This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The best boxers often have the smoothest faces. To anyone who watches fights even casually, a gifted boxer’s ring strategy seems the wisest, the safest, perhaps even the most historically correct way to go about such a business—hit, then, try not to get hit back.

Many of the best boxers are also stark-raving conspiracy theorists. They are convinced that subterranean forces attached to prizefighting are plotting against their careers. They can believe in any number of the game’s unwritten axioms—for instance, people in boxing will stab you in the back just to see how well you bleed.

“Ahh,” Donald Curry says when he is told about that axiom, his eyes lit with something like poetic recognition. “I’ll have to remember that one. Yes, that one I will remember.”

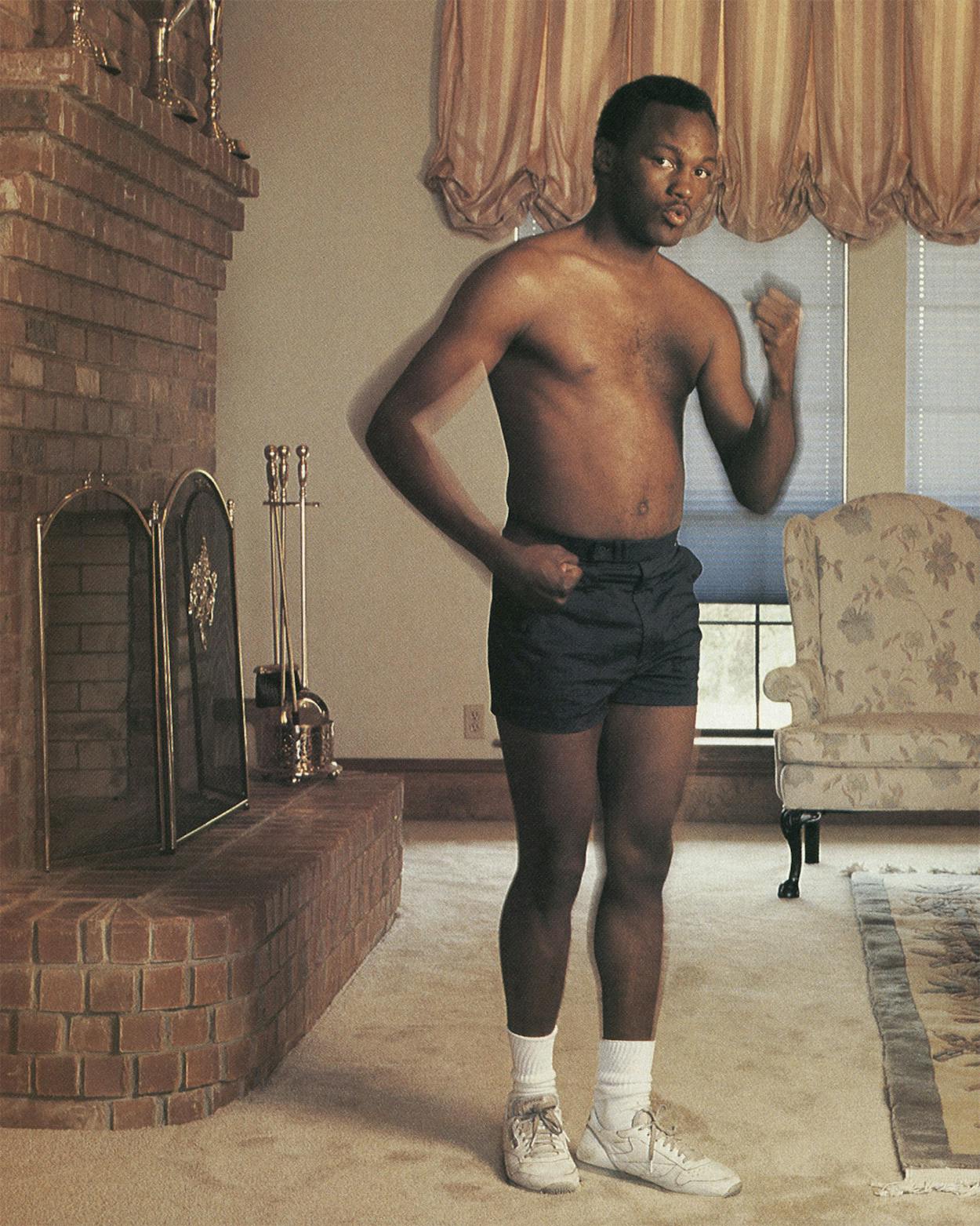

Donald Curry’s face is smooth and handsome and even a little iridescent when it catches the light just right. He is a classically beautiful man with the physique boxers pick up from what now seems like the quaintest forms of exercise: doing push-ups and sit-ups, running empty roads early in the morning, and skipping rope. Without ever having lifted weights, Curry has a rippled torso, muscular shoulders, a broad back, and a steep, flexible neck, all packed into a five-ten frame. As a fighter, he has sent 20 of his 28 opponents to what the boxing wags call Queer Street, an address in the state of unconsciousness. In reward, Curry has earned nearly $4 million over the past seven years. In 1985 he earned $1.5 million in purses, a feat that made him the highest-paid athlete in Texas that year.

But it has been a while since the 25-year-old Fort Worth native has made that kind of money. Curry’s last two fights earned him a total of $200,000—not chicken feed, to be sure, but not the king’s ransoms he seemed destined for a year ago. Back then Curry was the world’s welterweight champ (up to 147 pounds), and his name was brought up in newspaper columns in the company of such current and all-time boxing lights as Marvin Hagler and Sugar Ray Robinson. Whether that status is possible again for Curry could be decided on July 18, when he fights for a new title. Last fall he lost his first title. The upcoming fight, for the world’s junior middleweight championship (up to 154 pounds), will determine Curry’s future—whether his career is all in front of him, as he believes it is, or whether it is largely behind him.

A year ago Curry’s future was in his hands, as it had been since 1983, when at age 22, after only fifteen pro fights, he won the welterweight title of one of boxing’s three sanctioning bodies that regulate championships. Within the next three years he went on to win the two remaining titles, the first boxer to do so in the welterweight division since Sugar Ray Leonard’s retirement in 1982. Suddenly Curry’s name was mentioned whenever the sport’s cognoscenti began discussing their candidates for the best pound-for-pound fighters, a distinction that judges a boxer on his strength and expertise, regardless of his size.

