This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

A chilling January wind is blowing off the Potomac as the fortieth president of the United States finishes his inaugural address. Behind Walter Mondale on the platform, dignitaries hunch into their overcoats, but here and there enough of a face remains visible for a television commentator to identify it. The man applauding politely is Lloyd Bentsen, the new vice president, falling into the subservient role he must play for the next four years. The tall man staring through small circular glasses, looking like the consummate Washington pro, is Jim Johnson, Mondale’s campaign chairman, who will succeed James Baker as White House chief of staff. And the young, athletic-looking one with the thick blond hair? The commentator searches his memory. Ah, yes. That is Roy Spence, the 36-year-old adman who came out of Texas to mastermind the TV blitz that carried Mondale past Ronald Reagan in the campaign’s final days.

So much for fancy; now for fact. With Inauguration Day a year away, Walter Mondale is not the betting favorite to be the next president of the United States. He is merely the Democratic front-runner, a perilous position that makes him a prime candidate for a New England Life advertisement. Even if he wins the nomination, he will be a decided underdog against a popular president. Lloyd Bentsen’s chances are even more problematic. But Roy Spence’s future is secure—win or lose. When he won the job as Walter Mondale’s media adviser last spring, he automatically joined the Democratic establishment, state and national. He is positioned to become a power in Texas politics for years, even decades. That’s no small feat for someone who has yet to handle even one successful statewide campaign from start to finish.

How did Roy Spence catch Mondale’s eye? Why did he get the job? What does he plan to do with it? The answers to those questions explain a lot not only about the Mondale campaign but also about Texas politics. A dozen years ago Spence, just out of UT and still wearing his hair in a ponytail, ventured into politics for the first time. His client: Ralph Yarborough, beloved of the old-line liberals, bane of the John Connally conservatives, who was making a futile bid to return to the U.S. Senate. The effort that earned Spence his national reputation, though, was his work for Mark White in the closing weeks of the 1982 governor’s race. The journey from Yarborough’s race to White’s—from ideological division to relative unity—was the same path taken by the Texas Democratic party as Texas became a two-party state. And nothing so clearly explains the imperatives of modern politics as the fact that the person who most symbolizes this transformation is Roy Spence, not a politician but a consultant.

Roy Spence’s chosen profession does not rank high among America’s most admired occupations. The books critical of political consultants would fill a shelf. The first was The Selling of the President 1968, Joe McGinniss’ detailed account of how Richard Nixon’s admen sold the notion that there was a “new” Nixon. The most recent work in this lineage is The Permanent Campaign, by Sidney Blumenthal, who states his thesis in the first sentence: “Political consultants are the new power within the American political system.”

Reading these books is a lot like reading about genetic experimentation. As much as the authors admire the technique, they never let you forget how dangerous to society they believe it to be. Out of this literature emerges a gospel: television has replaced the political machine; the consultants are the new bosses; they are hired guns who have technical skills, but unlike the old bosses, they respect no loyalties, deliver no votes, provide no public services, and enforce no discipline; they deal in images rather than realities; they have permanently transformed American politics—for the worse.

Just how important are these guys, really? Talk to enough pols and pros and you will find that three theories emerge:

(1) The Bum Phillips theory of media omnipotence. Remember when Phillips coached the Houston Oilers? The Oilers were good, and the New Orleans Saints were hopeless. Now Phillips coaches the Saints, and it is the Saints who are good, the Oilers who are hopeless. The lesson is that the coach is more important than the players or, to return to politics, that the consultant is more important than the candidate. Under the Bum Phillips theory, anybody can be elected to high public office—provided he can afford the right media man. Example: the 1978 Florida governor’s race, when Bob Squier started the campaign with zero per cent of the vote and zero name identification and won the race. By the way, the candidate’s name was Bob Graham; Squier, based in Washington, is one of the leading Democratic media consultants. Squier will have another opportunity to test the Bum Phillips theory in Texas this spring. He is handling Kent Hance’s campaign for the U.S. Senate, and Hance is starting out about where Graham did.

