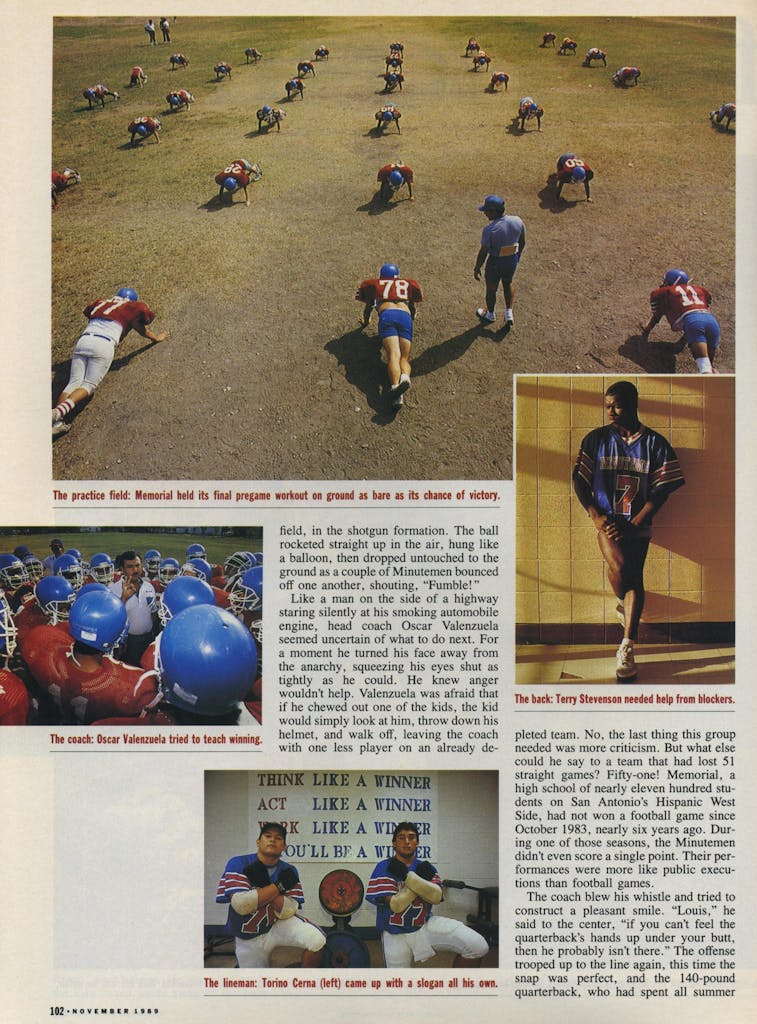

It was already Wednesday afternoon, the game of the year was just three days away, and an all-too-familiar sense of doom was sweeping over the practice session of the Memorial High School Minutemen. The offense broke out of the huddle with a clap, senior center Louis Hernandez bent over the ball, and on the proper count, he snapped it between his legs into what he thought were the waiting hands of the quarterback. Unfortunately, the quarterback, Edward Romo, wasn’t there. He was waiting for the hike seven yards away in the back field, in the shotgun formation. The ball rocketed straight up in the air, hung like a balloon, then dropped untouched to the ground as a couple of Minutemen bounced off one another, shouting, “Fumble!” Like a man on the side of a highway staring silently at his smoking automobile engine, head coach Oscar Valenzuela seemed uncertain of what to do next. For a moment he turned his face away from the anarchy, squeezing his eyes shut as tightly as he could. He knew anger wouldn’t help. Valenzuela was afraid that if he chewed out one of the kids, the kid would simply look at him, throw down his helmet, and walk off, leaving the coach with one less player on an already depleted team. No, the last thing this group needed was more criticism. But what else could he say to a team that had lost 51 straight games? Fifty-one! Memorial, a high school of nearly eleven hundred students on San Antonio’s Hispanic West Side, had not won a football game since October 1983, nearly six years ago. During one of those seasons, the Minutemen didn’t even score a single point. Their performances were more like public executions than football games.

The coach blew his whistle and tried to construct a pleasant smile. “Louis,” he said to the center, “if you can’t feel the quarterback’s hands up under your butt, then he probably isn’t there.” The offense trooped up to the line again, this time the snap was perfect, and the 140-pound quarterback, who had spent all summer throwing passes to the neighborhood kids to strengthen his arm, fired a pass ten yards over the head of his receiver. “Wow! That was a bullet, dude,” said an impressed teammate, nodding at Edward. Valenzuela looked down at a sheet of paper in his hands and decided it was time to try another play.

In this second week of September, the Memorial Minutemen were flirting with history. If they did not win within the next couple of weeks, the Minutemen would become known as the worst team in the history of Texas high school football. The state record for consecutive losses was 53, set from 1977 to 1982 by Kountze High School in East Texas. The record seemed like one of those sports milestones that would never be matched—equivalent, in its own way, to Nolan Ryan’s five thousand strikeouts. Yet here came the Minutemen, grinding away, relentlessly beating back the odds week after week.

Another coach refused to let his players wash their football pants until they won their first game. “That,” said Torino, “was a very smelly season.”

The 32-year-old Valenzuela knew he had one realistic chance of stopping the streak: It would come that Saturday night against the Knights of Holy Cross, a small private school just eight blocks from Memorial. Holy Cross was no pushover; it had won the Catholic district championship for the past two seasons. But twenty Holy Cross players had graduated last spring, and Valenzuela thought this year’s team was ripe for an upset. If anyone would know, he would. Valenzuela had been the Holy Cross coach before coming to Memorial last July. He knew all the Knights’ plays, he knew how their coaches thought, he knew what the players could and could not do. Suddenly inspired, Valenzuela marched toward the huddle and shouted one of the new slogans he was teaching the team: “If you practice like champions, you’ll play like champions!”

