Michael Dell’s mantra these days is “be direct,” so I decided to take him up on it. “You and I are a lot alike,” I said as we sat in the conference room down the hall from his office in Building One on the Dell Computer campus in Round Rock. “We’re about the same age. We’re both nice Jewish boys from big cities. We both sold newspaper subscriptions. My daughter goes to the school your kids went to. But you’re worth billions, and I’m not. Why? Why you and not me?”

For a moment Dell looked at me as if I were crazy, then realized I was kidding. He smiled as broadly as he would in our time together and returned the volley. “Why not you?” he said. “It’s not my fault that other people aren’t successful. I wish you all the success in the world.”

Touché. He gave as good as he got. Better than good, actually: His half-serious answer was more revealing than the totally serious one that followed (“I think I’ve been resourceful…I’ve been opportunistic…I’ve identified discontinuities in the marketplace . . .”). Entrepreneurship is the art of the possible. Anyone with money and a good idea—the fabled dollar and a dream—has what it takes to write his own ticket; why not me indeed? The hitch, of course, is follow-through. You have to execute. You have to do it. And no one in the history of Texas business has done it as well as Michael Dell.

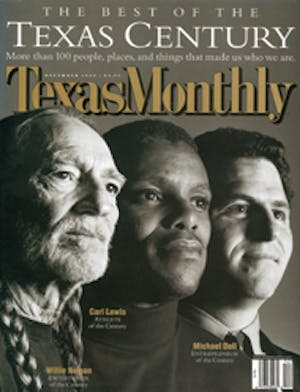

His accomplishments stack up like the planes sometimes do on the runway at the new Austin Bergstrom International Airport (which was made necessary, it can be reasonably argued, by the economic boom that Dell Computer helped ignite in Central Texas). Number one in the U.S. in personal computer sales. Number two in the world. More than $21 billion in sales over the past four quarters, including an average of $30 million a day on the Web. The best-performing stock of all time. Dell himself is the youngest CEO of a company ever to land on the Fortune 500 and the longest-tenured chief executive in the computer industry. He’s the richest Texan of all time—far richer, say, than H. Ross Perot ever was. He’s also the fifth-richest person in America, according to Forbes, and the richest under 40, according to Fortune. About the only thing he isn’t is the richest man in America, period—that honor belongs to his friend Bill Gates—but he’s not even 35 yet; what’s the hurry?

BY NOW THE DELL LOG-CABIN STORY IS THE STUFF OF LEGEND. He was raised in an upper-middle-class neighborhood of west Houston, by his mother, a stockbroker, and his father, an orthodontist. Precocious at age eight, he clipped a form from the back of a magazine and applied for a high school equivalency diploma. At nine, he got his own checkbook. At twelve, he ran a mail-order stamp-trading business, earning $2,000. At fifteen, he bought his first computer, an Apple II, and promptly took it apart to see how it worked. At sixteen, he began selling subscriptions to the Houston Post, pocketing $18,000 in commissions in a twelve-month stretch (yes, you read that right). At eighteen, he enrolled at the University of Texas at Austin and started selling upgraded PCs out of his dorm room high above Dobie Mall (the current residents of that room have a Compaq computer, plus a pinup of Leonardo DiCaprio and a poster declaring “Shit happens”—not a bad business philosophy, by the way). A few months later he moved into an off-campus condo and registered his business; at the end of his freshman year, he quit school altogether.

The rest is history—and, to an extent, mystery, because many of the accounts of Dell’s rapid rise take at face value that he’s done something unfathomable without addressing the simple question of how, exactly, he got from there to here. The answer is equally simple: He did three things.

He built a company. From the beginning, Dell articulated a vision for his fledgling business, and he rarely wavered. “The core concept,” he told me, “was that these dealers were popping up all over the countryside who didn’t know much about computers, and they had incredibly high markups. So they created all sorts of opportunities: a better level of service and a lower cost structure, by working directly with the consumer.”

Onto that premise—eliminate the middleman—Dell grafted the idea of a build-to-order model, in which the company would minimize its inventory and maximize its ability to serve its customers by assembling a computer only when someone wanted one. At least as far as the PC industry went, it was a revolutionary rejiggering of the laws of supply and demand; the latter would drive the former, not the reverse. Initially, Dell’s presumed rivals, Compaq and IBM, paid him no mind—one Compaq executive predicted that the kid with the Coke-bottle glasses would be out of business in a few weeks—but both have long since come around; Compaq now embraces build-to-order, and IBM has become Dell’s leading provider of parts. The mountain has come to Muhammad.