(2) The arms race theory of media escalation. Modern campaigns are like the nuclear buildup: candidates deploy more and more weapons (there are specialists not only for advertising but also for polling, mailing, and telephoning), technological superiority is fleeting, and the cost keeps going up all the time. Consultants are important, but only to neutralize the other side’s consultants. Example: the 1982 Texas governor’s race. Back in the seventies a candidate could get the jump on an opponent, just as Bill Clements used polls and phone banks to sneak up on an overconfident John Hill in 1978. By 1982, however, Mark White knew enough to match Clements consultant for consultant.

(3) The sow’s ear theory, as in, you can’t make a silk purse out of the wrong candidate or the wrong year. Example: Jim Collins against Lloyd Bentsen. Or the 1981 San Antonio mayor’s race between rising star Henry Cisneros and the old guard’s John Steen. Steen hired John Deardourff, one of Washington’s glamour consultants, but to no avail: the election was the crest of a 250-year tide, in which Deardourff was no more than a droplet, leading to the election of the city’s first Mexican American mayor.

Which theory is right? They all are; it depends on the race. Free of constraints, a consultant can work miracles—but there are always constraints. Money is one: TV, an expensive buy, favors the rich. Exposure is another: television is a superb tool for gaining name recognition and establishing an image, as Bill Clements did in 1978. It is less useful when a candidate already has name recognition and an established image, as Bill Clements did in 1982. There are so many variables that a consultant’s judgment and instinct are as important as technological mastery. Political consulting is really three professions in one—film, sales, and politics, possibly the three most fickle professions on earth—and the best media campaigns work on all three levels. Just as with movie directors, there are enormous differences in quality, not only between consultants but also within each consultant’s work. That is why, despite all the hullabaloo about the power of media men, the essence of politics will always be more art than science.

