This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

When Texas Ranger Bobby Paul Doherty looked out of his kitchen window and saw patches of snow, he thought about the firewood he hadn’t cut on Sunday. He had promised his wife, Carolyn, that he and Buster would do it right after church, but there had been a meeting of deacons, then the telephone call from the Denton sheriff’s office saying the drug raid was set for that afternoon. Sunday had been a day of prolonged frustration. The drug raid hadn’t gone down after all. He didn’t know why. That’s the way it was with dope dealers. You could work for days or weeks setting it up, then the whole show could fold at the whim of a dealer or the duplicity of an informant.

There was only one thing in this world that Ranger Bob Doherty hated worse than dope and that was dope dealers. He was a fanatic on the subject. “They call us Mr. and Mrs. Redneck,” Carolyn had joked to friends. Carolyn certainly did not approve of drugs but she was not vehement about the long hair and beards and weird lifestyles that her husband automatically associated with major crime. “In his line of work,” she said, “he had to think that way.” Even out in Azle where they made their home, well away from the degenerate streets of Fort Worth where a school kid could score a lid of grass as easily as he could buy a soda pop, drugs occupied an alarming share of school-yard conversations.

All that talk about victimless crimes made Bob Doherty sick. Someone always got hurt, someone other than the person using the drugs. “You ask them if they think drugs are a victimless crime!” he had told his seventeen-year-old daughter, Kelly, on the morning that she was to attend a high school assembly conducted by three former addicts. The Ranger had told his sixteen-year-old son, Buster, about the time, only a few months before, when he had kicked in the door of a gambling den, crashed through a hole in the floor, and landed dead center on a homemade bomb placed there to destroy evidence in the event of just such a raid. If the bomb had exploded, the entire Doherty family would have been its victims. Only a lawman knew what it was like below the surface of the drug culture. It was like his old friend Dwight Crawford, captain of criminal investigation for the Denton County Sheriff’s Department, had said so often: “Bob, it’s a sewer down there. Dark tunnels leading off in ever’ what direction.” That’s why they had all been so frustrated on Sunday. They had an opportunity to explore a few of those tunnels, but someone slammed the door too soon.

Now it was Monday, February 20. It was the official state holiday for Washington’s Birthday, but for Ranger Doherty it was just another morning for wondering if he would ever find time to cut the firewood. This was no mere ceremonial task like trimming the Christmas tree or painting the porch. Their house was heated entirely by wood-burning fireplaces. Bob and Carolyn Doherty had built their handsome white brick home on an isolated three-and-a-half-acre plot that had been part of her daddy’s dairy, and though it contained many modern conveniences, the center of their family life was the den with its large fireplace. The den was the Ranger’s favorite room, the place he kept his collection of handguns and the antique rifle that was supposed to have been used by one of General Custer’s troopers. The stone fireplace reminded Bob Doherty of times past, times he had only read about: when old-time Texas Rangers lived on parched corn, jerky, and brackish coffee, freezing on some desolate plateau and ranging hundreds of miles alone on horseback to protect life and property from Indians, Mexican bandits, and other desperadoes. The Ranger had told Carolyn on many occasions: “Honey, I think I was born a hundred years too late.” But he was still a Texas Ranger, and it was far and away the proudest fact of his life.

It was not yet 8 a.m. when Captain Dwight Crawford telephoned from Denton. “Mary Nosser claims Baker tried to kill her last night,” he said, while Bob Doherty listened without comment. “Says Baker tried to overdose her with some heroin mixed in a Coca-Cola. Sounded like they had some party.”

“It wasn’t the crime that obsessed the officers that night; it was the chase, the irresistible urge to play cops and robbers.”

Bob Doherty hung up and grabbed his white Stetson. Carolyn met him at the front door with his briefcase. Everything else he would need was in the trunk of his car. “I’ll be home as soon as I can,” Doherty told his wife. In the eighteen months that he had been a Ranger, Doherty had told his wife good-bye every morning with almost the same words, and Carolyn seldom asked the question that was on her mind—when did he intend to slow down? It had been four years since their last vacation and almost two years since his last full day off. “The kids and I weren’t jealous of his job, but we were jealous of his time,” she would admit later. “But Bob wanted to be a working Ranger, and we knew he would slow down when he felt he was able.” The only times Doherty’s family could be certain he would be with them was when Buster’s Azle High School team played football. The Ranger, who had been a football player himself, never missed a game.

Carolyn stood on the porch under the graceful Spanish arches and watched as her husband strode through the patches of snow to his car. The arches had been his idea. Someday, he had said, he would hang a hammock here and watch the sun do its work. She suddenly remembered something. “Remember the deacons’ meeting at the church tonight,” she called out. “I’ll try to make it,” he said. She watched him turn his car and head out the driveway.

On his way to Denton, Bob Doherty thought about Mary Nosser. If Jimmy Baker really had tried to kill her, then it was likely that the whole deal was off. The Ranger and Dwight Crawford had been working for weeks to land Jimmy Baker; Nosser was their bait. The case had developed when Nosser’s boyfriend, Kenneth Ray Bunyard, called Dwight Crawford to his cell in the Denton County jail and suggested a deal. Bunyard and Baker had once been partners in a drug operation, but they fell out and Bunyard was later arrested and charged with stealing cocaine from a local hospital. In return for certain considerations that were never made public, Bunyard fingered Jimmy Baker as “a heavy dealer of marijuana, cocaine, and speed in the Gainesville-Denton area.” Since Baker didn’t live in Denton County, Crawford asked Ranger Bob Doherty for assistance. A big part of a Ranger’s job is to assist local law enforcement agencies, especially in cases where more than one county is involved. Mary Nosser agreed to set up Baker for a marijuana buy, but they also would need an undercover agent to act as the customer. Ranger Doherty telephoned DPS Narcotics in Austin, and agent Ben Neel was dispatched to Denton on special assignment. Neel, a shaggy-haired 41-year-old agent who looked like an aging hippie, posed as “Steve McCloud,” an ex-mafioso heroin dealer from Saint Louis. Nosser had already convinced Baker and his wife, Linda, that “McCloud” was a trusted contact from her own days of street dealing in Saint Louis, and Baker had agreed to sell him fifty pounds of grass. The shipment had arrived over the weekend, but Baker and some of his friends, including Mary Nosser, had decided they would rather party than work, so the meeting with “McCloud” never took place. Maybe Baker had seen the setup and really had tried to kill Nosser, or maybe in the paranoia of the heroin party Nosser just thought so. Either way, it could jeopardize weeks of undercover work. This was a side of Bob Doherty’s job that the public never understood and that made it even more frustrating. The Ranger knew about those dark tunnels that Dwight Crawford described. He knew that without a few breaks they went nowhere.

The break came late Monday afternoon. Apparently the episode with the heroin hadn’t been serious, because Mary Nosser called Captain Crawford and said, “He’s ready to do the deal tonight.”

