This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

You need twenty bucks—fast—but you don’t have anything socked away, your friends and relatives won’t even talk to you about money, and your credit rating isn’t good enough for a cup of coffee. What do you do? You swallow your pride, take something you’re not too attached to, and hustle down to the first pawnshop you can find. Granted it’s not very romantic or dignified, but it can be the least painful way, sometimes the only way, of getting cash in a pinch.

That’s the way most people are first introduced to pawnshops: through cruel necessity. For some, that first loan becomes a lifelong cycle of pawning and retrieving. Others keep coming back for the fun of shopping the odd lot of pawnshop merchandise.

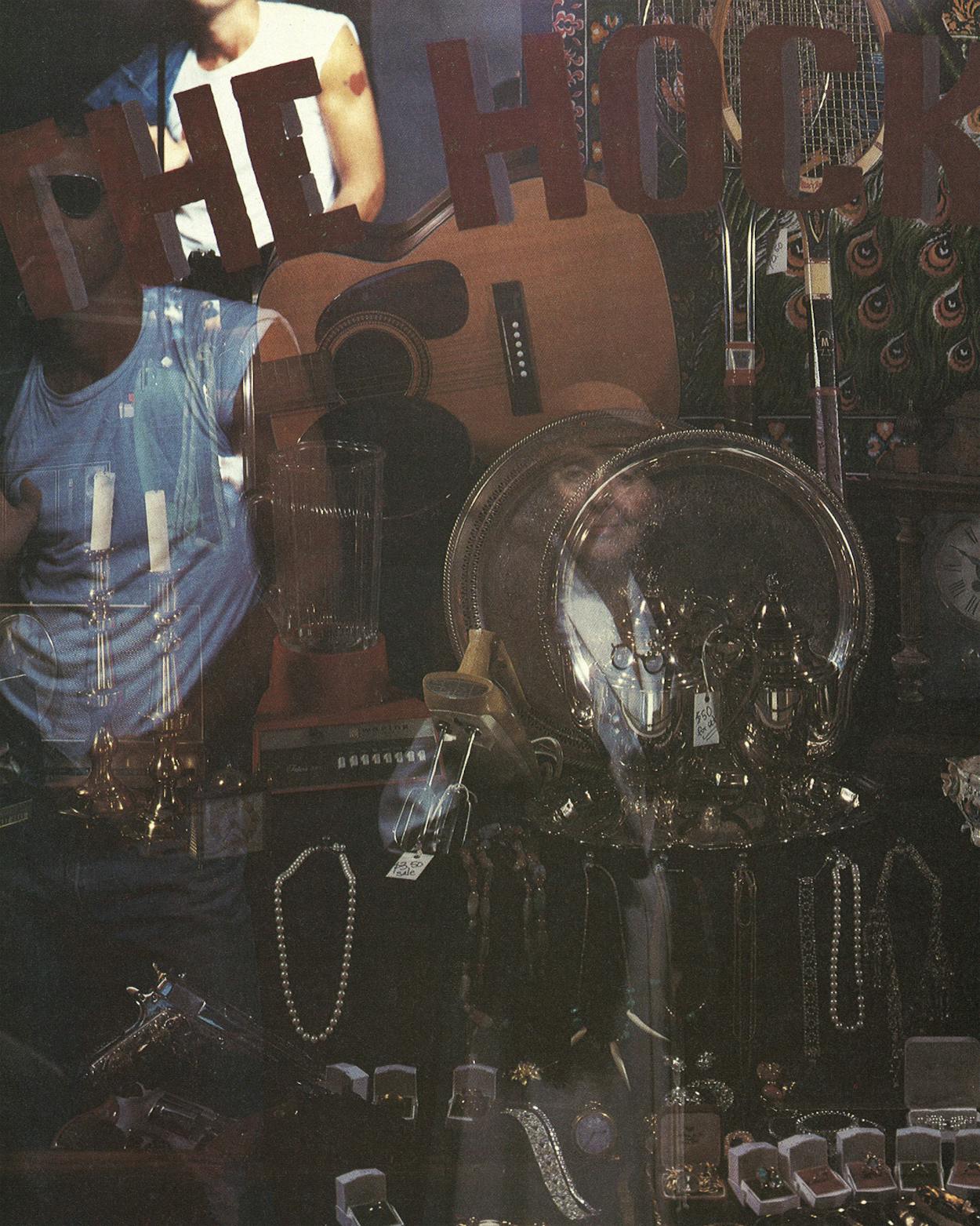

For most middle-class people, pawnshops are fascinating because of their slightly sleazy, even dangerous, connotations. They’re usually in seedy parts of town, next door to adult bookstores and raunchy bars. They’re reputed to deal in stolen goods, and they’re frequented by people who need quick money for God-only-knows what nefarious purposes. E-Z Pawn Shop manager Arnold Blomdahl of Austin recalls, “Every once in a while we get customers who have never been in a pawnshop before, and they really are jumpy. There was this lady who brought her son in to look for a tennis racket. She was dripping in diamonds and very nervous. She obviously thought somebody was going to jump out from behind a counter with a gun.”

The truth is that pawnshops are a lot less dangerous than you might imagine. In fact, they fit right into the mainstream of American culture. Ingenuity, business savvy, turning a quick dollar, helping folks who are down on their luck—who can deny that these are qualities that have helped make America great? When it came to winning the West, pawnshops were right in there—along with saloons, houses of ill repute, and banks. In fact, it’s doubtful that the frontier could have been tamed without them.

“ ‘I once got stuck with a casket. It sat around for months. Then a man came in looking for a coffee table. I told him I didn’t have any, but I did have a coffin table. He thought that was really funny and he bought the casket.’ ”

—Michael Keefe, pawnbroker, Killeen