Torino Cerna, a starting offensive guard, looked glumly at his best friend, Rene Bocanegra, the starting tight end. Champions? Both Torino and Rene were seniors, captains of the team, and along with Louis, the center, they were the only ones who had been on the football team for their entire four years at school. Football was not that critical to their lives. They had no illusions about getting athletic scholarships to college, they didn’t need the sport to release pent-up adolescent energy (“Oh, man, we could get in fights after school if we needed that,” said Torino cheerfully), and they had learned long ago that Memorial football players weren’t treated with the swooning, doe-eyed adoration from girls that football players at other schools received. But at the beginning of each school year something drew them back to the parched practice field behind the school.

Though many of their friends had quit, too embarrassed to wear the red, white, and blue of the Minutemen, Rene and Torino would unhesitantly suit up, suffer through two-a-day practices, run wind sprints with out-of-shape teammates whose bellies bounced like jelly, and then stand by patiently while the coaches taught fundamentals like the three-point stance to the new kids, who usually would end up starting for the team because there was no one else to play. Why did they do it? Was it the hope that they would experience, at least once, the feeling of triumph? The taste of victory? “I don’t know,” Rene said. “I was in the sixth grade when Memorial last won a game, so we are all pretty used to losing. We don’t know anything else. I mean, I don’t even know how I’d act if we won.”

Coach Valenzuela, however, was adamant in trying to get the kids to believe in themselves. “You have to think like champions!” he exclaimed to the team. Torino rolled his eyes. He and Rene had watched a lot of coaches come and go. Valenzuela was the fourth in the last five years at Memorial—and had run the gamut of motivational techniques. One coach made the players give their jerseys to their favorite teachers to wear in class on game day to create a sense of school pride. Another coach, trying the opposite approach, refused to let his players wash their football pants until they won their first game. “That,” said Torino, “was a very smelly season.”

Valenzuela, though, tended to go for the big slogan, one the players would remember in the heat of battle. As the offense huddled again, the young coach leaned in and offered another of his favorite exhortations, “All right, guys, keep your poise!” The players responded obediently in unison, “Keep your poise!” Valenzuela told them to try a halfback sweep to the right, the Minutemen’s bread-and-butter play. The quarterback would pitch the ball to the best athlete on the team, junior Terry Stevenson, who would run madly for daylight. He was so fast he usually outran his blockers, which caused a slight problem once he got to the line of scrimmage. “The trouble,” summarized Terry, one of the five black players on the otherwise all-Hispanic team, “is that the defense is just standing there waiting to take my head off.”

This time the play worked perfectly, up to the moment when Edward Romo lateraled a little too low, causing the ball to bounce off Terry’s shin and dribble away. Valenzuela, already a portly man, swallowed a mouthful of air and looked like something stuffed by a taxidermist. “Come on, keep your poise!” he bellowed again, the words now more a curse than an exhortation. “Keep your poise” came the rather feeble response from the team. All at once, several yards away in the school parking lot, the Memorial Minutemen marching band, also practicing for Saturday’s game, launched into a rendition of “Tequila Mockingbird,” the feature piece at halftime and a rather peppy tune, even when played sourly. The band marched up and down, the notes echoing off the wall of the school and bounding across the field, past the football team, and into the neighborhood of small frame homes across the street. There the neighborhood dogs, who had been fenced in back yards all day, leapt up as one, inspired by the Latin tune, and howled soulfully back at the band. The doggie howls collided with “Tequila Mockingbird” at a point almost exactly over the offensive huddle of the Memorial Minutemen.

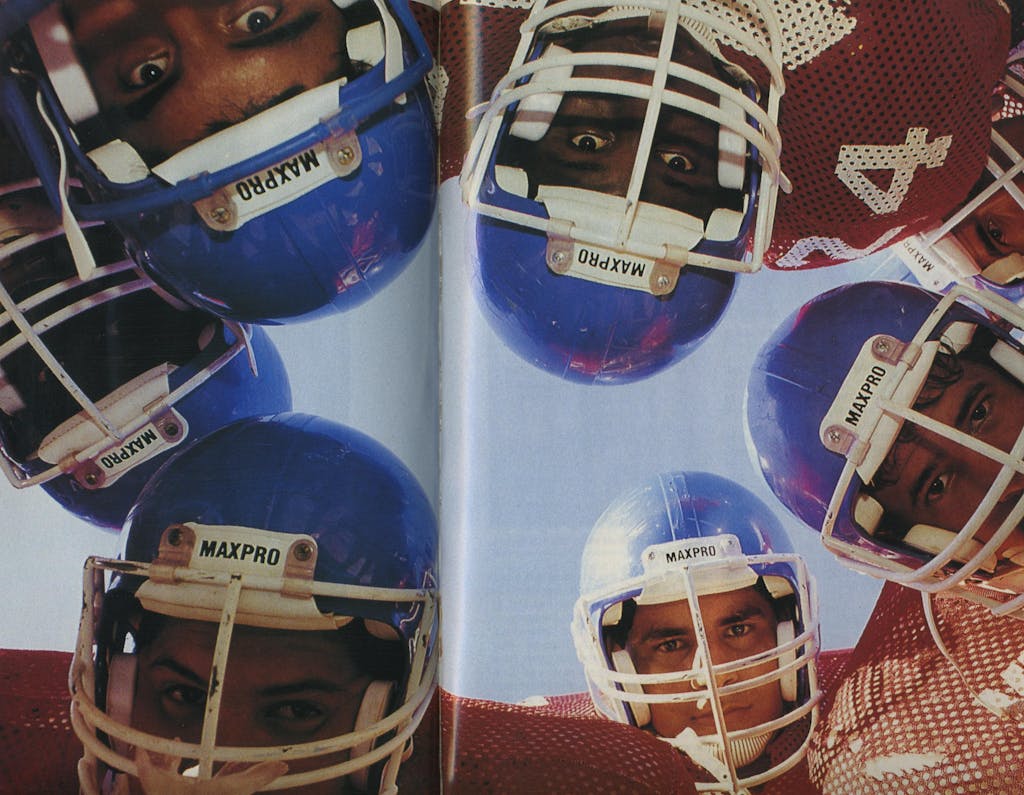

Valenzuela stared at his sheet of paper, trying to concentrate. The sun beat down on his head like a heat lamp. Around him were the confused but determined faces of his players, their bodies rocking wearily under their shoulder pads, the perspiration dripping from the bars of their face masks. They looked at their coach with great expectation, almost prayerfully, as if hoping that he could, through the force of his own will, get them to run a play correctly.