Curry is known in the trade as a boxer puncher—a fighter lettered in technique yet capable of knocking his opponent flat with either hand. One observer says that Curry “represents the sweet science”—a boxer of a skill and knowledge so rare that the game’s most critical believe he has the potential to make boxing history. The guys with the bent noses and thick locutions say Curry is the classiest thing boxing has to offer. The word they most often use to describe him is “gentleman,” with equal accent placed on “gentle” and “man.” Even outside the ring, he is quiet and humble.

Then last September Curry lost his first fight, to an untested underdog from Britain, and the conspiracy theories flew thick and fast from every direction. In the end, Curry had accused everyone in sight. He accused his manager of picking his pocket and his promoter of trying to purchase his soul. Curry blamed himself but also accused another boxer, Ray Leonard, at that time his personal and corporate model, of stabbing him in the back. Curry went from a $750,000 purse in 1985 and a guaranteed $1 million for a fight in 1986 to the $100,000 he made for a fight last April. For the first time, Curry saw just how fragile a career in the ruthless and money-driven sport of boxing can be. Bob Arum, who has promoted all of Curry’s fights, sets the cost of the loss to Curry’s career as high as $10 million.

Now Curry is trying to fight his way back, a little tarnished and reduced in the eyes of those who once lauded him, but still confident in the knowledge that all great boxers have lost and that it’s how they came back that really mattered.

The boxing world, meanwhile, is simply standing aside, trying to see how well Curry bleeds.

Everything is waiting for that bell,” Curry is explaining as he relaxes in a country French chair in his twenty-fourth-floor suite at the Union Plaza Hotel in Las Vegas, boxing’s promised land.

Curry has missed two interviews in the last two days, and he is apologetic, but not overly so, when we do meet. After all, he is here now. As talented and gentlemanly as Curry is outside the ring, it’s not long before one gets a sense of his fabled lousy timing—so far, his legacy. Even in Las Vegas in April, where the stage was set for him to shine before the boxing world assembled for the Hagler-Leonard fight scheduled two days after his own, Curry won his fight on a fifth-round disqualification after his opponent butted him in the head. The match left those who had been anxious to see Curry in action feeling once again a little delayed and incomplete.