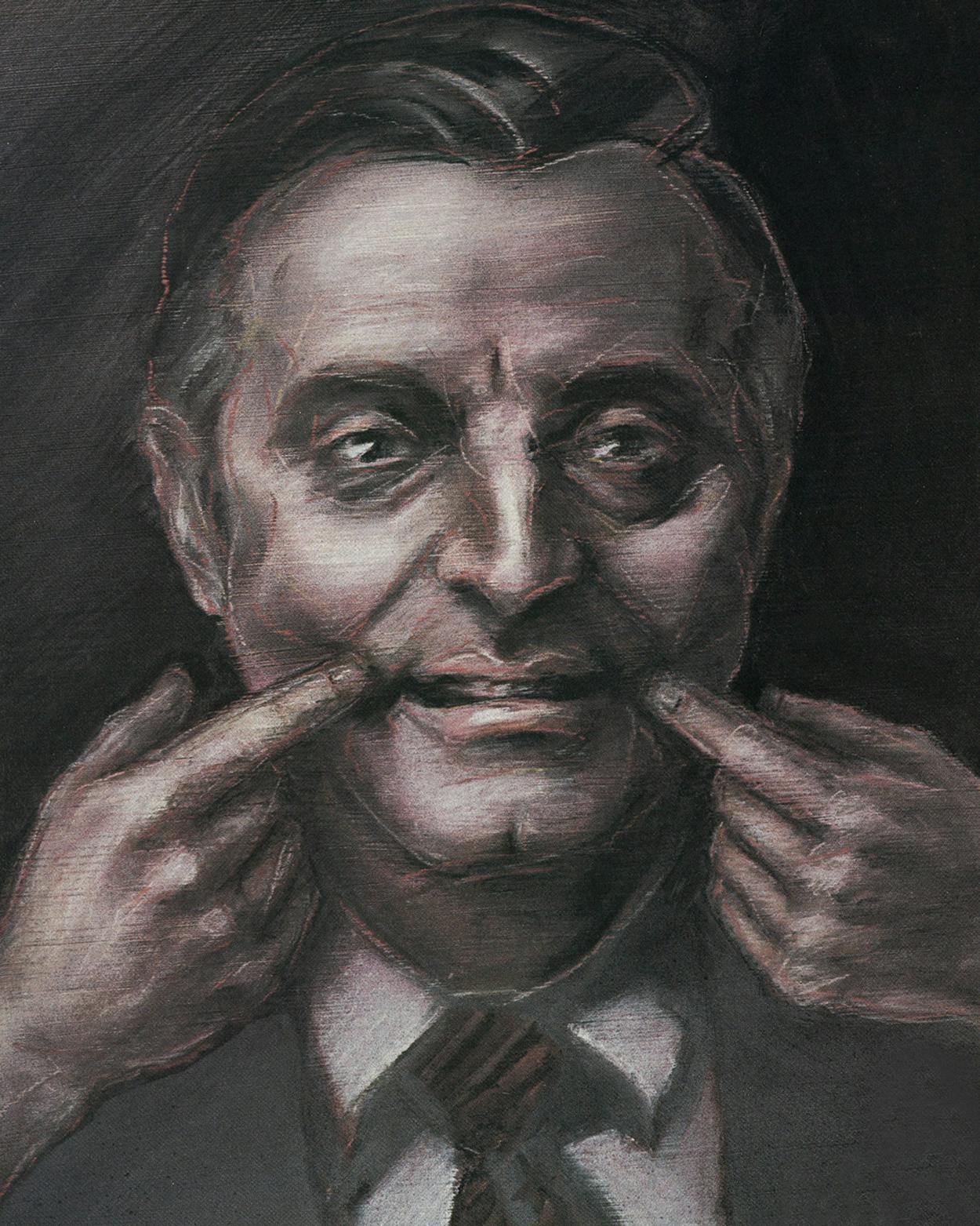

Walter Mondale is not a product of the media age. A preacher’s son, he has a style that on camera ranges from pious to stuffy. Mondale was first elected to the U.S. Senate in 1966, before the era of modern media politics. Mondale doesn’t like TV campaigning—it was one of the reasons he balked at the starting gate of the 1976 presidential race—and he particularly doesn’t like media consultants.

One afternoon in January 1983 his dislike was showing. He was in his suite at the Adolphus Hotel in Dallas and had just found out that his next visitor, someone named Roy Spence, was a media man. The trouble was, a few days earlier Mondale had had a miserable meeting with a consultant from California, who had been full of jargon and ways for Mondale to change his image. Afterward, Mondale gave orders that he didn’t want to meet with any more media consultants for a while. When he found out about Spence, he was furious, but he agreed to go ahead with the meeting. Spence walked into the room and said, “I understand that you don’t like media people worth a damn.”

Spence and Mondale went on to talk for 45 minutes. They talked substance —how the defense issue might be turned against Reagan by showing how unbusinesslike defense spending has become. And they talked philosophy—Spence’s philosophy of running campaigns. Spence is not a disciple of the Bum Phillips theory that the consultant is more important than the candidate. “That’s bullshit,” he told me during the Christmas campaign lull this winter. “I really try to tap into the truth about a candidate. The truth sells. It has an aura around it that people can see. It pops.“ Spence talks in cadences that are almost Germanic—his sentences end in verbs, reserving the punch for last. “Voters don’t have to believe everything a candidate believes, but they have to believe that he believes.”

Spence had been well briefed for the Mondale visit. The appointment had been set up by Bob Beckel, Mondale’s campaign manager. Beckel and Spence had become friends in 1980, when Beckel came to Texas with the hapless assignment of running Jimmy Carter’s reelection campaign. Later, Beckel stayed in Austin to do some consulting; he handled the reelection of Austin mayor Carole McClellan in 1981, turning often to Spence for counsel. Beckel, whose role in the Mondale campaign is not as grandiose as his title, was a little reluctant to push a national novice, but under prodding from mutual friends in Austin, he arranged the meeting. Spence, a salesman first and a consultant second, did the rest.

Roy Spence has always been a salesman. He was a high school quarterback, a salesman’s position if ever there was one, on a state championship team in Brownwood. At UT in the late sixties, he was an antiwar activist but not a dropout or a flower child. In his spare time he and some friends picked up money by putting on mixed-media events, like light shows for fraternity parties and slide shows for trade associations gathering in Austin. Upon graduation they decided to stay in Austin and start an advertising agency. Spence became the one who made the sales pitch to prospective clients.

