This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Frania Tye Lee would never forget the way H. L. Hunt bought her off. It was in January, she told the court, back in 1942. The two of them were in Dallas, at the Hotel Adolphus, momentarily alone. All of a sudden, Hunt closed the doors to their adjoining rooms. He shut the transoms and checked the outside hall. Then, satisfied that no one else could hear, he offered her a million dollars to sign a statement saying that he had never really married her.

“That’s when I became very angry and screamed that I would never sell my children for all the money he had,” Mrs. Lee recalled.

Why, asked Mrs. Lee’s attorney, did H. L. Hunt want you to deny that you were married to him?

“So that he would not be revealed as a bigamist,” she replied.

Whether or not she was telling the truth, Frania Tye Lee made an excellent witness. Appropriately described by her attorney as “a well-preserved seventy-three,” she held her gray head high and spoke of her calamitous experiences with H. L. Hunt as calmly as if she were reporting the details of a routine family dinner. She had put on too much make-up, especially powder, and the stark courtroom light made her face look waxen and unnaturally white. But she still had the enormous blue eyes, the very wide and handsome jaw, and the outlines of the sturdy, full-breasted figure that had attracted the young Hunt in the twenties. The flaws of her old age and her attempts to hide them only made her seem more sympathetic, more victimized.

Frania Tye Lee had come back to claim her share of the Hunt empire after more than half a century of living lies, and now, three days into the trial of her lawsuit, her chances were looking better and better.

Across the crowded Shreveport courtroom, the so-called “first” and “second” families of H. L. Hunt were therefore looking bleaker and bleaker. For them, Mrs. Lee’s lawsuit was the latest unpleasant chapter in the continuing saga of their late father and the living legacy of his three feuding families. The children of H. L.’s first wife, Lyda, and those of his mistress (and ultimately, second wife), Ruth, were accustomed to fighting among themselves. The enmity between them was not, as often portrayed, an all-out war. One did not try to plot the destruction of the other. Rather, the two factions engaged in a constant opposition of philosophies and styles, a sort of running disagreement—about everything. In fact, just prior to their arrival in Shreveport, the first and second families had been quarreling over their greatest source of discord: how to manage the remnants of their father’s vast estate. They had reunited only to face the threat now posed by Mrs. Lee and her “third” family.

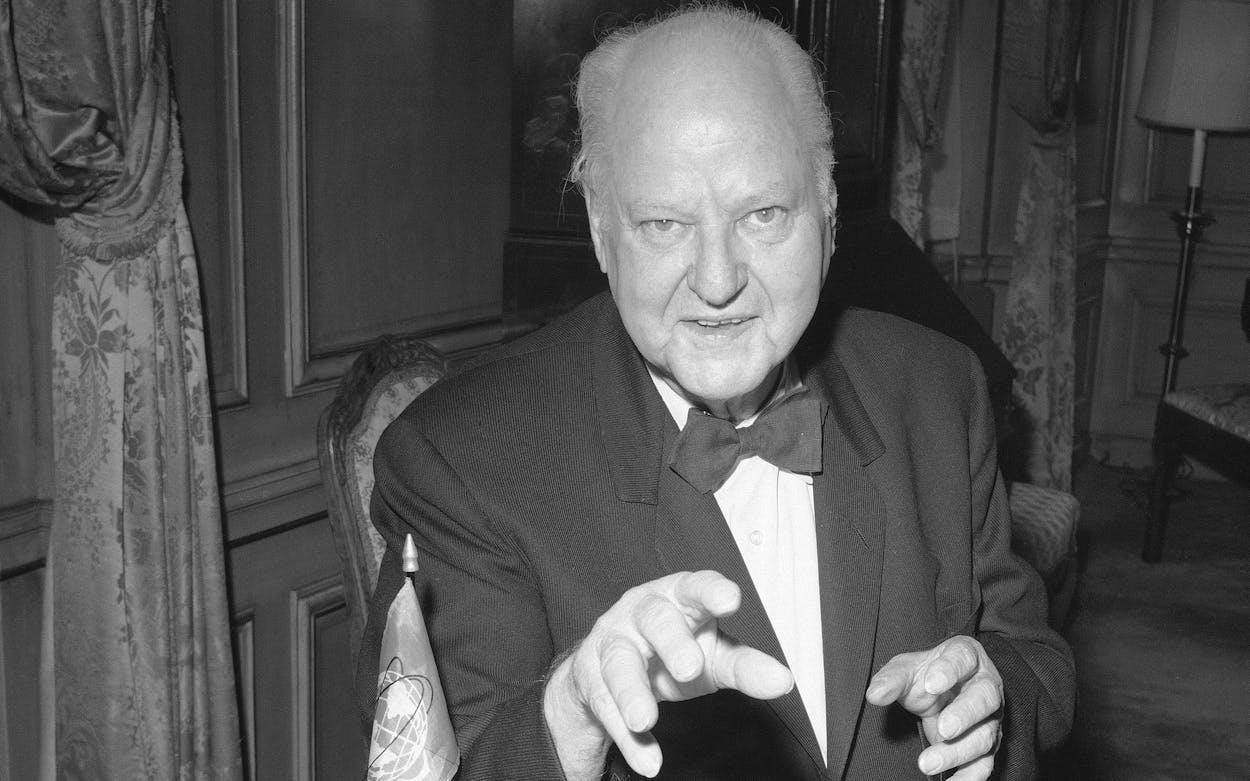

With wives and children occasionally swelling their ranks to over a dozen, the Hunts made a very impressive show of solidarity. Even so, it was not hard to tell them apart. Ray, the oldest child of the second family and the named defendant in Mrs. Lee’s lawsuit, sat at the counsel’s table with his back to the audience, his hands neatly folded in front of him. Blond, broad-shouldered, and fastidiously clean-cut, he bore a remarkable resemblance to his old man: the same jaw, the same puffy cheeks, the same intense eyes. At 34, he was also just about the same age H. L. had been when he first encountered Frania Tye. Earlier in the week, testifying in his capacity as sole executor of his father’s estate, Ray had acknowledged that his father was also the father of Frania’s four children. Then he had returned to his seat to await the defense’s turn to argue.

The other Hunts observed the proceedings from a special section of seats to the right of the defense table, directly across the room from the jury box. Ray’s younger sisters sat at the far end: June, the strawberry-blonde who went by the nickname Peaches; Swanee, the youngest, a chubby blonde; and Helen, the middle one, a slim brunette with more angular features than the others. A Hunt Oil Company aide sat on one side of the sisters; Ray’s blonde wife, Nancy, sat on the other. With their soft and innocent complexions, the four Hunt women of the second family looked like a row of inquisitive angels.

The children of the first family did not look at all angelic. A half-generation older than Ray and his sisters, they all had dark hair and less uniform though still unmistakable variations of their father’s features. They were also more expressive. Bunker, age 52, the oldest active son, showed his feelings most. Slouching back in his chair with his tiny hands folded over the great swell of his prodigious belly, his glasses jammed against his forehead by a sullen frown, the stayless points of his shirt collar bent forward on each side of his tie like tiny white horns, he resembled a spectacled dinosaur caught in a primeval mud bog and brooding over it. Virtually nothing about him hinted that he had once been the world’s richest human being.

Bunker’s sister Caroline sat to his right with her graying hair pulled back in a bun, her arms folded, her face wrinkled in a frown approximately half as intense as her brother’s. Herbert Hunt, correct and businesslike as always, sat beside his blonde wife, also named Nancy, pensively resting his hand on his cheek. Lamar, age 45, the youngest, fidgeted most. Crossing and uncrossing his legs, he would lean forward, remove a gold ball-point pen from the inside pocket of his habitual blue blazer, examine the ends of the pen as if it had mysteriously arrived from another planet, then replace it.

Three more in-laws completed the family portrait: sister Margaret’s tennis-playing husband, Al Hill; Caroline’s husband, Buddy Schoellkopf; and Lamar’s attractive wife, Norma. A slim, vivacious woman with exquisitely delicate features and big brown eyes, Norma was easily the most stylish and the most striking of the Hunts, male or female. The sole incongruity was her hair—a great pile of thick blonde hairpieces that diminished rather than increased the shine of her considerable natural beauty.