“To train so long and then release all that nervous energy is beautiful,” Curry continues, talking about the thoughts he has as he enters the ring. There’s something felonious about Curry when he steps through the ropes. His deep dark skin seems to turn even darker, his anger, concentration, and willingness to seriously debilitate another man all focused in a grim, undetonated expression. Curry has compared the metamorphosis to becoming a beast. “I look across the ring with a kind of tunnel vision,” he says. “I don’t see anything else. I can’t hear anything. It’s like I’m in a box. I put myself in the other guy’s place. I try to think what he thinks my weaknesses are, what he thinks he could possibly do to me that these other guys couldn’t do. Then I just want that bell to hurry up and ring.”

Curry’s slim hands are settled in his lap. He pauses to take a sip of hot tea. “I’m getting angry,” he goes on. “I become somebody else. I become the person I’m not outside the ring. I’m ready to express all the things I never say. I’m vicious.” Curry pauses for another sip. “I want to hurt the other guy—as a sport. I just keep saying to myself, ‘C’mon, bell. C’mon, bell.’ ”

As a group, boxers are probably less like their performing images than most athletes are, and Curry is less so than even most boxers. “If you did not know Donald Curry, you wouldn’t know he was a fighter,” says Arlen “Spider” Bynum, a Dallas attorney and boxing official who has known Curry since his amateur days. “I think of a fighter as being onstage all the time, or as someone with an overwhelming presence or with a big entourage around all the time. Donald’s different. He seems too nice to be a fighter.”

There is a bit of the internal spelunker about Curry, a tendency to go deep with a thought or mood or situation. The first time Curry and I met, in an office inside Gorman’s Super Pro’s Gym on Fort Worth’s South Side, I started the conversation by asking him how he felt. That’s a standard entry with most boxers, because their physical well-being is often the foremost thing on their minds. Their replies are usually as standard as the question. But when I asked Curry, he paused for a long, contemplative moment. Then he sighed, raised his palms, smacked his lips, and answered, “Oh, you know, it’s just been one of those days. I’ve been real moody all day. I don’t know. I’ve had some problems today. My moods. I’ve just been like this all afternoon. I don’t know what it is.”

In sports, that kind of self-examination seems out of place. The aficionados gathered in Las Vegas during Curry’s last fight were puzzled by his stalled career, and they often attributed the problem to some invisible, internal process. “Magnificent boxer,” said Bert Sugar, the former editor of Ring magazine. “But . . . but a real head case, isn’t he?” Bob Surkein, the head of the Olympic boxing committee when Curry was an amateur, put it another way: “He’s a credit to sports and deserves nothing but the best. But there’s a real inner battle he’s fighting.”

Curry is protective of his privacy, and whatever his conflict may be, it isn’t anything obvious. A lot of boxers seem to be in the ring to exorcise some jumpy, poverty-induced demon that ritualized violence allows them to confront. One boxer at Gorman’s gym told me how he began to box in the Army to keep from slugging an officer; another talked about how exciting boxing seems compared with the life he had lived in a Mobile, Alabama, ghetto. But Curry’s fury appears to be more the operating method of a highly skilled mercenary who does what he does because he can do it so well.

“I’m good,” Curry says, without inflection. “I mean, I’m good.”

Curry did grow up poor, but not angry. He was one of five children raised in a house on Shaw Street on Fort Worth’s South Side. His natural father left before Curry knew him, and Curry grew up with a stepfather who he never realized had taken his father’s place. “It was your typical black family,” Curry offers. “We grew up poor and underprivileged. I was just never aware of it.” His neighborhood was loaded with kids who boxed, and Curry had his first of more than four hundred amateur bouts when he was eight. He won. “I was real competitive, even then,” he says. “I always wanted to be something special, to stand out in a crowd. But I always let my talent speak for itself.” He was private and soft-spoken, a “tough, nice kid,” he says, who never had a fight outside the ring. His mother, who worked as a hospital maid, called him “my quiet one.”

Curry moved to a nearby South Side neighborhood shortly after his first fight. Nobody there boxed, but they did everything else: football, basketball, track. Curry appeared even then to have an intuitive grasp of whatever game he played. “He seemed ahead of things,” recalls Alfred “Doug” Jackson, a boyhood friend who now works for Curry as a glorified Guy Friday. Curry quarterbacked a peewee football team Jackson played on that seldom lost. “It was like the coach would send in a play, and Don would say, ‘That won’t work; let’s run this,’ and the coach would say no, and Don would run his own play anyway,” Jackson says. “And then he’d score a touchdown.”

