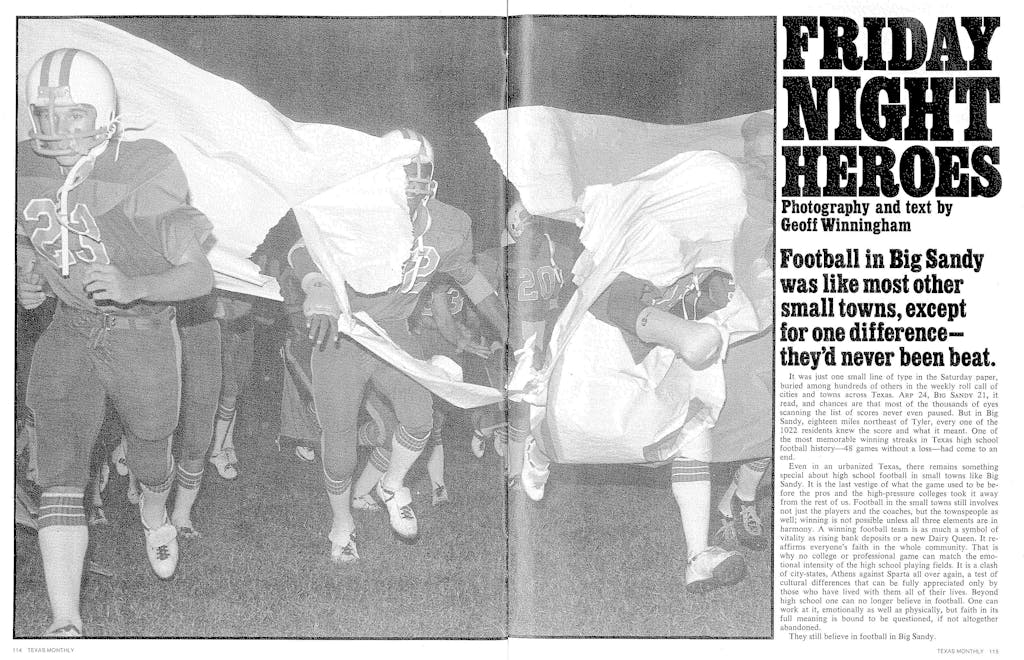

It was just one small line of type in the Saturday paper, buried among hundreds of others in the weekly roil call of cities and towns across Texas. Arp 24, Big Sandy 21, it read, and chances are that most of the thousands of eyes scanning the list of scores never even paused. But in Big Sandy, eighteen miles northeast of Tyler, every one of the 1022 residents knew the score and what it meant. One of the most memorable winning streaks in Texas high school football history—48 games without a loss—had come to an end.

Even in an urbanized Texas, there remains something special about high school football in small towns like Big Sandy. It is the last vestige of what the game used to be before the pros and the high-pressure colleges took it away from the rest of us. Football in the small towns still involves not just the players and the coaches, but the townspeople as well; winning is not possible unless all three elements are in harmony. A winning football team is as much a symbol of vitality as rising bank deposits or a new Dairy Queen. It reaffirms everyone’s faith in the whole community. That is why no college or professional game can match the emotional intensity of the high school playing fields. It is a clash of city-states, Athens against Sparta all over again, a test of cultural differences that can be fully appreciated only by those who have lived with them all of their lives. Beyond high school one can no longer believe in football. One can work at it, emotionally as well as physically, but faith in its full meaning is bound to be questioned, if not altogether abandoned.

They still believe in football in Big Sandy.