The only regular family members not present in the courtroom were absent for good reason. H. L. H. III, the emotionally disturbed, oldest first family son known as Hassie, had not come because his illness has prevented him from appearing in public for over 25 years. Margaret, his steel-willed oldest sister, a potential witness for the defense, had chosen to remain in the hotel rather than suffer the indignity of waiting outside the courtroom with the other witnesses. Meanwhile, Ruth, the mother of the second family, had stayed in Dallas on the advice of the attorneys, who feared that if she made the trip to Shreveport, the other side might call her to the witness stand and try to embarrass her with the fact that her own children—Ray, June, Swanee, and Helen—had been born out of wedlock before the death of H. L.’s first wife, Lyda.

Frania Tye Lee’s testimony provided embarrassment enough. Claiming that Hunt had introduced himself to her as “Major Franklin Hunt,” she said that she had lived with him for nine years before discovering his true identity and the existence of his other wife and family. She went on to admit that after the scenes in the Hotel Adolphus, she did sign a statement denying her marriage to Hunt, as well as a document releasing him and his estate from any further claims. She also admitted accepting nearly a million dollars in the form of cash, trust funds for her children, and monthly payments of $2000, which she continued to receive right through the day of her testimony. However, she said she capitulated only because of Hunt’s pressure, his complaints of indebtedness, his assertion that the court records of their marriage had been destroyed, and, most of all, his promise to recognize her and her children on an equal basis with his first family when he wrote his will.

Mrs. Lee said she had let the matter rest until 1973, when Hunt published his autobiographical family history, Hunt Heritage. The book, she said, had upset her terribly because it did not even mention her or her children. Two years later, when Hunt’s will was opened, she discovered that H. L. had left four-fourteenths of some Louisiana oil properties to the “Reliance Trusts” he had set up for her children. However, like Hunt Heritage, the will failed to mention her or her children by name. That, she said, was why she had decided to file suit against the estate. She told the court that shortly after her decision to sue, her son, Hugh Lee Hunt, accompanied her to Florida to look for a marriage license. Although she had looked twice before without finding anything, this time they discovered a voided entry in an old record book that appeared to support her claim.

Now Mrs. Lee was asking the court to declare her Hunt’s “putative” (commonly accepted) wife. She was also asking for one-half of all the community property H. L. had accumulated between 1925, the year of their alleged marriage, and 1934, the year she claimed to have discovered his true identity, plus all the subsequent fruits of that community property. In a separate but related lawsuit filed in a Baton Rouge court, Mrs. Lee’s children were asking to be declared H. L.’s legitimate heirs.

As Ray Hunt conceded at the following recess, this was “not your run-of-the-mill trial.” The main reason, of course, was because the Hunts are not a run-of-the-mill family. For one thing, they are among the richest of the incalculably rich. According to those closely familiar with the family enterprises, a quick tally of the net worth of the Shreveport courtroom during Frania Lee’s testimony would have yielded a figure of $2–3 billion if the Hunts were to “sell everything they own tomorrow.” However, counting the enormous principal of their trust funds (under the structure of the trusts, the children receive only the income) the Hunt family wealth is well in excess of $5 billion. About half of that comes directly from H. L., but an almost equal amount has been accumulated by the children themselves, primarily those in the first family. Five years ago, when he still had his great Libyan oil field, Bunker Hunt was the richest individual on earth, with reserves he estimated to be in excess of $16 billion. Even without that ocean of oil, the Hunts may still be the world’s richest non-Arab family.

Surprisingly unassuming in both presence and personality, they often seem as ordinary as the local barber. At the same time, they continually find themselves in the most extraordinary situations. In addition to their activities in high-flying international business ventures, they have been embroiled in such diverse worlds as the horse racing at Ascot in England, downtown redevelopment in Dallas, and CIA intrigue both at home and abroad. They have also been embroiled in a number of highly controversial lawsuits and countersuits both criminal and civil, and have hence become controversial themselves. To much of the outside world, they epitomize the Texas oil rich. To their neighbors in Dallas, they are anything from municipal nuisances to local celebrities and business geniuses. Like their present wealth, part of their present problems are of their own making; the rest result from their father’s unusual legacy. As one close associate observed, when they are not fighting among themselves, the first and second families are usually fighting their father’s image.

At the trial in Shreveport, the first and second families found themselves fighting both of those battles and the third family of Frania Tye Lee. As far as the court was concerned there were just two main issues. First, had Mrs. Lee unwittingly been H. L.’s bigamous wife, or had she been, as the Hunts claimed, just another of the old man’s mistresses? Second, was the release she signed in 1942 still valid and binding? However, behind these narrow legal points lurked much larger questions of identity, wealth, and, most of all, the priority of their father’s affections. For these and other reasons, this was not just another trial, but like the feuding between the first and second families and much of the preceding Hunt history, it was a financial and emotional imbroglio, a battle over both love and money.

In the opening pages of Hunt Heritage, H. L. informs the reader that “The Hunts have long been among the most constructive of the early settlers in this country.” One Hunt, he says, was a chaplain for Captain John Smith, another was the first governor of Georgia, still others were officers in the Revolutionary War. His mother’s side, meanwhile, were Huguenots who arrived in the U.S. in 1797 and later migrated west to Illinois. There, Ella Rose Myers married the first Haroldson Lafayette Hunt, an industrious farmer and banker who had moved north to escape Reconstruction. H. L., Jr. (nicknamed June), was born on February 17, 1889, the youngest of eight children.

However, nothing in Hunt Heritage hints at one of the main forces in his personality—the fact that he was always oversexed. According to Stanley H. Brown, Hunt’s only book-length biographer, it all began with H. L.’s nursing at his mother’s breast openly and frequently until he was nearly seven years old. In later years, Brown writes, Hunt would recall the experience quite clearly, and retell it “as blandly as if it had been nothing more than information about the acreage and crops of the family farm.” In light of H. L.’s subsequent sexual exploits, that was probably about the way it really deserved to be told.

For most of his early years, H. L. was the black sheep of the family. He ran away from home at the age of fifteen and drifted across the country working in kitchens and on ranches, farms, and lumber camps. Though his mother was a schoolteacher, he avoided formal education like a disease and spent as little time as possible doing his share for the family businesses. Instead, he used his great mathematical ability to become a professional gambler, one of the so-called “card locators” who memorize every deal and predict the sequences of the cards. Always receptive to opportunities for a fast buck, he also became a cotton and real estate speculator. In his spare time, he exercised his insatiable eye for attractive young ladies.

Hunt was still plying these trades in the little town of Lake Village, Arkansas, just across the river from Greenville, Mississippi, when his mother died. Two months later, in November 1914, he married Lyda Bunker. Like his mother, Lyda was short, dark-haired, and a schoolteacher. The daughter of a prominent Lake Village merchant, she also proved to have a disposition of limitless magnanimity and considerable inner strength. Years later, in Hunt Heritage, H. L. would credit her with “about ninety per cent of our financial successes.” Other family members would go even further. “Lyda was the one who held the family together,” remembered one. “She was the person who really forced H. L. to make something of himself.”

There was no question that she had her hands full. In the early years of their marriage, H. L. continued to gamble and speculate and run into debt and climb out again. Lyda, meanwhile, started having children—Margaret in 1915, Hassie in 1917. Soon she began getting after H. L. to find a steady job. As usual, he would not listen. Devastated by the Panic of 1921, H. L. left his wife in Lake Village and took off to the oil boom town of El Dorado, Arkansas. Shortly after his arrival, Hunt opened up a popular gambling house and began trading in oil leases. That summer, he drilled his first well. Typically, it was a producer, as were most of the others that followed, and in 1922 H. L. moved his family to El Dorado, where the couple’s third child, Caroline, was born.

Still a relative novice in a relatively young industry, H. L. soon found the oil business of the day suffered the same boom-and-bust cycles common to his other speculative activities. He was rich one day, back in debt again the next. Prices fluctuated without rhyme or reason. There were difficulties on the home front, as well. Early in 1925, Lyda gave birth to another girl, this one named after her. The child lived only one month.

About this time, H. L., now 36, went through what modern self-help experts would call a “mid-life crisis.” Dissatisfied with the ups and downs of his drilling activities, he sold his remaining production to a major company for a promissory note and discounted the note for cash. Then, with Lyda pregnant once again, Hunt announced that he was quitting the oil business and going to Florida to try his luck in “the wild real estate boom everybody was talking about.”

In the summer of 1925, Hunt arrived in Tampa. There, just as the real estate boom was reaching its peak, he met Frania Tye, a 21-year-old real estate salesgirl who would become the mother of his second set of offspring.