Along the way, Dell has shown he can run the company he founded—no easy feat. “Conventional wisdom says that most entrepreneurs are good at starting companies but not good at managing them once they reach a certain size,” says Joan Magretta, a contributing editor at the Harvard Business Review. “Dell can do both.” In particular, he wins points for his precise attention to the details of his business (referred to as “Michaelmanaging”) and for his record of hiring senior executives—for recognizing, in the words of Dallas attorney Tom Luce, a Dell director since 1990, that “a $500 million company and a $25 billion company require people with different skill sets.”

Dell is also routinely praised for graciously accepting criticism, a sign of maturity well beyond his years. “His willingness to listen is unbelievable,” says Tom Green, the company’s senior vice president for law and administration. “He detects insight, mines it, absorbs it all, and acts on it immediately.” Luce, who has two children older than Dell, remembers flying to Austin to meet him: “Frankly, I was thinking, ‘This is gonna be a twenty-five-year-old who knows everything.’ I was very impressed by how open he was. I later kidded [UT System chancellor] Bill Cunningham that there must not be much value to a UT education.”

He created wealth. “I’m a firm believer that success that’s shared is always better,” Dell said. All over the world, there are people who would agree. Dell stock has increased in value by 69,000 percent in the last decade—yes, you read that right too—expanding the ranks of the rich to include both investors who bought into the company early and employees at all levels who receive stock options.

There’s no way to measure the number of so-called Dellionaires in Texas or anywhere else, but the anecdotal evidence of their existence is startling. In certain circles in Austin, for instance, everyone is talking about the lawyer who recently sold his house for twice its appraised value to a techie who’d just moved to town. How, the lawyer asked, could the buyer afford it? He had invested a modest sum in Dell when the stock went public and was now a millionaire many times over. For every story like that one, there are two or three that are more earthbound, involving people who sold Dell stock to make a down payment on a house or pay for college for their kids. (And there are sob stories: A guy in my poker game reports that he bought five hundred shares of Dell stock at $4 and sold them at $8.)

Dell the man has gotten rich too. Forbes puts his net worth at $20 billion—Fortune says it’s $21.49 billion; what’s $1.49 billion between friends?—and he and his wife, Susan, live with their four children in a 33,000-square-foot mansion west of Austin. As is often the case with enormous wealth, however, Dell’s has invited intense scrutiny. When his house was being built, for instance, Dell came under fire for challenging a Travis County tax assessor’s valuation as unfair; his critics charged that he was trying to weasel out of paying the appropriate level of property taxes (he and the county eventually reached a settlement).

And there are those in the press—among them, columnists for Vanity Fair, Fortune, and Texas Monthly Biz—who’ve wondered aloud whether Dell is overpaid, his stock’s steady climb notwithstanding. From January 31, 1998, to January 31, 1999, counting his salary, bonus, and paper profits from his stock options, his total pay was $1.4 billion, “more than twice the compensation I have ever seen for a single year’s work,” Graef Crystal wrote in Texas Monthly Biz. Such criticism is “nonsense,” Luce says, noting that Dell’s bonus and stock options are incentive pay: “He only makes money if the company makes money.” Dell agrees, offering his own wry take on the issue. “If I were the CEO of Compaq,” he says with a chuckle, “then I would be overpaid.”

He gave back to his community. Only a few years back, Austin’s high-tech entrepreneurs were the subject of a whisper campaign: The money goes up MoPac and I-35, the line went, but it doesn’t come back down. That is, Michael Dell and others like him were quick to take tax breaks to locate their companies in the Silicon Hills north of the city, but they were slow to say thanks by donating to downtown arts organizations and other non-profits when the money started rolling in.

Better late than never. Nowadays, Dell is unrivaled as a role model for good works. In the past five years he and his wife have donated forty acres to the Jewish Federation of Austin for the creation of a Jewish community center, $7 million to the Austin Museum of Art, $3 million to Saint Andrew’s Episcopal School, $1 million to the Austin Children’s Museum, $1 million to the Children’s Hospital of Austin, and $500,000 to the Austin Public Library. And they’re not the only ones: The Dellionaires have given way to the Dellanthropists. The two-year-old Dell Foundation doled out more than $400,000 in 1998, while other cash-rich Dell executives have been giving as well. When the Dells made their pledge to the art museum, four of his top lieutenants and their wives kicked in $6 million more.

DELL MAY BE GENEROUS WITH HIS MONEY, but he’s stingy with information about his home life. The press has rarely been able to penetrate the protective layer that shields the private man from the public view, and that’s how he wants it. Ask even a remotely personal question and he shifts in his seat, politely declining to answer. Ask to interview his family and the request is turned away—again, politely. Ask any of his colleagues to describe what their boss is like offstage, and they offer singsong generalities about how he’s so devoted to Susan and the kids, how he used to work long hours but now tries to make it home for dinner.

A balance between family and work? It’s another thing about Dell’s life that we’d all like to emulate, and he would no doubt wish us all the success in the world.