The company, now known as Gurasich, Spence, Darilek & McClure, or GSD&M, began life with the accounts of two local retailers. Today GSD&M has branch offices in Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio and a subsidiary for developing real estate. Its annual billings exceed $50 million. Its clients include Southwest Airlines, Coors, and a pizza chain that was the agency’s first big success story. Asked by a client to distinguish his shops from the Pizza Inns and the Pizza Huts, GSD&M ran combinations of Italian-sounding syllables through a computer and came up with Mr. Gatti’s.

Because the founders flouted the established guidelines for reaching the big leagues of Texas advertising—they chose youth over experience, Austin over Dallas, the political left over the right—they were often an object of derision in advertising circles. What the initials GSD&M really represented, competitors said, was Greed, Sex, Drugs, and Money. Roy Spence used the line himself. “They say that’s what we stand for,” the salesman would tell potential clients. “Now let me tell you what we really stand for.”

Politics has never been a big moneymaker for GSD&M. But politics has helped the firm prosper in less direct ways. In 1974, for example, Spence handled the advertising in Bob Krueger’s first congressional campaign. The leading fundraiser, previously unknown to Spence, was L. D. Brinkman, the world’s largest floor-covering dealer. Years later Brinkman bought Mr. Gatti’s in a deal GSD&M helped swing; he remains a major commercial client today. One can safely assume that it would not hurt GSD&M’s commercial business to help elect the next president.

The agency’s first venture into politics, the 1972 Yarborough race, was a disaster. Spence got the contract mainly because the established firms wanted no part of Yarborough and other possible competitors were scared away by the former senator’s inability to raise money. Spence ended up borrowing money personally to pay for media spots, but he was left holding the bag when Yarborough lost the primary to Barefoot Sanders. For several years afterward Spence helped organize fundraising dinners for Yarborough until he and other creditors were paid.

In 1973 his luck changed. The state Senate seat from Austin opened up with the resignation of the incumbent. Spence handled Lloyd Doggett’s advertising in a successful campaign that turned out to be a minor technological watershed. Texas media politics still wasn’t very sophisticated in 1973. The only two memorable campaigns had been aimed at Ralph Yarborough, by Lloyd Bentsen in 1970 and by Allan Shivers in the bitter 1954 governor’s race. Shivers ran a devastating antiunion TV spot displaying the deserted, trashed-out streets of downtown Port Arthur as evidence of what would happen if Yarborough were elected governor. (What the spot did not say was that the scene had been shot at dawn on a Sunday morning.) In the Doggett race Spence did something that was less dramatic but totally new. He prepared different radio spots for each local station, targeting the message to the particular audience, instead of the usual single spot distributed to all stations. The technique is common today, but Spence is credited with being the first to use targeting in Texas.

That same year Bob Krueger, an English professor at Duke University, decided to come back to Texas and run for Congress from his family’s hometown of New Braunfels. He called a political science professor at UT for advice; his friend recommended that he talk to a smart young fellow named Roy Spence. Krueger hardly seemed suited to the huge district, larger than Pennsylvania, that sprawled from northwest San Antonio to the Trans-Pecos, and Spence spent much of their first meeting trying to persuade the candidate to move to Austin, a district more likely to elect a university professor. Krueger resisted, staying home to enter a six-man race in which two of his opponents were better-known political veterans. But 1974 was the height of the Watergate furor, and the voters were receptive to outsiders.

Just before the election, Spence produced a coup. A San Antonio newspaper picked the ten most powerful men in town. All ten supported one of Krueger’s opponents, a San Antonio state senator. Spence, displaying for the first time a trait that one day would intrigue Walter Mondale and Jim Johnson, turned the news to his advantage. He swiftly put out a tabloid that trumpeted, “If you believe that ten politically powerful men in San Antonio should have the power to handpick your next congressman, don’t read the following pages.” Spence had discerned what few Texans understood in 1974: the real division in Texas politics was no longer liberal-conservative but urban-rural. The sheep and goat ranchers voted against the city power brokers and for the scholar with the curly hair. So did the antiestablishment sector of the San Antonio electorate. Krueger won.

