This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

“Madalyn is napping,” my guide told me. “Would you like to take a look?” We weaved through offices filled with visitors from around the country who had come to Austin to attend the dedication of the handsomely appointed new headquarters of the American Atheist Center (valued at $1.7 million) and to mark the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Supreme Court decision that removed prayer and Bible reading from public schools. Madalyn Murray O’Hair, the instigator of that famous lawsuit, was 69 years old and in frail health, and as usual at this hour in the afternoon she was taking a snooze on her couch. Several visitors were peeking through the glass wall into her darkened office. They gave way reluctantly as we approached. There before us lay the first lady of atheism, as she calls herself, in a flower-print dress. “It’s a little like Lenin’s tomb,” my guide observed.

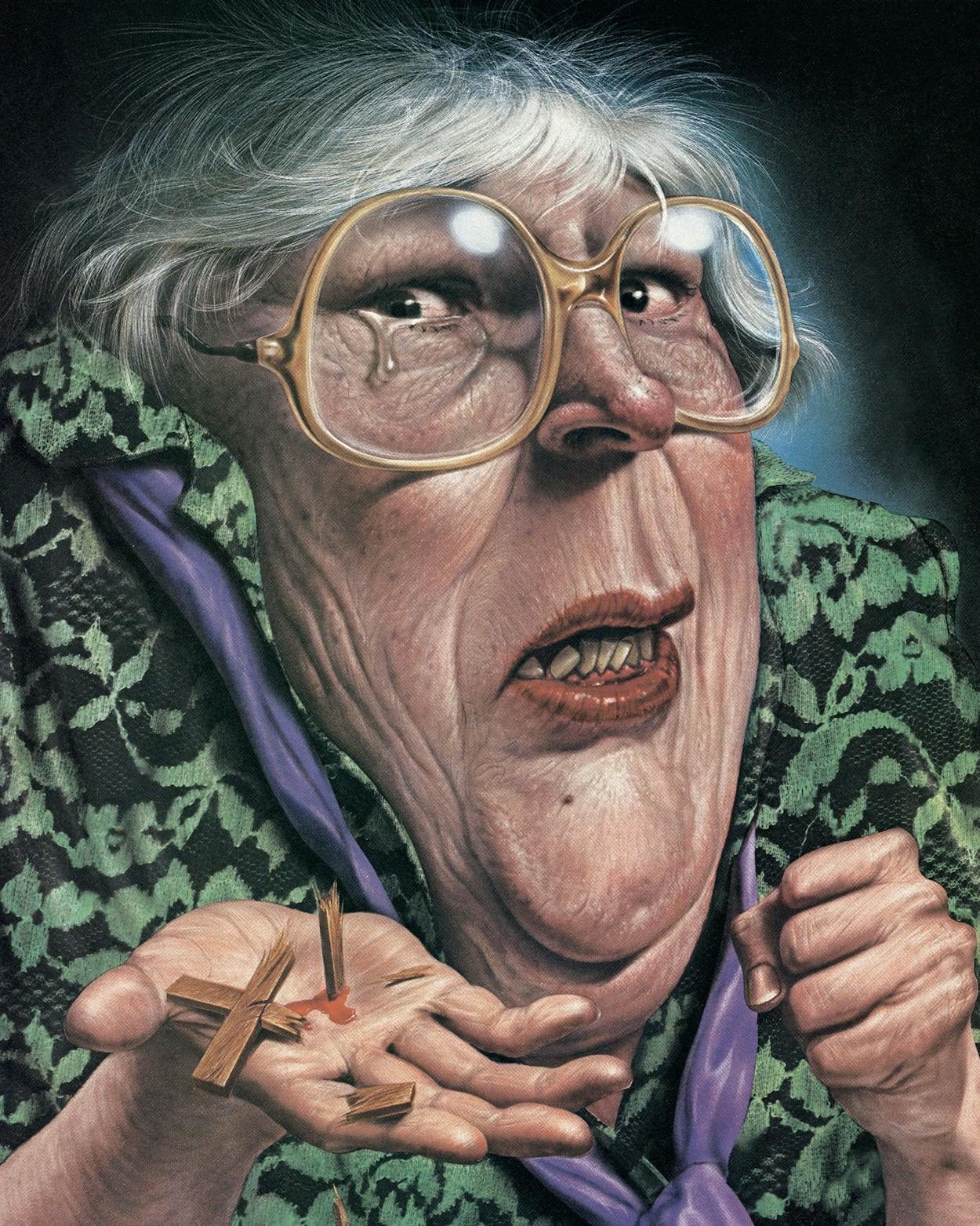

Did she hear us? Suddenly Madalyn startled awake and swung her bare feet to the floor. She ran a hand through her vivid, abruptly cropped white hair. A heavy woman, she appeared even in this half-awakened state like a bowling ball looking for new pins to scatter. Before I could gracefully escape, Madalyn turned to look at the shadow in her office glass, and I was caught by her stare. There was no surprise in her face, only resignation and a look I would see several times again in those brief, unguarded moments when Madalyn stepped out of the spotlight and her mask of anger dropped aside to reveal the anxiety, the fear underneath.

