The first theater in Houston to show Deep Throat was also the first theater to show the currently revived King of Hearts as well as Antonioni’s Red Desert, Truffaut’s The Soft Skin, Godard’s Vivre Sa Vie, and many other films from the finest European directors. The Alray, in spite of this illustrious past, has been showing films like Deep Throat for almost five years. Ray Boriski, the Alray’s manager since 1959, is not especially happy about the changes in times, tastes, and economics that forced him to transform his theater. On the other hand, he’s not especially sad about them either.

The first theater in Houston to show Deep Throat was also the first theater to show the currently revived King of Hearts as well as Antonioni’s Red Desert, Truffaut’s The Soft Skin, Godard’s Vivre Sa Vie, and many other films from the finest European directors. The Alray, in spite of this illustrious past, has been showing films like Deep Throat for almost five years. Ray Boriski, the Alray’s manager since 1959, is not especially happy about the changes in times, tastes, and economics that forced him to transform his theater. On the other hand, he’s not especially sad about them either.

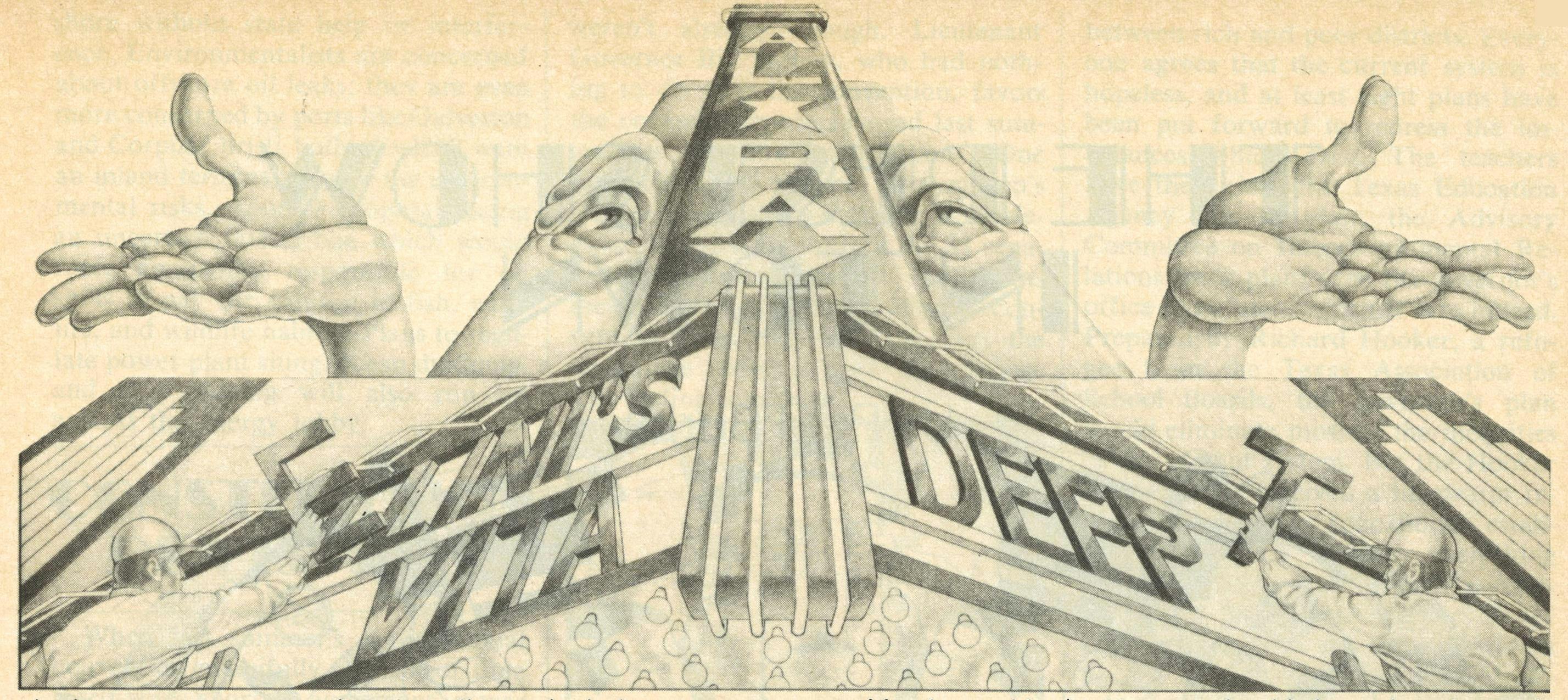

The Alray is on Fulton Street, an obscure thoroughfare in a disintegrating part of north Houston. It was originally the Lindale theater and was built in 1940, long before the age of freeways, when neighborhood theaters were exactly that, places where local families could go on foot for an evening’s entertainment. But when Ray became interested in the theater in 1959, the neighborhood theater business was declining, at least in Houston, and the Alray stood empty. It had last been used as headquarters for something called the Southern Baptist Pentacostal Institute.

Boriski and a partner leased the theater for $50 a month and named it by combining their two first names. With the theater came a pair of 35-millimeter projectors which worked more or less on whim. Boriski couldn’t afford to replace them until years later. He bought 700 theater seats from the old Hippodrome Theater in Dallas; his father, who through the years was a jack-of-all trades at the Alray, installed them and kept them in repair. Boriski bought the screen for $25 from the old Isis in Houston, repainted it himself, patched the holes, and still uses it today.

Boriski and his partner leased the theater intending to show family films. They hoped to draw their clientele from the surrounding area, a neighborhood far enough from downtown Houston to seem in need of a nearby theater. But the days of the family theater really were over, even by 1959. They showed a series of innocuous Hollywood movies and no one came. In an attempt to recoup their losses, Ray showed a film that in 1959 was as notorious as Deep Throat is today, Russ Meyer’s The Immoral Mr. Teas. The film had been featured in a photo spread in Playboy and it opened at the Alray, to packed houses. The theater even started opening for matinees.

