On June 8, 2003, a former Popeyes Cook from Houston named Cecil Viands’s died following routine spinal surgery at Vista Medical Center Hospital, in Pasadena. The cause was a massive infection. Under normal circumstances, Viands’s death might have been seen as a bit of horrifyingly bad luck, the sort of thing that happens to one unfortunate patient in a million. But luck had little or nothing to do with it. The immediate assumption in much of the local medical community was that Viands had died because of the incompetence of his doctor: an orthopedic surgeon and one-man surgery mill named Eric Heston Scheffey.

Viands’s death was only the latest episode in a long, grim tale of malpractice stretching back more than a decade. Scheffey had performed five surgeries on him since 1992. In complex and largely unjustified procedures that few orthopedists would ever have attempted, he’d methodically removed a large portion of Viands’s lower spine, taking out six vertebral disks, a good deal of bone, and alternately inserting and removing intricate arrays of screws, rods, bone-graft cages, and electronic growth stimulators. His activities went well beyond what consulting doctors had recommended or what the patient had authorized. In a single operation, he’d cut into Viands’ spine in seven different places—virtually unprecedented except in cases of severe accidents. He’d removed bone in order to decompress fourteen nerve roots—again, something most surgeons would never have even considered. According to an orthopedist who later reviewed the case for the Texas State Board of Medical Examiners, Scheffey’s surgical failure rate over those five surgeries was 100 percent. And almost all of them were entirely unnecessary. By the time the infection killed him, Viands was already facing life as a disabled person.

As disturbing as Viands’s case is, it was by no means unique or even unusual for Scheffey. There was Ed Gonzalez, for example, an auto body repairman from Humble who’d hurt his back lifting heavy equipment. Scheffey operated on him four times between 2001 and 2003, cutting out disks and bone and busily installing and removing hardware. After each surgery, Gonzalez’s back pain got worse. He is now unable to walk around the block, unable to sleep, and in pain 24 hours a day. He says that he might have killed himself if his father had not hidden his shotgun. A person identified only as B.P. in public records, a school custodian on whose spine Scheffey operated three times between 1998 and 2000, now has a condition called drop foot in which her foot hangs limply in a vertical position. She must wear a brace to walk. She has lost all bladder control and has to wear diapers. According to a later finding by a judge, not only did B.P. not consent to the surgeries, but they too were completely unnecessary. There is a long list of such people. Many, like B.P. and Viands’s widow, have sued Scheffey; many have not.

By almost any measure of medical performance, including the sheer number of his patients who are crippled, maimed, or in constant pain, Scheffey ranks as one of the worst doctors in American history. He is easily the most sued. Since 1982 he has had 78 malpractice claims filed against him, a total that does not count what one attorney estimates to be more than 150 people who would have sued him if they had not been beyond the legal statute of limitations or if lawyers had been willing to take their cases. He has settled 45 of those suits for more than $13 million. At least 5 people have died as a result of Scheffey’s surgeries, though doctors, attorneys, and former patients will tell you that the actual, unreported number is much higher. At least 4 of Scheffey’s patients have committed suicide because of the pain they were in or because of the depression brought on by the massive doses of narcotics the doctor prescribed or a combination of the two. One of those patients was so miserable that he committed suicide after he’d received a cash settlement from Scheffey.

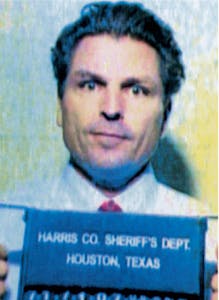

Oddly, Scheffey’s litigation-stained career has been anything but anonymous or low profile. It has been splashed all over Houston newspapers, magazines, and television news reports, which have been fascinated by his spectacular cocaine bust, in 1985, and by the multiplicity of lawsuits against him. There was also Scheffey’s flamboyant lifestyle, which featured multimillion-dollar mansions in River Oaks and Shadyside; a house full of expensive, big-name art; a collection of Ferraris; a private jet; and status as a favorite son of Houston’s art community. He has been the subject of five legal actions by the state medical board to either restrict or revoke his license. Viands’s death led the board to suspend Scheffey’s license in 2003. In February 2005, after 24 years, it was finally revoked, and he was fined $845,000.