I slipped away in embarrassment, realizing I had started badly with her. As with most Americans my age, my life already had been given a good shaking by Madalyn Murray O’Hair. For the first ten years of my schooling, I listened to prayers and Scripture every morning following the announcements on the P.A. system. I don’t recall ever questioning the propriety of such action or wondering what my Jewish classmates, for instance, might think about hearing Christian prayers in public school. But in the fateful fall of 1963 we began classes amid the enormous hubbub that followed the Supreme Court decision. The absence of morning prayers was widely seen as a prelude to the fall of the West. And the woman who had toppled civilization as we knew it was some loudmouthed Baltimore housewife—that was my impression—who then proceeded to wage another legal campaign to tax church property. She was the first person I had ever heard called a heretic. She jumped out of the front pages with one outrageous statement after another; indeed, the era of dissent in the sixties really began with Madalyn Murray, who styled herself as the “most hated woman in America.”

Certainly she was the most provocative. Soon after the school-prayer decision, Mrs. Murray, as she called herself then, was charged with assaulting 10 Baltimore policemen (she has inflated the number of policemen to 14, then 22, and then 26). She fled first to Hawaii, where she took refuge in a Unitarian church. Then she went to Mexico, which summarily deported her to Texas in 1965. Her odyssey ended in Austin, where she successfully fought extradition to Maryland, married an ex–FBI informer named Richard O’Hair, and remained long after the Maryland charges were dropped.

Over the years I followed Madalyn O’Hair in the way one keeps tabs on celebrities, as she bantered with Johnny Carson, sued the pope, or burst into a church and turned over bingo tables. When I was in college, she came to speak. By then she had achieved a kind of sainthood status with the undergraduate intelligentsia. True to her billing, she raked over capitalism and Christianity and especially Catholicism, unsettling if not actually insulting every person in the auditorium. Afterward she repaired to the student center and held forth in the lobby, giving an explicit and highly titillating seminar on the variations of sexual intercourse. I had never seen anyone with such a breathtaking willingness to endure public hatred. “I love a good fight,” she boasted to the press. “I guess fighting God and God’s spokesmen is sort of the ultimate, isn’t it?”

“I love a good fight. And I guess fighting God and God’s spokesmen is the ultimate.”

Neutrality is never present around Madalyn O’Hair; she polarizes everyone. “The insults she stood, the beatings she suffered paved the way for more modern atheists,” says her friend Frank Zindler. “She has done the consciousness raising. It is accepted now that atheists have the right to exist in America, whereas when she started that was not a given.” Charles Dews, who used to work for her, says, “She’s really a freedom lover. Beneath everything else, Madalyn Murray O’Hair is about freedom.” On the other hand, G. Richard Bozarth, another former employee, calls her a “petty, jealous little ex-bureaucrat who once shouted loud enough to gain attention and has continued shouting for lack of imagination to do anything else—and because it pays.” Her former treasurer, Brian Lynch, says, “I really think she hates herself, and that hatred is projected onto everyone else she comes into contact with.” Everyone has an opinion about Madalyn Murray O’Hair, yet no one who knows her well claims to understand her.

Hungry all her life for money and power, she lives at last in a world of material comfort, surrounded by luxurious German cars and expensive artwork, yet the organization that she created to carry on her crusade is little more than a hollow shell, a sounding chamber for the roar of Madalyn’s complaints. She has suffered the loss of her husband to cancer and the defection, in 1980, of her eldest son, William, to Christianity. Perhaps those losses might account for the anxiety that one sometimes sees in Madalyn’s eyes. More than once I had heard from some gloating Christian that even Mrs. O’Hair stood quaking at the prospect of death. But the more I learned about her, the more I wondered whether it was not death but life that frightened her—life and the contradictions, the lies, and the deceit that made up the furious existence of Madalyn Murray O’Hair.

Awake and arguing, Madalyn was in the computer typesetting room trading opinions with Arthur Frederick Ide, a former Lutheran minister and former Carmelite monk who is the author of Unzipped: The Popes Bare All, which was published by the American Atheist Press. Madalyn and Ide were talking about the government conspiracy to control the flow of information through the mails. A bony, white-haired visitor from Ohio was creeping forward in an office chair, and he ventured the opinion that it was a goddam shame one couldn’t buy stock in the post office monopoly.