Then Valenzuela remembered the promise he had made to himself when the season began: No matter how bad things got, he would not act discouraged. He rolled up his sheet of paper, smiled broadly, and looked at his players. “We’re doing fine,” he announced, looking at no one in particular. “There’s nothing to worry about. Just try the play one more time.”

The offense glumly set up in formation, and Louis hiked the ball. Edward pitched to Terry. Terry raced around the end, staying on his feet even when one of his blockers, an offensive tackle, tripped slightly, lost control, and lurched into his path. For a moment it didn’t even matter that this was just another afternoon practice on a dusty field starving for grass. The Minutemen of Memorial High School were jubilant. “Okay, dudes,” shouted Torino. “We’re kicking ass now!”

“Kids at Memorial learn early that life is a bitch,” says Robert Rodriguez, a school counselor. “A football player just learns the lesson a little bit sooner.” No one has ever pretended that life at Memorial High School is easy. The kids come from poor or lower-middle-class backgrounds (over 80 percent of them are on a free or reduced-price lunch program). The school is part of the Edgewood Independent School District, which is poorer than all but nine of the state’s 1,055 school districts. Edgewood schools have trouble attracting and keeping good teachers because salaries are, on the average, $4,000 less than those of neighboring districts. Joe Sanchez, Memorial’s principal for the past seven years, is the lowest-paid principal at a public high school in San Antonio (making $39,902). The lack of money is felt even in the football program. The district spends only $37.75 per student for extracurricular activities while the richest San Antonio school district, Alamo Heights, spends $122.39.

As many as 20 percent of Memorial kids drop out each year. “I have some students who fall asleep in my class every day because they have jobs at night to help out their families,” says Eliseo Cadena, who has taught social studies at Memorial for seventeen years. “I have maybe seven students who are new to the country and can’t speak a word of English. I now have a new kind of Hispanic student, whose parents have left the Catholic church for these new fundamentalist churches. Those students sit in class and tell me that it doesn’t matter if they study because the world’s about to end anyway. Most of all, I have kids who figure it’s worth it to quit and find a job for five dollars an hour, because that’s what their dads do. They look at me and say, ‘Hey, you don’t make any money either’—and what can I say?”

Memorial, a square brick building constructed with few windows to discourage vandalism, is in the heart of the West Side barrio. The surrounding neighborhood reflects the traditions of both the older Hispanic families and the new generation of Hispanic kids. Two blocks from the school an elderly man has transformed half of his front yard into a religious shrine consisting of a statue of the Virgin placed in a cast-iron bathtub turned on its side. At the end of the school day he sits on his front porch and watches kids roar by his shrine playing rap music on their car radios. A few of the kids still wear rosaries, but as fashion accessories, not as icons. Old ladies, their faces shaded by parasols, take walks in the afternoons, past teenage girls wearing shiny flat black shoes, baggy pants, and blousy shirts—a look copied from the girls’ latest pop music idol, Paula Abdul. With a combination of gel and hair spray, the girls make their bangs stand up like water-ski ramps.

Many of the boys have formed groups that are more like fraternities than urban gangs, based solely on what kind of gimme caps they wear to school. Those who wear California Angels baseball caps are called the Aces; those who wear a cap that reads “Detroit Motor City” are the D’s; those who wear Yankees caps are the New Yorkers. The groups have no special codes of honor or turfs to protect; there have been no reports of drug-selling operations nor any particular pattern of violence. Mostly, they just hang out. “They aren’t putting the neighborhood under siege,” says principal Sanchez, “but these groups do act as a power base for kids who feel no power. It gives them an identity. But let’s be honest—they can become a problem. I know boys who have been friends since they were children, but now they won’t talk to one another because they wear different caps. Or two kids will get in a fight just because one’s an Ace and one’s a D.”

The modest neighborhood is mostly well kept, though down the street from the school is one house with a yard filled with couches and rusted bedsprings—the kids call it the Mansion. In fact, there is a small-town feeling here. Some residents sell raspas (snow cones) for 25 cents from their porches; others meet at the nearby icehouses to drink beer; some host all-day barbecues in their back yards every Sunday. Most of the little homes are surrounded by chain-link fences and a few have bars over the windows, but there is none of the suspicious, fearful tension found among neighbors in some inner-city neighborhoods. Residents seem subdued and used to their anonymity, as if they figure anything of importance will always happen somewhere else. “We never make the newspapers,” says Pearl Ramon, an eighteen-year-old Memorial senior. “You never hear about us except when someone over here gets in trouble—or when the football team loses.”

It is precisely that attitude, a lack of pride, that disturbs educators at Memorial. Sanchez estimates that 40 percent of Memorial’s students come from single-parent homes; a working single parent has little time or energy to provide the support a child needs. Moreover, the neighborhood around the school is aging. There is little new business, no new-home construction, and young families are moving out. “If you’re the slightest bit successful, and want to start a new life,” says Sanchez, “you try to get out of this neighborhood and move to the North Side. I think the kids who are left here feel they are getting left behind.”