The daughter of Polish Catholic immigrants originally named Tyburski, Frania (who also went by the name Frances) had grown up with seven brothers and sisters in Buffalo, New York, where her father worked as a contractor. By the looks of her old photographs, she was absolutely ravishing: a short, dark-haired beauty with blue eyes that shone like giant marbles and strong, well-proportioned features. In her Shreveport testimony, Frania went to great lengths to stress how innocent she was when she met H. L., but Hunt family attorneys suspected otherwise. Shortly before coming to Florida, she had broken off an engagement to a young man by the name of Paul Kurtz. She had also participated in a Buffalo court hearing styled “In Re Frances Tyburski” involving the appointment of a guardian. Exactly who needed a guardian and why never came out at the Shreveport trial over half a century later, in part because the records of the case had mysteriously disappeared. However, it was clear from their questioning that the Hunt family attorneys suspected the guardian was not for Frania, but for a child she may have had by Paul Kurtz.

In any event, Frania later claimed that Hunt introduced himself to her as “Major Franklin Hunt,” and began a rather bumpy, “whirlwind” courtship, characterized by repeated forward advances, which she repeatedly refused. Finally, she said, Hunt got serious and proposed. On November 11, 1925, Armistice Day, the two of them were married by a justice of the peace in Ybor City, Florida, at a wedding arranged and witnessed by a Hunt associate called Old Man Bailey. At this time, she said, she was not in love with Hunt, just very fond of him. “I don’t think I fell in love with him until after we were married,” she told the court in Shreveport.

Strangely enough, the only documentary evidence Frania could offer to prove her marriage to “Franklin Hunt” was a voided entry in a marriage license ledger book. That entry was discovered by Mrs. Lee’s son only a few months before the Shreveport trial, after several others, including Frania herself, had vainly searched the records at various times over a period of many years. According to the undisputed testimony of a documents expert, the entry was made in different handwriting than every other entry in the book, before or after. A great deal more about the entry might have been determined by dating the ink. However, not long after attorneys in the case made certified copies of the entry, that portion of the record book was mysteriously sliced out—the first time such a thing had happened in the history of the Hillsborough County, Florida, clerk’s office.

Whether or not they really married, there is no doubt that Frania and Hunt became sexually intimate, for early in 1926, as Hunt’s wife Lyda was giving birth to Nelson Bunker Hunt back in El Dorado, Frania moved to Shreveport, Louisiana, pregnant with Hunt’s child. On October 25, 1926, she gave birth to a boy who was christened Howard Lee Hunt. Two years and one day later, she gave birth to her second child by Hunt, a girl they named Haroldina. Meanwhile back in Arkansas, H. L.’s first family also continued to grow. On March 6, 1929, five months after Haroldina was born, William Herbert Hunt was born to Lyda.

Although it is impossible to pinpoint H. L.’s whereabouts during each phase of this reproductive period, all indications are that he was spending most of his working hours drilling for oil and trading leases in and around Shreveport and El Dorado, a radius of some 80 miles. Then early in 1930 he went to East Texas and began to put together the biggest deal of his career: the acquisition of the famous Dad Joiner leases that proved to be the foundation of his fortune. Hunt closed the deal with the hapless Joiner that spring for $1.3 million in cash and the promise of a small interest in the future production of the leases. Then, as Joiner and others angrily realized the coup he had pulled and prepared a barrage of lawsuits to regain the leases, H. L. quickly set about developing the field that would eventually net him over $100 million. Alert to the fact that Hunt had just bought himself an ocean of oil for a relative pittance, newspapers all over the region reported the deal in banner headlines.

By this time, Frania was pregnant with still another child. In the late spring or early summer of 1930, she moved to Dallas, where she lived in a house on Versailles Avenue in Highland Park. Shortly afterward, she and her sister Jennie opened a beauty parlor in the Highland Park shopping center. On October 28, Frania gave birth to a second girl, Helen. Realizing that his future now lay in East Texas, H. L. moved Lyda and the children of his first family from El Dorado to Tyler and opened offices in the People’s National Bank Building. However, H. L. himself took an apartment in Henderson, which put him much closer to the Joiner leases, and set to work on his giant oil bonanza with his favorite son, fourteen-year-old Hassie, at his side. On August 2, 1932, his wife, Lyda, gave birth to the couple’s last child, a son they named Lamar.

By the spring of 1934, H. L. Hunt was already a multimillionaire, and Frania, with seasonal regularity, was pregnant once again. It was then that H. L. and Frania suffered the first rupture in the long series of breakups and reconciliations that finally led to the stormy settlement scenes in the Hotel Adolphus in 1942.

Exactly how that rupture came about is very much open to question. Frania later claimed that the precipitating factor was a friend’s sudden revelation to her that the man with whom she had supposedly lived for nine years of matrimonial cohabitation was not Major Franklin Hunt, but the famous H. L. Hunt, a man already married and the father of another family.

That story is at best hard to believe. Not only did she and Hunt give their first child the initials H. L. and their second the unusual name Haroldina, but Frania also admitted that during the entire period from 1925 to 1934, Hunt never once took her out socially and never received any letters or packages at any of the four residences she claimed they shared in Shreveport and Dallas. She said that on a number of occasions Hunt did take her on trips to the East Texas oil fields, and that the two of them may even have discussed the headline-making Dad Joiner deal. But “somehow,” she insisted, she did not know he was H. L. Hunt. She claimed that whenever her suspicions had been aroused, Hunt told her H. L. was his uncle.

The recollections of two old-timers from the Tyler and El Dorado days suggest that Frania’s contention is a lie. According to Veatrice Hardin Spragins, the widow of a Hunt Oil employee, and Gladys Taylor McCrea, a former Hunt Oil secretary once married to a Hunt family cousin, H. L. kept Frania with him at the Blackstone Hotel in Tyler and the Randolph Hotel in El Dorado, while using both places to conduct business and meet with associates. Both Mrs. Spragins and Mrs. McCrea recalled in recent interviews that Hunt concealed Frania’s true identity and the true nature of their relationship by introducing her as the sister of his sidekick, Frank Grego. On the occasion of Grego’s funeral, Mrs. McCrea said, Hunt even took Frania out to the family’s house in Tyler, where Frania met Hunt’s wife Lyda.

“She knew he was H. L. Hunt,” Mrs. Spragins averred. “She couldn’t help but know it.”

In a pretrial deposition Mrs. Lee herself testified to seeing Hunt’s oldest daughter, Margaret, at a party next door to Frania’s house on Versailles Avenue in the spring of 1934. Although Frania did not then reveal her own identity, Hunt family sources claim that encounter may have been what really prompted Frania to break up with H. L.

Whichever version is correct, Frania did pack up her belongings and her three children, moved to a house in Great Neck, N.Y., and “immediately” began calling herself “Mrs. H. L. Hunt” even though she realized she “wasn’t Mrs. anybody.” On October 14, 1934, she gave birth to her fourth child by H. L. Hunt, a boy christened Hugh Lee Hunt.

At this point, Hunt seemed to turn his attention back to his first family. The following year, he set up the 1935 “Loyal Trusts” that became the foundation for the fortunes of his six children by his wife, Lyda. But Hunt also maintained some sort of relationship with Frania. According to testimony corroborated by several former neighbors, Hunt continued to see Frania while she lived in Great Neck, often stopping to gamble at local racetracks along the way. These witnesses said that Hunt went by the name of “Hunt” or “Major Hunt,” and that he treated Frania and her children as would a “normal” husband and father.

Easily the most dramatic evidence Frania offered of her continuing relationship with Hunt was a collection of love letters and telegrams. One dated December 23, 1937, and addressed to “Mrs. Fran Hunt” went like this:

Running now a little late

But hoping to keep our date,

So strong is the urging,

My engine is surging,

So anxious to see what a family I have.

My hopes are sublime

To arrive on time.

It was signed, “Love and laughter longingly, Daddy.”

Frania also told the court in Shreveport that Hunt had tried many times to convince her to become a Mormon. Despite her refusal, Frania apparently did not want to give up her peculiar relationship with Hunt. She said that in 1939 or 1940 Hunt asked her to move back to Texas “to be closer to him.” Acquiescing to his request, she took up residence in a comfortable house in Houston, which she said he paid for, as he had all her other houses. Even though she had long since discovered the existence of Hunt’s “other” wife and family, she presented herself to Houston society as “Mrs. H. L. Hunt.”

Of course by this time Hunt had pretty much completed the development of the East Texas field and was becoming fairly well-known all over the region. In 1938, he had moved Lyda and the children of his first family from Tyler to Dallas, his new headquarters city, and had purchased the Mount Vernon–style mansion on White Rock Lake. With two women in the same state now going by the same name, it was only a matter of time until a crisis occurred.

