It’s perhaps the most commonly trod path to immortality in contemporary Hollywood: Labor for a few years on television or in B pictures until people realize that your talent far outclasses its surroundings. Score a big break with a major director, earn rave reviews, commence the stockpiling of Oscar nominations, and just keep getting bigger and better. It worked for Tom Hanks (remember his salad days of He Knows You’re Alone and Bosom Buddies) and Denzel Washington (recall Carbon Copy and St. Elsewhere).

And, at least until 2005 or so, it seemed to be working for Jamie Foxx. Early in his career, the Terrell-born actor, whose given name is Eric Marlon Bishop, combined breakneck comic timing and appealing self-awareness to resist the minstrelsy impulses of both the sketch comedy series In Living Color and the sitcom The Jamie Foxx Show. Tapped by Oliver Stone to play a cocksure quarterback in the football drama Any Given Sunday (1999), Foxx, who was a quarterback at Terrell High School, displayed considerable sex appeal: bedroom eyes, a killer sideways grin, a muscular physique he wasn’t shy about showing off. Then everything came together for him, thrillingly, in 2004. He was tender and quietly haunted as a head-in-the-clouds taxi driver co-opted by an assassin (Tom Cruise) in Michael Mann’s Collateral and physically transformed as Ray Charles in Taylor Hackford’s Ray. He earned Oscar nominations for both, winning the Best Actor prize for the latter—at which point we all waited to see what he would do next. Might Foxx take a page from Hanks, who so movingly stripped away all traces of Hollywood vanity in Saving Private Ryan and Cast Away? Would he attempt to do what Washington did in Training Day and Man on Fire and use his gravitas to transform trashy genre material into contemporary classics?

As it turned out, Foxx apparently didn’t have a next step planned. He continued to act regularly in movies, among them the musical Dreamgirls (2006), the action thriller The Kingdom (2007), and the star-studded rom-com Valentine’s Day (2010). He also launched his own satellite radio channel, released three albums of respectable R&B, and won a Grammy for his collaboration with Kanye West on “Gold Digger.” But nothing he’s done on-screen since Ray and Collateral has even hinted at his extraordinarily supple range or his knack for showing us how a man’s bighearted dreams can easily slide into pathetic self-delusion. (Let’s not forget his much-too-brief turn as Drew “Bundini” Brown opposite Will Smith’s Muhammad Ali in 2001’s Ali.) Reading about his frequent appearances on the Los Angeles–Las Vegas–Miami Beach party circuit—or listening to his 2009 rant on his radio show against Miley Cyrus, urging her to “make a sex tape and grow up”—you can’t help but wonder if he’s become more enamored of his own celebrity than the work that made him famous.