Curry continued to box too. When he worked out, which wasn’t often, he went to a gym where Paul Reyes, then a General Motors assembly-line worker in Arlington and today Curry’s trainer, ran an amateur boxing program. Reyes says Curry was a natural, so he spent less time with Curry than with most of the fifty other kids he trained. “I never had to worry about Don,” Reyes says. “He always won.” Curry says, “I enjoyed the notoriety. I didn’t care about all of Fort Worth knowing about me. I just wanted to be well known in my neighborhood.”

But Curry quickly became known in amateur boxing circles across the country. By sixteen, the earliest age possible to box in the open division, he had won a national Golden Gloves championship. But even as his reputation rose, Curry was diving deep. “I’d question why I’d win so much,” he says. “ ‘I’m sixteen, and I’m national champion. Why me? Why am I so good? Why am I as good as people say I am?’ ”

By that time, Curry had fought in well over three hundred amateur matches and felt himself burning out. So he took the next year off, except for the major tournaments. In 1980, as an eighteen-year-old senior at Paschal High School in Fort Worth, Curry returned to boxing rejuvenated.

Then his career received the first blow. It was an Olympic year, with international boxing still riding the wave created by the U.S. Olympic boxing team four years earlier. Many of the boxers in the 1976 Olympics received purses in their first pro bouts many times what purses had been previously. Ray Leonard, for instance, received $40,000 for his first fight, which was also shown on network TV. In contrast, Marvin Hagler, who turned pro in 1973, had fought his first bout for $50. Curry—stylish, cool, good-looking—was already seen as the next Leonard, both as a boxer and as a cash cow. When Curry won the Olympic trials, promoters like Arum began to hum.

Then the U.S. boycotted the Summer Olympics, held that year in Moscow.

Curry wasn’t keen on turning pro anyway. He says his reason was simple: He had seen the worst that boxing had to offer played out on his own older brother, who had turned pro several years before.

Bruce Curry was a talent too, though what he lacked in the kind of natural ability that Donald had in abundance he made up for by being a maniacal gym rat. Bruce worked out constantly, he fought with his heart as much as his head, and he let everyone know he was willing to fight anybody, anytime.

But a boxer is a delicate organism, and maturing a boxer in the ring is one of the subtlest maneuvers in sports. On one hand, a boxer needs to develop what Home Box Office broadcaster Larry Merchant calls “a sense of immortality, that thing that allows a fighter to be better than even he really is.” So for early fights opponents are found whom the boxer is an overwhelming favorite to beat. But a boxer also needs to develop skills won only from opponents who present a particular challenge: technicians, bangers, southpaws, declining vets with befuddling ring savvy. If he gets through those, a boxer then is ready to face established pros, and if he’s not winnowed out by those, then a title shot is the next step.

The opposite of this strategy is practiced by some managers to wring as much out of a fighter as quickly as they can, with little regard for the long-term consequences. Donald Curry believes his brother, Bruce, was mismanaged in this way. “It was tragic,” he says. “Bruce was around people who looked at him as a dollar bill.” Bruce, now 31, turned pro and moved to California with promises of quick titles and fast money. He did make money, but it wasn’t long before he began to meet a series of far-more-polished opponents. After thirteen fights and thirteen wins, he fought Wilfred Benitez, one of the most skilled boxers in the world, and lost a split decision. He was given a rematch, but this time he fought Benitez only ten days after he had had another fight in Japan. He lost again and was moved up in weight to go up against stronger fighters who commanded bigger purses. Bruce did win a junior welterweight title (up to 140 pounds) in 1983, but at the time, the competition was soft and his own skills were in decline. He defended his title twice, but four days after he lost in his third defense, he fired a .357 Magnum at his trainer. A jury found Bruce innocent of attempted murder by reason of insanity, and he spent the next year in a Nevada psychiatric hospital. He is now in Fort Worth, talking about a comeback.

At eighteen, Donald Curry thought he might like to try college instead. He was an average student, but he felt competitive in the classroom too. “A C for me was like an A,” he says. “But if I got a D, it was like the end of the world.” He looked into attending Texas Southern University or the University of Houston. The idea of campus life appealed to him; his brother’s experience certainly didn’t look like the end of any rainbow.

