In the old days the season started in mid-November, around the peak of the rut, but for a long time now opening day has been moved back to the first Saturday. Some years we need the woodstove, other years the air conditioner. Cousins, fathers, brothers, uncles, grandfather—for a week we live in the Hill Country bunkhouse built by us in the broiling spring and summer of 1987. The roof gets pounded by marbled hail, and for those of us sleeping on the upper bunks, our faces grow chilled by each night’s frost and our hair stands on end during the electrical storms that cause the tin to crackle. On balmier nights the branches of overhanging oaks scrape and scratch against the roof like the sound track of an old horror movie.

My father’s father, Old Granddaddy, found this property via an ad in the newspaper up in Fort Worth. It was the heart of the Depression, but he was a young man and wanted a place in the Hill Country where he and his family could go hunting. He came down here and checked it out, decided to take the lease—what was it, a dime an acre for a thousand acres? Who knows? He said yes. He changed our lives.

Relatives of Davy Crockett had once owned it, and before that, Comanche claimed it. Judging from the incredible density of tool shards scattered here and there—arrowheads, spearheads, ax blades, awls—I believe it was as special to them as it is to us. On one mesa, I found lichen-spattered sandstone rocks arranged in a perfect circle, the size of a tepee ring, with a view of the entire Hill Country. Lower down, at the mouth of one of the canyons, there are fantastic granite monoliths, eroded into visages eerily reminiscent of the giant heads at Easter Island, and other boulders loom in the shapes of elephants, rhinos, clenched fists.

Now and again you will encounter an old, blue-tarnished bullet casing. The dozen or so men in my family who have hunted here every year since about 1935 have fired a lot of shells. Even if we shot only a couple of times a year, that would still add up to almost two thousand bullet casings breech-jacked into the brush, cartwheeling gold-glinted through the sun, to be lost for a while, until joined by another, perhaps decades later, landing in the same location.

Over time, the deer tend to be drawn to the same landmarks—passing through the same slots and ravines and trails, often at the same crepuscular hours. By learning so well the shape of the land and the timing of the deer as they pass across it, we have found a curious way of slowing time down, or at least bending it, like a blacksmith forging an iron wagon wheel, into something less linear, something that moves in an arc or, for all we know yet, ultimately a full circle.

The more deeply I have come to know this place, the more I understand that there is a reassuring sameness everywhere. The green translucence of each sunfish in the little creek casts a delicate fish-shaped shadow when sunstruck, so much so that the shadow seems more real, more visible, than the fish themselves. A hike through the high boulders on the east side of the lease—boots scritching on the pink wash of gravel that is the detritus of the decomposing granite—takes me past the crystals of quartz that lie next to the bleached skull of a wild hog. The teeth and savage tusks, loosened from his jaw, appear in their repose no different from the bed of ivory crystals on which he now rests.

Elsewhere, on the same hike, far back in the brush, I encounter the skull of a bobcat, with its formidable rabbit-killing canines still intact, resting amid a mound of dried rabbit pellets. Who controls whom, predator or prey? I suppose we should be more intent on finding and killing deer, but we have killed so many across the decades. It’s not so much that there’s a truce as there is a desire, finally, for everything to move more slowly—to move as slowly as possible—and as we all know, when you kill a deer, the hunt is over. At this stage of our lives, we are all less eager for the hunt to be over.

A close observation of nature cannot help but yield a poetic sensibility, and who observes nature more closely than a hunter? Not all hunters, however, evolve (or devolve) into poets. Certainly Old Granddaddy did not. He remained a resolute slayer of deer all the way to the end. After a stroke at 87 damaged his shooting arm, he learned to shoot left-handed and continued his life’s harvest, uncomplicated, it seemed, by questions of mortality, or even jeopardy, chain-smoking cigarettes around the dry cedar all day. An eater of fried foods, particularly pork—“I never see a pig I don’t tip my hat”—he probably would have lived to be about 120 had he had even remotely better habits. He’s gone now, though steadfastly we each and all follow him.