To understand pawnshops, you have to keep in mind that a pawnshop is two symbiotic organisms: a loan company and a retail store. The collateral (that is, the pawns) for the loans provides the merchandise for the store. Neither could function without the other.

Oddly enough, however, the largest loans bring in the least money. Interest rates (which are set by state law) escalate in a way that is highly beneficial to the pawnbroker but discouraging to the customer. If you want $300 to $2500 in a hurry, you will pay only 12 per cent annual interest, which is a lower rate than many people pay on a bank loan (and less than the pawnbroker has to pay on a loan at his bank as long as prime interest rates stay where they are). As you might have guessed, pawnshops don’t make many loans over $300, even to long-standing customers. If you need between $100 and $300, you will pay interest at the rate of 30 per cent annually until you retrieve your item. If you want $30 to $100, you’d better be ready to pay a whopping 180 per cent annual interest on your pawn. But—buckle your seat belts—if all you need is less than $30 and you hock your Instamatic, you will pay 240 per cent annual interest on the loan to get the camera back. Most pawnshop transactions are culminated within far less than a year, so the actual amount of interest doesn’t add up to much, but the sheer percentages are staggering.

These interest rates have a lot to do—understandably—with pawnshops’ bad image. Even the untrained observer can deduce that a pawnbroker can make a lot more money lending twenty-five bucks in four separate deals than a hundred dollars in one. That’s why, if you try to pawn your Nikon F, no broker is likely to give you more than $100 for it. It’s not that he doesn’t know the value of the camera. He simply is not interested in 30 per cent interest rates. Under the circumstances, you would be better off pawning a single lens instead of the whole camera.

Discouraging expensive pawns is good for the retail side of a pawnshop business too. Brokers need to maintain a large and diverse selection of merchandise; if they make too many large loans and tie up their money in a few items, business tends to suffer. Even if a customer were desperate and willing to pay 240 per cent interest on a $1000 pawn (which the broker is prohibited by law from charging), most brokers would still prefer to take in ten small items instead of one big one.