They moved into action. Crawford arranged for two rooms at the local Ramada Inn, room 154 for “Steve McCloud” and room 155 for his raiding party of cops. By the time Mary Nosser delivered Jimmy and Linda Baker to room 154, the trap was set. Agent Ben Neel, posing as the dealer from Saint Louis, was alone when he opened the door, but listening at the unlocked door of the adjacent room were four heavily armed lawmen—Ranger Bob Doherty, Captain Dwight Crawford, and two of Crawford’s deputies, Bailey Gilliland and Ron “Tracker” Douglas. From the opening conversation, Doherty and Crawford could tell that things were not going as planned. Baker had agreed to bring fifty pounds of marijuana but showed up with only one pound. “I thought you’d want to taste it first,” he told Neel. Neel would testify later that he “simulated” smoking the grass, then gave his approval. Baker telephoned a friend, Joe Fultner, who was supposed to bring the remaining 49 pounds. Neel sent out for beer, and while they waited for the full shipment they drank, passed joints, and listened to Neel’s concocted tales about his Mafia and heroin-dealing days in Saint Louis. When Joe Fultner arrived about an hour later, Doherty, Crawford, and the two deputies burst into the room and made the arrests.

Crawford took charge of the sack that Fultner had delivered. “There’s only nineteen pounds here,” he said—twenty counting the sample Baker brought. Baker told them that was all he could get.

There are two versions of what happened next. According to Ben Neel: “I told Mr. Baker that if he would assist us in going ahead with the entire fifty pounds . . . in other words, by getting the remaining thirty pounds . . . I would advise the district attorney that he cooperated.” Baker then told the lawmen that he had a friend named Greg who lived in the country and might be able to fill the order. But Jimmy Baker’s version was different: “It was already known that I was going to get the next shipment from Greg and they already knew it and they knew where his house was and it was just a matter of time. They were going out there anyway.” Linda Baker added one more detail. She said: “One of them told Jimmy that if he didn’t cooperate, he wouldn’t ever get to jail alive.” All parties agreed that Baker then telephoned Greg Ott, a 27-year-old honor graduate student at North Texas State University, and arranged to bring his pal “Steve” to Ott’s place in the country later that night.

While Dwight Crawford returned to town to book Linda Baker and Fultner and to secure another $1400 in “buy” money, Neel and the deputies finished the beer and planned the raid. To Ranger Doherty it was like a military operation, but deputies Gilliland and Douglas looked on it more as a possum hunt. They gave the impression they had been waiting a long time for some real action. Sometime before Crawford returned with the buy money, DPS narcotics agent Don Jones joined the party at the Ramada Inn. Jones apparently wasn’t expecting a raid because he didn’t bring a gun. Neel loaned him one.

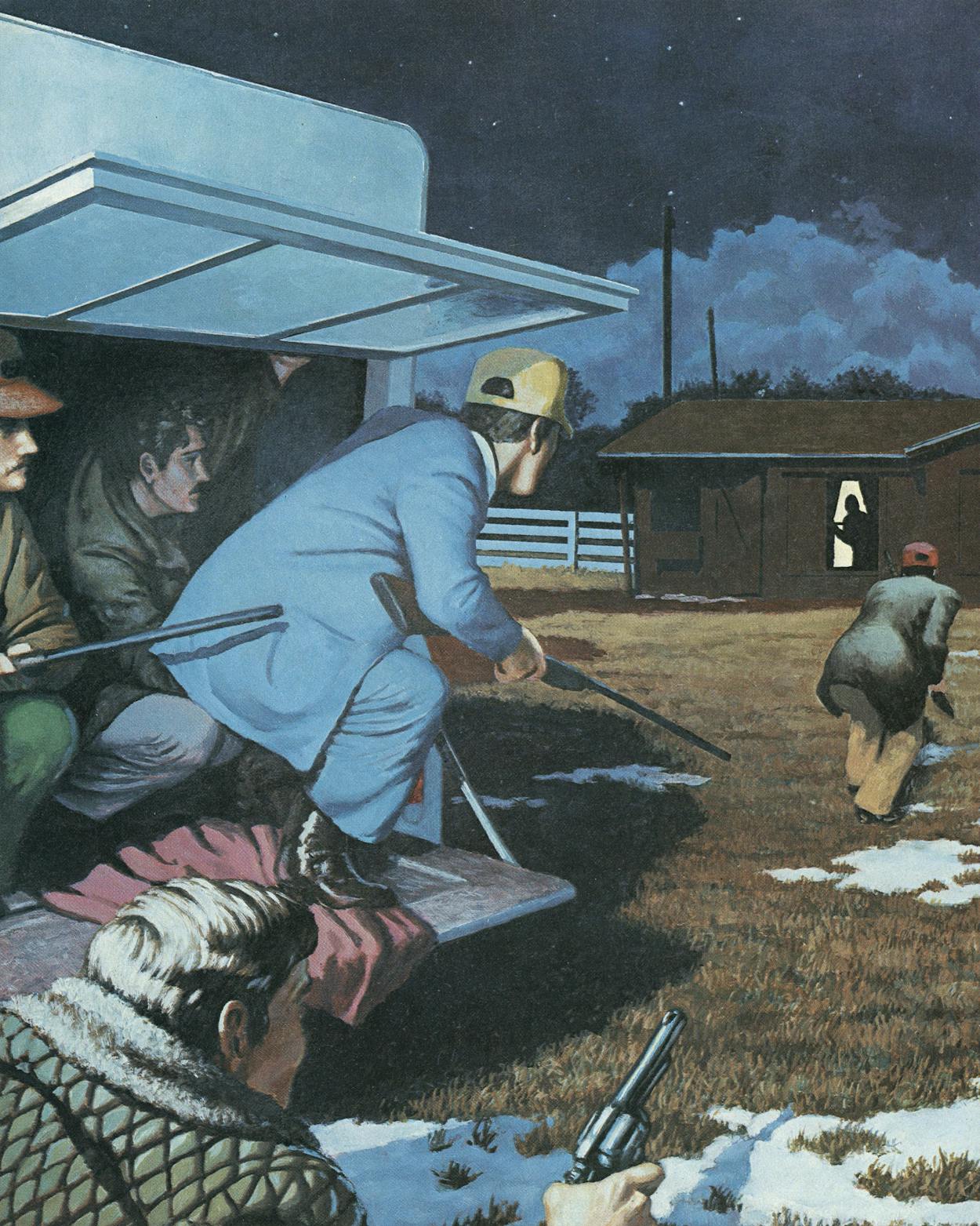

It was about 11 p.m. when a pickup truck with a camper on the back turned off Hickory Hill Road, near the tiny Denton County community of Argyle, and headed up the long, curving blacktop of Twin Pines Ranch. The ranch was primarily a place where wealthy girls stabled their horses and took riding lessons, but there were several rent houses on the property, including the small frame structure where Greg Ott had lived for about four years. Jimmy Baker, who was now in the uncomfortable role of informant, rode in the cab with Ben Neel. Hiding under a blanket in the camper were Ranger Bob Doherty, Captain Dwight Crawford, agent Don Jones, and the two deputies. None of them were wearing uniforms, although Crawford had a Denton County Sheriff’s Department emblem on either shoulder of his quilted, fur-collared jacket. Bob Doherty still wore the brown Western-cut jacket he had put on before he left home, but he had replaced his Texas Ranger Stetson with a red baseball cap and, according to the testimony of the other officers, now displayed his Ranger badge over his left chest pocket. Even in the light of a nearly full moon the five men must have looked more like duck hunters than lawmen.