Though Yvonne Guerrero, a perky junior cheerleader, is one of the popular students at Memorial, she too recognizes the frustration of life here. “To our friends from other schools,” she says, “the name ‘Memorial’ means something small. So you feel you’re small. It’s like—I don’t know—we feel we have a lower life or something.”

No one, however, can talk about defeat like the members of the Memorial football team. For them, it has always been the same old story. Each game would begin with unbridled enthusiasm, the players convinced that this time it would be different. Nevertheless, by halftime they would find themselves shuffling disconsolately into the locker room, already too far behind to catch up. Through the last six years the final scores have sometimes been astonishing: 70-0, 55-0, 54-0, 51-0.

When the losing streak began, in the seventh week of the 1983 season, Memorial was an average team that usually won as many games as it lost. “Because our school enrollment was getting smaller, we were having fewer guys come out for the team,” recalls Carlos Garcia, who took over as the team’s head coach in 1984. “We knew we would never be a powerhouse. But my God—this?” The 1984 team scored all of 29 points, which isn’t bad compared with the 1985 team, which scored none at all.

“We were outscored 330 to 0,” says Albert Cerna, the 1985 quarterback. Albert, who was also the senior-class president, still lives in the neighborhood and works as a vending-machine serviceman. “It was a nightmare.” Albert shakes his head like a dazed boxer trying to get up before the ten count. “Our biggest moment was when we scored a touchdown in the first game of the season, but it got called back because of a penalty.” In the last game that season, against Edgewood High, the other team’s star running back carried the ball on nearly every offensive play. The player was left in the entire game so he could set a new city rushing record of 476 yards. Edgewood won, 60-0. Coach Garcia was so furious that he refused to shake the Edgewood coach’s hand and then later quit as coach. “I was humiliated,” says Garcia, who now presides over a study hall. “I realized that I could not take it for one more minute.”

Another who wondered if he could take it was Albert Cerna’s little brother, Torino, who entered Memorial High in 1986 as a freshman. Torino was a natural lineman: He weighed two hundred pounds, enjoyed raw beef and chicken, and relished the opportunity to participate in a good schoolyard fight. Before entering Memorial, Torino and his friend Rene Bocanegra discussed Memorial’s prospects. Some of the area’s best players, whose parents could afford the $1,500 yearly tuition, were enrolling at private Holy Cross High School; a few had used relatives’ addresses to transfer to other districts and play for other schools. Torino and Rene decided to transfer, too, but their mothers wouldn’t let them. “I told my son that we had a duty to play for Memorial, win or lose,” says Juanita Cerna, one of those warm, always-cooking mothers, whose home has become the neighborhood hangout for the Memorial kids. “It was an honor, we said, just to play.”

Rene, a quiet, sweet kid—in many ways the exact opposite of Torino—got the same message from his mom. So off the boys went to practice. Memorial had brought in a new, hard-nosed coach, E. C. “Easy” Lee. He set up six-thirty weight-lifting sessions before school, held practice until dark, and tried the unwashed-pants experiment. None of that helped: The 1986 team scored only 20 points on its way to an 0-9 season. Coach Lee made practices even tougher for the 1987 team, which rewarded him by scoring 26 points for the year and going 0-10. Lee decided he had had enough.

For 1988, Memorial hired respected San Antonio coach Glenn Keller, who promised to stay until the team was a winner. In mid-October of that year the team lost fifteen players because of the state’s no-pass, no-play rule—they had failed courses in the first six weeks of school and could not play football. “I think a lot of players were trying to flunk,” says Rene. “We were losing so badly that a lot of them just didn’t want to be on the team.” After a disastrous season, including a 48-0 massacre by Somerset and a 35-0 defeat by Pleasanton, their losing streak stood at fifty, three games away from the record, and Keller thought twice about his promise. “When we heard he quit,” says Torino, “me and Rene just put our heads down and said, ‘We’ll never win one now. No coach will ever stay here long enough to teach us to win.’ ”

But last July, Memorial announced the hiring of Oscar Valenzuela. Valenzuela’s contract had not been renewed at Holy Cross—he had squabbled with the principal, and they both agreed it was time for him to find another job—so Memorial jumped at the chance to get him. He had grown up in the area, and he knew that the kids needed a coach who was as much a father figure as someone who could teach the X’s and O’s. “The majority of kids here aren’t ingrained with the winning attitude like kids from other schools,” Valenzuela says. “They don’t have fathers who come out to watch their practices. The booster club for the school has something like half a dozen members. Some of these kids are even embarrassed to tell people they play for Memorial.”

One of the first things Valenzuela did when he got to the school was put up in the locker room a stenciled sign of a slogan he had seen in a weight-training magazine: “Think like a winner, act like a winner, work like a winner, and you’ll be a winner.” But after the first day of practice, on August 14, even he had his doubts. Only 25 kids showed up—and one of those quit before practice was over because he got hurt. Some of last year’s players, like the starting quarterback, weren’t playing anymore. Except for center Louis Hernandez and Torino, there were no linemen with any varsity experience. “It was the same old situation,” remembers Torino. “I wondered why I was even out there again. But I said, ‘Oh, well, one more chance. ’ ”

Valenzuela, chagrined, would stare off into the distance, trying to come up with a plan to save the team. At one point he was staring off at the parking lot and saw a very large boy playing the trumpet with the band. His name was Ben Esparza, he weighed 230 pounds, and his father had encouraged him to stay off the football team and with the band because it would be a better experience than football.

“Boy, that’s an awful big kid,” Valenzuela would say over and over to his assistant coaches. They decided to recruit him. One day after band practice, Valenzuela sat down with Ben at the cafeteria and asked him if he wanted to “be with the men.” It was a tough decision. Ben, a junior, wanted to make all-district band before he graduated. He liked marching in formation, and he loved playing “Tequila Mockingbird.” Plus, he felt loyal to band director David Garcia, who had personnel problems of his own with just 55 band members. But when Valenzuela told Ben he could help Memorial do something it had not done in a long time—namely, win a football game—Ben was persuaded. Valenzuela had his starting offensive right tackle.