The scene was a fancy River Oaks party at which Frania was to be introduced to the cream of Houston society. In the middle of the party, Frania said, she received a phone call from an anonymous woman who threatened to blackmail her by revealing that she was “only a mistress of H. L. Hunt.” Afterwards, she said, she received dozens more of the same sort of calls. Distressed and embittered by Hunt’s refusals to come to Houston to help her, she packed up all four of her children, took them to a hotel in Dallas, telephoned their father to come take care of them, and left town. In the ensuing confusion, Frania first returned to Dallas to pick up the children and met Hunt’s oldest daughter, Margaret. Then Frania, H. L., and Lyda ended up in what must have been a most memorable confrontation.

“Hunt did a lot of the talking,” Frania recalled afterwards. “Lyda and I were strangers. We looked each other over. I arrived at the conclusion that Mrs. Hunt was the finest woman I ever met. She was very kind, very sweet, very understanding.”

According to both families, Frania and Lyda then had a girl-to-girl talk during which the first Mrs. Hunt offered to do anything she could to help, including adopt Frania’s children. Without detracting from the magnanimity of Lyda’s gesture, Hunt family sources say that Lyda’s offer was at least in part motivated by her desire to protect her own children’s share of the Hunt fortune. (“Lyda was a very gracious woman,” said one, “but she was not dumb.”) In any case, Frania refused the adoption offer.

At Hunt’s suggestion, she moved from Houston and took her children to Los Angeles, where she enrolled them in school, still under the name Hunt. Hunt then set up the so-called “Reliance Trusts” for Frania’s four children. Composed primarily of producing oil and gas leases, each trust provided a yearly income of roughly $6,000. The “settlor” named for these trusts was “Mrs. Frania Tye Hunt.”

Apparently unsatisfied with the “Reliance Trusts” and her situation in general, Frania returned to Dallas a few months later with her best friend, Martha Kreeger, and two Texas lawyers. After describing the intense melodrama of Hunt’s million-dollar offer, Frania told the spellbound audience at the Shreveport trial that at the time she had no idea how much H. L. Hunt was actually worth. Had she known, she said, she would never have settled for the amount she eventually got.

Longtime Hunt attorney Ralph Shank, who represented H. L. in the negotiations, remembered the situation quite differently when he was called to the stand. Shank testified that he showed Hart Willis, one of Frania’s lawyers, a financial statement listing Hunt’s community property as worth $15 million. Had Frania been able to prove she was Hunt’s wife, that would have made her share equal to $7.5 million. Shank said that Willis represented Frania skillfully and forcefully throughout the negotiations, and added that to his knowledge, Hunt never admitted marrying Frania and never promised to recognize her or her children in his will. Shank did acknowledge, however, that H. L. had asked him to research the bigamy statutes in preparation for the talks.

At any rate, on January 24, 1942, Frania signed a 62-page statement denying she was married to Hunt and a blanket release indemnifying him from any future claims. Hunt wrote her a $300,000 check and a $25,000 check for her attorneys and started the $2000 lifetime monthly payments. Twelve days later, Frania married a former Hunt Oil Company employee and military veteran named Colonel John W. Lee. Lee adopted Frania’s children, and gave them his surname.

To this day, the circumstances of the marriage remain unclear, in part because both Lee and Frania refuse to discuss it. However, Gladys Taylor McCrea, who at this time was still married to one of H. L.’s cousins, said recently that the marriage was simply one of convenience. “Colonel Lee married her to give those kids a name,” Mrs. McCrea recalled. “He was very handsome, and he had been very much in love with another girl who was already married with four children. But the girl was a Catholic and she wouldn’t get divorced and remarry him because of her religion. After he married Frania, he lived by himself in the Baker Hotel in Dallas. Frania stayed around Dallas for a while, then she went off on her own. It was so much ado about nothing.”

In 1955, shortly after the death of Hunt’s first wife, Lyda, Colonel Lee and Frania were divorced. Mrs. McCrea and others have speculated that the obvious reason for the divorce was Frania’s still burning desire to marry H. L. If so, Frania’s hopes were never realized. Instead of returning to a dream come true in Texas, she continued to live in Atlanta, Georgia, where she strove to become a prominent art patron despite persistent rumors that she was “moneyed” by H. L. Hunt.

At the Shreveport trial Frania testified that as her children grew up she taught them to “love and respect Hunt” but not to use his name. According to both sides of the story, the Lee children rarely saw their real father, and when they did, they were often rejected or quickly shunted away. Then, tragedy began to befall them. Haroldina, the oldest daughter, suffered a severe mental breakdown. Helen, the other daughter, was killed along with a long list of well-known Atlanta art lovers in a Paris plane crash in 1963. Howard, the oldest, died of cancer before his mother had her day in court in Shreveport.

Meanwhile, Hugh Lee, the youngest, engaged in an apparent pursuit of his identity that included no less than three name changes from his adopted name through such variations as “Hugh R. Lee” and “Hue R. Lee” to his original name, Hugh Lee Hunt. Tall and broad-shouldered with a wide, puffy face that made him an even more striking likeness of his natural father than most of the children of the first and second families, Hugh Lee tried even harder than his brothers and sisters to win H. L.’s love and recognition. The old man responded with at least one sizable underwriting on a loan, but Hugh Lee nevertheless encountered one financial setback after another, including the bankruptcy of his major company, and a long list of plaintiff lawsuits. The father of eight children, he later became one of the principal behind-the-scenes figures in his mother’s lawsuit against the Hunt estate in Shreveport.

H. L.’s life also grew more complicated after the 1942 settlement. About the same time he was breaking with Frania, H. L., then 53, was taking up with an attractive 25-year-old legal secretary named Ruth Ray. In fact, some members of the Hunt family contend that H. L.’s fascination with Ruth, and Frania’s jealousy over it, were the real causes of the 1942 settlement.

Hunt met Ruth in Shreveport, where she was working for a law firm that handled Hunt Oil Company business in the area. The youngest of seven children, Ruth had come from a reasonably affluent family in Idabell, Oklahoma. She was short, curly-haired and full-figured, and she possessed large, wide-jawed facial features like Frania’s. But, unlike Frania, she was not quick-tempered and demanding. In fact, Hunt’s associates remember her as nice and sweet almost to a fault. A devout, born-again Southern Baptist, neither naive nor unintelligent, she knew full well, as she proved time and again in later years, exactly how to please H. L. Hunt and how to take care of herself and her children.

In April 1943, Ruth Ray went to New York and gave birth to her first child by H. L., a boy the couple named Ray Lee. Over the next seven years, Ruth bore Hunt three more children, all of them girls: Ruth June, Swanee Grace, and Helen La Kelley. Like the children H. L. had by Frania, all four were born while Hunt’s first wife, Lyda, was still alive. But instead of parading herself around the state as Mrs. H. L. Hunt, Ruth Ray lived quietly under the assumed name of Wright. H. L. provided her with a house in the White Rock Lake area not far from his own Mount Vernon estate and sent the children to private schools. Ruth told Ray who his real father was, but taught him and his sisters to call their father “partner.” In later years, she would send her daughters over to sing for him when he was blue. H. L., in turn, provided amply for Ruth’s four children by setting up their “Secure Trusts.”

As H. L. was beginning his second family (actually his third), his 26-year-old son, Hassie, the pride and joy of his first family, suffered a mental breakdown. Pressured to live up to H. L.’s special standards ever since he was a small boy, Hassie had exhibited fits of odd behavior on and off for several years. (“I remember one time when Mr. Hunt was taking him through the oil fields,” recalled a Hunt associate. “Hassie jumped out of the car and started rolling around in the oil pits. He got oil and grease all over him. It was really a mess.”) Finally, he threw a terrible tantrum that landed him in the hospital. When he was released, he withdrew from the world almost completely. The only manner in which he could discuss anything pertaining to himself was in the third person. H. L. built Hassie a special house in back of the Mount Vernon estate, and hired 24-hour attendants. Convinced that Hassie—like himself—possessed some mystical power to find oil, H. L. tried everything from providing him with women to supplying him with Valium and inducing him to submit to a variety of newfangled cures. Nothing worked. In an interview many years later, Hunt’s daughter Margaret flatly asserted, “My father destroyed Hassie.”