But the boxing world loves nothing so much as a hot property, and there is no governing body like the NCAA to set guidelines on an amateur’s recruitment. So boxing does whatever it has to do to get what it wants, and in 1980 it wanted a nineteen-year-old stylist with a floppy afro named Donald Curry.

Offers came from everywhere: both coasts, Europe, South America. The talk was fast, slick, and often a little oily. There was also an offer from a man in Fort Worth named David Gorman. Gorman was then the owner of a successful masonry business and the manager of one of the best amateur boxing programs in the country. He had watched Curry box since Curry was nine or ten and remembers that he stood out then. Gorman was a self-made bricklayer who dropped out of school in the ninth grade. A former amateur boxer, he had grown up scrapping his way through a predominantly Hispanic neighborhood on Fort Worth’s South Side. Gorman hooked up with Reyes in the middle of Curry’s amateur career, nurturing a stable of fighters that eventually produced three professional world champions and put Fort Worth solidly on boxing’s map.

But back in 1980 the key to that future was Curry, and Gorman knew it. He remembers watching Curry at a Golden Gloves tournament and telling his wife that Curry had the skills of Ray Leonard. After the Olympic trials, Gorman again turned to his wife and said, “If Don’s going to turn pro, why not with me?”

There were a lot of reasons for Curry to refuse Gorman. Gorman had never managed a professional boxer in his life, and though his business was booming, he didn’t have the resources that many of Curry’s other suitors had. But Gorman held the trump card: He knew Curry didn’t want to leave Fort Worth with a stranger and have his career wind up like his brother’s. In 1980 Gorman offered Curry a $20,000 signing bonus, a one-year-old Lincoln Continental, and a supplemental salary to keep him flush. “David didn’t just see dollar signs,” Curry says. “There was something beyond a working relationship. He was a friend.”

Gorman’s first move was to sign with Arum, who immediately made Curry a cable TV boxer. Promoters are the real movers in boxing, particularly Arum and Don King, each obligating as many marquee fighters as possible to control TV dates, matches, and purses. “The power is not with the managers; it’s with the promoters,” Arum says flatly. “It’s like in Hollywood, where the power is with the studios, not the agents.”

So young fighters with marquee potential are courted early. Arum saw uncommon potential in Curry and was willing to stake early losses for the multimillion-dollar payoffs he envisioned down the road. He says his own profit-and-loss statement for Curry’s career is somewhere around $50,000, up or down, and he is not particularly interested in finding out which. “We hope we can get a fighter into those big promotions. Then he makes huge money, and we make good money,” said Arum, who promoted the Hagler-Leonard fight, which at $75 million is the largest-grossing fight in boxing history. While Curry’s early purses weren’t anything like Leonard’s (Curry’s first purse was $3,000), they weren’t bad either, and Arum’s arrangement with the cable networks gave Curry wide exposure.

Curry’s career began with bouts against the usual string of what the touts call tomato cans. But his competition was stepped up early, because Curry was exceptional, Arum anxious, and the competition in the division soft. In 1983, after fifteen pro fights, Curry won the welterweight title of the World Boxing Association. Curry’s purses moved into the middle six figures after that, peaking in 1985 with a $750,000 purse for the World Boxing Council title when he knocked out Milton McCrory.

At that point talk moved to a match against Hagler within the year. That fight would mean the big, big payday for Curry, for Gorman, for Arum, and for whoever else could get in for a piece of it.

Then things turned bizarre. In the spring of 1986 Curry’s camp fell apart like a family in a messy domestic breakup. By that time, Curry was rich, if not yet famous outside the circle of boxing buffs. He was a hero in Fort Worth, where he often found himself standing beside politicians and restaurateurs as flashbulbs went off in his eyes. He bought a gold Mercedes, a black BMW, and a $300,000 house for his mother—not excessive booty for a new millionaire who could expect even bigger riches to follow.

Gorman and Arum were already working on those. Their blueprint after the McCrory fight called for Curry to defend his welterweight title once, then move up to 154 pounds and go for a second title, in the junior middleweight division. That was where Arum planned to turn Curry into a marquee fighter. Arum had made arrangements with a pay-TV outlet to broadcast a three-fight extravaganza from Las Vegas, in which Curry would be the card’s showcase, fighting for a title against Mike McCallum, the junior middleweight champ and a five-to-one underdog. Curry’s $1 million payoff would be the largest of his career, and a win would put his name on marquees in big block letters.