Jimmy Baker had told them that Ott kept his goods in the barn behind the house. Agent Neel, the expert in these matters, formulated this plan: Baker would take Neel inside and introduce him as “Steve McCloud” (Neel even carried an out-of-state driver’s license issued in that name), and they would begin negotiating a deal. Neel would accompany Ott to the barn, and, when they returned to the house with the marijuana, Neel would leave the kitchen door open as a signal for the raid to commence. Things went as planned up to that point.

What happened in the next ten to fifteen seconds could have passed for a Keystone Kops comedy if it hadn’t ended so tragically. As Ranger Doherty was leading the raiding party out of the back of the camper, the swing-up overhead door dropped and hit him on the back, rendering into the crisp winter night a dreadful noise. The Ranger grabbed his shotgun and ran toward the southwest corner of the house. Dwight Crawford, the second man out, followed Doherty. Crawford would testify later that as he ran along the edge of the house he twice shouted, “Police officers!” Agent Don Jones was the third man on the ground, and he ran straight toward the door that Neel had left open, the door leading to the kitchen. Deputies Bailey Gilliland and Tracker Douglas got tangled in the blanket and were slow getting out of the camper. Tracker, who got his nickname because of his distinctive Indian features, would testify that as he was climbing down he glanced at the kitchen door and saw the figure of a man. “I told Bailey to be real careful, somebody was gonna get blowed away,” he recalled. Both deputies would testify that they heard unidentified voices inside holler, “Drop the gun or I’ll kill you!” and “He’s got a gun!” followed by two gunshots several seconds apart.

“For Greg Ott it must have been a terrifying sight: five heavily armed strangers in hunter’s clothes climbing from the rear of a camper.”

Ben Neel, Greg Ott, and Jimmy Baker were in the back bedroom examining the marijuana when they heard the noise of the camper door falling. Neel testified that Ott hurried to the kitchen door and looked out. From Ott’s point of view it must have been a terrifying sight: five heavily armed strangers in hunters’ clothes climbing from the rear of a camper. Ott ran back through the middle room and toward the beaded curtains leading to the living room, passing very close to the bedroom door where Neel was still standing. Ott had a pistol in his hand, and by now Neel had drawn his own .45. Neel testified: “I stepped out into the doorway of the bedroom and I hollered in a real loud voice just right in his face, ‘Police officer! Drop the gun!’ He . . . started toward the doorway [to the living room]. . . . Again I yelled, ‘Police officer! Freeze!’ ”

Just as Ott was about to disappear through the beaded curtains and into the living room, Neel fired at Ott and missed. Ott, gun in hand, was headed toward the living room door at the northwest corner of the house.

Outside the northwest corner of the house, Ranger Doherty and Deputy Gilliland heard Neel’s shot. Gilliland leaned across a pile of firewood and tried to see through a window curtain. Ranger Doherty positioned himself directly in front of the living room door, crouched slightly, and kicked it open. At the exact second that the Ranger’s boot smashed into the door, a bullet fired from inside the house passed through the door and hit him above the right eye. Bob Doherty fell straight back, staining the snow with blood. He never saw the man who killed him.

Telephone calls in the middle of the night never bothered Carolyn Doherty. But for twenty years she had lived with the dread of a knock at the door. “I knew if I heard a knock in the middle of the night and I opened the door and a lieutenant or sergeant was standing there . . . I knew Bob would be dead.” But on the night of February 20, there was no time for official courtesy. Bob Doherty was unconscious but still showed vital signs as the ambulance raced from Denton to John Peter Smith Hospital in Fort Worth, escorted by maybe a dozen police units sealing off traffic in every direction. Police radios all over North Texas crackled like leaves in a storm.

It was sometime after 11 p.m. when Carolyn Doherty answered the phone. Ranger Tom Arnold, calling from Arlington, told her, “Carolyn, I hate to tell you, but Bob’s been hurt.”

“How?” she asked.

“Gunshot,” Arnold said.

She didn’t want to ask the next question, but she had to. “Where?”

“In the head region,” Arnold said.

He said he was coming to get her, but Carolyn told him there was no time. She hung up, amazed at her own calm. She telephoned her preacher, Jesse Leonard; then her mother, who lived next door; then Charlie Stewart, chief of the Azle Police Department. The calls had awakened Kelly. “Your daddy’s been shot,” Carolyn told her daughter. “Don’t wake Buster till we see how bad it is.” Carolyn’s father arrived from next door to stay with the children. In a matter of minutes Carolyn, her mother, and the preacher were passengers in Chief Stewart’s police car, screaming toward the hospital in Fort Worth. At every traffic light there was a city or county or state police vehicle sealing off traffic. Nobody but another policeman could understand, Carolyn thought to herself. It’s a brotherhood. The crackling of the police radio gave her a block by block account of her husband’s race against death.

Carolyn is a large woman with a gentle face and, by her own admission, could “cry at the drop of a pin.” But no one this night would see her tears. All the way to the hospital, all she could think was: Isn’t it odd how things turn out. Carolyn and Bobby Paul Doherty had been sweethearts since they first met in the early fifties at Lake Worth High School, not more than a mile from where they lived now, and yet they had come so far. Bob Doherty was an all-around athlete in high school, good enough to win a football scholarship to Lamar Tech in Beaumont. He lasted only that first year. She remembered: “Beaumont was a long way from Lake Worth. He tried it, but after a while he came home to be close to me.” Even in high school Doherty had talked about becoming a Texas Ranger. But that seemed an impossible distance from where they were when they got married in 1957. Maybe if he had stayed in college. But things turn out. Doherty worked for a while at General Dynamics in Fort Worth and served as a volunteer fireman and reserve police officer in Lake Worth, all the time waiting for word on his DPS application. Today it takes a minimum of sixty college hours for an applicant to be admitted to the Department of Public Safety Academy, but in those days it was easier, and she remembered their jubilation when he was finally accepted in 1958. “We didn’t have much money then,” she recalled, “and yet things were so good that sometimes it scared me.”