In April 1948, a few months after Hassie’s breakdown, Fortune and Life magazines ran the first national stories on H. L. Hunt, asking rhetorically, “Is this the richest man in the U.S.?” The two publications estimated the value of Hunt’s oil properties at $263 million and his gross weekly income at $1 million. Six years later, on the occasion of his sixty-fifth birthday, Hunt held a press luncheon in New York City at which a spokesman announced, in introducing him, that Hunt was worth about $2 billion and had an annual after-tax income of $54 million.

Although amply provided with their shares of the old man’s money, neither Lyda nor her other five children saw as much of H. L. as Hassie did. As one family friend remarked, H. L. was “an odd fellow, very much a loner,” and his children grew up in “rather a one-parent family.” Having grown fat and matronly from years of childbearing, Lyda was well aware of at least one of her husband’s other families. But she still maintained a remarkably pleasant disposition, and, according to those who knew her, managed to raise her children without often raising her voice. She did not, however, have much luck in smoothing the rough edges of her eccentric husband. After the family moved to Dallas, H. L. applied for membership in Brookhollow Country Club and even signed up for golf lessons but was blackballed by members who disapproved of his treatment of Joiner and others in the oil business. But Lyda did succeed in instilling her daughters and, in varying degrees, her sons with a sense of the proper social attitudes and style. Friends from happier days said later that she also began to show, if only discreetly, some of the strain of her long marriage to H. L.

“Occasionally, she would call me and want me to come to Dallas and see a show with her,” one friend recalled. “She always seemed quite lonely.”

By this time, of course, Lyda’s children were mostly grown, and, backed by their 1935 trusts, already beginning to make names for themselves. Devoted to their mother, they often found themselves even more drawn to H. L. and to the oil business precisely because of their old man’s absences and relatively minimal efforts to influence them.

Margaret, the oldest, reigned as queen bee. Short, dark-haired—and chubby when she was young, like her mother—Margaret grew into a trim, strong-minded lady with sharp, finely etched features that matched the edges of her disposition. At seventeen she began traveling with H. L. on his business trips, learning the ins and outs of the oil industry as few young women of the day—or few young men, for that matter—had an opportunity to do. The coldest, most snobbish member of the family, she made no pretense of enjoying the company of common folk. She attended exclusive Mary Baldwin College and later joined the Dallas Women’s Club, the Daughters of the American Revolution, and several other like-minded organizations. More strictly conservative than either her father or her brothers, she seemed dedicated to reminding the family that they were Hunts and should act accordingly.

Margaret married a tall, red-haired accountant named Albert Galatyn Hill. Despite some initial friction with H. L. over the fact that he was ten years older than Margaret, Hill soon joined the boards of the main family companies, but his main interests were playing tennis and taking care of the Garden of the Gods Club, a plush resort he built in Colorado Springs, Colorado. Although Margaret herself seldom initiated any business activities, she retained a kind of ultimate veto power over financial matters and most every other sort of family activity. She gave Hunt three grandchildren, two girls and a boy.

Caroline, by contrast, impressed everyone with the gentleness of her disposition. Younger and much less strident than sister Margaret, her style was more contemporary and less formal. After attending the University of Texas at Austin, she married Louis B. Sands. The couple had four children and were divorced. Caroline then married Hugo “Buddy” Schoellkopf, a scion of one of the fine old families of Dallas. By far the most low-key of Lyda’s children, Caroline maintained such a moderate profile that, as one Dallas society writer was led to observe, “few people even knew she was a Hunt.”

Not surprisingly, the mantle of first family leadership soon fell to the next oldest son, Nelson Bunker. Named for his maternal grandfather, Bunker possessed a personality formed in the mold of H. L.’s. His bout with formal education is just one example. After attending Culver Military Academy and the Hill School in Pennsylvania, Bunker enrolled at the University of Texas only to hear his first-semester geology professor announce that the government should control all natural resources. Bunker promptly quit school and joined the Navy, where he saw limited action in World War II. Returning home from the service, Bunker went right to work in the oil business. In 1948, at the age of 22, he struck oil in Scurry County; that field is still producing and has reserves estimated at $7–$8 million.

Bunker’s later successes did not come so easily. Determining that the future was in the international oil business, he embarked on an ambitious $35 million drilling program with the government of Pakistan in 1955. After more than $11 million of dry holes, he decided that he should look elsewhere. He then sunk $250 million more into the Middle East and North Africa. This time the gamble paid off: In 1961, Bunker brought in the colossal Sarir Field in Libya, one of the largest single discoveries in history. Bunker later estimated the field’s reserves to be roughly eleven billion barrels, worth about $35 billion at the then prevailing prices and some $62 billion at current world-market prices. A fifty-fifty partner in the deal with British Petroleum, that made Bunker’s net worth at the time in excess of $16 billion. He was, at least on paper, the world’s richest man.

Bunker lost the Sarir Field in 1973 when Colonel Qaddafi’s new radical regime nationalized the oil industry. Bitterly accusing the world’s major oil companies of using him as a “guinea pig” to test Qaddafi’s politics, Bunker filed a $13 billion lawsuit against Mobil and thirteen other international giants for allegedly violating a 1971 agreement to present the Libyans with a united price-negotiating front. In that suit, which is still pending, Bunker indicated that his profits from the Libyan venture amounted to over $100 million per year.

About the time of the Libyan takeover, Bunker became distressed over the declining value of paper money and began investing in commodities. At one time in the early seventies, he owned an estimated thirty million ounces of silver, which he kept in nondescript warehouses around Dallas. In the summer of 1976, he and other family members spent over $200 million on soybean futures. In both instances, however, word of the Hunt holdings leaked out, and after initial rises, prices of both commodities plummeted. Some financial pundits reported that Bunker had suffered tremendous losses, others credited him with at least marginal profits. Bunker himself said that after all the buying and selling, he came out “just about even or maybe a little behind.”

Although Bunker denies it, those closely familiar with his financial interests maintain that he is still a billionaire despite his troubles. The foundation of his wealth and the fortunes of the other members of the first family is Placid Oil Company, reputedly the world’s largest privately held company, which he and his brothers and sisters own through their 1935 trusts. With estimated oil reserves worth in excess of $2 billion, Placid generates a gross annual income of $300 million, and may one day generate even more when the Hunts develop their choice leases in the North Sea and Alaska’s Beaufort Sea. With brothers Herbert and Lamar, Bunker also owns a one-third interest in Penrod Drilling, the largest privately held drilling contractor in the world. He owns over a million combined acres of ranches in Texas, Oklahoma, and Montana, and four million acres in Australia. He has farmland in Mississippi and California, three large horse- and cattle-raising acreages in Kentucky, the country’s largest silver mine, and substantial interest in coal. In the early seventies, he held what one local agriculture writer hailed as the world’s largest auction of Charolais cattle.

For recreation, Bunker likes to dabble with breeding race horses. He currently owns over 1000 thoroughbreds in the U.S., England, Ireland, and France, including the progeny of his horse Dahlia, a former European grand champion.

Close associates contend that Bunker himself probably does not know exactly how much all this totals. “He’s just not a possessor,” said one. “I can’t dream of him making a list of his holdings. Even so, it’s safe to say that Bunker is richer than his old man ever was.”

Bunker naturally shies from such comparisons. “I never had any ambition to top my father because he was a phenomenon,” he said in a recent interview. “Of all the fellows I ever met, he was the smartest. He had a natural mathematical mind. I never had the feeling I had to compete with him.” Bunker added that his only real goal was “to do well, to make a profit, because that’s how you judge success or failure in life, in business. Money never really meant anything to me. It was just something that if you wanted to spend it, you would have it. My father never really cared about money, either. It was just sort of how they kept the score.”

The quintessential good ol’ boy, Bunker, father of four children and grandfather to three more, typically wears cheap suits and cheap shirts. Once, when a Sports Illustrated writer asked why he departed from his usual raiment to don morning coat and top hat for the English Derby at Epsom, he said, “I guess it’s a case of monkey see, monkey do.” His five-foot-eleven-inch frame has always sagged with excess avoirdupois, but lately he has let his weight balloon to over 300 pounds. Still, he continues to indulge in favorite delights like chocolate milk, ice cream, and cheeseburgers. A self-described “heavy sleeper,” he has been known to doze off at the most inauspicious moments, including in the midst of his own trial for illegally wiretapping a group of Hunt employees. Declining such rich man’s perquisites as a chauffeur, Bunker drives a rather undistinguished maroon-and-tan Cadillac and claims to spend nothing on personal security. Asked once about his apparent casualness, he said, “Why should I worry? Worrying is for people with strong intellect or weak character.”