Scheffey did not respond to several requests to be interviewed for this story, but if his own estimate in a deposition is correct—that his three thousand spinal procedures represented 20 to 30 percent of his total surgeries—then he may have performed eight thousand or more total operations on knees, ankles, hands, and shoulders, as well as spines. Yet what makes his story even more startling is that all were done with the explicit consent of a vast medical, insurance, and governmental bureaucracy, which, even after he became notorious for injuring patients, approved and funded every unnecessary surgery he did.

Like Viands, Mary Tywater believed she was going into the hospital for a routine operation. On the Thursday before Memorial Day weekend in 1985, Scheffey operated on the 43-year-old Daisetta housewife to remove several disks in her back and fuse several vertebrae. He was in the midst of that surgery when he lost control of her bleeding. Some four hours into the operation, Tywater was dead. There was blood everywhere in the operating room. The anesthesiologist’s report is nearly illegible because it is smeared with Tywater’s blood. Scheffey was 35 at the time, and this was the first fatality to take place in his operating room. But what should have been the unique horror of watching a patient bleed to death had seemingly little effect on him. He spent the holiday with his girlfriend and another couple at his large house in Baytown on Cedar Bayou. They rode golf carts around the property and drove golf balls into the water, went waterskiing, and swam in his pool.

Some four hours into the operation, Tywater was dead. There was blood everywhere in the operating room. The anesthesiologist’s report is nearly illegible because it is smeared with Tywater’s blood.

Scheffey was used to the good life, and his career can be understood as an ongoing, if highly unconventional, attempt to maintain it. He was born in Dallas in 1949 and grew up in an affluent family with a brother and two sisters. His father was a decorated World War II pilot and a successful lawyer who once ran for mayor of Dallas. The family was wealthy enough to buy Eric a Jaguar XKE for his sixteenth birthday. He attended W. T. White High School and then the University of Texas, graduating in 1972. He began his medical training at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston before transferring to the University of Texas Medical School at San Antonio and finishing in 1976. The year before, he had married Liza Goodson, a former Highland Park High School cheerleader from a well-to-do Dallas family. The marriage ended in divorce in 1979, for undisclosed reasons. He completed an internship and a four-year residency in orthopedic surgery at the Medical University of South Carolina. In 1981 he moved to Baytown, just east of Houston, home to the blue-collar industries that line the booming Houston Ship Channel.

Baytown, and east Harris County in general, is an orthopedic surgeon’s paradise. People who do manual work for a living are frequently injured, and their most serious injuries usually involve backs, knees, shoulders, elbows, and hands—the domain of orthopedics. Most of these people also carry generous amounts of state-regulated workers’ compensation insurance, which involves a sort of bargain between the laborer and the employer: A worker gives up the right to sue if he is injured in exchange for long-term medical care and disability benefits, including partial replacement of lost wages. Each year workers’ comp in Texas covers roughly 200,000 injuries, for which 240 insurers pay out some $2 billion in benefits. The workers themselves pay nothing, and there is no limit to how much medical care they can receive. Most of these patients have real injuries. But a small percentage engage in what is known euphemistically as symptom magnification (i.e., faking it or exaggerating pain) to take advantage of the system. It is a bitter irony that many of them ended up in the offices of Eric Scheffey, who would one day become the largest single biller in the program. In later testimony, Scheffey recalled that in Baytown his practice “took off like a rocket and continued along that vein. . . . A lot of workmen’s compensation patients predominated my practice and continued to do so, at least ninety percent.” Under workers’ comp rules, Scheffey was required to get a second opinion for every surgery. He always managed to find one.

He established his surgical practice at three Baytown hospitals: Humana Hospital Baytown, Gulf Coast Hospital, and San Jacinto Methodist Hospital. He was immediately popular. A strikingly handsome man, with olive skin, brown eyes, and a thick shock of dark, wavy hair swept back from a widow’s peak, Scheffey had a soft voice, a Texas accent, and a warm, engaging manner. His patients and colleagues found him friendly, charismatic, and very persuasive, particularly when talking a patient into an expensive surgery. In the words of one patient, he “could talk a monkey out of his last peanut.” He had a way of saying just the right things. According to Margaret Pieske, a former patient, Scheffey once held an X-ray up to the window, saying, “We’ll use God’s light.” “I immediately liked him,” she said, “because I thought he believed in God.”