Films like Mr. Teas were known as “nudies.” They were the forerunners of the contemporary pornographic film, although they were very mild by current standards. Their plots and characters existed for the sole purpose of producing situations where a woman could appear nude. Door-to-door salesmen were a favorite motif; their knocks were invariably answered by women who had chosen to do the most amazing things, like bake a cake, in the altogether. The women tended to stand rather still and let the camera play over them, since there was rarely any physical contact or any of what has come to be known as “full frontal nudity.” Russ Meyer, who through the years earned the enviable title of “King of the Nudies,” is now something of a cult figure. He has been honored at film festivals and has been the subject of graduate dissertations. Other directors, who later made reputations in Hollywood, cut their teeth on the nudies, among them Francis Ford Gopolla, who directed The Godfather.

Ray and his partner continued showing nudies for a month or two until the priest of his partner’s parish made a comment about the evil of such films and Ray’s partner decided he didn’t want to be part of the nudie business anymore. They went back to showing family movies and once again, no one came. Then they tried Mexican films which had an equal lack of success. By that time Ray’s partner wanted out of the Alray altogether and Ray began running the theater on his own.

He did not want to go back to showing nudies even though they were the only shows that had been at all successful in his theater. He got no sense of personal satisfaction from showing them. He knew about the Thalia theater in New York which was showing new films from the Italian, French, and Japanese directors who, though still generally unknown in the United States, were beginning to evoke some interest. Ray was interested in those films himself, believed in them in a way he didn’t believe in the Hollywood, movies being made at the time and in a way that he certainly couldn’t believe in nudies. He decided to see if he could make a theater showing foreign films work in Houston. It worked, barely, and for ten years Ray Boriski was able to hang on.

It wasn’t easy. His average gross was only $700 a week and some weeks he didn’t even gross $300. He had one employee, a union projectionist. He did all the rest of the work himself. He took tickets, made the free coffee he gave away in small paper cups, ordered the films, swept up at night, kept his own books, cleaned out the urinals. When he got married, he had to call around to his friends to find someone who would run the theater for him for one night. The next day he was back at work.

In the early Sixties the phrase “French film” was invariably accompanied by a leer. Public awareness of directors like Fellini, Antonioni, Godard, and Truffaut, an awareness which would blossom later in the decade, was only be ginning to sprout, mostly on college campuses. “I had a small core of regulars,” Boriski recalls, “which was just large enough to cover my expenses. But to make any money at all, and I’ve never made much, I had to attract some people, just a few people, outside that core.”