For his first five years as a DPS trooper, Doherty was stationed in Wharton. Carolyn recalled how happy she had been when she heard they were transferring to Gainesville, much closer to home, but now there was a lump in her throat as she remembered how the vacancy came about—a DPS trooper had been shot to death. In 1969 they were transferred to Fort Worth and built their home in Azle. Even then she had mixed feelings. Doherty had already decided to apply for the Rangers, and Carolyn knew that when he was accepted he would likely be stationed in another part of the state. Both children were established in school now—Kelly was an honor student, and Buster a promising young middle guard on the football team. It would be very hard to move again. Sitting in the front seat of Charlie Stewart’s police car, Carolyn almost cried when she recalled that day in 1976 when Bob suddenly asked: “If you could have two wishes, what would they be?” She had answered immediately: “For you to get promoted to the Rangers, and for us to stay here.” Bob had smiled and told her: “You guessed it.” Bob’s career prospered, and they settled into their house. So things turn out, but in such odd ways.

Charlie Stewart’s police car arrived at John Peter Smith Hospital just ahead of the ambulance. Carolyn waited at the emergency room door. “My first thought,” she said later, “was, Lord, don’t let it be serious. Then I saw them bringing Bob in and I knew it was too late. My next thought was, Lord, give me strength to accept what will be.” By now the emergency room was swarming with every variety of cop. It was only a few minutes before Ranger Captain G. W. Burks, Doherty’s commanding officer, took her aside and said, “Carolyn, he’s gone.”

“It’s funny the things you think to say at a moment like that,” she recalled. “I asked if Bob had ever been conscious. He said no. That’s what I wanted to hear. I asked if they got the man who did it. He said yes.” Someone gave her Bob’s briefcase. She almost felt like a trespasser opening it. The briefcase contained a number of unanswered letters postmarked from all over the state. One was a note from Roy D. Tavender of Texas Refinery Corporation thanking the Ranger “for signing all those Gunslinger Awards.” Taped to the inside lid of the briefcase was a card titled “The Ranger’s Prayer.” At the top of the card was a picture of a machine gun. Carolyn’s mother was crying, and the preacher looked like he was experiencing Judgment Day, but Carolyn Doherty was thinking, I’m glad he didn’t get killed going to the grocery store. He hated to go to the grocery store.

When Carolyn picked up the newspaper the following morning, there, staring at her, was a picture of the accused killer, Greg Ott. His hands were cuffed across his chest and through the wild nest of long, black hair and scrubby beard, his eyes burned with a terrible light. It was impossible to look at the picture without thinking Charles Manson. How strange, Carolyn thought; she felt no bitterness, no hatred, just a permanent sense of loss. But she said to herself: This man is everything Bob was against.

No one in Fort Worth could recall a funeral quite like Bob Doherty’s. The Lakeside Baptist Church where he was a deacon was too small, so the service was held at the Rosen Heights Baptist Church. A crowd estimated at 2000 filled the church and its auxiliary chapel. Hundreds more waited outside. Letters and flowers and telegrams came from all over the world. Dolph Briscoe was expected but didn’t show. Attorney General John Hill was in prominent attendance. DPS Director Colonel Wilson Speir was there, as was the largest gathering of Texas Rangers anyone had seen since the dedication of the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame in Waco. Outside the church about 350 uniformed lawmen, representing departments as far away as Texarkana and Houston, lined the parking lot in an honor guard. It had been 47 years since anyone had killed a Texas Ranger in the line of duty.

Forty miles north of Fort Worth, in the quiet college town of Denton, Greg Ott was being charged with capital murder and held without bond. Ott’s face was badly swollen and his ribs were bruised. He had been handcuffed facedown on the floor when Bailey Gilliland jerked him up by the hair and held him for Tracker Douglas, who said, “You won’t forget this Indian!” and smashed Ott between the eyes with his fist.

The folktale of “one riot, one Ranger,” is the perfect example of the Ranger legend, because it probably never happened. Like their nearest counterparts, the Canadian North West Mounted Police, the Texas Rangers were too wild and improbable for most history books, so their exploits had to be reconstituted for general consumption. So mystical is this branch of law enforcement that when a woman friend of mine read that a Texas Ranger had been killed she automatically assumed he was a baseball player. The “one riot, one Ranger” parable apparently refers to an incident in 1906 when Captain Bill McDonald faced down a group of twenty black U.S. Army soldiers at Fort Brown. But what McDonald said on another occasion probably speaks more accurately of the Ranger mentality, past and present: “No man in the wrong can stand up against a fellow that’s in the right and keeps on a-coming.”

The museum at the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame in Waco commemorates the legacy of violence and celebrates the myth of “the fellow that’s in the right and keeps on a-coming.” Almost all the museum exhibits are firearms once wielded by famous lawmen or equally famous outlaws. There are a number of guns used by famous Rangers like Lone Wolf Gonzaullas, Frank Hamer, A. Y. Allee, and Bill Wilson, along with Clyde Barrow’s Colt revolver and Bonnie Parker’s sawed-off shotgun. The curator of the museum has asked Mrs. Doherty for her husband’s .45; he hasn’t yet requested Greg Ott’s .38, but it is not unreasonable to think that someday he might. Some of the exhibits have nothing specifically to do with the Texas Rangers, but they do glorify the code and legend of the West, of which the Rangers no doubt consider themselves the custodians.

There was hardly any law in Texas when Stephen F. Austin created the Rangers in 1823, so the Rangers made their own. Their mission was to protect the lives and property of Anglo settlers and businessmen against Indians and other renegades unsympathetic to the white man’s ways, and legal disputes were often as not settled on the spot with a Colt revolver. An anonymous outlaw once remarked to old-time Ranger W. M. Green, “It is easy to see a graveyard in the muzzle of a Ranger’s gun.” Back around 1880, in an operation that became known as the “Red Tide,” a Ranger sergeant working undercover took crude photographs of outlaws and might-be outlaws along the border, then dispatched fifteen Rangers to “remove from circulation” anyone resembling the men in the snapshots. In a few weeks some one hundred “outlaws” were buzzard food.

In the early days the Rangers were a military organization, but one with a special mission. Walter Prescott Webb wrote: “The Rangers were Indian exterminators; the soldiers were only guards.” They also played a special role on the Mexican border, continually reminding those Mexicans living north of the Rio Grande that the tejanos had won the Battle of San Jacinto. On one memorable occasion, a few Rangers invaded Mexico, attacking a heavily armed rancho to regain some rustled King Ranch cattle. Early Rangers like Rip Ford and Ben McCulloch would charge a band of Comanches or confront an angry mob singlehandedly, but as the Indians vanished and the border settled down, the Rangers had to adapt to a new role. Some say they were never the same once they exchanged their horses for automobiles, once they became just another breed of peace officers, constrained by bureaucrats and red tape. They couldn’t be the law anymore; they had to serve it.

