Growing up in the San Felipe Courts housing projects of Houston’s Fourth Ward, Kenny Rogers used to walk to elementary school through better neighborhoods, admiring what he came to recognize as the mark of success: automatic water sprinklers. In the eighties, in the middle of a run that earned him twelve Billboard-chart-topping albums and 24 number-one hits, Rogers built an eighteen-hole golf course at his home near Athens, Georgia, and covered it in automatic sprinklers. “I’d spend hours sitting on a golf cart admiring them,” Rogers says. “I like to joke I have them inside my house now.”

Last year, Rogers documented what is a true rags-to-riches story in Luck or Something Like It: A Memoir, which was released in paperback last month. And on Tuesday, Rogers released a new album, You Can’t Make Old Friends, which reunites him with Dolly Parton, with whom he had the number-one hit “Islands in the Stream” in 1983.

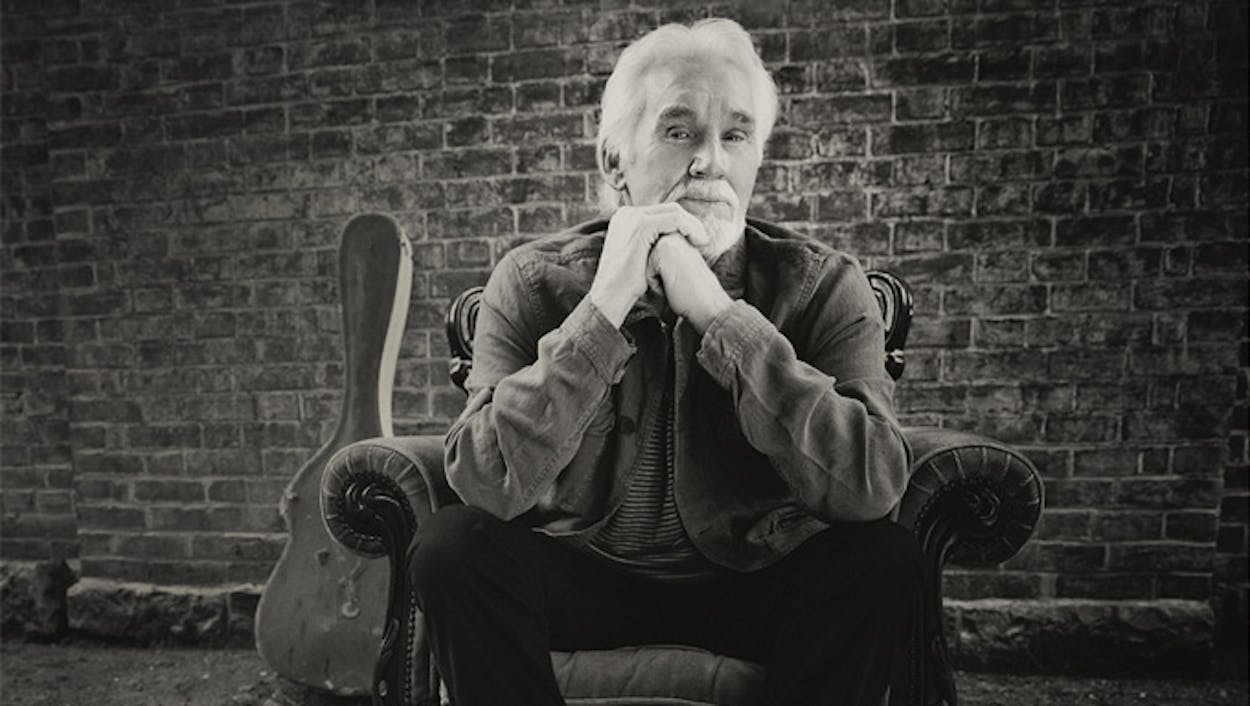

On the eve of his album’s release and his induction this fall into the Country Music Hall of Fame, Rogers, 75, spoke about success, longevity and the key to a great duet.

Andy Langer: Historically, Texans have seemed to approach Nashville and its music business one of three ways: fully embrace it, rebel against it, or try to change it from the inside. You’ve always struck me as a pioneer of that third choice.

Kenny Rogers: Sure, for better or worse. I’m a country singer with a background in jazz and a lot of other influences. Ray Charles was my hero. I’ve always believed country is the white man’s rhythm-and-blues. It’s where the pain is. Right or wrong, I hit Nashville and did some pop songs. I worked with Lionel Richie and Barry Gibb. But I feel like I drew a lot of people to country music who wouldn’t have gone there without me. Country music couldn’t ever understand that not everybody’s history goes back to Hank Williams. For a lot of people, it starts with Alabama or Dolly. And now it starts with Taylor Swift. That’s healthy for country music. I think I took a lot of flak for taking country pop, but I broadened the audience. Country has always been too country for a lot of people.

AL: When you look back at your hits, can you identify a common thread? What makes a song something Kenny Rogers should be singing?

KR: There are two different threads. When I look for a ballad, I look for a song that says what every man would like to say and every woman would like to hear. “Through the Years,” “She Believes in Me,” “You Decorated My Life”—they all fall into that category. What man wouldn’t want to say, “Lady, I’m your knight in shining armor and I love you”? And what woman wouldn’t want to hear that? The other common thread was songs with social commentary. “Reuben James” was about a black man who raised a white child. “Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love to Town” was about a Vietnam vet who came home to a wife having an affair. “Coward of the County”—and I’m amazed how many people don’t know this—was actually about a rape. Even “The Gambler”—it’s about a concept of how to live your life, not necessarily about gambling.

AL: Duets have always been a major part of your success. And on the new record, you’re back with Dolly. What do you know about singing duets that most people don’t?

KR: You don’t start with an artist. You start with a song and say, “Who could sing this well?” And you have to find a song that when it’s done makes a statement. Singing duets is a lot like running a hundred-yard dash. If you go out and run it as fast as you can, that’s one thing. But when you put someone in the lane next to you that runs a little bit faster, you’re going to run faster. That’s what happens with duets. You go in and someone like Dolly really sings and you think, I have to redo my part. And then she redoes her part. And everyone keeps taking it up a notch. That’s what happened here.

AL: As a live draw, is it safe to say the old-school, almost Vegas-like, entertainer aspect of what you do is what has carried you through?

KR: I think that’s what separates me. The thing I tell people when I go out onstage is that it’s not important that one person leave here saying, “He’s the best singer I’ve ever heard.” But it is important that every last person leave saying, “I enjoyed that.” I’ve accomplished a lot of that through laughter. I’ve always found people will clap to be nice, but they won’t laugh to be nice. The easiest route is self-deprecation. People love when you can laugh at yourself.

AL: On the other hand, it can’t hurt that you have a giant bag of hits to draw from.

KR: I’m pretty well armed when I go up there. My theory about hits is that when an audience hears a new song, they have to work very hard to determine subconsciously if they like the song, if they like the way it’s sung and so on. But with a hit, they don’t have to think. They can just smile and clap and sing along. I play new songs occasionally, but I’m much more comfortable doing hits. I went to see Ray Charles once — and I knew him personally by then— and he didn’t do “Georgia on My Mind.” I felt so cheated. That’s what I went to hear. He was tired of doing it. I don’t get tired of hits. I just don’t. I’m grateful for them.