Getting up at four-thirty in the morning is no big thing if you do it to keep a date with destiny. Like a six o’clock tee time at Willie Nelson’s Pedernales ranch to film a small but pivotal role in the farewell episode of Walker, Texas Ranger. On May 19 Chuck Norris’ all-American, small-screen masterwork signed off after eight years, the second-longest run ever for a CBS Saturday night show, behind only Gunsmoke. The historic finale was a two-hour special with a parallel Walker story line set in the Old West, and I, after weeks of negotiations with the show’s publicist and casting director, was to be killed.

First I sat through an intense half-hour in makeup with a gypsy-mystic named Nono who tried to “take some of the sweetness out of that face.” But four hours later, after spinning my wheels as a “frightened townsperson walking across the street” and then as a “frightened townsperson standing by the saloon,” I grew leery. After lunch, I looked to Leo, the refusenik assistant director. But he was banging his shoe at Fernando, the Spanish director of photography, who was griping that he couldn’t hear over the chatter of the career Old West reenactors, who were grousing that the wardrobe lady wouldn’t let them wear their “period correct” bandoliers, none of which had anything to do with me or my immortality. After the third visit from the makeup girls, who brought more charcoal to dirty my neck and brown nail polish to yellow my teeth, I started to think I was being put on. By the time I heard that Aaron Norris, the star’s younger brother and director of the show, was taking too much time playing Peckinpah with the gunfight scene, I knew the score.

I walked off sullenly to the far end of town where some goats were tied to a water tower. There was a small man there dressed like a Western dandy. I recognized him. “Hey, you’re Larry from Newhart, aren’t you?” As in, “And this is my other brother, Darryl.”

“Hi, I’m Bill,” said William Sanderson. “I play the mayor on the last two episodes.”

“Do you get killed?”

“No,” he smiled, “but that was the first thing I looked for when I got the script.” I nodded like I understood, and he walked away.

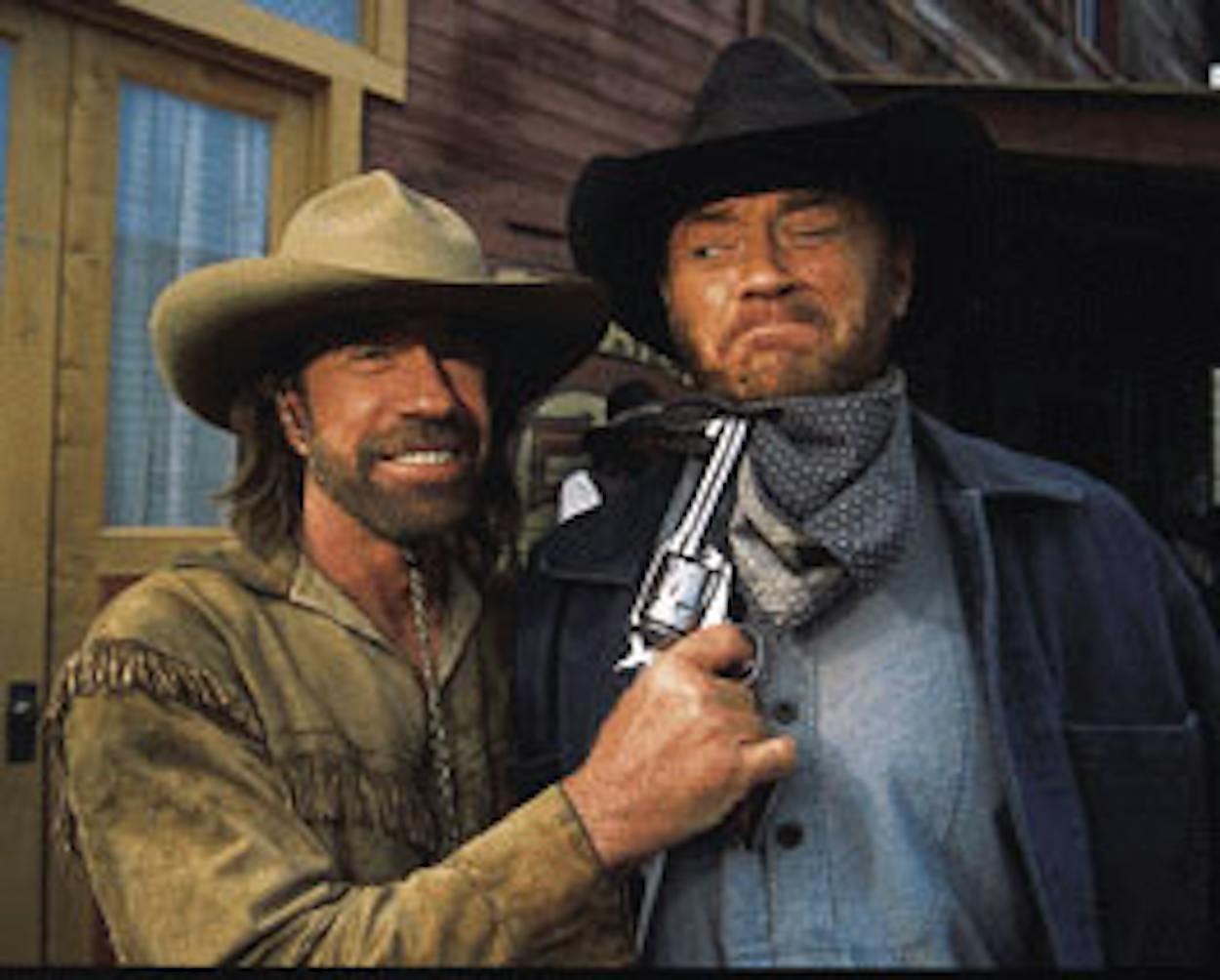

I stewed until about six o’clock, when I was awarded a sympathy photo op with “Mr. Norris,” as I’d been instructed to call him. As we stood there smiling for the photographer, the shutter’s click like the flap of fame’s wings as she flew off into the gloaming, I reached my limit. “Hey, Chuck, how about a shot with a little more action in it? Why don’t you try to kick my hat off my head?”

“What?” he asked, as the two hundred or so cast and crew members—along with their spouses, kids, and pets, all on hand to watch the final shoot—gasped.

“I said, ‘Hey, Chuck, why don’t you kick my hat off my head?'”

“That wouldn’t be Western.”

Then he grabbed me by the back of the neck, more or less playfully, and put his six-shooter under my chin. “How’s this?”

Click. Immortality. Of a sort.

But then he threw a real curve. Instead of storming off, he sat down and asked what I wanted to know. He told me how proud he was of his show, its long run and strong values: “Walker proved that traditional, apple pie-type shows can work.

“You know why that is?” he asked. “It’s because the friends I have here, in my crew and the actors, they are real friends. When it gets down to the nut cracking, that’s really what it’s all about.” He bragged about being able to get actors like Sanderson for his last show and talked about all of the kids from the Make-A-Wish Foundation he had shown around the set. Then, on one of the benchmark days of his life, he returned to work—not just to kill the outlaws but also to kiss the babies, pet the puppies, and take the pictures with the crew.

And that fickle dame destiny? She blew off our date to ride away with the Ranger, and I guess I understand why.