What happens to an item once it’s pawned? Surprisingly, 65 to 80 per cent of all pawn loans are paid off and the items redeemed. The high rate of retrieval is due to the fact that most of the loans are small; not only that, the item is usually worth considerably more than the money loaned. If an item is not redeemed within sixty days of the maturity date (one month, maximum, after it is pawned), the broker has two options: he can put it on the shelf with a price tag, or he can leave the ticket open and allow more interest to accrue. The previous owner can still get his possession back (if someone else hasn’t grabbed it first) either by paying the retail price or by forking over the loan, plus interest. Despite the hefty interest rates, the customer is usually better off repaying the loan; it’s still less than the retail price, since the pawnbroker offered him only a fraction of the item’s value to begin with, in order to collect a higher interest rate. Because it’s usually not too expensive to retrieve a pawn (provided it hasn’t been left for a long time), pawnshops do a lot of repeat business. In fact, most say they have at least 50 per cent repeat business, both on pawns and pawners. Several older, established shops claim three to four generations of the same families have done business with them.

As pawnshops go, though, four generations barely qualifies as recent history. Known in the Orient and ancient Greece two thousand years ago, pawnshops are even mentioned in the Bible. The Book of Job warns the godly not to take a widow’s ox as a pledge. In Europe, pawnshops have been around for over seven hundred years. Early public pawnshops were short-lived because of modest interest rates; the private ones were more successful. In 1462 a Franciscan monk began the first charitable pawnshop in Perugia, Italy. Other so-called “banks of pity” (montes pietatis) were established throughout Europe, and by 1515 they had been endorsed by Pope Leo X, a member of the Medici banking family. Other respectable people found pawnshops handy on occasion. Queen Isabella offered to hock her jewels to finance Columbus’ trip to the New World. (Luckily, she didn’t have to.) Four and a half centuries after Isabella’s generous offer, pawnshops have spread into every nook and cranny in Europe and America. Mexico, for instance, has a seminationalized operation headquartered in Mexico City.

No one knows for sure where the infamous three gold balls, a symbol for pawnshops worldwide, originated. They may have come from the balls on the Medici coat of arms, but merchants of Lombardy used a similar sign, and some say the balls represent coins. Whatever their origin, it’s certain that the balls today symbolize anything but a charitable enterprise. Most of us don’t think of pawnshops as philanthropical for one very good reason: they aren’t. Charity just happens to be where the roots lie. It obviously didn’t take too long for a concept with such potential to be recognized by men of vision. Hence the traditional three-orbs joke: “Two to one you don’t get it back.”

The biggest single draw for most pawn customers is the speed and ease of the transaction. If the amount is small (say $100), you can get it immediately and save the time of hassling a bank, or being hassled by one. In fact, the pawnshops are essentially the poor man’s bank. There’s no waiting, no intimidation, and you don’t have to dress up or worry whether your breath spray will last. The pawn is a basic, clean, and simple transaction: “I need $20. You can have my radio until I pay you back.” Most pawnbrokers say that the quick pawn will never die because it takes at least twenty minutes longer to get money from a bank.

Even so, a lot of pawnshops have felt the impact of the big bank credit cards. Visa and Master Charge lured a lot of customers out of the shops because their rates are uniform, they require no collateral, and they are quick. Unfortunately for the pawnbroker, this was an affluent group of customers. A salesman who traveled a great deal, for instance, would frequently carry a ring or watch to hock in case he ran short of funds on the road or needed to buy dinner for someone to clinch an unexpected sale. Now all he has to do is make sure he has a credit card and he can leave the jewelry at home.

“ ‘After UT played in the Cotton Bowl one year, two of the players came in and stood around until everyone left. Then they pawned their Cotton Bowl commemorative watches. I took both watches. Sold them for a good price, too.’ ”

—John Nissen, pawnbroker, Austin

Pawnbrokering is big business in Texas. There are over seven hundred pawnshops operating in the Lone Star State, several large chains among them. Dallas has 90, Houston 80, San Antonio 35. Pawnbrokers in Killeen, where forty shops are located in thirty square miles, say their area might have the highest concentration in the world. Why Killeen? North America’s largest single military installation, Fort Hood, is right down the road, and all manner of cameras, radios, stereos, and watches purchased cheaply overseas by enlisted men eventually find their way into the shops.