He anchored the defense with Eugene Salazar, a silent, fierce middle linebacker who had lived with an aunt in another school district the previous year because both of his parents had been sick with cancer. Valenzuela recruited a couple of other seniors who had never played a down of football; he started morning study halls so the players wouldn’t flunk out. He gave Rockne-esque lectures in which he would say, “If you feel you’re going to lose, you’re going to lose,” and at the end of practices, no matter how bad, he made everyone slap hands and say “Good practice.”

Frankly, the team looked miserable. It lost its opener to Somerset, 26-6, increasing the streak to 51 games. Holy Cross was next on the schedule. The local press began showing up to hear Valenzuela say magnanimous things like “Our goal is not to break the losing streak but to eventually turn this program around. We don’t even talk about the losing streak here.”

“That’s all we talk about,” said Rene Bocanegra a few days before the Holy Cross game, his eyes so intense they looked like BBs. “The streak. We’ve got to break that streak. If we don’t, we’ll never be able to live it down. Ever.”

Thursday afternoon practice came to a rather smashing conclusion. Edward Romo lofted a deep pass toward the end of the field where the defensive team was practicing, and his receiver, blindly pursuing the ball, ran headfirst into a linebacker—and Coach Valenzuela decided to let the boys off early. While the other players had their usual fun in the locker room—performing butt slides in the shower, singing rap and Mexican songs—Rene and Torino dressed quickly. The Cinematic Society, of which Rene was president, was meeting at the theater to see the highly praised movie Dead Poets Society. The film society’s sponsor, Dennis Stock, thinks the movies are a good way for Memorial kids to get a sense of life outside their own pocket of culture. There did seem to be a certain wonderful irony in a bunch of street-smart urban Hispanic kids watching a movie about life at an old New England upper-class prep school, where boys, to show their rebellious side, would sneak off to a cave, read poetry, smoke pipes, and talk about “sucking the marrow out of life.” The Memorial kids, most of whom had seen their share of drugs and crime, teenage pregnancy, and broken homes, silently watched the screen as the teacher, played by Robin Williams, taught his English class the meaning of the old Latin phrase carpe diem. “Seize the day,” Robin Williams passionately told his students, who were all wearing white shirts and ties.

Torino, wearing a gold earring and his D cap pushed back on his head, seemed to ignore most of the movie. He dug his hands into other people’s popcorn, teased the girls, and during a scene in which a teenage couple embraced on a couch, he whispered loudly, “That’s what I’m doing after the game. Maybe before.”

“Shhh,” said Rene, absorbed in the movie. There were times when Rene, the son of a millworker, would worry about what he would do with his life. Unlike many of his teammates, he wanted to go to college. He kept up a B average in school, didn’t drink because he had seen what it had done to some of his friends. He refused to join one of the school’s gangs. Last summer he had bused tables at the Bill Miller Bar-B-Q a few blocks from the high school, making nearly $2,000, much of which he spent on fashionable clothes: a $97 pair of Red Wing boots, Union Bay and IOU pants, and Polo and Girbaud shirts. Though Rene loved the neighborhood—he would hang around Torino’s house on weekends, going into Torino’s room to look at all the posters of pretty Hispanic girls in bikinis that Torino had put on his ceiling—he couldn’t help but wonder if he was meant for something more. “Maybe get married and have children, have a career, and move somewhere else,” Rene said. “I don’t really know.”

At one point in the film a student quoted a line of poetry: “Oh, to struggle against great odds, to meet enemies undaunted.” Rene bent forward and stared at the screen. The big game was less than 48 hours away.

