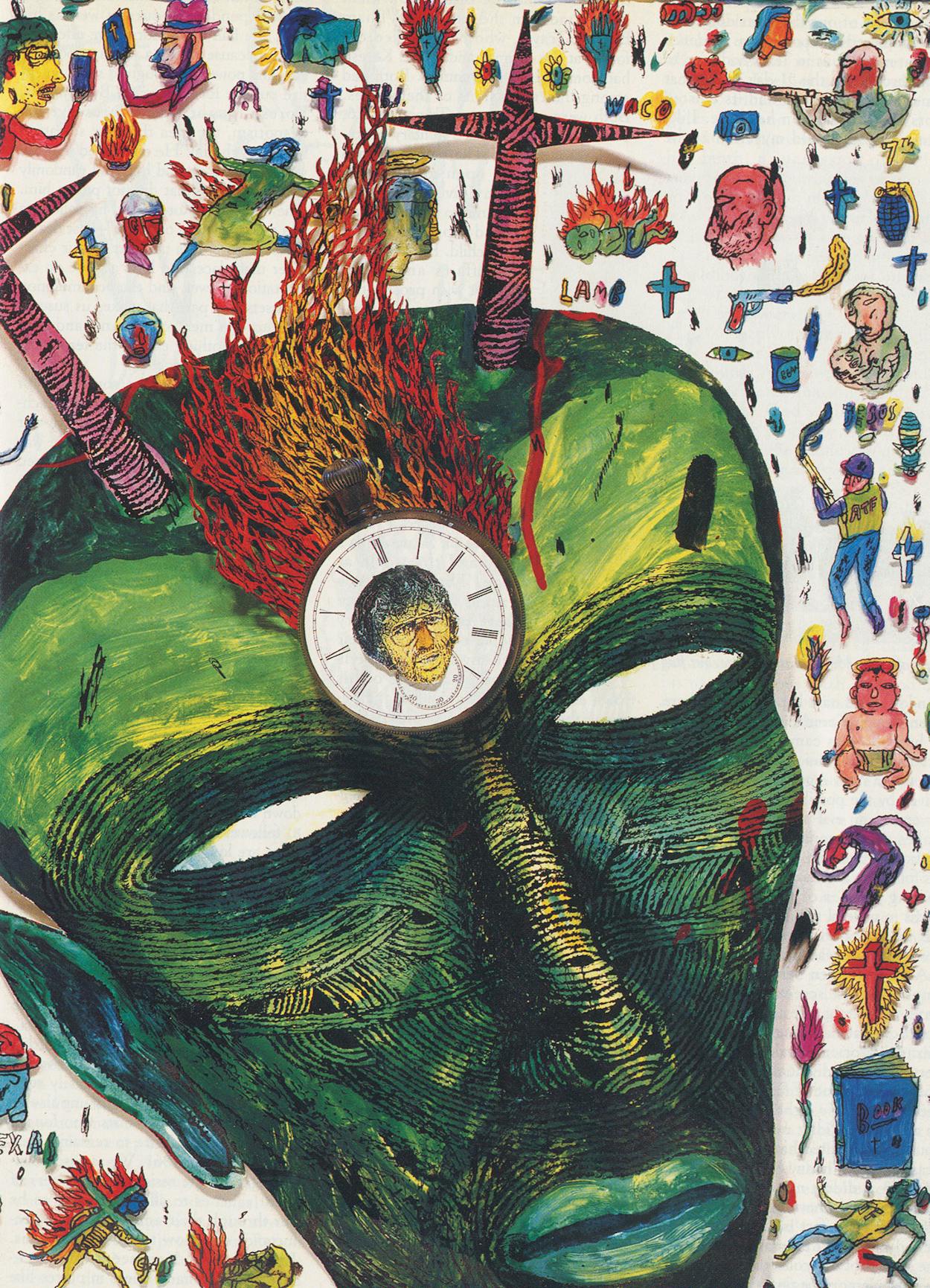

One day it was the star of David flag that snapped in the wind over David Koresh’s compound near Waco. The next day, after at least 86 people, including 17 children, had gone up in smoke, it was our own flag, Texas’ Lone Star, that flew at half-mast above the Ranch Apocalypse.

The sight of our flag presiding over the conquered compound was evidence of what many of us in Texas had tried to deny throughout the 51-day siege—that somehow this tragedy had its twisted roots on our common heritage. Like many people, I told myself that the standoff could have happened anywhere. Even though Koresh was a Texan, many of his followers came from Australia, Britain, and Hawaii. I took solace in the fact that a New Age religious sect—also driven by the possibility of an apocalyptic end to an evil world—has put down stakes in Montana, near Yellow Stone National Park. Jim Jones retreated with his followers and deadly Kool-Aid to the rotting jungles of Guyana. Neither Texas in general nor Waco in particular has the sole franchise on fervent, bellicose, religious wackos.

And yet hidden behind the wisps of smoke and the screen of death in the days following the inferno was the conflict that has long contributed to Texas’ historical burden—the conflict between the individual’s right to mete out his own brand of frontier justice and the community’s right to live in peace. In the end, it didn’t matter that Koresh could have isolated himself on a distant prairie outpost in any other state, just as in 1963 it didn’t matter that John F. Kennedy could have been assassinated anywhere. The fact is, both events happened here, and they are now part of the sorrow of our collective memory.

That memory begins with and is still dominated by the Alamo. Unfortunately there are comparisons between the Alamo and the Branch Dividian compound. On the surface, William Barrett Travis, who commanded the forces at the Alamo, and David Koresh had some things in common. Both had strong internal visions of themselves. Both were young men—Travis was 26, Koresh was 33—who led military operations. The morals of each were open to question. When Travis moved from Alabama to Texas, he left behind a pregnant wife and a child. He had many love affairs and found comfort with prostitutes; at least once he contracted a venereal disease. Koresh’s sexual predilections—his multiple partners, his pedophilia, his physical abuse—are by now well known.