By all reports, the pawn businesses in Texas is growing, and, like most businesses, the mom-and-pop operations are slowly disappearing as chains like the Texas State Credit Company (with fourteen shops across the state) expand. A manager of one of the chains said, “Places like ours will eventually put the small shops out of business because they don’t have the cash backlog for the loans.”

The big chains are the pawn businesses of the future for several reasons. First, they are almost never out of money, and that is the cardinal principle of a brokerage. If one store runs short, its manager can simply order cash from another one. Second, and this is probably the clincher, with several stores in a city, merchandise can be switched so that each one has what its particular customers will buy. Jewelry from a less prosperous store might be sent to a well-to-do area where it can be sold for more. Guns, on the other hand, might be transferred to a store located in a tough neighborhood. This flexibility and cash flow explain why the chains generally do better than the single-store operations. Of course, there are exceptions. One independent pawnshop in downtown Houston has seven employees (not including the owner) who make more than $50,000 a year each. Obviously, there are big bucks in the business for a well-run single store, even if most of the money comes from relatively small transactions.

Another trend in the business is a movement toward a strictly retail operation. Some shops carry new merchandise as well as pawns, and it’s likely that more may find it advantageous at some point to forego the pawn business altogether. The newer pawnshops are also sprucing up their operations, and many are now almost indistinguishable from any small retail store. Suburban customers are attracting pawnshops to more affluent parts of town, and nowadays any section of a city with high-density apartment complexes will have one or two pawnshops not far away. Lewis-Nathan’s in Houston is almost indistinguishable from a nice jewelry store and caters to a rather wealthy clientele, which only goes to show that nobody ever gets too rich to turn up their nose at a bargain.

Although this upscale movement is smart from an economic standpoint, the truth is that the new shops don’t seem to have the variety, or the tawdry mystique, of the older shops. Another thing they lack, with their squeaky clean image, is the shadowy figure of the old-style pawnbroker, a character whom few people know and even fewer want to know. And who can blame them? After all, pawnbrokers get lousy PR. How many of the countless brokers featured in the weekly TV cop shows are good guys? Not many. They are usually portrayed as a little sleazy at best, and more often as sly, cowardly scavengers involved in the underworld and dealing in stolen goods. This, unfortunately, is the view that sticks. Even some pawnbrokers half believe it and will go to great lengths to avoid mentioning their profession outside the store. They are always either “in the jewelry business” or “have a retail operation” or some other vague phrase. Of course, some of the more successful brokers do in fact have other businesses, but they needn’t be so apologetic about the pawns, because the truth is that it’s fairly difficult for pawnbrokers to be involved in fencing stolen merchandise. A copy of every pawn ticket is turned over to the local police, and pawnbrokers are required to record the serial number, if any, of the pawned item. In most instances, the pawn ticket is checked through the police computer against theft records. If the serial numbers match, the broker loses, since the police return the item to its owner and he’s out the amount he paid as a loan. As a result, a customer is more likely to buy a “hot” TV at a secondhand store than from a pawnshop.

Stolen goods sans serial numbers—such as jewelry and sporting goods—is another matter, because they are difficult if not impossible to trace. Pawnbrokers usually jot down only short descriptions like “lady’s single-stone diamond ring,” and city police haven’t the time to check such sketchy information on several thousand pawn tickets a week against lists of stolen diamond rings. Still, fewer pawnbrokers than the media would have you think deal in stolen merchandise or are even aware that an item is hot. Of course, this doesn’t keep pawnbrokers from making money, and quite a few in Texas have six-figure incomes.