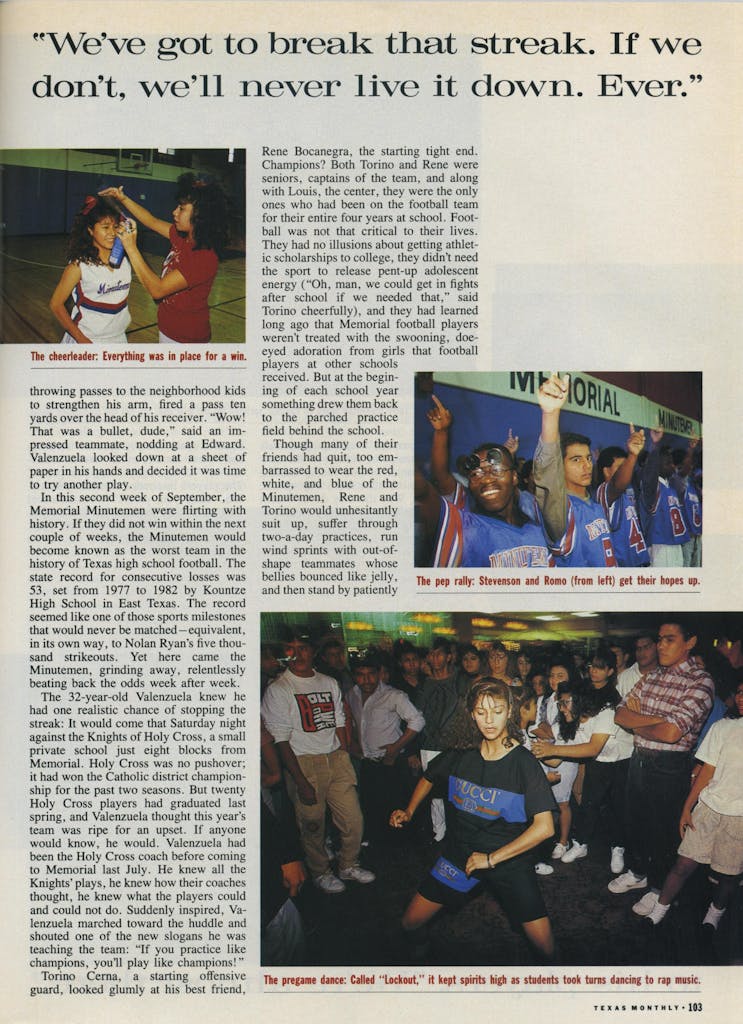

On Friday morning the entire school met in the gymnasium for the pep rally. Even though the two tuba players were a little late for the opening song, bursting through the double doors and ducking under the volleyball net to get to their places, the band gave an impressive rendition of the school song, a version of Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy.” Spray-painted banners hung on the walls: “Whip the Holy Cross Knights,” “Stomp the Knights,” “Unscrew the Knights.” Students screamed as the Minutemen filed out. The cheerleaders leapt about like a basketful of puppies. Then co-captain Torino Cerna approached the microphone to tell the students that this time—this time—the dream was going to come true.

“We’re going to win! ” Torino yelled, and the students cheered. “We’re finally going to do it!” he yelled louder, and the students cheered again. He took a deep breath, preparing for his big finish. “SEIZE THE DAY!” bellowed Torino, grinning like a madman. For a moment there was a perplexed silence as the students tried to figure out what he was talking about. Eventually—hesitantly—they cheered again. The football players were looking strangely at Torino out of the corners of their eyes.

At practice that afternoon the players were as tense as piano wire. They couldn’t seem to do anything right. Even running back Terry Stevenson, who rarely made mistakes, went the wrong way on a play and ran straight into beleaguered quarterback Edward Romo. “No problem,” Valenzuela yelled, clapping his hands for no particular reason. “Just keep concentrating.” Valenzuela thought of another of his slogans. “Practice like you’re playing,” he said. A few of the cheerleaders and pep squad members stood on the back steps of the school, watching the team. Half of the reserves turned from the field to stare back at them. “They are beautiful,” the boys whispered to one another, their eyes bright with hope and desire.

“Hey, you guys get up here and pay attention!” yelled Valenzuela. A layer of dust from the nearby road was swirled up by the wind and sent across the practice field. At that very moment it was difficult to imagine Memorial High School ever winning a football game again.

Meanwhile, less than a mile away, in uniforms identical to the ones worn by Notre Dame, the Holy Cross Knights were going through their final workout. Coach Angel Cedillo had told his team that the game would be Memorial’s Super Bowl. “They are smelling blood,” Cedillo said. “Do you want to be known as the team that Memorial finally beat?” The players, inspired, roared, “No!” and raced out onto the field to perform their drills with military precision. They ran up and down the field, their energy never flagging. Boys at Holy Cross are taught early to love football: Of the 325 students at the all-male school, 100 came out for the football program this year. “One thing to say about this year’s team,” said Cedillo, “is that they won’t be outhustled.”

Neither Rene nor Torino slept well that night. On Saturday morning, the day of the game, Torino woke up exhausted. He lay in bed underneath his girlie pictures and watched Inside the NFL on television. His parents, his relatives (three uncles, two aunts, and a five-year-old cousin who calls Torino Master of the Universe), and ten of his friends gathered in the front yard to decorate his home. They threw rolls of toilet paper through the trees, taped a Good Luck sign on the front door, and hung a mannequin dressed as a football player from the limb of a tree. “I can feel something different,” said Arturo Cerna, Torino’s father, an electrician.

Rene decided to spend the day decorating his blue Volkswagen. He strung crepe-paper streamers off the roof and stuffed crepe paper around the wheels. He painted “MHS War Wagon” on the back window, “Seniors 90” on one door, and “Seize the Day!” on the other. By midafternoon the usually calm Rene, after stopping at the Dairy Queen for his pregame hamburger, drove his little car over to Holy Cross and squealed through the parking lot, his head sticking out the window as he shouted, “Beat the Knights!”

By seven o’clock the sun was sinking in one direction and the moon rising in another. It was one of those lovely evenings of early autumn. The insects had left for the night, and a breeze snapped at the Stars and Stripes held by an ROTC student at the end of the field at Edgewood Stadium. The peace of the evening seemed to soothe the one thousand Memorial fans, a feeling that remained unbroken for several minutes until a strange piping sound emerged from the corner of the stadium. The Memorial High School band had decided to warm up with a scale.

For the 38 members of the Memorial Minutemen, all of whom had known only crushing defeat, their moment of drama, the grandest night of their young lives, had finally arrived. In the locker room, they nervously crossed and uncrossed their fingers. One player tapped his helmet against the floor, Edward Romo looked as if he was about to throw up, and the color had drained from Rene’s and Torino’s faces.

“Guys, all the hoopla is over,” said Oscar Valenzuela, his eyes unblinking behind his glasses. “There’s no more talk. Just us sitting in this room. No one can help us.” His voice remained calm. “We alone have to do it. We have to take it to them. It’s time for them to go down!”

A sound like a small explosion came from the locker room as the Minutemen clamored out the door and toward the field. They piled into one another on the sidelines, banging their helmets together, shouting, “Let’s go!” and “Chingatelo!” which, loosely translated, means “knock the hell out of them.” Near the field stood principal Joe Sanchez, his hands trembling. “I’m too nervous to watch,” he said. “These boys give it their all every week, and they come away with nothing. Oh, Lord, it just can’t happen again. I need a cigarette.”

Valenzuela figured that for the Minutemen to win they needed to score first and keep Holy Cross from building momentum. “They’re thinking they can lose,” he said. “If we hit them early, it might demoralize them.”