Throughout their history, the Rangers have always found it easier to handle Indians than politicians. This was particularly true from the turn of the century until Governor James Allred instigated sweeping reforms in the state police force in 1935. Until 1935 the Rangers were the state police, operating under the direction of the adjutant general. These were times of world war and revolution in Mexico, of Prohibition and oil boom towns, of political corruption and pitched battles between ethnic groups. And there was turmoil within the Ranger service itself. In those days governors would replace key Rangers with favored lackeys and stooges. The fabled Ma Ferguson discharged the entire Ranger service and replaced it with 2300 “special” Rangers, some of them ex-convicts and others getting ready to be. A legislative investigation in 1919 charged Rangers with crimes ranging from murder to being in the pay of German spies. One of Allred’s first tasks was to cancel all “special” Rangers and to establish new criteria for special commissions not to exceed 300, a legal quota that still exists. Special Rangers (there are about 170 of them today) are mostly agents hired by railroads, cattle ranches, and oil companies, though some of them are merely good ol’ rich boys who get pumped up when they pin on a star.

Although Allred’s reforms created the modern agency called the Department of Public Safety and placed the Rangers under its direction, it did not impede the power of a governor to use the Rangers for his own purposes. As an intimidating arm of the governor, Rangers have been called on to break strikes, suppress minority groups, and generally chill political dissent. This practice seemed particularly blatant in the sixties. When John Connally was governor, the Rangers built a reputation for brutalizing Mexican Americans in the Valley. The first incident was in 1963 when Crystal City’s majority emerged and elected all Mexican Americans to the city council. Under the command of Captain A. Y. Allee, Rangers were sent to “keep the peace,” which Allee apparently proceeded to do after his own fashion. He was later charged in a civil suit with cursing at Mayor Juan Cornejo and then banging his honor’s head against the wall six times.

But the bad blood in Crystal City was tame stuff compared to Starr County, where in 1967 the United Farm Workers was attempting to organize labor. Connally sent in the Rangers after protesters burned down a railroad trestle, stopped a train by lying across the tracks, and defied state laws against mass and secondary picketing. Whatever his original intent, the effect of Connally’s order was to break the back of the UFW’s attempt to organize. Various Rangers were accused of smashing demonstrators in the face with shotguns, demolishing union cameras and exposing film, threatening to drown one UFW organizer, and, in at least one case, dangling a union man alongside a railroad track with his nose inches from a fast-moving freight train.

As in Crystal City, the villain of the Starr County war was A. Y. Allee. The captain was a gruff old veteran of Ranger wars dating back to boom town campaigns. He was truly carved out of the best Ranger tradition, which critics thought was precisely his problem. As the old captain told a New York Times reporter, “Those people, by George, started to picket fifteen to twenty at a time. They didn’t work and didn’t want to. They said they wanted to be arrested, and, by George, I accommodated them!” No Ranger in modern times (if ever) has received the heat Allee did over the Dimas incident in Starr County. Magdaleno Dimas was a United Farm Workers organizer with a long police record and heavy Teamsters backing, none of which made him the type of person A. Y. Allee would take to lunch. After several minor skirmishes, the captain chased Dimas home, kicked down the door, and whacked poor Magdaleno across the chops with the barrel of his shotgun. For this Allee was required to stand up before a special three-judge federal court in Brownsville and explain his actions. Allee said he was only doing his job. In an attempt to portray Allee as a racist killer, a union attorney kept accusing the old captain of disliking Dimas.

Allee reminded the court that Dimas had a highly unsavory police record. As to the charge that he tried to kill Dimas, Allee responded: “I could have killed him if I wanted to, but I didn’t want to kill him. Didn’t want to hurt him. I could have shot him three or four times before he got in that door if I was that kind of feller. I didn’t want to.” When the union lawyer pressed on with his belief that the captain had tried to kill Dimas, Allee snorted, “If I wanted to kill him, I’d probably take a little Bee Brand insect powder and kill him. Hell, it won’t take much to kill him.” Allee took the heat for Starr County, but the real villain was the secondary picketing law, which in 1972 was found to be unconstitutional.

As a practical as well as a public relations matter, a Texas governor would have to be faced with a very serious labor riot before calling in the Texas Rangers today. “The tendency now is to use uniformed people at labor locations,” says Colonel Wilson Speir, choosing his words carefully. “Some people felt the Rangers misused their authority in the Valley incident. But remember, Texas had a law against secondary and mass boycotts. Later, the federal courts threw the law out. Therefore, we are no longer required to enforce that law.”

It is the job of the Texas Rangers to investigate major crimes, make arrests, and assist local law enforcement agencies. Though the Rangers are the crème de la crème, they are only one of four services within the DPS Criminal Law Enforcement Division. They are not even the largest. The Legislature currently authorizes 94 Rangers, compared to 124 narcotics agents, 50 criminal intelligence agents, and 22 motor vehicle theft officers. Still, the Ranger badge is the highest honor accorded to a lawman in Texas. Something like 80 percent of the current Rangers came up through the DPS ranks.

Each year the DPS receives about three hundred applications for Ranger service, of which maybe a third qualify to take the entrance exam. An applicant must be between thirty and fifty, have at least sixty hours college credit and eight years experience in law enforcement, and possess a spotless record. Of the hundred or so who qualify to take the written exam, only the top thirty appear before the Oral Interview Board. Of the thirty, maybe three or four will be certified as “eligible.” Last year there were three eligible applicants and two vacancies. “We’re probably the only police force anywhere that doesn’t recruit,” says Captain Bill Wilson, a former University of Texas football player who is supervisor of the Ranger service. “We’re kinda proud of that.” Four of the 94 Rangers have Spanish surnames, but there has never been a black Ranger, much less a female. “As far as I know, we’ve never had a woman applicant,” says Speir.

Rangers are paid the same salary as Highway Patrol sergeants, $1302 a month. They are furnished with a .357 shotgun. They get a $500-a-year clothing allowance. Except for the Stetson and boots, there is no official Ranger uniform. In the sixties Rangers were required to own a gabardine suit for ceremonial purposes, but that requirement was dropped. Most Rangers these days prefer leisure suits. A Ranger’s proudest possession is his badge, traditionally made from a Mexican five-peso piece. The origin of this practice is not clear, but in the old days Mexican silver was soft enough to cut easily with a knife, and taking a five-peso piece from a Mexican was no great chore for a Ranger.

Given all this tradition and mythical status, you have to wonder what Ranger Bob Doherty was doing messing around with a nickle-and-dime marijuana bust. Captain Bill Wilson told me, “He had initiated the case himself, using information he got himself from a man in jail. It was just good, sound police practice is what it was. One fellow led him to the other fellow.”

