If there’s one thing I’ve learned living in Dallas for the past thirty years, it’s that we’re a very businesslike city. We’re not big on civic unrest. Whenever something happens that you might think will get our blood boiling—like the FBI raiding the offices of city hall officials or the head of the Dallas school district announcing that he overspent his budget by at least $64 million—we yawn and go back to work. We’re busy. Very busy.

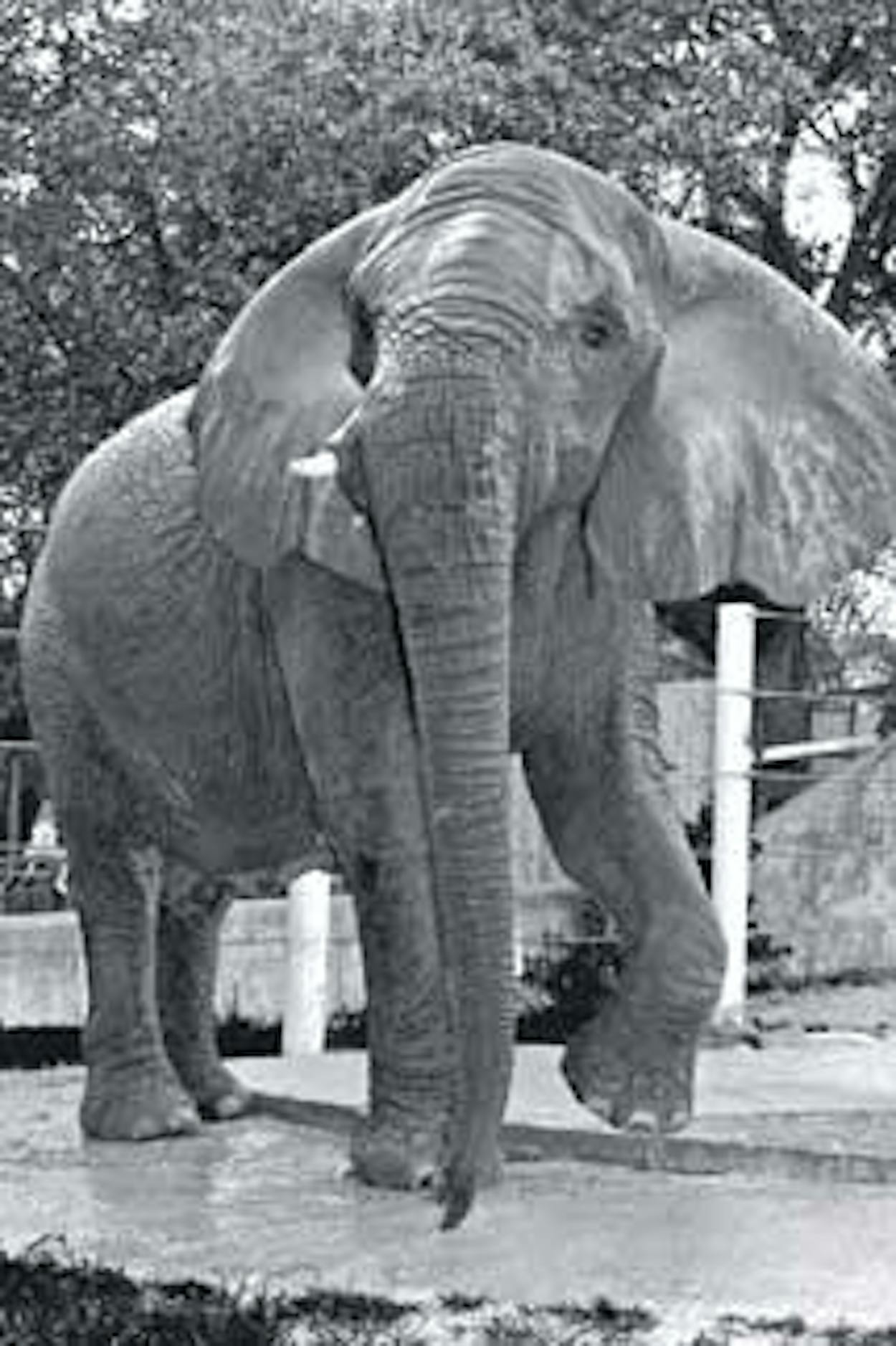

And then along comes Jenny the elephant. For the past two decades, she has been the star of the Dallas Zoo. She is a magnificent creature, 10,500 pounds, with deep-set eyes and a cute little tail that swishes back and forth. On a typical day, she knocks around giant plastic balls, bangs a barrel filled with fruit, and sprays water at her handlers. She lifts one leg and then the other in exchange for treats.