Still, the hospitals where he worked soon started to notice his odd work habits. At San Jacinto Methodist, for example, he repeatedly canceled scheduled surgeries. He also failed to keep appointments with patients or keep accurate medical charts. Internal hospital memos from as early as 1983 show that the medical staff was worried that Scheffey’s erratic behavior might be the result of drug use. And he was not always the well-mannered and charming young doctor. In one nurse’s report from 1984, he was described as “very ugly and sarcastic toward me.” The nurse added that “his speech was very slurred and irrational.”

Still, the hospitals where he worked soon started to notice his odd work habits. At San Jacinto Methodist, for example, he repeatedly canceled scheduled surgeries. He also failed to keep appointments with patients or keep accurate medical charts. Internal hospital memos from as early as 1983 show that the medical staff was worried that Scheffey’s erratic behavior might be the result of drug use. And he was not always the well-mannered and charming young doctor. In one nurse’s report from 1984, he was described as “very ugly and sarcastic toward me.” The nurse added that “his speech was very slurred and irrational.”

Even more disturbing, Scheffey came to be known as a surgeon whose patients lost a great deal of blood. “The losses were massive,” says Priscilla Walters, an attorney who has been involved in twenty lawsuits against Scheffey. “Sometimes almost all of the patient’s blood had to be replaced. The surgeries he was performing, in the hands of a competent surgeon, did not result in much blood loss—usually about one hundred cc’s, or three ounces. One of my clients lost four thousand cc’s [more than a gallon] during a back surgery.” Scheffey so often emerged from the operating room covered with blood that he earned a nickname: Eric the Red.

Scheffey was woefully ignorant of one of the most important areas of surgery: hemostasis, or the control of bleeding. In depositions from lawsuits, two of Scheffey’s former colleagues said that since he did not know how to use conventional techniques to control bleeding, Scheffey resorted to primitive ones, notably the wildly liberal use of bone wax and Gelfoam sponges. Bone wax is a substance used to stop bone from bleeding. Gelfoam sponges are soaked in a coagulant called thrombin and are used to stop general bleeding. Most surgeons require less than one tube of bone wax during an operation. Scheffey often used ten. In a single operation, most surgeons might use one or two 5-by-7-inch Gelfoam sponges. Scheffey once used seventeen. “Since he did not know how to control bleeding, he used bone wax like Bondo,” says Hartley Hampton, a Houston attorney who has represented more than a dozen of Scheffey’s former patients. The application of bone wax in those quantities, according to a 1992 deposition from Dr. Baltazar Benavides, who had assisted in many of Scheffey’s operations, can create a breeding ground for bacteria that cause the sorts of infections that plagued so many of Scheffey’s patients.

Tywater’s death was thus a logical outcome of Scheffey’s incompetence. But it was also related to another of the doctor’s personal quirks. On the day after Memorial Day, a security guard at Montgomery Ward found Scheffey in green surgical scrubs, with shoe covers, a cap, and a lab coat crammed with $100 bills and reported that he was “pacing real fast, swearing and cussing, pulling things off the shelves.” Trailed by the security guard, Scheffey then went to the cash register and put eight toy dolls, four $100 bills, and his car keys on the counter and walked out of the store. Scheffey, as it turned out, was out of his mind on cocaine. Police later found thirty grams of the drug—about $3,000 worth—in his Jaguar. He was arrested, pled guilty to criminal possession of cocaine, and received a ten-year probation and a $2,000 fine. The state medical board restricted his license and put him on its own ten-year probation, which included drug tests, counseling, and the requirement that he be monitored by other doctors. Shortly after the incident, Scheffey checked himself into a California drug rehabilitation center.

The story, in all of its lurid detail, made the newspapers in Baytown and Houston. Though reporters never drew a direct connection between Scheffey’s arrest and the death of Tywater four days earlier, the two events were connected. In a later deposition, a doctor who had worked with Scheffey testified that the staff at the hospital where Tywater had died believed that Scheffey was taking drugs and that nurses had struggled to wake a drugged Scheffey in the doctors’ lounge just before he operated on her. Scheffey admitted in a medical board interview in 1986 that he had been using cocaine for eighteen months prior to his arrest.

His promising career quickly unraveled. Scheffey lost his hospital privileges at the three Baytown hospitals. The number of medical malpractice suits against him (including one from Tywater’s husband) was steadily rising, from one in 1982 to thirteen in 1986. By that same year he had, for the third time, flunked a test that would have made him a board-certified orthopedic surgeon. Meanwhile, word had spread in the tight-knit medical community that he was an inept surgeon who performed unnecessary surgeries. At the age of 36, he was a professional pariah. His career should have been over.

