He loved it. He spoke to Jean-Paul and they said, ‘Okay, what do you want?’

”I had them write a letter describing the idea and distribute one to every cell. I got about a dozen responses, prisoners who could write, prisoners who could draw. I had all of the teachers talking to the classes, telling them my concept: They could write or draw anything they wanted about women. If they couldn’t write, we’d help ’em write. If they couldn’t draw, we’d help ’em draw. We’d do anything—”

We?

“Oh, hell,” he grins. “I mean me.”

He scanned the daily-walk paths and soccer fields for his staff. He calls them “the bad boys of the castle of crime,” men like Neu Neu, the AIDS-afflicted heroin addict, in and out of jail four times in eight months; the gypsy caught stealing tapestries from a museum; and a host of assorted junkies, punks, and petty thieves. But Eric wanted the works of forty prisoners in the magazine. So he started passing out the goodies.

“I recorded Edie Brickell, U2, and Phil Collins cassettes for all the prisoners, tapes with special covers and my name and Dallas address on them,” he remembers. “I was asking guys to do a lot for me. Thinking about women in prison isn’t an easy thing to do. So I had to do a lot of talking. I’d just give away tapes and say, ‘Hey, you gotta do it, man, you just gotta do it! ’ I knew that if I left with this book, then I would have accomplished something in prison.”

The project should have been simple. But because Eric insisted on creating a camera-ready book, he needed materials the prison didn’t have and refused to purchase. So Eric used $400 of his prison money from home.

The resulting publication—one thousand copies printed by the French prison system and distributed to judges and prison officials across France—is unique. At 56 pages, with the works of 22 prisoners, it’s bigger than most issues of Haute and infinitely more interesting. Like Haute, its cover is a black-and-white Eric Kimmel design with the words “Creation, as my only chance” in French and English, the letters curved in the shape of a pair of mammaries. Unlike Haute, the magazine boasts inspired writing (“I love them all, be they housewives or intellectuals, dedicated nurses or convivial socialites; nonetheless, I have a marked preference for those with pure-minded simplicity,” writes the one English-speaking prisoner in the otherwise totally French book) and dramatic drawings of the love of each prisoner’s life (Mother Teresa–style goddesses instead of Priscilla Davis and Grace Jones). It also marks a budgetary breakthrough: Eric Kimmel only lost $400.

On May 22, 1989, Eric celebrated his thirtieth birthday by making an astonishing declaration: He was hanging up his hash pipe forever. “I never thought I’d live to see thirty,” he says. “So when I did, I decided to not live in the same way. I’ve always wanted to make my parents proud of me, which I had done in the past. But now I knew everything was turning against me. I wasn’t learning the lesson I was there for, which was: Cut the BS. Quit screwing around.”

Eric was released on June 27, 1989, after the judge—pressured by lawyer Olivier Metzner’s argument that lab tests had finally proved that the drug was not Ecstasy but a combination of MDA and amphetamine cut with massive amounts of glucose and lactose—reduced his bail to 200,000 francs ($36,000). It was paid by family and friends. Eric’s accomplishments during his nine-month imprisonment? Haute Mama, half of an autobiography, artwork for a line of prisonesque T-shirts. Most important, he had sparked a transformation at the Limoges Maison d’Arret. Inmates who once avoided the scorching sun lay about, working on their tans. The sounds of Edie Brickell and the New Bohemians thundered out of their cell blocks. Soccer games were played in Dallas Cowboys and Mavericks T-shirts. And the once-lethargic prisoners, now the accomplished staff of Haute Mama, cheered their editor-in-chief as he headed past the bars into a tenuous freedom.

It’s dawn in Paris and Eric, sauced on Sauza, is unleashing a new spiel. After ravaging the night in practically every disco and pseudo taquería in town, the “totally franc-less” Eric has depleted my wallet to the last centime. Now he is trying to persuade me to move to Paris “right now!” and become his partner in publishing a guide that, he says, we’ll call The Paris Haute Guide to Cool.

“I’ll put you up,” he says. “Free. Forget the article. Come here, live a little. I’ll get a champagne company to pay for everything. Once we get a few pounds off of you, we’ll get you into fashion. Gianni Versace all the way! You’ll be having a heyday with the women! If I do that, would you write the guide? Would you? Would you? I don’t want to hear maybe.”

We’ve stumbled into the plaza surrounding the Pompidou Center, where new wave sculptures whirl in a mad circus. Perfectly coordinated with the funkiness that surrounds him, Eric races about the cobblestones in big black Jean-Paul Gaultier motorcycle boots, tugging on my shirt-sleeve and raving about the hell he’ll raise if he’s not set free. “I’ll make it hard for ’em not to give me justice; I’ll put up too much of a stink,” he says. “I’ll take a message to France: Don’t f—with Texans, man. If they think J.R. was a badass . . .”

He picks up a long black metal rod from the street used by sanitation crews to pry open sewer coverings. It s city property. But earlier, Eric had showed me an identical rod in his apartment, saying he planned to “stud it up” and use it as a staff: the Moses of cool leading a sect of one.

“Do you think wearing Yohji and carrying this cane at my trial will get ’em pissed?” he says with a laugh, ever the jokester. “Do you think my cool silver l.a. Eyeworks glasses, which just came out in last month’s Interview magazine, will get ’em mad? Do you think my tan will get ’em? Or my Tokio Kumagaï slipon shoes with no socks? Or that I’m not wearing underwear? I’ll walk in the courtroom with my cane, shaking my hair, wearing a button that says ‘J’aime Paris’ and ask the judge, ‘Hey, man. Where be my bitches?’ The worst he can give me is a one-way ticket back to Dallas.”

At two o’clock on December 11, Eric Kimmel went on trial—before a tribunal that included two female judges—in Limoges. The night before, he advised me by phone that he had changed his plans for trial apparel since our last drunken evening together: “I’ll dress conservatively, in a cool white Le Garage jacket, Yohji Yamamoto pants, a Thierry Mugler shirt, and, of course, my Batman belt buckle.” He fully expected to be exonerated and released.

Wearing his hair behind his ears, Eric argued his case calmly, coolly, intelligently for much of the four-hour trial: how he was incarcerated for a drug that he truly thought was legal; how he had paid for his mistake with nine months imprisonment, $36,000, and the crippling of Paris Haute; how he had become a model prisoner; how he at least deserved the privilege of not being sent home. No studded cane was in evidence.

The prosecutor argued that Eric’s six thousand Heaven pills weren’t merely for his personal consumption but that he was the front man, the “Big Fish,” for two “big, important American drug dealers,” the French Connection done backward. The prosecutor pushed for the maximum sentence: eight years and 50,000 francs, on the charge of importing and selling narcotics.

The verdict? Guilty. The sentence? Five years, three on probation, one year already served. The only theatrical aspect of the trial? Eight policemen grabbed Eric by his feet and shoulders and cuffed him in the courtroom, immediately beginning his second stint in French prison. Olivier Metzner says he could be out in as early as three to six months. But Eric can forget about Paris. Immediate expulsion was part of his sentence. Upon his release, the police will drive him, handcuffed, to the airport and escort him onto a plane headed home to Dallas.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Fashion

- Dallas