The plan seemed brilliant for several reasons. For one thing, Curry had long had trouble making the 147-pound weight limit for a welterweight, calling his meltdown before each fight “pure torture.” He was also the obvious class of the welterweight division, so no more big paydays loomed there. If Curry moved up, he could win a second title from McCallum, let his body mature casually, then move up six more pounds to middleweight, where there stood the biggest payday of all—Marvin Hagler.

With that settled and with $1.5 million already in the bank from 1985, maybe twice that much possible in 1986, and his career pointed in a direction most boxers spend a lifetime waiting for, Curry freaked.

Curry had become a head case by that spring. His tendency toward self-examination had become an enemy instead of an ally. He wasn’t talking to anybody, including Gorman. Curry now felt that Gorman’s 28 percent cut was too big a bite into money that he took the punches to earn. He also thought Gorman had spread himself too thin, building a stable of boxers with time that Curry felt would be better devoted to him. He was Gorman’s meal ticket; Gorman estimates Curry has made him $1.5 million, from his cuts from Curry’s purses as well as from those of the boxers he has developed since at his gym. “His program depended on me,” Curry says. “I was like the number one draft choice, and he was going to mold a team around this one player.”

Also in the picture by the spring of 1986 was an Arum employee named Akbar Muhammad. Curry and Muhammad had become friends in 1980 at Curry’s first professional fight, in which Muhammad served as the coordinator of ESPN’s boxing program for arum’s Top Rank. The two had hit it off, and with Top Rank promoting all of Curry’s fights, their relationship grew. In March 1986 it was announced that Muhammad had left Top Rank to become Curry’s manager. The announcement was, at best, premature, for Gorman, who had a contract with Curry through October 1986, knew nothing about it. The move was dubbed the “Akbar Wars” at Top Rank, and soon wars broke out all over. Everybody was after a piece of Curry, then seen as the hottest property in the business. But rather than being flattered or seizing the opportunity, Curry felt reduced to dollar signs, as if he were under attack by the same forces he had seen destroy his brother. He was 25, rich, and in way over his head. Finally he left for Bethesda, Maryland, to talk with the then retired Leonard and Leonard’s attorney, Mike Trainer, about their taking control of his career.

Curry had always admired Ray Leonard, in and out of the ring. He especially envied Leonard’s relative status as a free agent. In Leonard’s arrangement, he and Trainer often found the dates, sites, and opponents for Leonard’s matches, thus reducing the promoters’ power and profits. Leonard and Trainer also cut their own closed-circuit deals, negotiating directly with operators they trusted and with whom they believed they could make more money. Promoters hate them.

A short time after meeting with Curry in Bethesda in the spring of 1986, Trainer flew to Fort Worth twice to meet with Curry and Gorman, who by then were not speaking at all. Trainer says Curry thought his career was being manipulated by Arum, slowed by Gorman, and possibly exploited by Muhammad. Trainer says he was trying only to determine what Curry’s obligations were with Gorman and Arum. In the meantime, he says, he told Curry the McCallum fight would still be around in another year, with the possibility of making even more money from it by eliminating Arum and arranging it along Leonard’s freelance model. The buildup to a Hagler fight, so prominent in the plans of Arum and Gorman, suddenly seemed in this new plan not to matter much at all.

In April 1986, less than two months before Arum’s proposed extravaganza, Curry announced that he would remain a welterweight and not fight McCallum. A few days later, Leonard announced that he was coming out of retirement—to fight Hagler. Curry felt duped, believing that he had been steered away from Hagler to grease the runway for Leonard. He dissolved his relationship with Trainer instantly. Curry’s camp contends that had Curry beaten McCallum, he would have been in a position either to fight Hagler first or to force Leonard to fight Curry before arranging his match with Hagler, who seemed content to stand by idly while the world duked it out for the chance to box him. Curry’s camp has since pressed the contention beyond the usual paranoid claims of a young boxer who is feeling it all slip away: On the morning of the Hagler-Leonard fight in Las Vegas, Curry, Gorman, and Reyes filed a $1 million suit against Leonard and Trainer, claiming that they had deceived Curry to accommodate their own interests.

Curry says, “They didn’t stab me in the back—they stabbed me in the chest.” His eyes widen. “I almost lost my life.”

Well, not exactly. But he did lose his next fight, in September 1986, to an unknown Brit named Lloyd Honeyghan.