Until the early 2000’s, doctors in Texas were rarely removed for lack of medical competence by the Texas State Board of Medical Examiners. They were frequently reprimanded and probated, as Scheffey was, for substance abuse. They could lose their licenses for committing crimes (though at one point the state had nineteen felons practicing medicine). But they almost never had their licenses suspended or revoked for what is known in the industry as a “standard of care” violation. In fact, a doctor could be sued, as Scheffey was, dozens of times, and be the subject, as Scheffey also was, of wave after wave of complaints and still keep his license.

Which is exactly what Scheffey did. Only six months after his spectacular downfall, he even managed to find a hospital that would let him operate: a small facility in inner-city Houston called Medical Arts Hospital. Scheffey went to work there in November 1985, embarking on what would become the most productive, lucrative, and destructive phase of his long career. He was now cocaine free; his condition was monitored by frequent urine tests ordered by the state medical board. Whether this was good or bad news for his patients was debatable. A drug-free Scheffey quickly turned into a workaholic Scheffey. Almost immediately, he became the hospital’s main revenue producer, accounting for more than half of the patients at the hospital. His new private clinic in Channelview was soon jammed with people waiting for appointments. By the end of the decade, as many as ninety people a day would pass through his office.

A good example from that era was William McDuell, a Houston truck driver who came to Scheffey with a broken wrist. Scheffey operated on McDuell at Doctors Hospital-Airline, in Houston (where he received privileges in 1986), set the wrist, and had it put in a cast. Soon afterward, according to McDuell, his wrist “split open” from an infection. Scheffey operated again to fix the wrist and then somehow persuaded McDuell, who had merely mentioned to Scheffey that his leg had once locked up, to undergo back surgery in order to fix his leg. Scheffey performed the operation, after which McDuell was forced to stay in the hospital, in pain, for two weeks. Ten months later, McDuell was still in pain, and Scheffey operated again. This time McDuell’s back went numb, and he could neither get out of bed by himself or walk without falling. Scheffey operated a third time on his back, after which McDuell found that he could not swallow. A fourth surgery left him in constant pain, and he had been unable to sleep well since his ordeal had begun. When Scheffey then told him that he needed a fifth surgery, he consulted another doctor. (McDuell later sued, and Scheffey settled out of court.)

Why would Scheffey operate five times—or fifteen times in another case—when it probably wasn’t necessary? As far as anyone can tell, the answer was, very simply, money. He propped up his lavish lifestyle by performing anywhere between 250 and 350 surgeries annually, some of which could cost as much as $50,000 each. In 1988 he sold his house in Baytown and bought a twelve-bedroom, eight-thousand-square-foot, $2.75 million mansion on West Lane, in River Oaks. And while he ran his high-volume surgery mill out of his medical clinic—from which he took in more than $3 million a year—he plunged into the glittering social life in the heart of old-money Houston.

Why would Scheffey operate five times—or fifteen times in another case—when it probably wasn’t necessary? As far as anyone can tell, the answer was, very simply, money.

The next few years of Scheffey’s life are a testament to the fluidity of wealth in Houston and to the lack of social barriers for anyone with a great deal of money and a resolute willingness to throw it around. Tan, fit, rich, handsome, and extremely eligible, Scheffey began courting wealthy Houston women and was soon showing up in the society pages. He had a long relationship with socialite Francesca Bergner Stedman. According to the Houston Press, it led to the end of her marriage with Stuart Stedman, the grandson of real estate and oil tycoon Wesley West. Together they hosted receptions for the Houston Symphony and the Houston Art League and threw parties at his house. Scheffey was on the board at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston and gave generously to many local arts organizations. He socialized with the likes of art collector and heiress Dominique de Menil and arts patron Sue Rowan Pittman.