Hunting demands presence and attentiveness, makes life electric with possibility. Even as we age and lose the fire for killing and procuring—as if made weary by our relentless success—the habit of attentiveness continues. We observe the regularity of patterns, from the four seasons to the phases of the moon to the cycles of the deer in the fall breeding period, and everything in between. And yet the hunter’s eye stays ever watchful for the anomaly, the unpredictable bright spot amid the comfortable patterns of the familiar.

This ability to be two things in the world—pattern-viewer and anomaly-seeker—has sharpened who we are as a species and as individuals. I think that stories serve the same purpose within a family. Each year we retell so many of the old ones even as we seek new ones. Many of them concern pranks. Again and again we fall happily to the retelling of these gone-by moments, like the time long ago when a cousin, who shall remain nameless, killed a big rattlesnake and decided to bring it back to camp to skin and fry and see whether it really did taste like chicken. The snake was rendered headless for safety before being tossed into the back of the truck and onto a pile of firewood. It was dark by the time this nameless cousin returned, and he straightaway asked his brother Randy for help unloading the vast scramble of limbs and branches.

Always an enthusiastic worker, Randy seized a big armful, branches splaying every which way, and as he was walking over to the fire, his face so close to the branches that he could barely see where he was going, I inquired innocently, “Say, is that a rattlesnake in there with all that wood?”

Randy refocused on the immense snake that was in the midst of his load and threw the wood into the sky with a most satisfying scream.

Another time, I found myself heading back to camp alone, well after dark, without a flashlight. There was no need for one—we know every inch of the tangled thousand acres, better, I think, than we know the canyons and corridors of our own minds—and walking along in the darkness, still far from camp, I began to smell propane, potent as a spill. I was passing the creek beneath the high canopy of live oaks that form a long, eerie tunnel, and a short distance ahead, I saw the spot of light that was the source of the scent: Randy with his hissing gas lantern. He’s too old-school to use a flashlight—he likes the farther and more democratic throw of the lantern for his night-walking—and as I watched his lantern drifting through the all-else darkness like a firefly, a plan came to mind, one too good to pass up.

Knowing that he could hear nothing over the wailing hiss of the lantern, I ran down the dark trail after him, drawing up just inches behind him. Spanish moss hung in looping tendrils from the canopy. I took in as much air as I could and let loose with the loudest panther scream I could muster, then jumped back out of the sphere of light as he dropped the lantern. The globe cracked and the mantles crumpled, but the twin burners kept jetting orange firelight.

He sat down promptly—in that tiny sphere of light, he looked pale and sick—and he peered wild-eyed into the darkness. “Richard?” he said quaveringly. That was twenty years ago, and those days are gone; all our hearts are too frail and worn-out now for such shenanigans.

It isn’t just Randy who is the target of pranks; we all are. No one escapes. One year Russell, another cousin, shot a nice eight-point down in the creek. I had heard his single shot (“One shot, good shot; two shots, maybe; three shots, bullshit” went Old Granddaddy’s mantra), and I knew he’d been successful. A few moments later, I saw a nice little fork-horn slipping through an opening on the other side of the creek, illuminated by the mid-morning sun on the side of Buck Hill.

It was a long shot, but I had a good brace and was confident; I made the shot, and the buck dropped instantly. I climbed down out of the rocks, crossed the creek, ascended Buck Hill, cleaned the little buck, and then, feeling strong, began dragging him back toward camp, as had been done in the old days, rather than going to get a truck.

I had dragged it for only about fifteen minutes before coming through a clearing and seeing Russell’s much larger buck, also gutted, hanging in a tree; he had already gone back to camp for a truck. His was a very nice buck, and I had no qualms about untying it from its limb, hiding it in the bushes, and replacing it with mine.

I then continued on to camp, where Russell was regaling everyone with the tale of his big deer. We were all excited to hear about it, and he was proud to show us, so after lunch we drove out there in a caravan.

It pleases me to recall the confusion with which Russell slowly approached the deer, the disbelief in his face, and the way he turned to us slowly and said, “This is not my deer.”

“Oh, Russell,” my father said, “they always look bigger when they’re in the woods.”