But the Knights, on offense first, quickly trotted up to the line, eager to move the ball. From the opening play, their running backs shredded through the line. Defensive players reeled away, their legs crumbling. “Come on, Torino! ” shouted one of Memorial’s assistant coaches. “You’re not tackling!” A Holy Cross runner, on an outside run, sidestepped linebacker Rene and nearly broke away for a touchdown before being dragged down. On the Memorial sideline there was that sinking, hollow feeling. Valenzuela consulted a clipboard, his lips pressed together like two hard pennies.

And then, on a Holy Cross pass play, Terry Stevenson intercepted on the 38 yard line. There was sudden hysteria. Coaches shouting instructions. The offense hurrying out. “Show them you’re winners!” cried Valenzuela.

A couple of plays later Terry fumbled, and Holy Cross recovered. Another round of hysteria. More coaches’ instructions. Then Holy Cross fumbled, and Memorial recovered. On and on it went, for the entire first quarter.

“Let’s get them! Let’s get them!” shouted Valenzuela.

Edward Romo rolled to the right, looking to complete his first pass. When four Holy Cross players came after him, he threw wildly downfield, directly into the hands of another Holy Cross player, who was so surprised that he dropped the ball. Valenzuela was apoplectic. He stalked down the sideline like Churchill through the bombed-out ruins of London. “Ed, eat the ball, eat the ball!” he yelled.

Cleats dug and ripped into the grass. Helmets collided. Forearms battered. Kids groaned. And then, with less than two minutes left in the first half, Holy Cross fumbled again on its own 11 yard line. There was a crazed scramble for the ball. A pileup. Curses. Referees. Whistles. Everyone motioning different ways to indicate who had the ball. The player who came up holding it high in the air was none other than Torino Cerna. His father leapt up in the stands and waved his hat. His mother’s arms were spread wide, as if she had seen a vision. Torino, perhaps for the first time in his life, held his forefinger up, shouting, “We’re number one! ”

Valenzuela called the bread-and-butter play: Terry Stevenson to the right. Edward Romo squatted behind center Louis Hernandez, barked signals, got the snap, and turned to make the pitch. It was . . . perfect! Terry took off for the end zone. One Holy Cross player was waiting, but here came, astonishingly, Ben Esparza, the trumpet player turned novice offensive tackle, his muscles surging as he bent low and made a textbook block.

“Holy shit!” said Oscar Valenzuela. For once, the great inspirational slogans had left him. Memorial led 7-0.

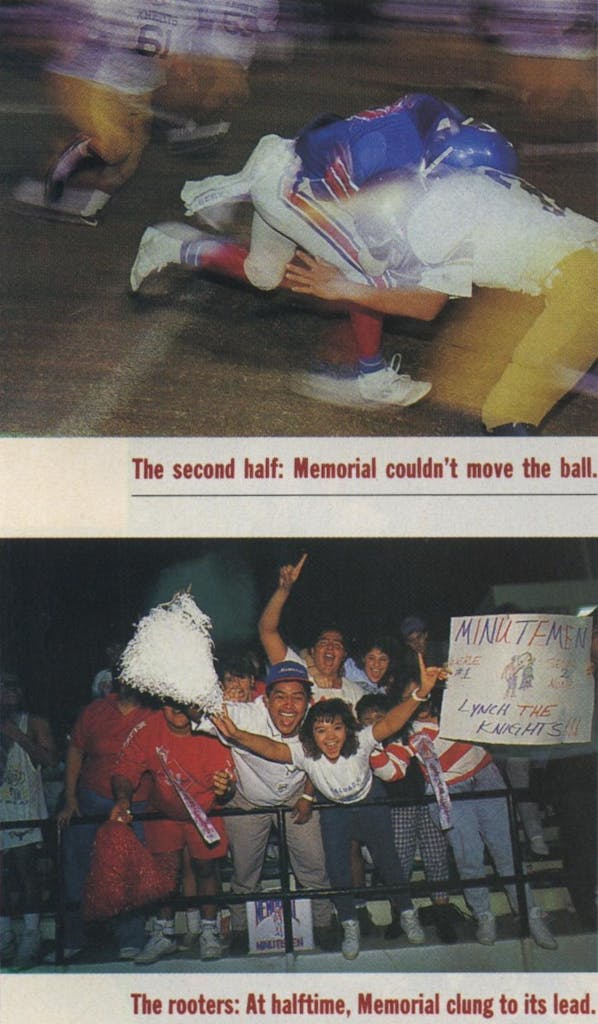

In the locker room at halftime, the players began to look at one another in a different way, realizing they were actually rattling the other team. Holy Cross seemed anxious: They had made four turnovers. “We’re bad!” said Torino, which, of course meant that he and his teammates were looking good. Meanwhile, out on the field, the Memorial band had lined up to play “Tequila Mockingbird.” When it was over, the musicians looked at one another in a dazed, wondrous way, the applause from the crowd washing over them. They couldn’t believe it—the music had sounded beautiful. Principal Joe Sanchez, now sitting high up in the stands, shook his head and said, “Something amazing is happening here.” But not all the fans were as hopeful, for they had sat through many second halves in which the Minutemen, exhausted and outmanned, completely fell apart.

Almost immediately in the second half, Holy Cross barreled back at Memorial. The offensive line burst forward with a stunning whack of helmets; the running backs dashed through openings. Inexorably, Holy Cross was inching its way to the goal line.

Yet the boys of Memorial unflinchingly came straight in to meet them. Although a college scout in the bleachers might have euphemistically described the play as “spotty,” on the field the rush of converging bodies was frightening. Torino loomed over the line like a colossus, flinging out his arms, screaming something in Spanish. Rene, playing linebacker, threw his 155- pound body at players who were twice his size. Middle linebacker, Eugene Salazar, tackling with bull-like rage, single-handedly dragged down a runner on fourth down, giving Memorial the ball. His parents, huddled together near the top of the stadium, their bodies still weak from the cancer, slowly rose with the rest of the fans to cheer, the noise so loud that the players could barely hear Valenzuela’s instructions.