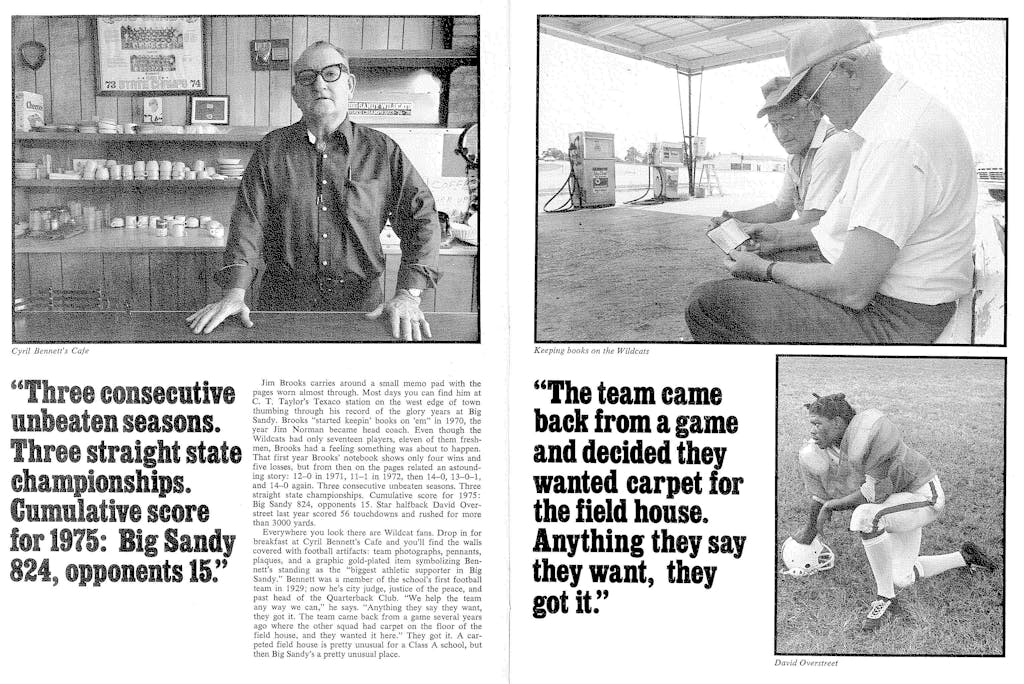

Jim Brooks carries around a small memo pad with the pages worn almost through. Most days you can find him at C. T. Taylor’s Texaco station on the west edge of town thumbing through his record of the glory years at Big Sandy. Brooks “started keepin’ books on ’em” in 1970, the year Jim Norman became head coach. Even though the Wildcats had only seventeen players, eleven of them freshmen, Brooks had a feeling something was about to happen. That first year Brooks’ notebook shows only four wins and five losses, but from then on the pages related an astounding story: 12-0 in 1971, 11-1 in 1972, then 14-0, 13-0-1, and 14-0 again. Three consecutive unbeaten seasons. Three straight state championships. Cumulative score for 1975: Big Sandy 824, opponents 15. Star halfback David Overstreet last year scored 56 touchdowns and rushed for more than 3000 yards.

Everywhere you look there are Wildcat fans. Drop in for breakfast at Cyril Bennett’s Cafe and you’ll find the walls covered with football artifacts: team photographs, pennants, plaques, and a graphic gold-plated item symbolizing Bennett’s standing as the “biggest athletic supporter in Big Sandy.” Bennett was a member of the school’s first football team in 1929; now he’s city judge, justice of the peace, and past head of the Quarterback Club. “We help the team any way we can,” he says. “Anything they say they want, they got it. The team came back from a game several years ago where the other squad had carpet on the floor of the field house, and they wanted it here.” They got it. A carpeted field house is pretty unusual for a Class A school, but then Big Sandy’s a pretty unusual place.