If pawnbrokers turn out, on close inspection, to be less menacing than their traditional image, so do pawnshop customers. All kinds of people shop the pawns, not just junkies and second-story artists. If you stand around long enough in a pawnshop, you will lose many of your illusions about the average customer, because there is no such thing. At a shop near a military base, everyone from buck privates to COs comes in. Near a college, there are students, professors, staff, and hangers-on. Even housewives shop the pawns, which is hardly surprising when you consider that a pawnshop is really nothing more than a supersized garage sale. Broker John Nissen of the Texas State Jewelers of Austin remembers that one year, after UT played in the Cotton Bowl, two of the players came in. “They stood around until everybody else had left. Then they pawned their Cotton Bowl commemorative watches. I took both watches. Sold them for a good price, too.” About the only people who don’t shop the pawns are farmers, because even in Texas, the pawns are an essentially urban phenomenon.

Although pawnshops by their nature deal in a variety of goods, certain ones cater to specific interests. There are shops for musicians, gun collectors, antique buffs—almost any type of interest if the market is large enough and the money right. The trick is to find the one or two that deal in merchandise that appeals to you and shop them regularly. If the shop owner gets to know you, he’ll even hold things for you when they come in so the noontime crowd doesn’t snap them up. Sometimes it’s fun to go in even if you aren’t in the market for anything in particular because you never know what astounding thing is going to show up. Larry Coffman of 439 Pawn in Killeen recalls, “I took in a casket once. I don’t remember the circumstances of the loan, but I got stuck with it. It sat around for months. Then a man came in looking for a coffee table. I told him I didn’t have any but I did have a coffin table. He thought that was really funny, and he bought the casket.”

And so it goes. Once you get to know the pawns, you’ll find them both less and more mysterious than you imagined: less mysterious because much of their purported danger and underworld aura is pure myth, and more mysterious because every item in them has a personal history. Who knows what compelling necessity or dastardly deed might lead some poor soul to hock a casket? Not even the pawnbroker knows for sure.

No Big Deal

When is a $300 camera not a $300 camera? When you’re trying to pawn it.

This is my Nikon. It has been a lot of places with me, and I’ve taken a lot of pictures of my friends with it. My father-in-law bought it for me in 1972 in Tokyo for $289.58. Today it is easily worth between $300 and $350 with its 28mm f/1.9 Vivitar Series 1 lens. An equivalent new model would cost twice that amount.

Out of curiosity I decided to see how much collateral my camera would translate into at the shops in Austin, where I live. Here’s what I found: (1) “One hundred bucks. That’s the most we can give.” (2) “Fifty dollars.” (3) “One hundred dollars. I could give you more if you want to sell it.” (4) “Sixty bucks. Too old. People these days want the light meter inside the camera.”

I was a little discouraged after the first four offers, but decided it was just my usual luck, hitting the worst first, so I forged ahead: (5) “Seventy-five dollars. There are too many cameras on the market.” (6) “Fifty dollars. We have too many cameras already.” (7) “Seventy-five dollars. It’s pretty old.” (8) “Fifty dollars. We really don’t deal in cameras too much.”

By then I really felt bad. Maybe the message is Don’t try to pawn anything you care about, because nobody else thinks it’s worth as much as you do. The pawnbroker isn’t necessarily trying to cheat you by offering a low price; it’s just that experience has made him expert in pinpointing the value of used goods. He can’t stay in business long by guessing. He knows. And almost any pawnbroker will tell you that few Nikons are left unredeemed. It’s not good business for him to offer a lot.

Just remember one thing: don’t pick a day when you’re feeling low to see what your possessions will bring in cold cash at your local broker’s, because the net result will definitely put a few holes in your security blanket. It did in mine.

M.H.

For a Few Dollars Less

Amy Vanderbilt never told you how to behave in a pawnshop, much less what to buy. We do.