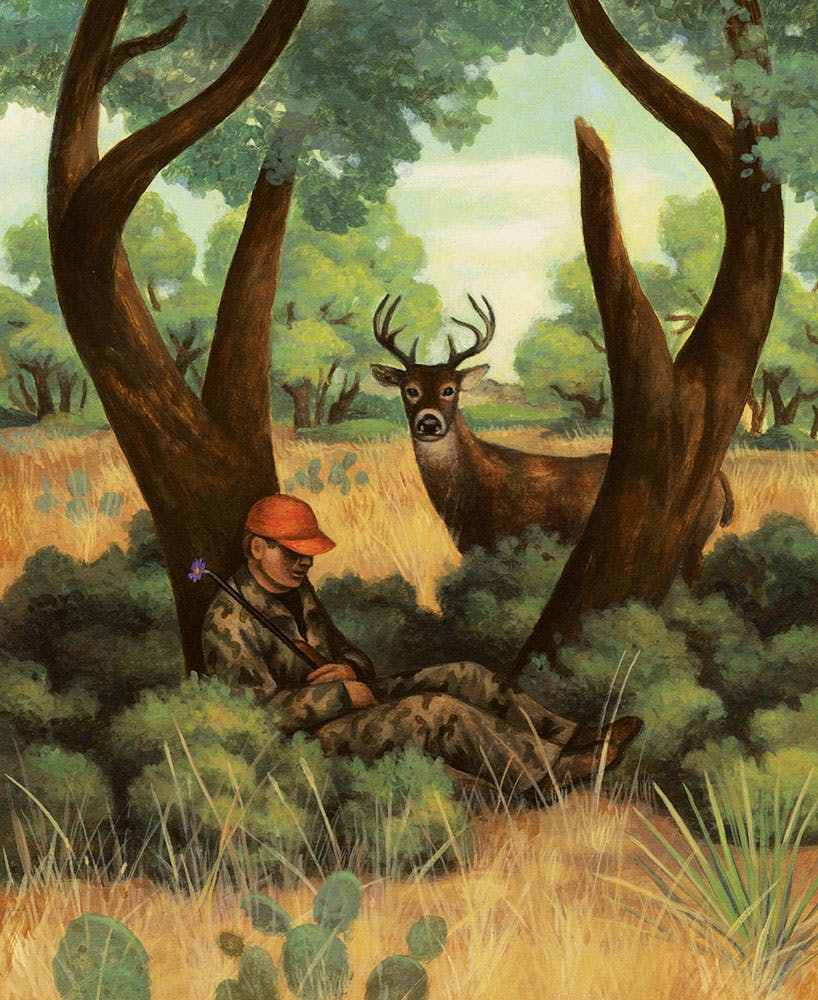

Other times we’re far less brutal. As we age, we take mid-morning naps more and more often, and our hearing is no longer keen. It’s easy to sneak up on one another. We’ll spy someone dozing against the trunk of a tree, camouflaged within the ground shrubbery of agarita or shin oak, and we’ll slip right in and place a wildflower—a late-season aster—in the gun barrel, then pass on, unaccounted.

We used to kill deer like crazy. They were drawn to us as if by our desire alone. We seemed to know the day before—the night before—where we would see the deer. It was not with confidence or arrogance that this certainty impressed itself on us but instead with a kind of wonder. Our yearning for prey was incandescent, something ancient and holy, and we never took such dreams for granted. We marveled at them, and the next day we moved toward those places—those appointments, those rendezvous—with the surety of faith.

And when the deer appeared, in much the manner we had imagined, we were grateful, never boastful. We understood that the success of such ventures never depended on our skill but was always instead the decision of some larger thing, some larger force—something a little like the electricity created by the confluence of our desire, the landscape, and the deer, as well as the world’s need to keep on moving.

Those kinds of dreams no longer occur. A central strand of the electrical current—our desire to find deer—has gone cold and silent. Instead, now we sit quietly among the oaks and cedars. Sometimes the deer pass by us anyway, and sometimes—unless it is only my imagination—they almost look confused, as if wondering why their world has tipped and where the hunters have gone. We admire the morning sunlight in their eyes. We admire the smooth grace of their muscles. They have been here far longer than we have. They may or may not outlast us. Watching them pass by, it is easy to imagine that it all goes on forever, that the current in which we once so enthusiastically participated will last even longer than the hills.