Memorial’s offense, however, was sputtering. Though Edward twice completed short passes to Rene, the Holy Cross defense was concentrating on Terry. If he could be shut down, the Memorial offense would go down as well. Every time Terry got the ball, a swarm of tacklers smothered him. “It’s up to the defense,” Valenzuela said as the offensive players staggered off the field, gasping for air, their chests heaving with each breath. Valenzuela couldn’t help himself. “Keep your poise!” he yelled. “We’re almost there!”

The game entered the fourth quarter. The moon was so bright that the nearby neighborhood looked almost beautiful. Back came Holy Cross, its runners bucking for more and more yards. The caged faces of the players steamed from the heat, the tackles became more desperate, and Valenzuela’s voice grew hoarser. On one formation a Holy Cross receiver lined up wide to the right, and suddenly Valenzuela was going crazy. It was a play he remembered from his own years there. “Reverse! ” he screamed. “Watch the reverse! ”

But no one seemed to hear him. The reverse worked exactly as it was diagrammed—the receiver raced behind the quarterback and took the handoff. An empty field stretched out before him. Valenzuela stepped backward as if he had been shot. It was all over. The entire defense had been fooled. The runner turned upfield, the end zone loomed ahead—and then Valenzuela saw a flash. Terry Stevenson, who was playing defensive back, later would not be able to say how he had moved so fast. “I don’t know,” he would say. “I just found myself there.” But he headed after the runner, moving like a ghost, trying to make up the impossible distance. After a chase that seemed to go on for minutes, Terry flung himself savagely on the leg of the runner, hoping to trip him. The runner fell, and the ball slipped loose. Memorial recovered. The game was saved.

Oscar Valenzuela stood at the 50 yard line, curiously alone amid the commotion, his eyes flickering as if he could not believe what he was seeing. The clock ticked down. With less than a minute to go, an assistant coach came up to Valenzuela, put an arm around him, and said softly, “There ain’t no more streak, Coach.”

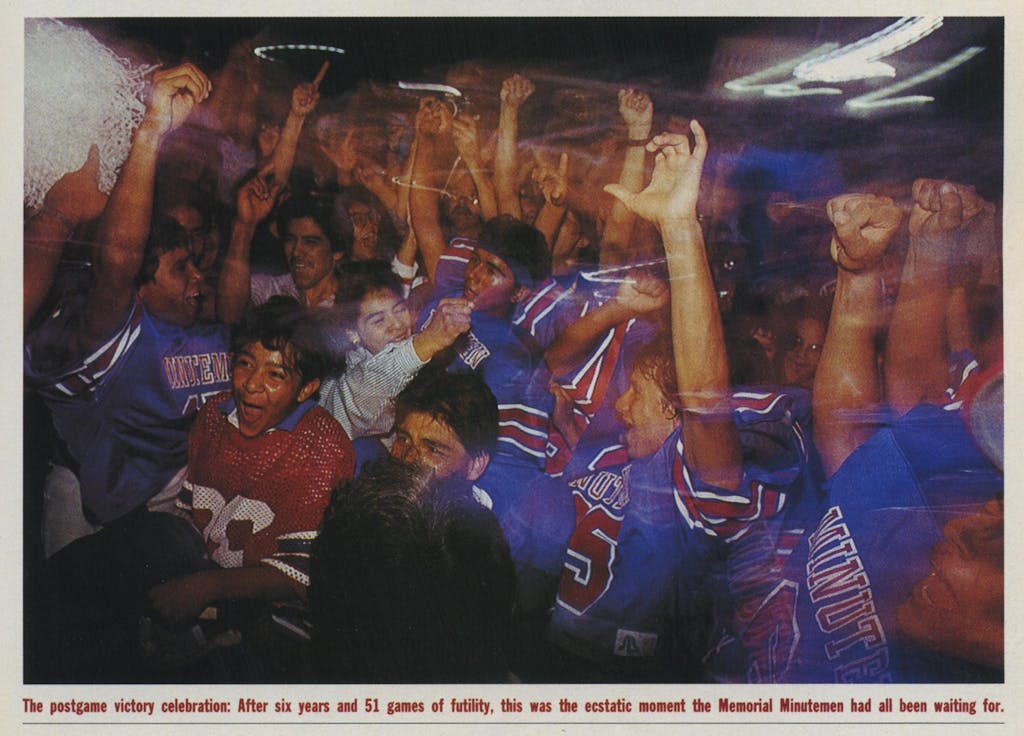

Then came the final horn, and the people poured out of the stands, the students and the parents and the teachers and even principal Joe Sanchez, wiping tears from his eyes. There was Torino’s father, his face red with joy, and there was Albert, shouting, “I can’t believe it! I can’t believe it!” They all came running across the field, a great roiling whirlpool, grabbing and tearing at the players out of sheer love. Torino, of course, was out of control, happily tackling his own teammates. Edward Romo had whipped off his helmet and was combing his hair, apparently for any nearby photographers. A couple of players, trying to douse Valenzuela with a cooler of water, missed, hitting an assistant coach instead. In the stands, the Salazars, both of whom had outlived doctors’ projections, stepped down to the railing to wave softly at their son.

And just as he had predicted, Rene Bocanegra seemed uncertain how to respond to the passion of the moment. Even as some boys lifted him onto their shoulders to parade him around the field, his face shifted from glee to a sort of poignance and then back again. Finally, when a reporter asked him the inevitable postgame question—“How do you feel?”—Rene looked for a moment at his hands, tried to keep his voice from shaking, and then said, “We finally won, sir.” For all of these people, that night was a gift, one hammered out of endurance and dedication and certainly a little luck. In the end, perhaps, the game would change nothing but that one night—and that, at least, was something, the chance to find some joy and have it carry over into tomorrow.