Curry’s life had gone into a spin after the fiasco with Leonard and Trainer. By that point, Curry had alienated his camp. Gorman was shattered, feeling as if he had been betrayed by a son. Reyes felt shut out. Both men distrusted Muhammad.

“It was mass confusion,” Curry says. “I just wanted to get away from it. But I couldn’t. Every time I woke up or went to sleep, it was everything. It was like being in a war zone that never ended.”

For Curry, the issue finally became how to keep Gorman and hire Muhammad. Curry was the darling of the boxing elite but still hardly known outside of it. He blamed a lot of that on Gorman, who was portrayed in some circles as a backwater bricklayer who had exceeded his reach. Curry also was frustrated with his purses, especially after Leonard was guaranteed $11 million to fight Hagler. Meanwhile, people in Fort Worth questioned Curry’s loyalty, his snub of Gorman seen as a snub of his hometown.

Muhammad, on the other hand, came on as the hustling entrepreneur from Newark, New Jersey, that he was. His first boxing venture in the mid-seventies had been to buy the rights to Muhammad Ali’s famous tagline, “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee,” and put it on a T-shirt; a year later he merchandized the Ali Rope-A-Dope jump rope. He had gone to work for Arum in 1978 and learned the business inside and out, particularly the promotional end. He had always seen Curry’s endorsement potential as unlimited, and as proof, he landed Curry a $15,000-per-fight contract to wear Sasson boxing trunks. But when he left Top Rank to join Curry in 1986, some regarded Muhammad as a gold-digging opportunist. Curry, for one, was suspicious of Muhammad’s ties with arum, wondering whether they had really been cut and whose best interest Muhammad had in mind.

Curry says that he wanted only what was best for himself but that he didn’t want to hurt anybody, and somebody had to get hurt. “So I let it ride longer than I should have,” he says. “Things just prolonged. Even up to the Honeyghan fight.”

The Honeyghan fight turned out to be the grandest fiasco of all. By September 1986 Curry had fought only two rounds since beating McCrory nine months earlier and had put on weight in the interim. A week before the Honeyghan fight he still needed to drop ten pounds. Gorman, though still under contract, was exiled from the camp, and Muhammad was in charge. Muhammad found a nutritionist with a quick-loss diet, but as the pounds left, so did Curry’s snap.

It was obvious, however, that the weight was as much a symptom as it was the problem. Curry’s attention was scattered. At the press conference before the fight, no one wanted to talk about anything but a future Curry match with Hagler. Honeyghan sat there without opening his mouth. Curry was embarrassed, and when it was over, his friend Doug Jackson told him that if he had been Honeyghan, he would have walked out.

When Curry finally entered the ring against Honeyghan in Atlantic City, observers at ringside remarked that he looked gaunt. In Curry’s camp the previous week there had been discussions about canceling the fight because of the weight problem. But Curry, already inactive most of the year, decided to go on. When he was rocked by Honeyghan and nearly knocked down in the second round, it was clear that he was not in the fight. Curry knew it too, and he says that after the fourth round he realized it was over. After the fifth round, Reyes wiped off the blood that poured from Curry’s lip and kept repeating, “You’re not yourself, Don. You’re not yourself!” When the bout was stopped on a technical knockout after the sixth round, the TV announcers who called the fight were stunned. One boxing writer called Honeyghan’s win the biggest boxing upset in the last ten years, since Leon Spinks defeated Muhammad Ali. Ring magazine’s Bert Sugar called it one of the ten biggest upsets in boxing history.

I saw him in his seventh pro fight—I forget against who,” Larry Merchant, an HBO announcer, was recalling a few days before Curry’s bout in Las Vegas last April. “I remember calling a friend in Philadelphia and telling him I’d just seen a ten-million-dollar fighter. And I’d never heard of Donald Curry.

“But not unlike other tremendous talents in other eras, he has allowed the prize to get in the way of his fighting. He lost his grip a little. Boxers have a lot of time to stand around and do nothing, and there are always people out there to tell you you’re not getting enough money. It goes with the territory. But you can’t let it get in the way of what you’re doing. You only have a few years where you’re the absolute master of everyone, and if you spend those few years with distractions, you blow it.”

Merchant, who was standing behind Caesars Palace near the open-air boxing stadium that is boxing’s most hallowed venue, then did something as strange as hell: He shifted into the past tense.