But was it sound police practice to surround that farmhouse in the middle of the night unannounced and wearing civilian clothes? They could have easily come back the next day, or better yet, grabbed Greg Ott on his way to class. The Texas Rangers made 1764 felony arrests last year, and in no case that anyone could remember had it been necessary to act like they had Machine-gun Kelly trapped in an attic. Captain Wilson reminded me, “Any narcotics dealer who carries a gun has got to be considered a major criminal.” But Greg Ott was no major criminal, not until Bob Doherty was dead. What compounded the tragedy of February 20 was that it never should have happened.

If someone had walked into the philosophy department at NTSU on the morning of February 21 and announced that God had caught his fist in the soft drink machine, it would have made more sense than the news that Greg Ott was in jail charged with the capital murder of a Texas Ranger. One of the women quickly charted Ott’s biorhythms and reported that he was in triple crisis. She could only wonder about the dead Ranger. Everyone knew that Ott dealt a little weed, that was no big deal in a college town, and of course he was a trifle weird, as were most of his friends. “You see a slice of strange people in any philosophy department,” Professor Pete Gunter said. “But I’d have to say Greg was less kinky than most. He was the last person in the world I would have expected to shoot someone.” They were already speaking of Ott in the past tense, as you do when anyone’s life has changed irrevocably. A Texas Ranger. Unbelievable!

In his seven years of college Ott had been a fairly good student, and in the last year or so an exceptional one. He had graduated summa cum laude with a psychology degree the previous December. Now he was heavily involved with Heidegger, existentialism, Zen, and Buddhism. There had been an occasional girl friend (he was married once briefly), but Ott stayed pretty much alone, living in the country with his cat and his books and his leather-working equipment. His place, which he rented from Twin Pines Ranch, was a shanty onto which he had added two rooms, more than doubling the original size. In a workshop near the house, Greg and his partner Ron Mickey made belts, purses, vests, whips, and other leather goods that they peddled around campus.

Greg had had a bad time a few years before. He had been hooked on heroin, but now he was clean and gave every indication of staying that way. His friends seemed to think he had pulled himself together in recent months, and they were happy for him. But the heroin had permanently damaged his liver and he confided to friends that he didn’t expect to live long. “The thought that he might be dying made it hard for him to get close to anyone,” said Shirley Smith, who had dated Ott for about a year.

As a dealer of marijuana, Ott was small onions. He never had much money. If there is such a thing as grooving on poverty, Greg grooved on it. He didn’t talk much and when he did it was about Heidegger and nirvana and what he called “the Oriental no-mind concept of life.” Cathy London, another philosophy student, explained, “It was the idea that you flow with the movement rather than consciously exert yourself.” What made no sense to Mary Collins, an anthropology student, and to most of his other friends, was the gun. Three guns, actually—a pistol, a rifle, and a shotgun, all loaded. “Why did he have the gun?” Mary Collins asked. “Without the gun none of this would have happened.” Dr. Richard Leggett, who had talked on the telephone to Greg just minutes before the cops arrived, was also puzzled. “Everything he believed in was essentially nonviolent,” the professor of philosophy said, shaking his head.

Something had happened a year or so before, something traumatic and senseless. No one seemed certain of the details, but three men with shotguns had forced their way into Ott’s house, tied up Ott and a girl friend, and stolen some goods, including all his leather-working equipment. “He said it was the most fearful moment of his life,” Cathy London recalled. “He had never experienced such a feeling of total hopelessness. That’s when he got the guns.” Maybe the experience changed him, or maybe it just brought him back to a place he had been before. “You know how dope dealers like to play big shot,” another girl friend said. “They talk about blowing away pigs and stuff. They don’t mean any of it. It’s the old macho thing.”

Nobody who knows him likes to talk about it, but ten years ago Greg Ott spent fifteen months in psychiatric detention at Timberlawn in Dallas. He was seventeen at the time. The son of a career Army officer, Greg had stabbed another teenager at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio. This wasn’t the first time he had demonstrated tendencies toward aggression. He had once tried to stab his mother and, on another occasion, his older brother. Faced with the choice of being prosecuted for assault or submitting to psychiatric care, Ott bent to his family’s wishes and entered Timberlawn. The diagnosis was paranoid personality.

In a hearing last March, Dr. Doyle Carson, who had treated Ott, pointed out that a person with a personality disorder shouldn’t be confused with a psychotic. “A personality disorder is more in the area of someone having immature features about his personality.” One trait of a paranoid person is hypersensitivity, which causes him to think frequently that people are mistreating him. Ott’s pattern of response to insults had been, in the doctor’s words, “to defend his self-esteem by striking back physically.” Carson thought that Ott felt his masculinity was being threatened. “He had a lot of doubts about whether or not he was strong and manly and would interpret critical comments directed toward him as meaning he was weak.” Carson also explained that personality disorders are not unusual in late adolescence, but it is not unusual for a person to outgrow the problems.

Greg Ott was not discharged from Timberlawn. After fifteen months there he just ran away. Dr. Carson recalled that he refused a staff recommendation to have Ott readmitted. “He simply wasn’t heading in the same direction we were,” the doctor said. By this time Ott’s parents had moved out of the state and he was on his own. You might say he became a man at Timberlawn. About that time Ott met Ron Mickey, who for the next ten years would be his closest friend. “They were like brothers,” Shirley Smith told me.

Nothing had ever shaken the scholarly community of Denton like the slaying of the Texas Ranger. There was hatred and sorrow and great confusion as people tried to sort out the details. The case was less a murder than a political hot potato. If the victim had been someone else, one of the deputies, for example, the case would have attracted very little attention, and District Attorney Jerry Cobb might have been inclined to file a lesser charge than capital murder. Cobb had never had a capital murder case; to memory, there had never been a capital murder case tried to conclusion in Denton. Cobb was only 34 years old; it was a type of political pressure he could do without.

“Hell, yes, I’m on the spot,” Cobb admitted weeks before the trial. “It’s not a capital offense unless you can show that the officers were acting in the lawful discharge of their duty and Ott knew they were police officers. You always have trouble proving it when the officers are not in uniform.” There were times when Cobb must have thought the case hopelessly circumstantial. No one actually saw Ott pull the trigger. The bullet that killed Bob Doherty had been so badly fragmented it was impossible to say it came from Ott’s .38. Witnesses told conflicting stories. Captain Dwight Crawford claimed that he shouted “Police officers!” twice before a shot was fired, but agent Ben Neel, who was inside the house with Ott and Jimmy Baker, didn’t hear him. Deputies Gilliland and Douglas had sworn that as they were climbing out of the truck they heard voices inside shouting “Drop that gun or I’ll kill you” and “He’s got a gun,” but agent Don Jones, who was much closer to the house than the deputies, didn’t hear either shout. Neel claimed that he shouted “Police officer! Freeze!” just before he fired at Ott. Could this have been what Gilliland heard? Not likely, because by the time Neel shouted this, Deputy Gilliland had already made his way to the northwest corner of the house where Doherty was about to kick in the door. Remember, Neel had just spent considerable time and effort convincing Ott he wasn’t a cop. The whole fiasco took place in a matter of seconds. Wasn’t it reasonable to believe that Greg Ott didn’t recognize this as a police raid until after the Ranger was killed? Some of the officers agreed that the first thing Ott said after he surrendered was “Why didn’t you tell me you were police officers!” So this was Jerry Cobb’s case and he had no choice but to pursue it with a vengeance.