His lifestyle was not just lavish but quite public as well. His multimillion-dollar car collection was perhaps the best example of this. The July-August 1991 issue of the Houston fashion magazine Intrigue described the collection as “a dizzying array of red, white and black sports cars that includes seven Ferraris, a Porsche, and a BMW 750il.” They were all housed in a specially built, brick-paved, climate-controlled garage with mirrored walls. By all accounts, the interior of his house, which he had renovated over a seventeen-month period at huge expense, was stunning. “Dr. Eric Scheffey’s River Oaks house is positively jam-packed with eye-popping, mind-boggling, big-time, famous-name art,” gushed Houston Metropolitan magazine in the fall of 1991. That art included works by Frank Stella, Robert Rauschenberg, and Salvador Dalí. Almost every piece of furniture in the house—like the 1945 rosewood-and-aluminum Brunswick-Balke-Collender pool table—was special in some way. Scheffey, who was a music aficionado, had installed a $250,000 stereo system, which was featured in another magazine story. He also co-owned a private plane. To many people, it looked very nearly like a perfect life.

While the failure of either the Texas State Board of Medical Examiners or the Texas Workers’ Compensation Commission (TWCC)—which had to approve every surgery—to put a stop to Scheffey was ongoing, he didn’t entirely escape the notice of the medical community. In 1985 a Houston neurosurgeon named Martin Barrash began to see former patients of Scheffey’s and became alarmed at the condition that many of them were in. “I started seeing people with the most god-awful complications I’d ever seen in my life,” says Barrash. “One woman I saw had a piece of her ureter taken out during a disk [operation]. I had to go look in the literature. I had never even heard of it.…The patient’s belly filled up with urine. He didn’t know what the hell he was doing.” Barrash also says he saw patients who were, as he puts it, “plunged on,” meaning that Scheffey had slipped with a bone-biting instrument. The result: People being treated for minor back injuries ended up having trouble walking. “He would get in the spine and get lost,” Barrash says. Barrash became one of a very small group of doctors who both testified in malpractice suits against Scheffey and notified the state medical board about botched surgeries.

Many of the injuries Barrash saw over the years involved the spine. Scheffey’s hallmark operation was the spinal fusion in the lower, or lumbar, area of the back, which usually involves removing a ruptured, herniated, or severely deteriorated disk, installing a bone graft (usually from the pelvis) where the disk was, and securing it with screws and rods. While many orthopedic surgeons regard fusion at even a single level (there are five lumbar levels, corresponding to each vertebra) as something of a last resort, multilevel spine fusions were Scheffey’s principal source of profit. He would commonly do something that few other surgeons would, or even find necessary, which was to reoperate on a patient in order to remove the screws and rods he had put in. “Routine removal is medically unnecessary,” says George “Buddy” Tipton, an Austin orthopedic surgeon who testified against Scheffey before the medical board. “In all the cases I reviewed, he took out screws and rods for no reason. Even an experienced surgeon risks nerve injury, and that can result in permanent paralysis and loss of bowel function, bladder function, and sexual function.” There are other risks of fusion as well: The more the back is fused together, the more pressure there is on other disks and vertebrae and the greater the likelihood that those parts of the spine will fail or become unstable too.

The result for Scheffery was, by the early nineties, litigation on a scale that has rarely been seen. By 1995 fifty malpractice suits had been filed against him for unnecessary or incompetent surgeries, overprescription of drugs, and other issues related to his bizarre willingness to perform operation after operation on people who apparently did not need them. One of those cases was that of Pete Dunstan, whose 1988 lawsuit offered another window into the strange and lethal medical subworld of Eric Scheffey.

When he began treating Dunstan in 1985, the patient was a healthy, athletic 44-year-old whose only problem was that he had strained his back. Scheffey told Dunstan that a disk in his back was about to rupture and performed a three-level fusion. A few months later Scheffey performed a two-level fusion on Dunstan’s neck, this time telling him that another disk was about to rupture. The fusions failed, leaving Dunstan crippled and in constant pain. His condition at the time he left Scheffey’s care can be summarized as follows: He had atrophy and weakness in his right hand due to an ulnar nerve Scheffey had damaged and difficulty urinating. He was impotent, severely addicted to painkillers, in unremitting pain, and, according to his doctors at the time of his deposition, would never work again. Scheffey settled out of court with Dunstan for $2.6 million, but Dunstan’s crippled, pain-racked condition suggests a reason why two other Scheffey patients in those years, Benny Norton and Charles Webster, committed suicide. (Both families sued Scheffey.)