“Oh, but you can,” Madalyn said.

“No!” said the Ohioan, suddenly shooting backward in his chair. “But, Madalyn, it’s a government agency.”

“The hell you say. It’s no more a government agency than General Motors.”

“It says ‘U.S. Postal Service,’” the man insisted, creeping forward again. “It’s like a department —”

“It’s nothing of the sort,” Madalyn replied. “It’s, it’s a . . . ”

“It’s an instrumentality,” said Ide. “An instrumentality is an entity that serves the functions of government but is privately constituted.”

“An instrumentality!” said the flabbergasted Ohioan.

“Just like the gawddam Federal Reserve,” Madalyn observed in an accent that harks back to the broad vowels of Tidewater, Maryland.

“The Federal Reserve!” the Ohioan cried. His chair flew back against the wall.

I walked past the typesetting room, following Robin Murray O’Hair, Madalyn’s granddaughter and adopted daughter, who is the editor of the American Atheist magazine and the president of the 40,000-volume Charles E. Stevens atheist library. Robin is a redhead with many of her grandmother’s features, including freckles and a strong, round jaw. Robin also shares Madalyn’s famous love of animals. At the moment, Robin was being towed along by a black spaniel named Princess, one of six dogs that sometimes share her office. “We have commissioned ten new books,” Robin said as we passed through the art department on our way to the audiovisual room. “The latest is I Bought My First Six-pack When I Was 35, which is about a Mormon who overcame religion.” Robin smiled shyly. On the wall, among the frequent photographs of Madalyn, was a framed letter from Bertrand Russell protesting one of Madalyn’s many arrests. “Mrs. O’Hair has been in jail eleven times,” Robin said. “Many of the charges were, of course, trumped up. In Baltimore there was a law on the books that one can’t tether a horse for twenty-four hours. Someone once interpreted a horse to mean a car in modern times, so when Mrs. O’Hair left her car parked on the street for two days, she was arrested for abusing a horse.”

At times, she sees herself as a religious figure, even claiming to have been prophesied by Jesus.

Robin left me in the bookstore, where I browsed among the T-shirts, the coffee mugs, and the many books and pamphlets for sale, most of which seemed to have been written by Madalyn. In addition to her weekly cable television show, her many public appearances, and her prolific interviews, Madalyn writes much of the monthly magazine and an Insider’s Newsletter for members. And indeed, when she finally invited me into her office for a talk, the blast of verbiage left me feeling like I was being showered with a fire hose.

“I feel that Madalyn Murray O’Hair doesn’t belong to the public, only her public activities do,” Madalyn told me when I asked her to reflect on the 25 years since the school-prayer decision. “My life is my own. It doesn’t do anybody any good, anytime, anywhere for anyone to look back and say I’m going to reevaluate. What good does that do? The answer is not a gawddam bit of good!

“I do think we’re in a steady retreat. There’s an absolute steady retreat into what I call a neofascism—but it’s really old-time fascism—into a robber-baron society and a religiously dominated society, and that’s not cyclical, because they have new weapons at hand now, mainly communications technology with which they can rapidly disperse ideas . . .”

She was off. Like most people who have been interviewed too many times, Madalyn had learned the art of avoiding questions; in her case, she bulldozed right through them with her massive opinion-machine. (“I am convinced that the pope should be arrested tomorrow for crimes against humanity. Just for the fact that he goes out and he tells women to breed indiscriminately, get one in the oven tonight, to be fruitful and multiply. He should be put in a cage.”) As she argued her points, I absently studied the awards and plaques that have been given to her by various free-thought societies. Next to the door was a framed law degree from the South Texas College of Law. The extent of Madalyn’s education, like practically everything else in her background, is a matter of dispute. She likes to be called Dr. O’Hair and has claimed on occasion to have attended as many as 23 schools and 11 colleges. “Compared to most cud-chewing, small-talking, stupid American women, I’m a brain,” she once told Life. “We might as well admit it, I’m a genius.” “My degrees are primarily in history and law,” she vaguely informed a student audience. Later she boasted of an “alphabet of degrees—B.A., M.A., LL.B., M.P.S.W., Ph.D., J.D.” Her erudition is frequently remarked upon in the press. She has spent “more hours in college than many professors,” said Esquire, which noted that she had a degree from the Warren G. Harding College of Law (no such institution is listed with the American Bar Association). Except for the 1952 law degree from South Texas, an LL.B. that was later automatically converted to a Juris Doctor when the terminology changed, most of the other degrees appear to be imaginary—although that is a subject Madalyn foreclosed with her vigorous refusal to discuss anything personal. It is known that she took the bar exam, but she has never been admitted to the practice of law.