There was a lot of backstage maneuvering in the days just after the killing. Jimmy Baker, who helped set up the raid, had also been charged with capital murder, but that charge was quietly dropped, and after some days of freedom Baker went to federal prison for violating probation. Kenneth Ray Bunyard, who had started the whole chain of events, now volunteered the information that while trying to take a nap in his cell he overheard a conversation between Ott and one of Ott’s attorneys. According to Bunyard, Ott admitted he saw someone at the door just before he fired. A day after the killing, Bunyard and Mary Nosser were married in jail. By the time the trial started in May, Bunyard was again walking the streets of Denton. Jimmy Baker, the only eyewitness who was not a cop, first confirmed the police version of what happened at Ott’s house, but two months later, in a taped interview with his lawyer, Baker changed his story, claiming the only reason he lied in the first place was that two Rangers threatened to kill him in his cell. Baker now claimed that Ben Neel fired not one but two shots, and that Ott fired back at Neel rather than at the door, which would have been in the opposite direction. If Baker was telling the truth, the bullet that killed Bob Doherty must have come from Neel’s .45. Certainly there was plenty of time that night for a cover-up, and without an identifiable bullet, who could say?

It would be up to Jerry Cobb to convince the jury that Greg Ott wantonly and deliberately killed a Texas Ranger, his motives being to save himself and protect his stash of marijuana. The jury would have to believe that Greg Ott was a violent and dangerous man who had killed once and if set free would likely do so again. It would be a tall order, but by the time the trial had ended Cobb had not only convinced the jury, he had also convinced himself. What is more, he had convinced Alan Levy, one of the two lawyers hired to defend Greg Ott.

Retired Colonel Bruce Ott had spent more than twenty years in the military and been around the world a time or two, but until he watched his son tried for capital murder he had never been inside a courtroom. He was a stiff, curt, red-faced man with silver hair and bifocals, good Pennsylvania Dutch stock. He was a self-made man. Against his family’s wishes he had worked his way through veterinary school and now held a top position as head of research for a New Jersey pharmaceutical company. Marion Ott came from a well-placed family on Long Island and could still laugh about the time long ago when Bruce’s family thought filet mignon was the name of her French poodle. Greg was the second of their six children. Their oldest son lived in New York and was an airline pilot. Mary Ott Joyce, their only daughter and the apple of her daddy’s eye, was married and lived in Michigan. The next brother was studying medicine in California, and the two youngest boys still lived at home in New Jersey. “It’s brought us all together,” Bruce Ott kept telling people. But it went without saying that this was the worst experience of their lives.

It came as no shock to Marion Ott to learn that her son was fooling around with marijuana, but the old colonel was dumbfounded. The connection of his son with two crimes, marijuana and murder, was almost incomprehensible. Bruce Ott sat in the courtroom next to his wife and daughter, trying very hard to sort it out. Marion Ott knew as a certainty that her son did not deliberately kill a Texas Ranger, and the colonel had sworn to spend his last dime if that’s what it took to get an acquittal in the murder case. “I guess I’m the redneck’s redneck,” he said at one point, “but why did he have to be messing around with marijuana?” His daughter, Mary, reminded him that he was exceptionally fond of martinis. He reminded her that martinis were not illegal. The second or third day of the trial Mary amazed herself by blurting out, “Daddy, would it shock you to know that I’ve been smoking marijuana for five years?” Only a lifetime of military bearing prevented him from crying. All he could say was “I’m very disappointed in you.”

The Otts had retained the two lawyers originally appointed by the court. Hal Jackson and Al Levy were respected courtroom lawyers with good local connections. They were known as the Odd Couple. Jackson was the 58-year-old silver fox of Denton criminal law, a lifelong native and a highly decorated war hero; Levy was a 28-year-old boy wonder in town who had immediately tested the waters by running for district attorney. Levy had run against Jerry Cobb and Cobb’s top assistant, Fred Marsh. The three of them remained good friends. Marsh and Cobb frequently kidded Levy that his one mistake was running as a Republican. Jackson was the odd part of the couple. He regarded prosecutors as worthy quarry, but damned if he would go for the throat and damned if he would let the other fellow go for his. Whatever their differences in age and style, Jackson and Levy worked well together. Levy was glib and funny and self-effacing, while Jackson played counterpoint as the stumbling old fool, leading juries up alleys of his choice and then pouncing on them.

Once the town had recovered from its initial hysteria, Levy and Jackson put their plan into action. The first order of business was to prevent future outbreaks of hysteria—the emergence of another unexpected jailhouse informant, for example, or loose talk about their client’s days at Timberlawn. Several of Greg’s old friends were urged to take long vacations, including Ron Mickey, who according to a report was threatening to bring a Dallas motorcycle gang to town and lead a jailbreak. Their defense rested on the well-founded theory that an intelligent, independent-minded jury would see the incident of February 20 as a massive police foul-up.

There was reasonable doubt that Greg Ott even fired a pistol, much less at a man he knew to be a cop. There was hardly any physical evidence, and part of what the prosecution had was mutilated by the bunglings of the Denton sheriff’s office. The state might have proved the bullet hole in the door was made with a .38, except some deputy had rammed his pencil through the hole so it would look neater. The test that could have proved that Greg Ott indeed fired a pistol that night was inconclusive because the deputies had first insisted on fingerprinting their man. Jackson had calculated that the state’s weakest witness would be agent Neel, who fired the first shot. Neel’s own record was not lily white. He had been involved in other dope shootouts and had killed a suspect in an abortive dope raid in Houston. The most recent example of Neel’s proclivity toward the wrong move came less than a month before the killing of Ranger Doherty. Neel awoke one morning to find not only his prize informant but also $9500 in state buy money missing from his home. The informant’s whereabouts and how he managed to get the money out of the locked trunk of Neel’s car were mysteries that still bothered the DPS. The department had suspended Neel for five days, which indicated they were not entirely happy with his performance.

Unfortunately for the defense, Jackson was not able to get much of Neel’s biography to the jury, but he still had a use for him. During direct examination, the prosecution had asked Neel to step over to the schematic near the jury box and draw the trajectory of the shot he fired at the fleeing Greg Ott. When it was the defense’s turn to cross-examine, Jackson asked Neel to return to the schematic and continue his line of trajectory. Cobb quickly objected, and Judge Bob Scofield, who several times seemed on the verge of having Jackson clamped in irons, just as quickly sustained the objection. But it didn’t matter. Suddenly everyone in the courtroom was drawing a mental trajectory. The bullet would have gone right through the door where Ranger Doherty was killed.