By the mid-nineties Scheffey had already been deposed an astonishing ninety times, but the videotapes from some of those sessions offer few hints that he felt any remorse. When challenged, his approach was almost always to retreat into medicalese, droning on for hours about the more technically complex points of his surgeries. One video deposition from 1992 is typical: Scheffey, with a guardedly neutral expression on his face, answered questions with a sort of impenetrable, emotionless objectivity. He conceded nothing. One of the few press interviews he ever gave (to the Houston Chronicle, in 1995) suggests a deeply adversary cast of mind: “They [insurance companies] set out on a plan…They have kept me in hot water with the board with complaints about patients,” he said. “They managed to have me sued a number of times in such a manner that it made it difficult for me to get malpractice insurance…” Scheffey backed up such claims by mounting his own legal attacks against those whom he perceived to be harming him. He sued Barrash for slander three times. He sued an insurance company, whom he said had slandered him, winning a whopping $11 million in 1993. He also sued the media that had covered him, including NBC and the Houston Press, whose 1992 “Eric the Red” story was harshly critical of him. The Press settled out of court.

Yet none of his legal trouble seemed to deter Scheffey or make him change his behavior. His biggest problem was finding anyone to insure him at all. In 1993 he had appealed to the state Commissioner of Insurance to force the Texas Medical Liability Insurance Underwriting Association to suspend a surcharge they had imposed on him that would have required him to pay $537,931 in addition to his usual premium of $63,286. Such a surcharge meant that the insurance company would be charging $601,217 for what amounted to $600,000 of insurance. Scheffey lost the appeal. If state regulators had not quite figured out who Scheffey was yet, the insurance companies certainly had.

Where were the regulators? Why, with so many lawsuits filed, a track record known to a large segment of the medical community in Houston, and continual coverage in the press, was he allowed to continue performing surgeries in the state of Texas? In 1989 the state board had filed an informal complaint against the doctor based on a long list of patient injuries and other problems collected by Barrash, who by now was spending a good deal of time trying to expose Scheffey. But it was not until 1993 that the board mounted a full-scale, heavily-documented effort to revoke Scheffey’s license in an administrative law court. Hearings in that case coincided with news of yet another Scheffey disaster: In 1994 his patient Ancel “Bud” Freeman, who had gone in for his third back operation, lost four quarts of blood and died after a seven-hour surgery. In 1995 a judge did what everyone expected: She recommended that Scheffey’s license be revoked, not just for malpractice but also for excessive charges. But the board ignored that recommendation and voted instead to give Scheffey a five-year probation that would let him continue to practice but with some restrictions: To operate, for instance, he would have to have a written consultation from another doctor. “I was extremely distressed and disgusted at the board’s action,” says then—executive director Bruce Levy, whose staff mounted the case. “I came close to resigning.”

Scheffey immediately appealed the ruling in a state district court and won a temporary injunction. Later, the court reversed the board’s decision, allowing Scheffey to proceed as though nothing had happened. It was not until 1997 that an appeals court reversed the district court, but by then Scheffey’s probation had less than three years to run. It is likely that Scheffey had started to believe, with good reason, that his medical license was legally invulnerable.

Thus began what amounted to a second professional golden age for Scheffey. In the late nineties he went to trial with five lawsuits and won them all, including one by the family of Freeman. The number of lawsuits filed against him dropped: From 1997 through 1999 only three suits were filed; from 2000 to 2002 there were only six. And he was making more money than ever. According to filings in one lawsuit, Scheffey’s gross income from his practice in 1998 was $4,032,292. By 2002 it had risen to $5,453,361. Four entries from his 2002 profit-and-loss statement suggest the sort of life he was leading: Entertainment and meals: $238,927; Legal [fees]: $259,013; Travel and convention: $389,419; Charter expense [aircraft]: $448,260.

In the wake of all the bad press in 1994 and 1995, however, Scheffey had begun to lose friends in River Oaks, especially in the old-money set. “Oh, this guy was playing big, trying to date girls of the old Houston circle,” says a woman who runs in those circles but asked not to be identified. “The problem was that old Houston never liked him and was always suspicious of him.” Says Houston Chronicle society columnist Shelby Hodge: “People absolutely stopped seeing him. People cluck-clucked all the time, especially in the medical community.” But in 1999 Scheffey had done something that had greatly improved his social standing: He’d married a young society woman named Kendall Thomas, who was eighteen years younger than he was. She was pretty and well connected and part of the younger social set in River Oaks. A year before he married her, he had moved into a $5.8 million, ten-thousand-square-foot house on Longfellow Lane, in Shadyside, near Rice University. The place was so spectacular that its landscaping and elaborate flower beds were featured five years later on the cover of Texas, the Houston Chronicle’s Sunday magazine.