By the mid-seventies, GSD&M’s commercial business was booming and Spence had less time for politics. His next big campaign, Krueger’s 1978 race against John Tower, was one that belied the power of media consultants: Krueger started close, stayed close, and finished close, and nothing Spence came up with, including a dramatic TV spot of Tower’s signature vanishing, altered the numbers. In 1980, a Republican year, Spence handled Jim Wright’s reelection to Congress from Fort Worth. That race later impressed the Mondale people, because the House majority leader, too heavy of eyebrow and oratory, comes across even worse on TV than Mondale does.

The big one, though, was the 1982 governor’s race. Spence came in late, taking over Mark White’s radio with three months to go and his TV a month later. The Republicans outspent the Democrats two to one, but the Democrats generated a huge turnout of new voters. The Democratic candidate used television to get across his message that the Republican incumbent didn’t care about ordinary people. The Democrat won a race that the experts said couldn’t be won. When Jim Johnson examined the Mark White–Bill Clements race the following spring, he saw something familiar. It was very much the scenario he envisioned for Walter Mondale against Ronald Reagan.

Among the books and papers on Jim Johnson’s desk is an unusual fixture—a large bottle of aspirin. As the boss of the Mondale campaign, he has had many headaches in the past year. One of the biggest was choosing a media consultant.

Johnson had barely heard of Roy Spence when Mondale himself called after the Dallas meeting. “I met a guy you’re really going to like,” Mondale said. Johnson knew what that meant: Mondale had met a guy he really liked. Still, given Mondale’s opinion of media men, that was saying something.

Johnson had in his mind a picture of the ideal consultant for Mondale. Most of all, he had to get along with the candidate; that hurdle was already cleared. As Johnson began checking out Spence with Texans friendly to Mondale, like Jack Martin, Lloyd Bentsen’s 1982 campaign manager, and Buddy Temple, erstwhile candidate for governor and an early Mondale backer, Johnson began to think he might have found his man.

He wanted someone who emphasized, in his words, “real issues.” Johnson learned how Spence had used utilities against Bill Clements. (Never mind that the utility issue was more phony than real.) Johnson wanted a consultant who could react quickly to events. He learned that Spence had stayed up all night after a Clements-White debate to produce spots blasting Clements for supporting a gasoline tax increase. Johnson wanted one major campaign post to go to an outsider—the Mondale organization was top-heavy with old Washington hands, from Johnson himself to Beckel and pollster Peter Hart. Thus Spence’s lack of national experience was no barrier. Finally, Johnson wanted someone who would be an asset in an important state. Texas is essential for Mondale; no Democrat has ever been elected president without carrying it. Spence had roots into the entire Democratic field; he transcended the old days when the party was deeply divided. His clients ranged from state treasurer Ann Richards on the left to Bob Krueger in the center to Mark White on the Dolph Briscoe right.

One thing remained to be done: the Mondale team had to review the reel of Roy Spence’s work. To a political pro, TV spots might as well carry the consultant’s signature; his fingerprints are all over the screen. The Mondale pros were looking for Roy Spence’s signature. They saw Bob Krueger, normally a starched and formal man, wandering past a gazebo wearing an outdoor jacket and a blue shirt open at the neck. They saw Mark White in jeans and a work shirt, lambasting Bill Clements for listening to Wall Street instead of Main Street. They saw Jim Wright standing before a classroom of schoolchildren, leaning forward and saying, “Yes, Lisa, I believe in school prayer.” They saw Garry Mauro, more a backroom operator than a media candidate, walking coatless over sand dunes by the Gulf of Mexico.