Some people know how to barter and some don’t. If you get sweaty hands and feel like you are insulting the seller’s integrity by offering him less than he’s asking, there are few real bargains for you in the pawnshops. On the other hand, if you enjoy a good haggle, you’ll be in your element. Just remember one rule: Never talk about the item’s value. This puts the broker on the defensive. Instead, talk about what you can afford: “Listen, I’m really short on cash because I just had to pay for brain surgery on my poodle. But I really want this stereo, so here’s what I can do. . . .’’ You get the idea. Most pawnbrokers are inveterate horse traders. As one owner said to me, “I don’t like to come down more than fifty per cent when I’m bargaining.”

Whether or not you’re a natural haggler, there are still quite a few good buys if you know what to ask for.

One of the biggest surprises is tires. Apparently, many new car owners feel their chances of having a flat are slim enough to rationalize pawning the spare. Getting a matched set of tires does present a problem, but if you are industrious and go to ten or twelve shops, you can probably find four for a popular car like a Chevy Monte Carlo for between $8 and $20 a tire.

Common to pawnshops everywhere, jewelry still affords a lot of bargains. A reputable broker will allow you to have an appraisal made on any jewelry you are seriously interested in. You either make a deposit, bring an appraiser with you, or have a representative of the pawnshop accompany you to the appraiser’s office. If you really look honest, the broker might let you borrow the piece if you leave identification, but don’t count on it. Although prices vary, most jewelry in pawnshops costs a little above wholesale.

In almost any pawnshop, sporting goods make up a fair portion of the merchandise. The shops near universities are the best bet for sports equipment such as tennis rackets, but you will find golf clubs almost anywhere. Don’t ask me why, but apparently there is a nearly unavoidable link between playing golf and pawning your clubs.

Very few would-be pawn shoppers realize it, but tools are a real bargain. What makes them a good buy is that in many cases they are guaranteed by the manufacturer. It doesn’t matter, for instance, where you buy a Craftsman wrench. If it breaks, Sears will gladly exchange it for a new one and ask no questions. While some tools are available anytime, others tend to be seasonal. The best building tools are available in the worst building seasons, as you might expect.

Lots of bargains for first-time customers can be found among the abundance of small appliances in pawnshops. All types of blenders, mixers, toasters, and irons are available. You might even find two identical products with different prices simply because the broker has more money invested in one than the other.

Justify music lessons for your kid with an inexpensive musical instrument from your local broker. Saxophones, trumpets, violins, flutes, piccolos, almost anything that can produce a note will turn up in the pawns. It’s distressing to think that for each instrument, there must at one time have been a musician to go with it. Most instruments are priced fairly low, presumably because the previous owner gave up in disgust and sold cheap, and there are good bargains for the knowledgeable buyer.

Loans have been made on the slimmest of collateral, judging from the amount of pure kitsch that shows up in the shops. With only a little bit of searching, grotesque and wonderful things can be found: fake deputy sheriff badges, switchblade combs, mid-fifties radios, engraved cigarette lighters, naked lady ballpoint pens—there is something to inspire every collector’s lust. After all, where else could you find a full-length painting of Elvis Presley on black velvet, framed, and for only $27.50?

Firearms are a staple of the of the pawn system, but, ironically, guns probably have given brokers the worst PR. Almost any shop will have cheap, inferior handguns, but some specialize in weapons, and careful scrutiny will turn up precision armaments ranging from Colt .45s to some very exotic military hardware. The presence of guns probably accounts for the fact that, according to the owners, pawnshops are often burglarized but seldom robbed. It’s just too risky.

One word about real deals: You probably won’t find any. The few killer deals are usually the result of an error in judgment by the pawnbroker or, more often, his employees. For instance, a friend of mine recently purchased an $800 flute for $35, but that kind of find is a rarity. Most likely neither the person who sold it nor the pawnshop employee who took it in knew the value. This situation doesn’t occur often, though. Most of the time you have to drive your own bargains.

M.H.

- More About:

- Business

- TM Classics

- Longreads