With Kendall there were parties and social invitations, even though many people wondered, as one acquaintance put it, “what she was doing with him.” He never quite made it back inside: “I went to a party at their house, one of those art groups,” says the friend. “I just remember that it was a big party with big money but kind of sleazy people. Girls with surgeries, like they might have had a background in exotic dancing. You know what I mean.”

In one deposition, a Vista nurse said that Scheffey would often have two operating rooms going at the same time.

Through all this tumult, both social and professional, there is no evidence that Scheffey altered even a small part of the work behavior that had caused him so much trouble. It seemed that Scheffey’s practice had never operated quite so efficiently, relying upon an elaborate network of enablers that included fellow surgeons, nurses, radiologists, anesthesiologists, and a system of insurance and workers’ comp approvals that was easily gamed. The TWCC, which, in effect, controlled 90 percent of his revenue, not only allowed him to continue but failed to challenge him when he was asking for approval (in one case, for the fifteenth surgery on one patient). Once the TWCC approved it, there was little anyone could do.

Scheffey had also found the perfect home for the sort of work he did: a facility in Pasadena called Vista Medical Center Hospital. Vista was owned by a publicly traded Houston company called Dynacq Healthcare, whose main line of business was high-volume surgery. Dynacq, in fact, made both the Forbes and Fortune lists of the one hundred fastest-growing companies in 2002 on the strength of its astounding 47 percent annual growth rate over a three-year-period. In a 2003 article in Barron’s, company spokesman Jim Baxter boasted that “a very active surgeon might be able to do five spinal surgeries in a day.” It is unclear if he was referring specifically to Scheffey, but he may as well have been. In one deposition, a Vista nurse said that Scheffey would often have two operating rooms going at the same time. So dependent was Vista on Scheffey that when his license was later suspended, in 2003, his absence would lead to dropping profits that had a direct impact on Dynacq’s bottom line.

Vista was also remarkably undiscriminating in whom it allowed to use its facilities. In 2001 Vista became the last hospital in Houston (of twenty at one time or another) to let Scheffey operate. According to a 2004 report by the Texas Department of State Health Services, Vista not only failed to check on its doctors’ records and on lawsuits against them but also knowingly allowed Scheffey to perform surgeries in 1999 and 2000 as the main surgeon and without a monitor, in violation of his probation. In response to a detailed and lengthy written query from this magazine, Dynacq spokesperson Christina Gutel would say only: “Dr. Eric Scheffey was licensed by the Texas State Board of Medical Examiners during his tenure at Vista Medical Center Hospital. As soon as that board suspended his license, his surgical privileges were revoked at Vista Medical Center Hospital.”

All the while, of course, the list of Scheffey’s victims only grew longer. In 2001 he’d operated on Thomas T. “Buddy” King after King had injured his back in a truck accident. Instead of the four hours the operation was supposed to have lasted, it took fourteen hours. King lost large amounts of blood. When it was over, he had severe pain in his legs. On the third day after the surgery, on his way to the bathroom, King dropped dead of a blood clot. Another patient, Jennifer Springs, was a fast-food cashier who had injured her back in a fall in 1995. Scheffey had operated on her back eight times between 1996 and 2001, telling her that if she did not have the operations, she would eventually be unable to walk. She got worse and worse, at one point staying in the hospital for three months. She now has severe leg and back pain, far more intense than when she started out. She can walk only short distances. Patient Mary Garcia lost a large amount of blood in a 2002 operation on her back. Now she too has severe pain in her legs and back, can’t sleep because of the pain, and can walk only short distances. She will never be able to work again. She sued Scheffey last year. “I try not to take too much pain medication,” she says. “I prefer to cry.”

With such a constant flow of patient complaints, Scheffey ought to have attracted (yet again) the attention of the state board. But the lesson of 1995 was that, even if the board mounted a large and competent case, it was still impossible to get rid of Scheffey for reasons of malpractice. In 2002 Dallas Morning News reporter Doug J. Swanson published a sweeping indictment of the medical board as an incompetent, do-nothing agency. “It has refused,” wrote Swanson, “in the last five years to revoke the license of a single doctor for committing medical errors.” Nothing was different at the workers’ comp commission either: The agency still resolutely refused to throw out bad doctors.

