When you ride shotgun with Willie Nelson around the back roads of Willie World, the self-contained universe he created for himself and his extended family in the Hill Country west of Austin, you realize what it is that makes him such an icon.

It isn’t his recording career, which spans five decades and has produced more than a hundred albums, hundreds of singles, and dozens of gold and platinum records. They include Red Headed Stranger, the gritty Old West song cycle that put him on the musical map; Stardust, his collection of pop standards, which has been on Billboard’s charts for more than 570 weeks; and Wanted: The Outlaws, the first country album to go platinum.

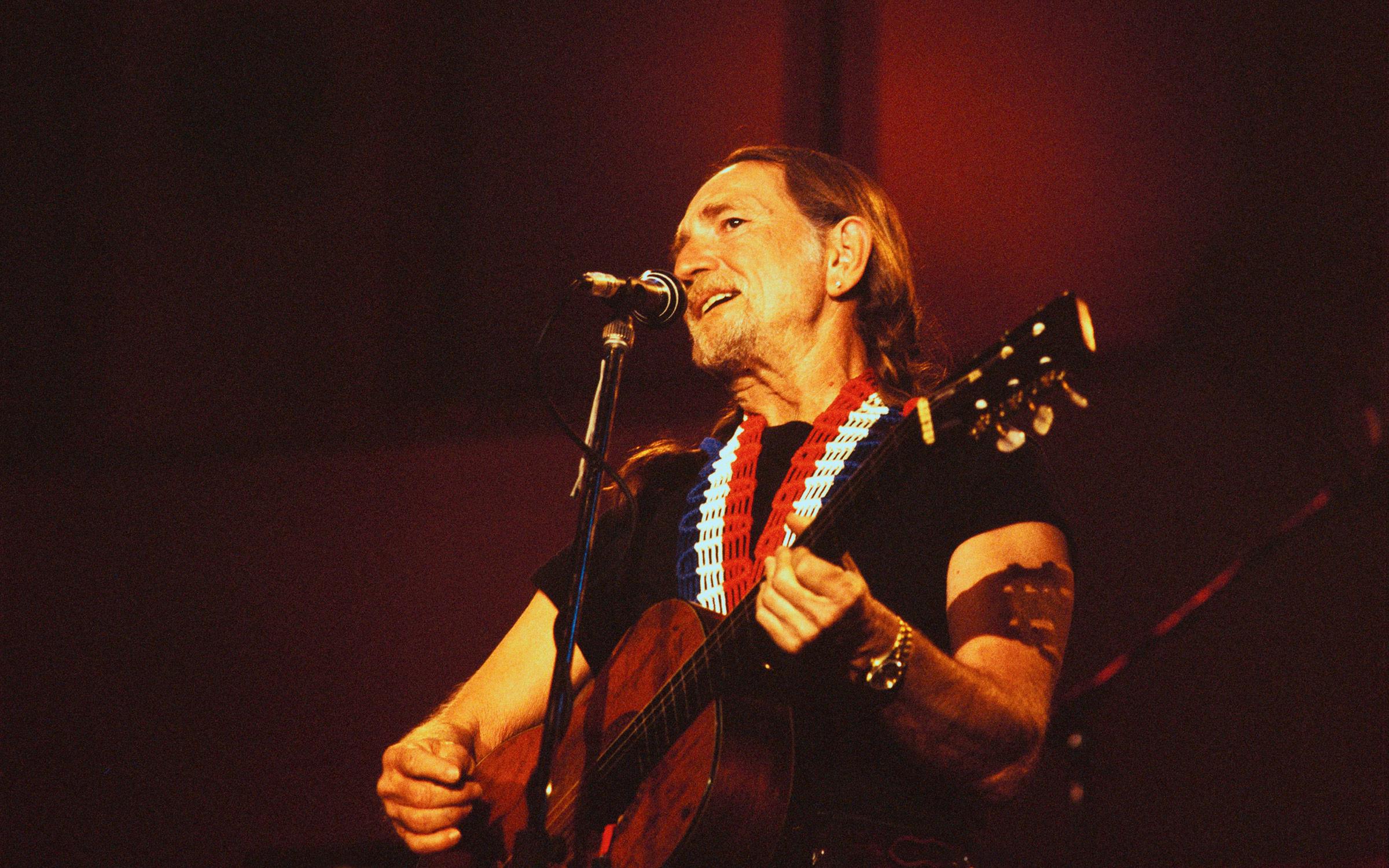

It isn’t his plaintive voice, which is as pure and clear as springwater and as unmistakably Texan as a singer’s could ever be, tinged with jazzy hepcat inflections.

It isn’t the soulful notes plucked from what must now be the oldest, most battered instrument in show business, in a fingerpicking style that sometimes stretches into Django Reinhardt Gypsy territory.

It isn’t his peculiar talent of putting words together in rhyme to tell a tale, as he did on “Family Bible” (the rock-solid gospel anthem that belongs in every church hymnal) and “On the Road Again” (which, thanks to Charles Kuralt, has become the official anthem of American wanderlust).

It isn’t his second career as an actor—his starring roles in films like Songwriter, his bit parts in Wag the Dog, Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me, and other recent fare, and his occasional TV appearances, notably his recurring gig as a U.S. marshal on Doctor Quin, Medicine Woman.