Although Bunker sometimes comes off as a fat old squinty-eyed bumbler, he is sharp and crafty and gifted with the same natural mathematical mind for which he praises his father. “Bunker has flashes just like H. L. used to have,” says one family member. “Sometimes he’s absolutely brilliant. The rest of the time, you wonder whether he’s really there with you or not.”

Although he is not power hungry in the typical political sense, Bunker has become accustomed to ruling the family roost. He is used to getting his way and becomes impatient when he does not. (Once, in the midst of some particularly complicated litigation, he asked an associate to give him a complete summary of the day’s testimony in less than a minute “or don’t bother telling me about it at all.”) He can also be frightfully impulsive. Departing from the Hunt tradition of non-involvement in publicly held corporations, he and his brothers invested $3 million in the stock of Great Western United (the nation’s largest sugar beet refiner and the owner of the Shakey’s Pizza Parlor chain) on the basis of a few pages of notes an in-law had scribbled during a broker’s oral presentation. A short time later, the Hunts discovered alarming management problems at GWU and invested over $20 million more to take over the entire company.

A sententious soul, Bunker does not smoke or drink and disdains those who do. Despite his hefty size, he is remarkably light on his feet and tries (with varying success) to maintain a regimen of exercise, mostly jogging and raquetball. Like his father before him, he is not particularly enthusiastic about charity and has been continually criticized for failing to do anything to promote the civic good of Dallas. On the other hand, he recently agreed to raise $1 billion for the Campus Crusade for Christ.

The most curious aspect of Bunker’s character is ideological. A segregationist and staunch conservative, he is the nation’s largest contributor to the John Birch Society. He believes that the idea his father articulated in his utopian novel, Alpaca, that votes should be accorded on the basis of how much money a person has, is “a little unusual, but not a bad idea,” and certainly a great deal better than allowing suffrage for people on welfare. Bunker also detests federal government intervention and “harassment.” One of his favorite examples is the Commodity Futures Trading Commission’s unprecedented action against the Hunts in the soybean futures controversy last May. Claiming that the Hunts had acted together to violate the Commission’s three million limit on the number of bushels any one group or person can control at one time, the CFTC took the unusual step of making the Hunt family’s 21-million-bushel position public when it filed its charges. Naturally, the price of the beans quickly fell through. The CFTC justified its actions by charging that the Hunts’ holdings amounted to a virtual corner on the market, which might “threaten disruption of the soybean futures market” and which “could cause serious injury to the American public.” Bunker, seemingly oblivious to the effects his family’s alleged actions might or might not have on the public, accused the CFTC of trying to “manipulate soybean prices to drive the prices lower and apparently repeal the laws of supply and demand.”

“We’re sort of a favorite whipping boy,” he allowed afterwards. “We’re conservative and the rest of the world is socialist and liberal. And as long as they want to jump on somebody, they want a name and they want somebody that’s on the other side. If I were a liberal socialist, I don’t think you’d ever—hardly ever—see my name in the papers.”

At the same time, much like a left-winger, Bunker has developed an intense dislike for the CIA. Part of this antipathy stems from Bunker’s days in Libya when, he claims, the CIA tried to place a man in the Hunt organization there. Bunker says that when he refused the CIA request on the grounds that the oil producers’ arrangement with the Libyan government precluded him from employing the agents of his own or any other government, the CIA planted a man in his company anyway. As further events unfolded, Bunker claimed to see evidence of a long-term pattern of CIA surveillance of his father and the rest of his family beginning at least as early as the late fifties and continuing through the present day.

“The Eastern Establishment pretty much calls the shots in this country, and they like to keep the interlopers down,” Bunker explained recently. “My father was an individual spirit who couldn’t be controlled by normal establishment pressure. I think they put people on our payroll to watch him and give him as much trouble as they could.” There are some very specific reasons for Bunker’s apparent paranoia, as our story will show a little further on.

Bunker’s battles against big government and the CIA often evoke sympathy from even the most hostile observers until the matter of the assassinations arises. Perhaps the blackest and most lasting mark against Bunker Hunt is that he—not his father—was responsible for running the Dallas newspaper advertisement that accused John F. Kennedy of being a “traitor” on the day Kennedy was killed. Subsequently, H. L. was one of the many people various assassination buffs blamed for the murder. So far, however, the closest thing to a direct link is the accusation of convicted felon John H. Curington, an embittered former employee Bunker and Herbert accused of embezzling millions of dollars. In an interview he granted the gossip-mongering National Enquirer, Curington, who would later make a sensationalistic appearance at Frania Lee’s trial in Shreveport, claimed that Marina Oswald, wife of accused assassin Lee Harvey Oswald, appeared in the Hunt Oil Company offices to see H. L. the day after Kennedy was killed. Others, with even slimmer claims to first-hand knowledge, and with no proof, have speculated on the Hunts’ possible involvement with Martin Luther King’s convicted assassin James Earl Ray. Most of these more radical rumors involved H. L., but as the old man’s principal heir, Bunker seems destined to be plagued by them as well.

Herbert Hunt, the next oldest, is the steadying force of the family. Because he so often acts in partnership with Bunker, Herbert generally gets bumped to second billing and buried under words like “stiff” and “distant.” The descriptions are unfair. Where Bunker has the ability to turn on a childlike charm, Herbert is the friendliest and most affable of the Hunts, the one who seems most in touch with everyday reality. Bunker, the chairman of the board of Hunt Energy, the first family’s umbrella company, concerns himself with the overview; Herbert, the president, contributes sophistication, balance, and attention to detail. At the same time, though, he seems more uptight than his older brother and less sure of himself.

An avid breeder of turkeys, chickens, and other animals as a child, Herbert attended college at Washington and Lee, graduating with a degree in geology. Then he went right to work in the oil business. After showing he could uphold the family tradition of finding oil, Herbert sunk $100 million of family money into Penrod Drilling and made the company a leader in deep drilling. In the early seventies he agreed to bail out beleaguered Marathon Manufacturing Company of Houston; the Hunts’ 14 per cent interest has since appreciated by two-thirds. Along with cousin Tom Hunt, Herbert also took responsibility for representing the family interest on the board of Arch Minerals, a large independent coal producer the Hunts own in partnership with Ashland Oil Company. He has also developed separate personal ventures in both Texas and Florida real estate.

“A lot of people think Herbert and Bunker do everything together,” Herbert’s son Doug, a budding Hunt Oil executive, said recently. “But the truth is they spend about 45 per cent of their time on their own stuff.”

Less casual in style than Bunker, Herbert follows the conventional Texas executive image. He wears nicely tailored suits to the office and cowboy boots and Levi’s to relax. He is a member and past president of a number of oil industry associations and clubs and a deacon in Highland Park Presbyterian Church. An avid skier, he frequents the slopes of Vail, Colorado, where he has a second home. Like his father, he is interested in health food diets, most recently the diet of the slow-aging Hunsas in Tibet. He also likes to mow his own lawn. In 1950, Herbert married a comely El Paso–born Hollins College student named Nancy Jane Broaddus. The following year, Caroline Lewis, another Hollins College student who finished at SMU, married Bunker.

Lamar Hunt, the youngest member of the first family, turned out to be the most publicly visible, because of his involvement with his empire of professional sports teams. In 1959, at the age of 26, he started the American Football League, complete with his own personal football team, the Dallas Texans, now the Kansas City Chiefs. In subsequent years he branched into basketball (an 11 per cent ownership of the Chicago Bulls), soccer (the Dallas Tornado), and tennis (the World Championship Tennis circuit). He also owns a theme amusement park in Kansas City called Worlds of Fun, as well as various partnership interests in his brothers’ oil and drilling enterprises.

On first impression, Lamar seems to be the most preoccupied of the Hunt brothers, the one who is always off in his own world. A faithful jogger (as is brother Herbert), he has been known to conduct important business attired in his running togs. However those who deal across the table from him attest that he is deceptively sharp in his business activities and a very tough bargainer. He can rattle off the vital statistics of his various sports franchises with unfailing accuracy and seldom suffers the boom-and-bust cycles characteristic of his brother Bunker’s wheeling and dealing. As one family confidant puts it, “Lamar can take care of his things.” Partly for that reason, Bunker and Herbert have been trying to get him to come back into the oil business with them. Still, Lamar seems more determined to make a name for himself apart from the family.