That finally began to change at the state board under president Lee Anderson and new executive director Donald Patrick. In 2002 the number of informal “settlement conferences”—where doctors come before the board to defend themselves against complaints—rose from 172 to 477, the number of disciplinary actions jumped from 187 to 277, and the financial penalties more than doubled. Budgets increased. Government funds flowed. Bad doctors had their licenses taken away for standard-of-care violations. “We, the agency and the board, began to see our mission differently,” says Patrick. “There is a lot of fearlessness, because we’ve got nothing to lose. We said, ‘Let’s do as good a job as we can to try to protect the people of Texas,’ because we were aware that we had not been doing that.” The same thing was happening, at a much slower pace, at the TWCC, where medical adviser Bill Nemeth had instituted an “approved doctor” list, prompting howls of protest from the Texas Medical Association, the doctors’ trade association.

Taking out Scheffey was one of the reformers’ top priorities. In 2003, after the death of Cecil Viands, Scheffey’s license was temporarily suspended by the state medical board. The following year, the board brought a second case against him that was based on 29 surgeries on 11 patients and the testimony of 6 surgeons. On the recommendation of that court, Scheffey’s license to practice was revoked in February 2005. He has appealed it, though it seems unlikely that he will win reinstatement.

Though Scheffey would not comment for this story, his longtime lawyer, Ace Pickens, said he felt that there was no basis for either the revocation of Scheffey’s license or for the $845,000 fine. “If you look at the Board of Medical Examiners’ records for administrative penalties over the last five years,” Pickens says, “[and] you add them all up, it would not amount to this one case.” He also pointed out that almost all of Scheffey’s surgeries had been supported by second opinions: “They took eleven patients, ten of whom had been subject to second opinions, and said that second opinions by board-certified orthopedic surgeons were no good and that the surgery should not have been performed. Even if that is so, at least he went through the system and should be given the benefit of the doubt. He did not go about maliciously performing surgery. He got a second opinion for everything he did.” Pickens, who has known Scheffey for more than twenty years and says the two are friends, also vouches for Scheffey’s character. “Dr. Scheffey has absolutely been a lightning rod because he is an advocate for patients,” says Pickens. “He is a good man. I don’t believe he is an ogre or that he is evil.”

Scheffey now appears to be completely out of business. Two months after his license was revoked, a corporation he owned called Harris County Bone and Joint Clinic Association pled guilty to a third-degree-felony charge of “securing execution of a document by deception”—fraudulent billing—and paid penalties of $25,599. He sold his mansion in Shadyside and moved back into the smaller mansion in River Oaks, where he still officially resides and where he was served with litigation papers as recently as April. According to Harris County records, he still faces roughly twenty malpractice suits, all filed since 2000. Though he was recently investigated by the FBI for workers’ comp fraud, the agency says that that investigation is now complete. It produced no indictments. In its 2004 complaint, the state medical board also charged Scheffey with practicing medicine with a suspended license, a third-degree felony punishable by up to ten years in prison. According to the complaint, Scheffey continued to practice medicine even after his 2003 suspension, using his partner Dr. Floyd Hardimon as a front. When the board temporarily suspended Hardimon’s license later in 2003, it did so in part because it found that Hardimon “associated with and aided and abetted [Scheffey] in the practice of medicine after [Scheffey’s] medical license had been suspended.”

In the absence of any criminal charges, Scheffey is, remarkably, free to do everything but practice as a doctor. There is little doubt that he has an enormous amount of money. The talk among the Scheffeys’ old social crowd in River Oaks is that Eric and Kendall have purchased a home in Geneva, Switzerland, where they have moved with their two children. “One day Kendall called me and said, ‘We are moving to Geneva. Here is my number. Please call,’” says one friend who asked not to be identified. “She said, ‘People are so mean-spirited. We are sorry we are leaving on such a negative and sour note.’” But very likely not as sorry as patients like Mary Garcia and Ed Gonzalez. Indeed, one of Scheffey’s hallmarks is his ability to move blithely through his life, as though there were not an enormous trail of human wreckage behind him. And he feels no apparent need to hide or disappear into anonymity. Friends say that he and Kendall rented a big house for the summer in one of the richest and most celebrity-filled resort towns in America: Aspen, Colorado.