Still, it’s hard not to feel a little heartbroken for the old gal. For one thing, Jenny has spent all those years living in a cramped, barren habitat totaling only a quarter of an acre. It consists of nothing more than a concrete barn, a measly patch of dirt, and a small concrete pool. Sometimes she looks utterly miserable. She sways on her front legs for hours, which some elephant experts say could indicate stress or frustration. She stares forlornly into the distance with her trunk thrown over a wall. Over the years, according to zoo records, she’s rammed her head repeatedly into a wall and dug into her right rear foot with her tusk—“a sort of self-mutilation,” one of the experts told me. Jenny seems to be, well, depressed.

Then, this past May, Jenny’s companion, Keke, died from heart failure. After Keke collapsed, Jenny stood beside her for more than twenty minutes. She waved her trunk over the body and, finally, walked away, stricken with grief. Within days In Defense of Animals, a California-based group that keeps track of the country’s three hundred or so zoo elephants, issued a press release and posted a notice on its Web site, claiming that Jenny should be removed from her habitat. Like most animal rights organizations, In Defense of Animals believes that elephants—which are highly intelligent, intently social, and extremely mobile—should not have to live in zoos. Its goal is to move all zoo elephants into privately run elephant sanctuaries, where they can frolic untethered over hundreds of acres with other elephants.

One person who read the Web posting was Margaret Morin, a soft-spoken, middle-aged registered nurse from the suburb of Richardson. Morin is hardly an animal rights activist. “Sometimes on weekends I rescue stray dogs, and I feed a few feral cats at an office building near my job, which is not easy to do because I’m allergic to them,” she recently told me over breakfast, politely dabbing at her lips with a napkin. Nor does she often visit zoos because, as she puts it, “zoos tend to depress me.”

In truth, Morin had never laid eyes on Jenny. Yet upon learning that the 32-year-old animal probably didn’t have much longer to live—the average life expectancy of elephants in captivity is 33, half that of elephants allowed to roam free—she felt something stir inside her. “I knew right then I had found my cause,” she told me. “I was going to do everything I could to make sure that we show our appreciation to this beautiful animal and send her to a place where she could finally be happy.”

Morin created Concerned Citizens for Jenny, and she started calling zoo officials to discuss the elephant’s future. When she couldn’t get anyone to call her back, she decided to hold a rally. A few weeks later, she and fifteen other members of Concerned Citizens (most of them longtime friends) went to the zoo’s front entrance, where they held up signs that read “Free Jenny” and “Send Jenny to a Sanctuary.” “We will not forget you, Jenny!” shouted Morin, who, at that point, still hadn’t actually seen Jenny.

Perhaps because it was a slow news day, the Dallas Morning News showed up. And that’s when all the hullabaloo began. Morin started receiving calls and e-mails from other citizens who loved Jenny. Within a week, Morin had more than four hundred people on her e-mail list. Some of them were so inspired that they formed their own organizations: A young mother who for years had kept a photo of Jenny in her wallet started Concerned Families for Jenny, an SMU student started SMU Students for Jenny, and a woman who works for a Fortune 500 company started Concerned Professionals for Jenny. They began attending Dallas City Council meetings, hoping to persuade officials to move Jenny to the Elephant Sanctuary in Tennessee, which had already invited her to its three-hundred-acre area devoted exclusively to African elephants. And the groups held more rallies at the zoo and at city hall, with some of the most enthusiastic protesters wearing elephant suits.

Soon publications around the country were chronicling Morin’s fight. The New York Times—that’s right, the New York Times—sent a reporter to Dallas to write about Jenny. The headline read, “What to Do With Traumatized Elephant Stirs Up Dallas.” “Activists, Experts Locked in Battle Over Depressed Pachyderm’s Future” was the headline on the Web site for the CBS Evening News. “God, we look ridiculous,” one highly placed city official told me.

Although Gregg Hudson, the executive director of the Dallas Zoo, was flabbergasted that a woman who knew nothing about elephants had whipped up such a controversy, he could not deny that he had his own concerns about Jenny. When he first came to Texas, in September 2006, from the Cincinnati Zoo, he’d been dismayed to find her housed in an exhibit that had been built in the fifties. After Keke died he worried that Jenny’s mental state could worsen if she lived alone for a long period of time. When he had trouble finding another elephant to share Jenny’s home, he told his staff that the time had come to move her. But he believed the Tennessee sanctuary provided inferior care compared with the work of the Dallas Zoo’s elephant handlers and veterinarians. He decided that Jenny should go to the Africam Safari park, in Puebla, Mexico, a 617-acre drive-through zoo that contains a 4.9-acre area for elephants. Unlike the Tennessee sanctuary, Africam has been accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA), the umbrella organization for zoos in North America, which requires what Hudson told me was “the same kind of care that animals like Jenny get in Dallas.”