When it came time for the defense to present its case, Levy and Jackson had to answer one quick and momentous question: had the state proved its case? Although the jury had been permitted to examine a photograph of Ott taken on the night of February 20—the one in which he looked like Charles Manson—the defendant they had seen in the courtroom was scrubbed, groomed, and attractively attired in a three-piece suit borrowed from Jackson’s closet. This was the impression they hoped the jury would take with them. Levy took a straw vote among members of the press, who mostly agreed that the worst they could get was involuntary manslaughter and long probation. The lawyers weighed whether to call Jimmy Baker as a witness and decided it was a poor risk. They would have to vouch for Baker’s reputation, which was hardly what their client needed at the moment, and they couldn’t really be sure what Baker would say under oath. “Anybody who tells two different stories has obviously lied once,” Hal Jackson reasoned. The only other nonpolice witness was Ott himself, and they would call him only as a last resort—in the punishment phase after a verdict of capital murder. They couldn’t afford to open up Ott’s psychiatric record, however dated and oblique. The jury already knew that Ott was a dope dealer; if they also had to wrestle with expert testimony that he had once been diagnosed as having paranoid personality with aggressive tendencies, then, sir, it would be time to make a fist and wait for the last needle.

Levy and Jackson decided to call only three witnesses, all of them law officers who would testify that the mysterious Jimmy Baker had also been charged with capital murder. This was done merely to make the jury wonder, Where the hell is Baker and why didn’t the state call him as a witness? Only an hour or so after the defense began, it rested its case. Things looked pretty good. Bruce Ott was so happy that he offered to buy martinis all around. Marion Ott protested that it would be bad luck to celebrate prematurely and led the colonel off by the arm. In retrospect, it was a wise move.

Al Levy’s closing statement was predictably incisive, except for one very unfortunate slip. Pointing to the door with the hole, which sat in the middle of the courtroom, Levy told the jury, “When Greg Ott fired that shot . . .” Say what? This was the first and only evidence the jury had that Ott did fire a shot. When someone asked Jerry Cobb later why he didn’t pounce on Levy’s slip in his own closing statement, the young district attorney said sheepishly, “I was thinking so hard what I was going to say I didn’t even hear him.” Cobb’s final statement was short and explosive. He described Greg Ott as a “man ready to kill for his stash,” and demanded that Ott be convicted of capital murder and pay for his crime with his life. Later, outside the courtroom, Cobb would fight back his own tears and describe it as the hardest thing he had ever done.

It took the jury about four hours to find Ott guilty of the lesser crime of murder.

When Judge Scofield read the verdict, the only one at the defense table who didn’t look slightly relieved was Greg Ott. There were tears in his eyes as he was led off in handcuffs. The jury would still have to come back in the morning and deliberate the sentence, which could range anywhere from five years to life. But the threat of the death penalty had ended. “It feels like a tie,” Al Levy told reporters. Levy seemed as relieved in defeat as Jerry Cobb did in victory, and Bruce Ott watched in wonderment as the two lawyers shook hands.

“I can’t understand lawyers,” the colonel said, shaking his head. “They laugh and joke with each other while my son’s life is at stake.”

That night as Levy, Cobb, and Fred Marsh were cooling their emotions and indulging in some serious drinking, Levy called it “probably the best verdict I’ve ever seen.”

“Ott’s a violent and dangerous person,” Jerry Cobb said. “His whole personality proves it.”

“If he hadn’t killed the Ranger he would have probably ended up killing someone else,” Levy agreed.

“Where’s your evidence?” I asked the lawyers. I hadn’t seen it. The psychiatric report was ten years old and vague to the point of being irrelevant. True, Ott didn’t conform to some people’s standards of behavior, but not a single witness had testified to an act of aggressive behavior since that time long ago in San Antonio. “I got some pictures to prove he was into S&M and bondage and all kinds of kinky sex,” Cobb said. “Come to my office in the morning and I’ll show you.” The following morning, with a couple of Texas Rangers looking over my shoulder, I examined the material seized from Ott’s home. There were photographs of whips, body harnesses, dildos, and spiked collars, the sort of stuff you’d see in any pornography shop. There were also some lesbian magazines and a book titled Sex with Dogs. “What do you think the jury would have thought if they’d seen this stuff?” one of Cobb’s investigators asked.

The only witness called by the defense in the punishment stage of the trial was Greg’s mother. She was not called as a character witness—that would have opened up those doors Levy and Jackson wanted shut—but rather to testify that her son had never been convicted of a felony. But, on the grounds that she hadn’t really kept up with her son for ten years, Judge Scofield refused to allow her testimony. Greg Ott kissed his mother’s hand as she walked down from the witness stand. She didn’t have it in her to smile again. A few hours later, when the jury returned and sentenced Greg Ott to life in prison, Marion Ott fainted.

I do not know what went through the minds of the jurors, but I think they felt obliged to pinpoint the blame for the tragedy of February 20. Obviously the jurors believed that Ott did not know he was shooting at a cop, otherwise they would have found him guilty of capital murder. But if Ott didn’t know the man on the other side of the door was a cop, who did he think it was? The prosecution argued that he shot to protect his marijuana, but I don’t think this is a reasonable assumption. In the few seconds of action, all Ott really had time to know was that his house was being broken into from all directions and that he was being shot at. In that situation my guess is that he did what any other Texan inside his home with a gun in his hand would do. He fired back. Because of fate, a member of one of the legendary police agencies of the world was killed. I believe that in their honest attempt to attach blame, the jurors reduced the tragedy to a single notion: dope dealer kills Texas Ranger. No matter how they weighed the evidence, that was the crime.

What lingers is not so much the crime as the tragedy. Caught up in the scent of the chase, five heavily armed law enforcement officers, none in uniform, surrounded an isolated house in the middle of the night, hoping to trap and arrest a man with twenty pounds of marijuana. That is their duty, but why were they pursuing it as though they had just cornered the whole French Connection? Ott was a dealer of illegal chicken feed, not an all-points-bulletin fugitive. He wasn’t going anywhere, except to class the next day. The crime of selling twenty pounds of marijuana to an undercover agent would probably have been worth no more than a long probation in Denton County. It wasn’t the crime that obsessed the officers; it was the chase, the irresistible urge, against common sense, to play cops and robbers. Because of this, a Texas Ranger was killed and a 27-year-old graduate student will spend at least the next twenty years of his life in prison. Bob Doherty should be taking his long-overdue vacation right now, just as Greg Ott should be working on his master’s thesis and living according to the terms of his probation. Instead, two lives are destroyed. This is the tragedy for which no blame has yet been fixed.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Fort Worth

- Denton