Yet when Travis wrote “Victory or Death” from behind the barricades of the Alamo mission in 1836, he forced a vision of Texas on Santa Anna’s army and the world at large. That vision saw Texas as the kind of place where raw and ordinary people could invent their own mythology. Travis acted on a stage of his own creation, and that self-image became the central truth that still defines us. All truth is subjective, however, and what is no doubt valid on one sense is tragically wrong in another.

What David Koresh reveals is the negative side of the Alamo: the anti-Alamo. Viewed narrowly, Koresh seems a man of his region—the archetypal Texan. He isolated himself in a compound that he called a ranch. He hoisted his own flag. He paid good money for a private arsenal and vowed publicly to shoot the first son of a bitch who stepped onto his property. If you drive down any back road in Texas, you will see picturesque ranches whose owners have survived in good years and bad by playing precisely by those rules of the frontier.

This is hardly abnormal behavior in Texas, a fact that was not lost on the crowd of protestors who demonstrated regularly during the standoff on behalf of Koresh’s Second Amendment right to bear arms. To these protestors and others, the siege at Mount Carmel was the Alamo all over again, with Koresh as Travis and federal law enforcement agents—and by extension, the entire U.S. government—as the oppressors.

But there is something wrong with that picture. The difference between Travis and Koresh is not an outer distinction but an inner one. Travis fought for independence—ours as well as his own. He had a transformative effect on Texas because his idea was a good one, vital and powerful enough to serve an entire culture for 157 years. By contrast, Koresh fought only to preserve his despotism, the idea that our salvation was through him. He demanded that the world revolve around him and randomly destroyed ideas that did not please him. The choice for Koresh and his followers was never “victory or death”—just death. Koresh represents the part of our character that places too high a value on exploitation, power, and the accumulation of assets, the part that makes us susceptible to con men, charlatans, and liars who offer nothing except the ferociousness of their own egos.

David Koresh was a personification of the Texas pseudo-hero, revealing treacherous strains that operated beneath our common life. He was violent. He was anti-intellectual. He greedily helped himself to other men’s wives, and he treated his children as objects of his own glorification. On the Texas frontier—the terrain that is the source for so many of our shared legends—women kept the home and took care of the men and the livestock. But they had the freedom to become tough and independent. On Koresh’s ranch, women and children were first captives, then fodder for a fiery slaughter that accrued no benefits to anyone. Even worse, Koresh presumed the greatest possible vanity; He called himself the Son of God.

The image of Koresh that haunts me is one that has been shown repeatedly on television. He is pacing up and down in a nondescript room, preaching to followers seated on metal risers. His jeans are low on his hips, and the tail of his unironed shirt is flying free. In his left hand, he is waving an open Bible. On the TV tape, Koresh is fully revealed for what he was: a high school dropout who knew he couldn’t make it on the outside world; so he instead created a paradise where the only standards he had to adhere to were the shabby ones of his own making.

This is a second aspect of the burden of our collective memory: the drive for independence that can so easily turn into isolation. We saw this impulse at work in those secessionists who fought Sam Houston’s desire to remain a part of the Union in 1861. We saw isolationism again in the resistance of owners of great ranches to allow highways to be cut through their empires, and the reluctance even now to cross fence lines. In modern times we see it in the tendency toward narrowness in places like San Antonio, where older families continue to oppose the inevitable presence of outsiders.

Growing up in East Texas, I first recognized why people like David Koresh can become so discontented that they retreat to insular worlds of their own creation. In the Big Thicket, the operative stereotype was not Edna Ferber’s Giant. I have few memories of seeing a horizon, much less a Longhorn or a range, until I was a teenager. The Texas of my childhood was poor, ignorant, and mistrustful of everything big: big business, big government, big ideas. The worst thing you could say to anyone was “You’re gettin’ too big for your britches,” which I later understood to mean, “I can no longer control you.”

Instead of oil derricks or towering skyscrapers—signs of prosperity—I grew up surrounded by a pine forest that was thick and dark, and the most visible evidence of bounty were roadside stands heaped with tomatoes, cucumbers, yellow squash, peas, and lovely melons. Churches were places of pleasant retreat. Nonetheless, I have sat in many a back pew in East Texas and felt like a heretic because I have a real and terrible hunger for books other than the Bible. In the Texas that gave birth to both Koresh and me, knowledge of the outside world is not just a weakness but a sin. Some find freedom from the “secular” world by retreating to the pure isolation of the Bible. Often I have wondered what feeds this physical and emotional insularity, and the only answers I have found are the stubborn resistance to change and the fear of the passage of time. It is that resistance that causes many Texans to live veiled, cultish lives and drives others to seek relief by becoming expatriates. When the national economy fails or there is trouble abroad, you can always count on seeing a new crop of “Secede” bumper stickers spring up on our highways. It’s also the reason that many Texans will move all the way to New York City and then seek out an uptown bar called the Lone Star Cafe Roadhouse.

There is nothing wrong with separatism as long as the reason for it is to build something concrete: a business, a family, a church, a university, a work of art. But when those among us retreat in fear to do battle with the outside world, they are not real ranchers, but pretend ranchers, sucking off the past in search of an identity. They are not living out the myth of the Alamo, but the anti-Alamo. It’s no accident that our flags casts its shadow on the ruins of Ranch Apocalypse, because what the ranch represents is our shadow side, the part of us that cannot face the irrevocability of all that has been lost.

- More About:

- Texas History

- David Koresh

- Waco