On the other hand, this limited demand meant that the films he showed could be rented from distributors for very little money. The film that consistently drew the largest crowds at the Alray was Black Orpheus. “I could rent it for $25 for three days of showings,” Boriski explained later. “I brought it back seventeen or eighteen times and it always helped me when things started getting tight. To rent that film today I’d have to put up a $500 guarantee which I’d have to pay whether anyone came to see it or not.”

The Alray’s audience was mostly Saint Thomas and Rice students seasoned with a heavy sprinkling of people from various walks of life who for one reason or another were interested in film. This dedicated core over the years came to recognize each other and tended to take a personal interest in the running of the theater. “They would stay after the show was over,” Boriski says, “and suggest films or give me ideas on how to run the place better.” This feeling of community was amplified by the long drive out to the theater, by its obscure location, by its tiny and unpretentious building, and by the growing realization on the part, of the patrons that the films they were seeing were something special for that time and place, just as the Alray itself was. And going there had its own memorable idiosyncrasies. One night sometime in 1965 I drove out with three other people to see a revival of Rudolph Valentino in The Eagle. We arrived to find a sheepish Ray Boriski smelling of smoke. Valentino’s love scenes were evidently torrid as ever—the film had caught fire in the projectors. For revenge, Boriski buried the charred film in the middle of the Alray’s parking lot.

But as the decade wore on, the Alray became harder and harder to keep going. For one thing, the directors whose movies Ray Boriski had been showing in his small theater had started getting more general notice in the United States. Their new films were now distributed by major studios and played in the city’s larger theaters. Films like Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point or Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451 were released with national publicity and a price tag to exhibitors that the Alray couldn’t afford. With a larger audience these films could no longer command the kind of cult appeal that had given Boriski his central core of patrons. And the energy seemed to go out of foreign films. By the late Sixties the best contemporary movies were being made by Americans and there just weren’t enough new films from Europe to keep drawing customers back to the Alray.

Still, Boriski thinks he might have been able to hold on even at that if it weren’t for inflation. It not only affected the rental price of films but every other expense in running a theater. Projectionists, for instance, earn over $400 a week today, which would be a fairly healthy chunk from an average $700 a week gross. And he could not raise his prices enough to meet the rise in his costs. “I’ve had a lot of people who had money coming to my theater,” he recalls. “Arty types. Women in suede coats and nice shoes, art gallery people, that kind of thing. And you know something about people like that? They’re stingy. A foreign film in those days was like a fine wine. You’d actually expect to pay a premium for it. But when I raised my price from $1.50 to $1.80 you should have heard people complain. It was like I’d let them down. I was never able to charge enough. Today I charge $4 and nobody says a thing. And they’re paying for junk. Junk.”

By 1969 things had gotten to the point that Ray knew he couldn’t go on with the theater the way he had been. He instituted the policy of showing “beaver” films (sixteen-millimeter loops of women undressing, including that old taboo, “full frontal nudity”) in the afternoon until six o’clock and then starting again at seven with foreign movies. It brought in some money, but really didn’t work very well. “You can’t run a theater with two policies. The heavy breathers weren’t interested in the film buffs and the film buffs thought it was a kind of sacrilege to show nude women on the same screen as their movies.”

Near the end of 1969, Boriski threw in the towel and started showing nothing but “adult films.” His first feature was a film named Man and Wife which he charged $5 to see. In the first hour he grossed more than he had during the entire previous week of foreign films. And the Alray has been a consistent money-maker ever since. Today Boriski maintains an office on Montrose Street, and rarely visits the theater he spent so many years trying to keep alive.

“You want to know what I do with the money?” he asks. “I travel. After spending ten years in that one little place, my wife and I go out to see what the rest of the world is like. I suppose if I had started with adult films five years earlier I’d be so wealthy by now I wouldn’t ever need to work. But that’s all right. I think I did something to make my community a little better back then, tried to give people something they wouldn’t have gotten, and I worked hard doing it. I’m going to relax a little now.”

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Movie Theaters