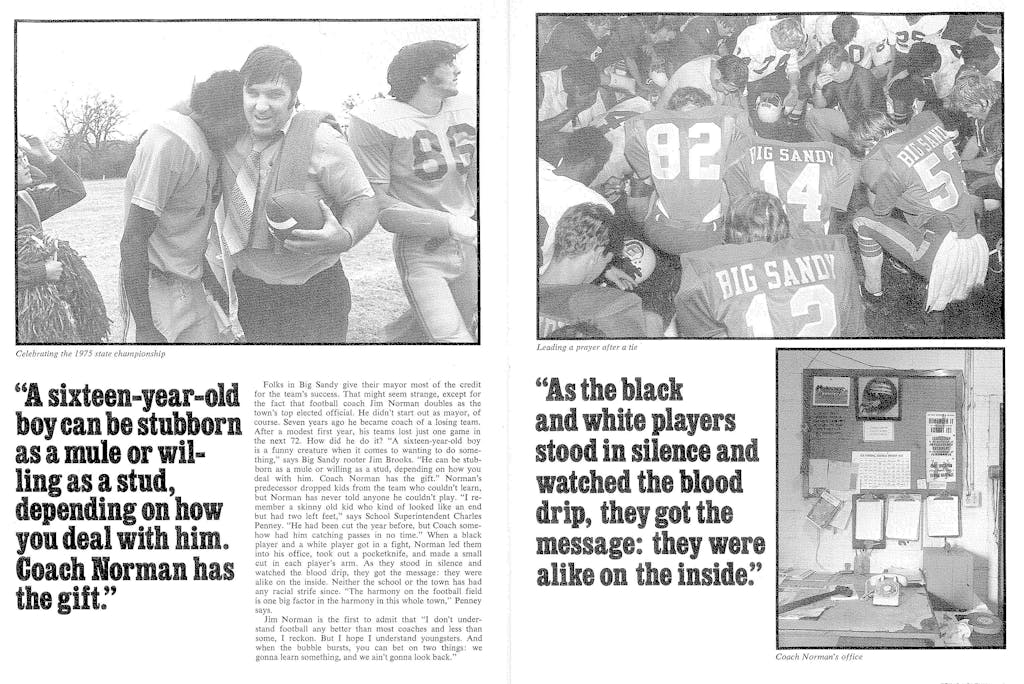

Folks in Big Sandy give their mayor most of the credit for the team’s success. That might seem strange, except for the fact that football coach Jim Norman doubles as the town’s top elected official. He didn’t start out as mayor, of course. Seven years ago he became coach of a losing team. After a modest first year, his teams lost just one game in the next 72. How did he do it? “A sixteen-year-old boy is a funny creature when it comes to wanting to do something,” says Big Sandy rooter Jim Brooks. “He can be stubborn as a mule or willing as a stud, depending on how you deal with him. Coach Norman has the gift.” Norman’s predecessor dropped kids from the team who couldn’t learn, but Norman has never told anyone he couldn’t play. “I remember a skinny old kid who kind of looked like an end but had two left feet,” says School Superintendent Charles Penney. “He had been cut the year before, but Coach somehow had him catching passes in no time.” When a black player and a white player got in a fight, Norman led them into his office, took out a pocketknife, and made a small cut in each player’s arm. As they stood in silence and watched the blood drip, they got the message: they were alike on the inside. Neither the school or the town has had any racial strife since. “The harmony on the football field is one big factor in the harmony in this whole town,” Penney says.

Jim Norman is the first to admit that “I don’t understand football any better than most coaches and less than some, I reckon. But I hope I understand youngsters. And when the bubble bursts, you can bet on two things: we gonna learn something, and we ain’t gonna look back.”

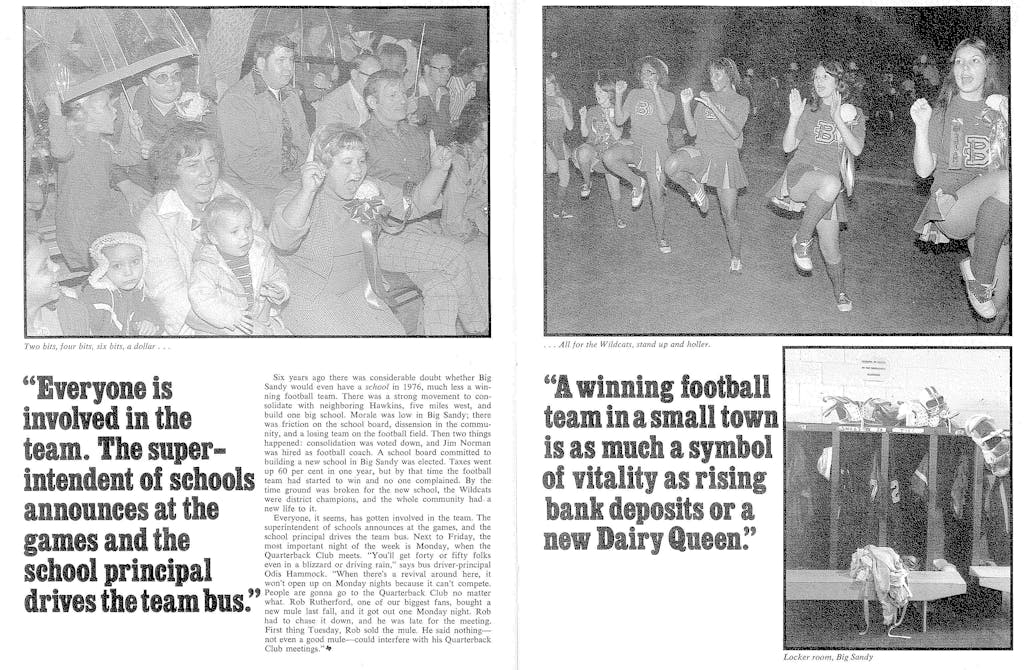

Six years ago there was considerable doubt whether Big Sandy would even have a school in 1976, much less a winning football team. There was a strong movement to consolidate with neighboring Hawkins, five miles west, and build one big school. Morale was low in Big Sandy; there was friction on the school board, dissension in the community, and a losing team on the football field. Then two things happened: consolidation was voted down, and Jim Norman was hired as football coach. A school board committed to building a new school in Big Sandy was elected. Taxes went up 60 per cent in one year, but by that time the football team had started to win and no one complained. By the time ground was broken for the new school, the Wildcats were district champions, and the whole community had a new life to it.

Everyone, it seems, has gotten involved in the team. The superintendent of schools announces at the games, and the school principal drives the team bus. Next to Friday, the most important night of the week is Monday, when the Quarterback Club meets. “You’ll get forty or fifty folks even in a blizzard or driving rain,” says bus driver-principal Odis Hammock. “When there’s a revival around here, it won’t open up on Monday nights because it can’t compete. People are gonna go to the Quarterback Club no matter what. Rob Rutherford, one of our biggest fans, bought a new mule last fall, and it got out one Monday night. Rob had to chase it down, and he was late for the meeting. First thing Tuesday, Rob sold the mule. He said nothing—not even a good mule—could interfere with his Quarterback Club meetings.”

- More About:

- Sports

- Photo Essay

- High School Football