Three things about Spence’s work stood out. First, it was casual. He had taken a bunch of TV corpses and made them seem like just plain folks. Maybe he could do the same for Walter Mondale. Second, it was tough. Spence’s negative spots against Tower and Clements are regional classics, such that they have even acquired titles in Texas political circles—“The Disappearing-Signature Spot,” “The Caviar Spot.” They exploit the fatal weakness of an opponent in the mind of the viewer; George Shipley, Texas’ leading pollster, calls them “ice picks to the brain.” Third, it was good film. In his best spots Spence used props to create drama before the viewer knew he was watching a political ad: an opulent cocktail party to portray the type of people who support Bill Clements; a quill pen and a green eyeshade to indicate the backwardness of the state treasurer’s office. The Mondale people liked what they saw. By June the deal was struck. Roy Spence’s job description with the Mondale campaign? Reduced to a single phrase, it was to get Walter Mondale to loosen up on television.

Walter Mondale’s media consultant is not the all-powerful political boss of The Permanent Campaign. That says less about Spence than it does about Jim Johnson. The inner circle of the Mondale campaign is more like a dot: Johnson is both strategist and boss. The success of Johnson’s 1983 strategy—circle the bases of the Democratic pressure groups, scoring endorsements from labor, teachers, women, and blacks—has vindicated his one-man rule. So has the deterioration of Mondale’s leading opponent, John Glenn, whose campaign has been plagued by infighting at the top. Between September and December Mondale stretched his lead over Glenn in Time’s poll fourteen points, from 26–24 to 34–18. Unless Glenn reverses his fortunes in the initial skirmishing—the Iowa caucuses and the New Hampshire primary in late February and the Southern primaries on Super Tuesday, March 13—he could be knocked out in round one.

That would suit Roy Spence just fine. He confesses to being “behind the learning curve” for a presidential race. Austin friends describe him as uncomfortable with the serial nature of the nominating process, where climactic battles are fought, then forgotten, as new fronts are opened up. A head-to-head confrontation between Mondale and Reagan is much more Spence’s style.

The media strategy for the nomination, Spence says, is to move gradually from personality to issues. “First a voter has to know the person,” he says. “Then he has to know his values. Then he has to know where his values will take the country.” Spence does not intend to let Mondale repeat Jimmy Carter’s mistake in 1976, when Carter almost lost big leads for both the nomination and the election: Carter never got into specifics, and as the campaign dragged on, voters began to have second thoughts—for good reason.

The strategy has already started. Ads currently running in Iowa and Boston show Mondale talking about trade, rebuilding America, and the economy. Other spots in that series, already shot but not yet aired, deal with jobs, defense, and—a Spence hardy perennial—utilities. The spots reflect Spence’s uneasiness about the nomination campaign; they are not his best work. They use head shots of Mondale—no props, no drama—and the militant rhetoric doesn’t quite ring true: “I am not a sucker.” . . . “We want to get tough again. We want to be first again.” . . . “They must know we’re not going to be pushed around.” . . . “Agreements with the Soviet Union are not based on trust.” . . . “When we stand up for arms control, we’re not weaker, we’re stronger.” Only the utility spot, inspired by the AT&T breakup, rises above the prosaic. Mondale’s criticism of high bills is interrupted after each sentence by cutaways to just plain folks complaining about burdens on the middle class.

In getting Walter Mondale to loosen up, though, Roy Spence has had more success. On December 10, 1983, Walter Mondale’s presidential campaign went public in a five-minute program that was shown nationwide. It opens with a shot of a cork bobbing on a fishing line, then switches to a hand on a casting reel. The viewer, hooked, hears Mondale’s voice before he sees his face. “I’m sort of a farm kid. I worked on a farm. I love the out-of-doors”—now Mondale is walking by a white fence in a sylvan setting—“I love to fish, and I get a lot of strength out of it.” Mondale is wearing a brown checkered sport shirt with a brown pullover sweater. At the neck, his T-shirt is showing. He looks like a Roy Spence candidate, folksy and loose. Really loose: Mondale moves, onto a tennis court, whacks at a ball, and starts chasing the return. He misses. “Yes, that shot was in,” he shouts to an unseen opponent, “and you’re fired.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Austin