Needless to say, Hudson’s decision infuriated Morin and her fellow Tennessee supporters. “This is Jennygate!” Morin told me one day over the phone, in between her nursing assignments. She accused Hudson of pandering to AZA executives who allegedly don’t want AZA animals going to nonaccredited institutions. By July, a couple of Dallas City Council members announced that they too wanted Jenny moved to Tennessee. One council member, Angela Hunt, visited both the Mexican safari and the Tennessee sanctuary and returned to Dallas to proclaim the virtues of the one in Tennessee. Thirteen elephant experts from around the world signed a letter to Dallas mayor Tom Leppert describing the sanctuary in Tennessee as a “quiet, therapeutic environment” and denouncing the Mexican safari as distressful, claiming the sound of the cars and trucks passing by would upset Jenny and cause her delicate condition to decline.

So in late August, Hudson changed his mind: He announced that he was keeping Jenny in Dallas because he didn’t want to expose her to the stress of being loaded into a crate and moved a thousand miles away. The zoo, he said, would speed up plans to build a $10 million, four-acre elephant habitat to house Jenny and at least two other elephants, and he promised that the project, which originally was supposed to be built by 2011 as part of a new African savanna exhibit, would be completed a year earlier. He added that negotiations were already under way to get a second African elephant “very soon” from a private donor to share Jenny’s exhibit.

The announcement, predictably, led to even greater outrage. More residents joined the fight to move Jenny to Tennessee. They put “Save Jenny” signs on the sides of their cars and posted sentimental comments on a MySpace page in Jenny’s name. One woman with the screen name “earthchick” wrote, “Jenny’s in my heart and prayers!” Another woman, whose MySpace photograph showed her posing in a bathing suit, wrote to Jenny, “We love you!” Actress Lily Tomlin also got involved, filming two television commercials urging Dallas City Hall to send Jenny to Tennessee—“Her one chance to live in peace,” Tomlin intoned in a serious voice (not her “one ringy-dingy” voice).

Beverly Perry, the organizer of Concerned Professionals for Jenny, even wrote and recorded a song honoring Jenny, which she titled “Jenny’s Song.” “So leave your troubled life in Texas and find your healing in Tennessee,” wailed Perry, who was a member of a Christian band in Oklahoma in the late seventies. Jody Dean, a popular Dallas disc jockey for KLUV radio, played the song on the air and then made the fatal mistake of making fun of it, calling it “Butterfly Kisses” for a pachyderm. “I have to tell you,” he informed his listeners, “if Jenny is forced to listen to this song too many times, I think she might commit suicide.”

The station’s phone lines immediately lit up, with people referring to him as Satan, among other things. “I had female callers telling me they couldn’t put on their makeup because they were crying so hard over the beauty of the song,” Dean said. “One woman said she was crying so much she had to pull her car over on the side of the road so she wouldn’t have a wreck. I thought, ‘Uh-oh, we’ve got a bona fide elephant revolution on our hands.’”

Councilwoman Hunt is convinced that the zoo will not get the new elephant habitat built by the spring of 2010. “The one thing I’ve learned in my three years in city government is that most city construction projects get delayed for one reason or another, often for years,” she told me. “The idea that the city is going to design and build such a huge habitat in eighteen months is naively unrealistic at best and purposely misleading at worst.” Morin, who has seen Jenny in the flesh only once (she stood outside her exhibit for a few minutes and wept), says she cannot visit her again without “dissolving into tears.” She believes Jenny will not live long enough to see the new exhibit. “We’ve got to get her out,” she said. “And I will not rest until we do.”

I mentioned to Hudson that there would be hell to pay if Jenny died before she got a chance to walk into her new home. “People would never forgive you,” I said. He nodded and said quietly, “But we have four handlers working with her every day, and you would not believe how dedicated they are to her.” When I walked over to the elephant exhibit, right around closing time, two of the handlers were indeed in the concrete barn with Jenny. It was time for her “art session.” One of the handlers held a white canvas in her hands while another dipped two brushes into a can of blue paint. Behind her barred door, Jenny’s ears flapped and her eyes widened and she slapped her trunk excitedly on the pavement. She then grabbed the two brushes with her trunk and ran them back and forth over the canvas. Just as I had for the 22 years I’d been going to the zoo, I shook my head, marveling at the great Jenny while at the same time feeling sorry for her. “She’s going to be just fine,” said Karen Gibson, the head elephant trainer, handing Jenny two more paintbrushes. “I promise you, she’s going to be just fine.”