“He was the rarest kind—an aggressive boxer,” Merchant said, clarifying the distinction between a boxer and a fighter and speaking about Curry as if stoking a memory. “He used his boxing in an aggressive manner rather than a defensive manner. Boxing is not a way to get away from punches but a way to establish superiority, without exposing one’s weaknesses. It’s what the greatest did.”

Back in his aerie atop the Union Plaza, his view like that of a command post above the casinos strung out below, Curry talks in the past tense too, but as a way into the future.

That future still looks good. Even as he speaks, the finishing touches are being put on his new $400,000 house, set on a breezy rise overlooking Lake Arlington. In another room is Curry’s fiancée, Valerie Cooper, an American airlines flight attendant. He hasn’t entirely committed to marriage yet (he has already canceled one wedding date), and he is not sure if he wants to do it while he is still fighting. He brings up those moods again.

His managerial situation seems to have leveled off. Muhammad is now his business agent, receiving about 15 percent of Curry’s purses, and Reyes is still his trainer. Gorman, meanwhile, receives a 6 percent cut for a role about as vaguely defined as it gets. Hours after Curry’s April win against Carlos Santos in Las Vegas, Gorman was spotted in a downtown casino, sipping a drink while his wife sat at a slot machine, both of them wondering if Curry was holding a victory party without them. Gorman, whose gym was closed temporarily in May for failure to pay back bills, remains suspicious of Muhammad’s ties with Arum. Since Muhammad took control, both of Curry’s fights were promoted by Arum (each for a $100,000 purse, Curry’s smallest reward in years), and the fight scheduled this month will also be promoted by Arum. “One of the things stated to Don is that I went along with Arum too much, to Don’s disadvantage,” Gorman says. “Well, it looks to me like the ball game’s in the field they wanted it in all the time.

In the ring Curry looks on track, though that too is inconclusive. Both of his fights since the Honeyghan loss (fought at 154 pounds) have ended in his opponent’s disqualification. Curry dominated both fights but wasn’t overwhelming. He does wear his added weight well, and more important, he seems to carry none of the scars that a loss like the one to Honeyghan can leave on a fighter. He is convinced that he wasn’t himself in that fight, and so in a sense he is convinced that he still hasn’t lost. “I’m ready to set my own path,” he says, repeating what has become his most familiar refrain. “I have to start over.”

As it turns out, Curry is starting over precisely, his fight against McCallum on July 18 coming a little more than a year after he was scheduled to fight McCallum for the same title. But instead of the $1 million he was guaranteed then, he will fight this time for less than half that. And this time, if he wins, it’s doubtful that Hagler or Leonard will be waiting for him. Another boxing axiom says that every great fighter needs a foil, and even if Curry beats McCallum, he may be left without one. Neither Leonard nor Hagler has made it clear whether he will fight again, but if either does, he likely will go up against the other or Thomas Hearns. Hagler and Leonard have each fought and beaten Hearns, a three-time champ, but those are Hearns’s only losses, and they give him the myth-building potential required for the big box office. That is a quality Curry is still trying to gain, and a win over McCallum could move him closer to it. “But the train passes,” arum puts in. “If you look at Hagler as the train, who else can make the big closed-circuit fight for Curry?”

It’s also obvious that although Curry may be Leonard’s equal inside the ring, he certainly isn’t his equal outside it. Leonard is shrewd where Curry is vulnerable, manipulative where Curry is sentimental, brilliant where Curry is bright. So Curry, while uniquely capable of grasping it, so far has found the biggest of big prizes just out of reach. He might be talented enough to get to it anyway. But as he has found out, there is a lot more to boxing than hitting and then trying not to get hit back.

“It seems like it’s taking a long, long time,” Curry sighs, aware of all that has been said. He really is a nice kid—pure Cowtown, in the ways that Gorman and Reyes and Doug Jackson are pure Cowtown: a little naive and isolated and slightly unequipped for the world outside their boundaries but still sure and somehow wonderfully organic. They all seem to be people too good to have been hurt the way they have been, like the tourists outside on the Strip heading for home earlier than they had expected.

“It seems like I’m right on the cliff, and ready to jump over it, and then the cliff keeps getting longer and longer,” Curry continues. Outside his hotel window, the sun is exposing a flyblown view of Las Vegas that the night and the neon tend to cover up. “Everything’s ready. I just have to take three more steps, and then it seems like the three steps keep getting longer and longer.

- More About:

- Sports

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Fort Worth