The central fact of Lamar’s middle life is his marriage to Norma. Divorced from his first wife, Lamar met Norma, then a suburban schoolteacher, when she signed on as a hostess for Lamar’s Dallas Texans football team. Always somewhat reticent, Lamar’s personality began to blossom; Norma, meanwhile, became simultaneously more stylish (enter the pile of blonde hairpieces and designer clothes) and even more conservative than most of the members of her new family. The two of them moved into Jimmy Ling’s vast North Dallas mansion, a baroque palace surrounded by rolling hills and quiet duck ponds, and let the large wrought iron “L” that Ling had put on the front gate come to stand for “Lamar.”

Despite their individuality, the most significant thing about the Hunts of the first family is their cohesiveness. With a clan membering over 30 strong, including present and former spouses, children and grandchildren, they naturally have their internal disagreements. (“Family meetings can be a real scene,” says one Hunt associate. “Bunker says, ‘I know how it is: it’s like this.’ Margaret says ‘No, it’s like this.’ Herbert says, ‘No, it’s like Bunker says; I took notes.’ Lamar says, ‘Why do we always have to go through this?’ and Caroline doesn’t say anything.”) But none of the members of the first family are playboys or social drop-outs, and when it comes time to face the outside world, each submerges his differences into a solidly united front.

They have been particularly united in their dealings with the second and third families. For most of their early years, the children of the first family did not know about their father’s involvement with Frania Tye. Margaret, of course, found out in the thirties, and so did her mother, but Bunker and the others became aware only gradually. In fact, as late as the mid-fifties, long after they had gone to work at the Hunt Oil offices on a full-time basis, the three brothers still had not learned of their father’s extramarital relationship. Then one day Herbert came across an oil lease earmarked for the “Reliance Trusts.” When he asked his father about it, H. L. told him for whom it was intended. A short time later, the rest of the family found out, too.

Referred to simply as “the Lee people from Atlanta,” Frania and her brood became just another entry in the album of family secrets. In the late fifties Hugh Lee or one of the other children would occasionally show up at the Mount Vernon household, but in those days at least, the offspring got along fairly amicably. At one point, they even joined in a touch football game in the backyard.

As time passed, the first family began to develop a certain sense of humor about their father’s unknown heirs and pretended heirs. On one occasion, for example, a rather scraggly, long-haired young man came to Herbert’s office and presented himself as one of H. L.’s illegitimate offspring.

“Take off your socks,” Herbert instructed the surprised fellow. “I want to see your feet.”

Somewhat taken aback, the young man did as he had been told, and propped one leg up on Herbert’s desk.

“You don’t have it,” Herbert announced conclusively. “You can’t be who you say you are.”

“Don’t have what?” the young man asked.

“The Hunt toe,” Herbert replied, taking off his own shoes and socks to show him. “All the Hunts have little toes that curl under and in. It’s a genetic trait that comes from Dad.”

Sadly, the young pretender put on his shoes and socks and left.

News of Ruth Ray and her brood came about the same time as the discovery of the Lee people, but not nearly as easily. Although the existence of this so-called second family was known to at least one relative and a number of Hunt Oil employees almost from the beginning, the secret was kept with remarkable success. In fact, when Lamar was about to embark on his first marriage, he was still asking if it was true that his father had a family in East Dallas and another in predominantly black South Oak Cliff. He was assured that despite myths to the contrary, H. L. did not have a family in South Oak Cliff.

A short time later, Lyda Hunt’s health began to fail, and in 1955 she died of cancer.

All of a sudden, Ruth Ray began showing up at Mount Vernon, sometimes in the company of her children, who by then ranged in age from seven to twelve. Two years younger than H. L.’s daughter Margaret, Ruth would fuss over the old man and take it upon herself to look after the duties of the household. Having already lived through the Frania experience, it did not take long for the first family children to figure out what was happening. According to those close to them, their reactions to Ruth ranged from antipathy to benign indifference, but, knowing the strong-mindedness of their old man, they realized they were virtually powerless to stop his involvement with her.

Finally, in 1957, Ruth and H. L. were married. Hunt then adopted Ruth’s four children, changed their names from the fictitious “Wright” to Hunt, and sent them to new private schools. Three years later, with the help of Rev. W. A. Criswell of Dallas’ First Baptist Church, Ruth brought H. L. to religion, and had him enroll along with the rest of the second family in Criswell’s church. In an interview she gave later on, Ruth revealed what everyone who saw her children could tell by looking—that their real father was H. L. Hunt.

All this seems to have had a powerful effect on the sons and daughters of the first family. Although they would deny it in public, they clearly did not care for Ruth and certainly did not intend to treat her like a new mother. At their best, they regarded their half-brothers and half-sisters more like cousins than siblings; at their worst, according to those close to them, they regarded Ruth’s children as what they literally were. Obviously feeling somewhat displaced from their rightful position, the members of the first family drew closer together. If they did not feel they had to go out of their way to hurt the second family, they did not feel that they should go out of their way to help them, either.

For all the difficulties the first family faced, Ruth’s children had an even rougher time adjusting to their parents’ new relationship. Away on overseas trips much of the time, Ruth and H. L. left them in the care of a French governess and a black cook named Laura Grant. Laura would sing with the girls and entertain them with stories, and the governess would take responsibility for the rest of their care. The children were under a peculiar strain. On the one hand, they, like the children of the first family before them, had to prove to the world that they were more than just the children of H. L. Hunt. On the other, they had to show their half-brothers and half-sisters that they were bona fide Hunts, well worthy of the name. There is no question that they felt the strain. “There were times as a teenager when I would have given anything to have been in a normal family,” Swanee said recently.

Nevertheless, the children of the second family learned to adapt remarkably well. Seeing in their unique family situation a wealth of spiritual lessons equal to their father’s financial fortune, the three girls turned strongly to religion and the helping professions. June, a compassionate, large-bodied girl with her father’s hawk-like eyes and nose, became a professional gospel singer. A graduate of SMU, she also wrote a religious tract entitled Above All Else and preached—sometimes sharing a pulpit with Billy Graham—the necessity of treating others with what she called “unconditional love.” Unmarried, she continued to live with her mother on the Mount Vernon estate. Swanee, the youngest, attended Texas Christian, then married a Methodist minister of the new school. She and her husband eventually settled in Denver, Colorado, where they have been working to establish a “house church” serving the residents of the inner city. Helen, the second youngest, graduated from SMU, then taught school for a year at South Oak Cliff High School. Afterwards, she married an up-and-coming Dallas businessman named Randall Kreiling with whom she had two children. Short and attractive, she has a pleasant but slightly more worldly style than her sisters. She was recently divorced.

Of all the second family children, Ray seems to have had the easiest time on the outside but the roughest time on the inside. When his parents pulled him out of Greenhill School after their marriage, Ray entered Dallas’ more exclusive St. Mark’s School and compiled a longer list of student activities than anyone else in his class. He was editor of the newspaper, chief photographer for the yearbook, president of the band, and a member of the football and track teams. His senior year, he was elected class president, partly because of the efforts of a good friend and classmate whose life would take a vastly different turn from his own, future rock star Steve Miller.

“Ray was not the most popular guy in the class,” a longtime friend remembered later. “He was elected because we thought he could get the most done.”

One of the things he did was persuade his parents to let him hold the class party at Mount Vernon. Otherwise, Ray seldom traded on his last name. “He took a lot of kidding about it,” a St. Mark’s teacher recalled. “But Tom Landry’s son was in school at the same time, and he took more. Ray always did remarkably well handling himself about that.” In fact, the teacher said. Ray even wrote a skit for the class play in which he played himself. The second character in the skit was the son of a dishwasher, the third was an attractive girl. The dishwasher’s son was winning the girl until she asked his father’s occupation. Obviously disappointed, she asked Ray what his father did. When he announced that his father was H. L. Hunt, the famous oil billionaire, the girl walked off with him.

On the surface, Ray’s life seemed to imitate his prep school skit. He went on to graduate from SMU with a degree in economics, married a former college classmate with high school prom-queen looks and a kind disposition, then went to work down at Hunt Oil Company drilling oil wells with money from his trust fund. He also began raising a family of four children. While his half-brothers and half-sisters preferred residences in exclusive Highland Park, Ray and his wife settled into the anonymity of North Dallas and attempted to live a “normal” middle-class life.