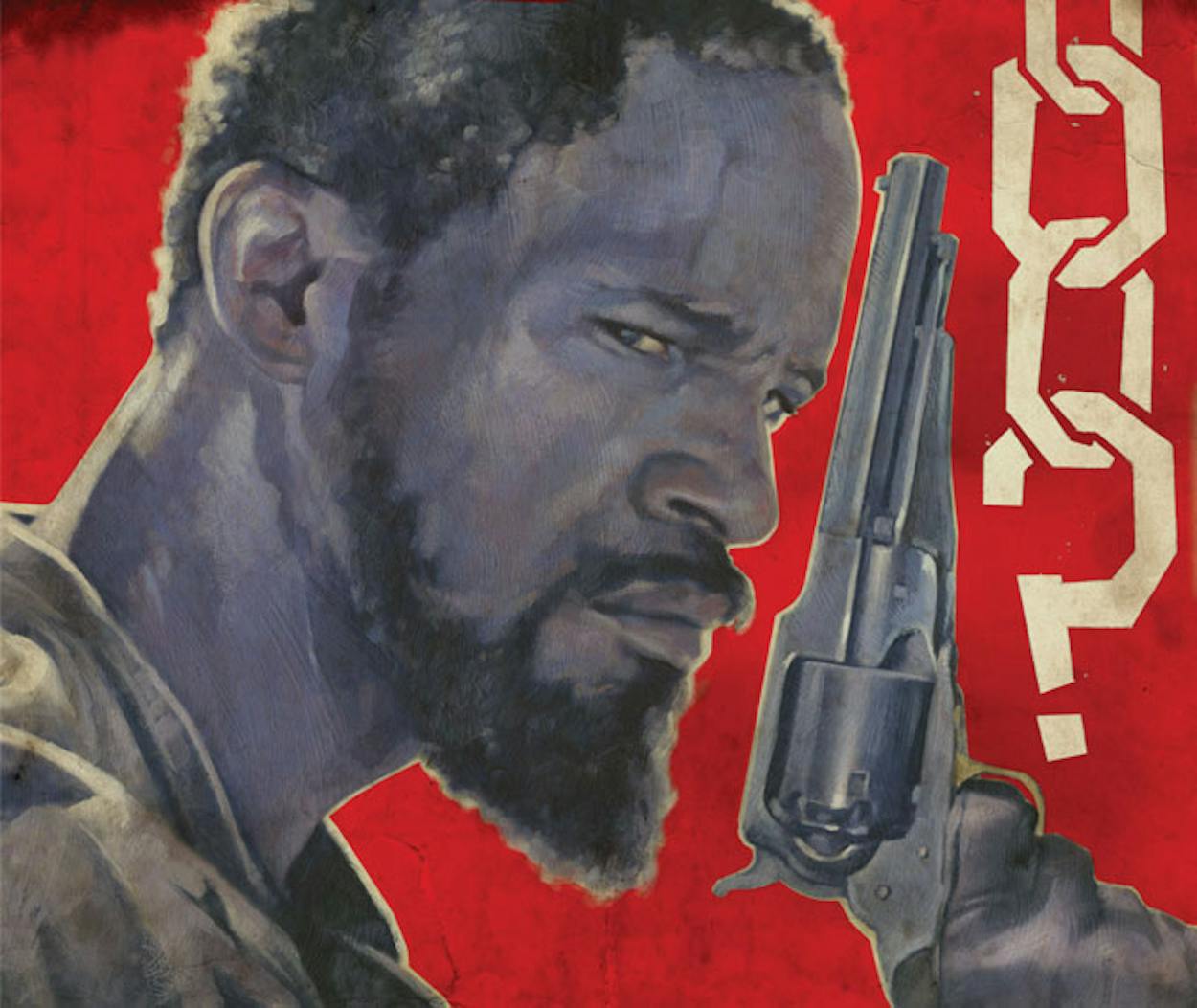

On Christmas Day, Foxx, now 45, returns in Quentin Tarantino’s neo-blaxploitation thriller Django Unchained—his first lead role since 2009’s dreadful Law Abiding Citizen. As of early December, the film wasn’t yet ready to be screened for the press. But no matter how Foxx is in the film, the arrival of Django Unchained raises some tough questions: What went so awry for Foxx that we now have to talk about him in terms of a comeback, a mere eight years after he seemed to be on top of the world? Is the actor to blame for a series of missed opportunities? Or was he crushed by an unforgiving system that offers little margin of error for performers of color?

One of the ironies of Foxx’s career is that his recent stumblings seem bound up in his greatest triumph. With a cryptic smile and an upturned head constantly in motion, as if listening to a celestial sound track that only he could hear, Foxx completely lost himself inside the role of Ray Charles. More than a dazzling impersonation, though, his acting also revealed layers of sensuality, frailty, deviousness, and competitiveness—it’s one of the most believably human biopic performances ever wrought.

Yet Foxx spent so much time promoting Ray and then walking red carpets and collecting prizes for it that he became completely identified with the role; a proper follow-up was rendered all but impossible. He was wise to take on supporting roles in prestige projects like the war drama Jarhead (2005) and the Broadway adaptation Dreamgirls. But both movies were muddled, and instead of stealing the show as he once commonly did, Foxx just faded into the woodwork. He followed those films with a series of lousy choices and flat-out terrible performances. He muttered his way through Mann’s incoherent update of Miami Vice (2006). He spread the Velveeta on extra thick as a homeless cello prodigy in Joe Wright’s laughably pretentious The Soloist (2009). He trotted out the same hoary ghetto badass routine in blink-and-you’ll-miss-him cameos in Due Date (2010) and Horrible Bosses (2011).

Maybe Foxx, after years of clawing his way to glory, grew weary of the Hollywood game—hence his renewed focus on a music career. (Indeed, he looks looser and more playful in the 2009 video for his hit single “Blame It (On the Alcohol)” than he does in any of his recent movies.) Equally plausible is that race has been a factor: whereas Hollywood tends to view box office disappointments like Larry Crowne and Cloud Atlas as mere road bumps for someone like Hanks, back-to-back flops like Miami Vice and The Kingdom are seen as evidence that Foxx doesn’t have what it takes to be a leading man.

And so, whether Foxx wasn’t offered them or didn’t aggressively chase after them, the roles that might have pushed him to even greater heights haven’t been forthcoming. You can’t help but wonder what Foxx might have done with George Clooney’s role in The Ides of March or Daniel Day-Lewis’s in Nine, playing men whose decency and caddishness are inextricable, or how much more intriguing the recently rebooted Bourne franchise might have been with Foxx’s lithe physicality and fleet sense of humor in place of the starchy, thick-muscled solemnity of Jeremy Renner.

At least on paper, Django Unchained sounds like a tremendous opportunity—a quintessential Tarantino mash-up of multiple genres and visual styles. Foxx plays the title character, a pre–Civil War slave working with a German bounty hunter (Christoph Waltz) who promises him his freedom if he can help capture three elusive killers. Certainly Foxx couldn’t have asked for a better director; from John Travolta in Pulp Fiction to Robert Forster and Pam Grier in Jackie Brown, Tarantino has proved expert at relaunching fallen stars into their proper orbit.

Yet there’s a nagging footnote to this attempted comeback: Foxx was cast in Django Unchained only after Tarantino very publicly pursued Will Smith for the part and was turned down. It’s an unavoidable reminder of Foxx’s tenuous status in Hollywood, where he’s still stuck playing second fiddle to Smith. If the film underperforms commercially, expect Foxx to receive a disproportionate share of the blame (it needed a bankable star like Brad Pitt in Inglourious Basterds, the pundits will argue). What aches most about this is that there are so many challenging roles for Foxx to tackle as he enters his late forties: a scenery-chewing Bond villain on the order of Javier Bardem in Skyfall, a magnetic and terrifying antihero à la Denzel Washington in American Gangster. But they won’t come his way until Foxx remembers to pay his talent the respect it deserves—and reminds Hollywood to do likewise.