It’s his Willieness. It hits you while watching the old guy in black with the scraggly beard and the puppy-dog eyes undo a braid on his pigtail. He doesn’t fit the stereotype of a 66-year-old veteran of a profession that eats its young. The goofy grin he flashes conveys the vibe that he really and truly likes what he’s doing. We like it too. Raised in the heart of the state and steeped in its ways, coming up the hard way and going against the grain, he’s a Texan’s Texan. He’s seen the wilder side of life and isn’t uncomfortable in the company of thieves, a few of whom have been his friends and business associates (that’s Texas too). A little bit honky-tonk and a whole lot cosmic, he’s a cultural evangelist who knows how to lead a flock of true believers—a technique that serves him well in Vega or Vegas, whether he’s washed in the neon glow of a beer joint or basking in the klieg lights of the great performance halls of the Western world.

Through it all, ol’ Will grins away. As he tools around in his pickup truck in a state of herbal bliss, he’s locked in a zone of his own and right in sync with the master plan hatched at age eight. “I started out watching Gene Autry and Roy Rogers every Saturday on the movie screen in Hillsboro [ten miles north of Abbott, his hometown],” he says in his relaxed drawl. “I knew what I wanted to do: I wanted to be a singing cowboy, ride my horse, play my guitar, shoot my gun. So here we are.”

Willie Hugh Nelson is nothing if not consistent. Our little drive began in his Western town, Luck, Texas (“Either you’re in Luck, or you’re out of Luck”), a movie set where he and his buddies get together and hang out and sometimes dress up as cowboys and roll the camera, blazing pistols and all. After we pass the stables, where he keeps his horses so he can saddle up whenever he’s not touring (which is hardly ever), the singing cowboy recounts his most recent episodes. “We had a great bus ride the other night. I don’t know if you were down in Houston watching the Astros [at the last regular season baseball game in the Astrodome], but we did ‘Turn Out the Light, the Party’s Over.’ I met Nolan Ryan, sat there, talked to him for a while. Right after that, we got on the bus, went to Tempe, Arizona. We played the next night. Got back on the bus and come all the way back to Austin. We got in two days ago. Last night we went over here to Poodie’s Hilltop [Poodie being Poodie Locke, Willie’s roadie for life, now semi-retired]. So we’ve been busy for the last, uh, sixty years.”

The nightlife may not be a good life for most folks, but it’s the only life as far as Willie’s concerned. He enjoys riding on the burnished brown Prevost bus with the “Comanche at Sunset” mural on the side so much that he sometimes sleeps in it when he’s off the road. “We used to stay in town every night,” he says, “but I couldn’t find anybody the next day to go to the next town. We’d turn thirty people loose in Chicago or New York City at midnight and say, ‘Okay, we got to leave at ten in the morning,’ but at ten in the morning you can’t find anybody. I was the same way: I’d get in all kinds of trouble just by staying over. It takes all the temptations away if you get in the bus and go to the next town.”

Temptations aside, Willie has managed to have the sort of effect on society that befits an artist who was honored by the president of the United States at the Kennedy Center. He’s redefined the meanings of “family” and “picnic,” made Austin a music hub, become a folk hero through his battles with the Internal Revenue Service, and given of himself generously for what he thinks is right, whether raising money to restore the fire-damaged courthouse in Hillsboro, championing the legalization of hemp, or standing up for the family farmer at his annual Farm-Aid concerts.

The only entertainer who came close to matching Willie’s impact in Texas was Bob Wills, the leader of the Texas Playboys and the king of Western swing, a sophisticated dance music that was invented here in the 1920’s and remains popular today. Not surprisingly, a whole lot of Wills rubbed off on him. “I know every Bob Wills song,” Willie says. “He was a fantastic bandleader, very charismatic. When he walked on the bandstand, everybody gelled. I liked the way he worked. He’d play ‘San Antonio Rose’ and people would hit the dance floor and dance. As soon as the song was over, he’d count to four and go right back into it again—he’d play the same song twice. They loved it.”

Eventually Willie got to play with Wills. In fact, since his first gig at age ten, as a sideman in John Rejcek’s Bohemian Polka Band in Abbott, he’s worked with just about everybody: Frank Sinatra, Julio Iglesias, Luciano Pavarotti, Ray Charles, B. B. King, Bob Dylan, George Jones, Dolly Parton, Lefty Frizzell…

Is there anyone left?

“Streisand,” he chuckles. “We could do a Hank Williams duet together.”

Somewhere in a faraway city, a record company executive is rushing Barbra the sheet music to “Hey, Good Lookin’.”

Four dogs with wagging tails are waiting for him on the porch as he parks the pickup next to the World Headquarters in Luck, an old-timey saloon with a satellite dish on the roof, a fully stocked bar, and a movie screen with church pews for seating. The walls are adorned with Willie posters, Willie album covers, and snapshots of Willie with friends like Richard Pryor and Johnny Bush. There’s even a photo of Willie with his cowboy hero Gene Autry.

His buddies, a casual, semi-grizzled bunch partial to gimme caps, jeans, and running shoes, gather around the J-shaped bar while their boss eats his eggs and beef bacon. And when he’s done, he vanishes out the side door by the back of the bar, just like Autry used to do in the movies. “Well, here I go,” Willie says. “It’s time for my favorite thing to do: Gotta go get my picture taken.” He tries to make it sound like a burden, but his complaint rings hollow. He walks a hundred yards to the Opera House, where a photographer and his assistants are waiting. He sits on a stool in a makeshift studio, quiet, patient, occasionally flashing that goofy grin, doing what needs to be done, giving the photographer all he wants. The photographer looks like he’s having the time of his life, and so does Willie, and so does everybody else milling around Luck. It’s the Willie Way.