Although he devoted 80 per cent of his time to overseas and domestic oil operations, Ray made his first major headlines by announcing plans for his first real estate venture: the $200 million Reunion Plaza, an ambitious downtown revitalization project. Reunion Plaza marked a break with two traditions. For one thing, it was the first major development project that featured the City of Dallas as a working partner with a private developer. For another, it was the first time a Hunt had done anything to promote the civic good. Ray further enhanced his civic image in 1974 by becoming the principal backer of D, a local version of the slick city magazines cropping up all over the country. Though both Reunion and D were conceived as profitmaking ventures, the overriding impression was that Ray had become involved with the two projects because he really cared about his city.

Before long, Ray began to get the kind of press that not even a Hunt could buy. In an article on the Hunts shortly after H. L.’s death, Business Week portrayed Ray as the young comer of Dallas and the new breath of sophistication in the family empire. Time, in a story last summer, called him “The Nice Hunt,” an appellation implying a contrast between Ray and his father and half-brothers.

More careful and conventional in every way than his half-brothers, he let his party politics remain indefinite, but surrounded himself with young Republicans. Were it not for his natural shyness, he would seem a perfect candidate for public office.

Part of that shyness proceeds from his family heritage. Ray sometimes told friends that he thought he had a lot of his old man in him, yet he also seemed to be the Hunt most insecure and ambivalent about being a Hunt, the one most anxious to prove that he would be worth knowing even if his last name did not have what he called that “peculiar spelling.” Not surprisingly, the hardest thing of all was getting along with his half-brothers.

“Bunker and his brothers just looked at Ray as different,” one insider recalled. “He made them feel uncomfortable and vice versa. They could never seem to accept each other as brothers. The three older ones always worked together, but they never brought Ray in with them. He was always the little guy. They always left him out in the cold.”

Another Hunt Oil executive remembered that Ray found it difficult to get interested in the company in his early years. “One summer they had him in leasing, but he didn’t show much enthusiasm about that,” the man said. “When he got out of college, he used to ask his relatives to let him sit in when they made an executive decision. The problem was that you just can’t plan ahead when you’re going to make executive decisions in the oil business, but Ray didn’t seem to grasp that. He also never quite seemed to be able to make it to the weekly production meetings they held in Tom Hunt’s office. Even old H. L. somehow managed to show up for those.”

The tensions of the office scene merely mirrored and exacerbated what was happening on the home front. As H. L. grew older and dottier, he turned increasingly to his right-wing political writings and grew fond of munching on nuts spread out on a newspaper and doing “creeping” exercises on the floor. With research assistance from daughter Margaret, Hunt also wrote Hunt Heritage, a book which mentioned neither Frania nor Ruth. Nevertheless, he seems to have spent more and more time with Ruth and less and less time with the children of the first family. An unpretentious woman more inclined to dimestores and double knits than to the Neiman-Marcus style, Ruth packed the brown-paperbag lunches H. L. took with him to the office, and organized group “sing-alongs” at Mount Vernon for family, friends, and favored employees. Jealousies increased and the two families grew even farther apart. If there never was much chance of the two treating each other as equals, it soon became clear that there was little hope of simple coexistence. Confident of their legitimacy and secure in their finances, the first family apparently saw the second replacing them in the hierarchy of their father’s affections. Increasingly sure of H. L.’s love, the second family apparently saw the first threatening to deprive them of their legitimacy as Hunts and of their rightful financial inheritance. A serious rupture seemed inevitable.

The inevitable began late in 1968. The key non-family actors were Hunt Oil security chief Paul M. Rothermel, Jr., an ex-FBI special agent, and Hunt Oil aides John Curington and John Brown. During H. L.’s waning years, Rothermel, Curington, and Brown had gained increasing personal influence with the old man. Curington and Brown also came to have responsibility for supervising Hunt’s food company division. Toward the end of 1968, unsubstantiated rumors began circulating among the first family that Rothermel and his friends were allied with Ruth in advising H. L. to leave the bulk of his estate to the second family. “When I arrived at the house on Christmas day, H. L. sounded so weak I thought he was doped up,” a friend of the first family recalled. “He said ‘They’re trying to get me to change the will.’ ” Although Ray later denied these rumors, the first family was not satisfied.

The plot thickened several months later in the summer of 1969 when cousin Tom Hunt got word of irregularities in the food company operations. Upon further investigation, he claimed to discover evidence of massive losses, and embezzlements later estimated at $50 million, and a trail leading right back to Rothermel, Curington, and Brown. Tom pleaded with his uncle to fire the three men or at least investigate them, as did all the children of the first family. But H. L. would not listen. As Ruth later testified, H. L. simply could not believe that such trusted advisors would betray him.

Bunker and Herbert were less naive. Although they had already received the bulk of their father’s choicest oil properties through their trust funds and looked to Hunt Oil only for general administrative and financial services, they felt they could not sit back and watch the rest of H. L.’s wealth get siphoned off. Determined to get to the bottom of the matter and frustrated with the official Hunt Oil Company investigation that finally did get underway, Bunker and Herbert decided to place wiretaps on the telephones of the suspected embezzlers and several other Hunt employees. But before ordering the wiretaps, they first went to their half-brother Ray and asked for his cooperation. The first family’s side of the story is that Ray not only refused to participate in the wiretapping, but also refused to investigate the alleged embezzlement at all. The way Ray’s associates tell it, Ray simply informed his half-brothers he would confine his efforts to the official Hunt Oil investigation. In any case, Bunker and Herbert were furious. Already somewhat estranged from Ray and his side of the family, they no longer saw any hope of bridging the deepening chasm between them. In a huff, they decided to proceed without his help.

After some initial frustrations, Bunker and Herbert claimed later, the wiretaps began to confirm their suspicions. Then, in January of 1970, a local policeman arrested one of the wiretappers for running a stop sign. When the young man panicked, the police discovered the electronic surveillance equipment he was carrying in his car. What followed was a story of plot, counterplot, intrigue, and betrayal worthy of the spy novelist, John Le Carré.

As the authorities pressured the wiretappers to reveal the reasons for the taps and the people who paid them, Bunker and Herbert agreed to pay the wiretappers’ attorneys’ fees and provide them with $800–$ 1250 monthly incomes if and when they went to prison. After the wiretappers were convicted, Bunker passed $100,000 through Houston industrialist E. J. Hudson to noted Houston attorney Percy Foreman, who was by then representing one of the wiretappers. The exact reasons and circumstances of these payments are subject to continuing legal dispute, but there is no dispute that the payments were made. After a three-year delay the lid of silence blew off. Claiming the Hunt brothers were making them suffer unnecessarily, the wiretappers finally told their story, and named Bunker and Herbert as their paymasters.

Meanwhile H. L. came to believe that an embezzlement had occurred and, thinking he had been betrayed, agreed to have Hunt Oil Company lawyers file civil damage suits against Rothermel, Curington, and Brown. Rothermel’s wife, in turn, filed suits against Bunker and Herbert for invading her privacy by wiretapping the family telephones. Soon allegations of political bribes and CIA deals began to surface in the press. Bunker and Herbert later claimed they negotiated a deal to drop their suits against Rothermel in return for which the government would drop its suits against the Hunts for wiretapping. However, either unaware of or uncommitted to any such deal, the Justice Department proceeded to indict the Hunt brothers for wiretapping. The government also indicted Bunker and Herbert, Foreman, Hudson, and several prominent Dallas attorneys for obstruction of justice. Bunker and Herbert claimed later that the CIA was behind the government’s “betrayal” of them, most likely out of resentment of the Hunts’ refusal to let the CIA place an agent in the Hunts’ operations in Libya a few years before.

Despite possessing tapes of the wiretaps, which the Hunts claimed proved their allegations about the embezzlements, the government moved even more slowly against Rothermel, Curington, and Brown. Finally, in 1974, after a grand jury investigation and repeated complaints by Hunt attorneys, the Justice Department decided to prosecute Curington and Brown. Rothermel, however, was granted immunity from prosecution for his testimony before the grand jury and was not indicted. Just how incriminating Rothermel’s testimony may have been was never determined, because Rothermel was never called to the witness stand in Curington and Brown’s subsequent trial. Later, after obtaining some heavily censored Freedom of Information act files on Rothermel, the Hunts alleged that he had been granted special treatment because he was a government agent, most likely with the CIA. Claiming he and the Hunts had signed a 1971 settlement agreement not to discuss each other publicly, Rothermel later denied any wrongdoing, but refused to comment on his possible CIA connections. Although he at one point acknowledged using his “influence on Mr. Hunt” to get H. L. to change his will in favor of the second family, Rothermel now refuses to comment on the subject of the will.