“People talk constantly about the problems of the world, but they don’t get down to basics,” Madalyn was saying. “What are you going to do with the shit? Five billion people have a bowel movement every day! Just what are you going to do with it? Let’s go ahead and ask the pope, ‘Do you want it all accumulated and put in front of the Vatican?’ ”

I finally had the opportunity to ask about a curious bronze statuette on her desk depicting two animals copulating. That set Madalyn off on a discussion of the Judeo-Christian suppression of natural sexual impulses. “I know where religion came from, and don’t ask me to talk about it, I’ll put it out in a paperback soon, but part of it has to do with human sexuality. So, one of the things that I have been collecting over the years is those things that would show humans an understanding of the need for a recognition of sex and its normal and natural place, and here is one of them,” she said, handling the statuette. “Here is an absolutely beautiful—they’re bears, I guess—example of sex in its place.” She sighed fondly. “I love them, don’t you? They’re forbidden.”

The circumstances of Madalyn’s background and early life are cloudy and bitterly disputed. A 1964 Saturday Evening Post article on the woman who then called herself Madalyn Mays Murray states that her father’s ancestors settled in the Massachusetts colony in 1650. Since then, Madalyn has given the date as 1611, although the Pilgrims didn’t arrive in Plymouth until 1620. Her younger son, Jon Garth Murray, now says that the Mays family first appeared on American shores in the person of the Reverend Mays, a chaplain on the second ship to arrive at the Jamestown colony. In any case, eighteen generations later, on Palm Sunday in 1919 in Beechview, a suburb of Pittsburgh, Madalyn was born, the second child of John and Lena Mays. According to Madalyn’s elder son, William Murray, Madalyn’s mother tried unsuccessfully to abort the child by jumping out of a second-story window. “Even Madalyn’s birth had a bizarre element,” William wrote in his score-settling autobiography, My Life Without God. “Grandmother swore years later that Mother had been born with an unusual dark membrane covering her whole body. It resembled a black shroud, and Grandmother claimed that the doctor at hand had said it was very unusual, though he offered no explanation. He gave a portion of the membrane to her, and Grandmother kept this odd keepsake for many years.”

Madalyn says that her father, whom she called Pup, was a wealthy contractor. William Murray says his grandfather was a “good carpenter, but the man never filed a tax return in his life.” Madalyn has written, “We have always been affluent. I grew up in Cadillac cars, commodious homes, with linen damask tablecloths and heavy silver and oriental rugs and a concert-grand Steinway piano. I had fur coats and diamond rings and designer dresses.” Elsewhere she states, “The chauffeur of our Rolls-Royce was black and shiny, and he rode me on his shoulders.” William contends that the chauffeur was a friend who brought food to the Mays family when Madalyn’s father was broke. After going bankrupt in the construction business, William writes, Pup opened a roadhouse that served as a brothel and turned to rum-running during Prohibition.

Madalyn’s mixed feelings about her father may be seen in her various statements about him over the years. She has been quoted, in her broad accent, as calling her father a “Nazi and a rayshist too.” On the other hand, she also has described Pup as a benevolent capitalist. “He was the only construction man in Pittsburgh then who went to the union for his ‘journeymen’; paid union wages.” Later, when her parents came to live with Madalyn, she and Pup waged an ongoing war. The last words she said to him before she slammed out of the house to run an errand were “Oh, I wish you would drop dead.” When she returned home, she found her wish had come true.

Her feelings about her mother were never mixed. Her mother was a “cowed, whipped dog.” “I do think I have resolved any kind of oedipal conflict I may have had in relation to my father,” Madalyn once told a student audience. “We had a very normal relationship. Now, I hated my mother’s guts.” According to William, Madalyn didn’t speak to her mother for the final five years of her life and did not attend her mother’s funeral.

In 1923 Madalyn Mays was baptized in the Presbyterian church. The story she has told many times is that she read the Bible cover to cover one weekend while she was still in grade school, “and I was totally, completely appalled, totally turned off, filled with repugnance.” She was twelve or thirteen at the time. “I came away stunned with the hatred, the brutality, the sado-masochism, the cruelty, the killing, the ugliness. Oh, I suppose that words like ‘sado-masochism’ were not in my vocabulary at the time, but I could see the obvious lies, the disgusting stories.”

The precocious young scholar who read those passages turned to her parents for advice. “I went in and said to my dad and mother, ‘Do you know what’s in the Bible?’ and for the next couple of weeks I would read little things to them. My mother just drew herself up and said, ‘That’s not in my Bible.’ That ended the discussion. I never accepted the Bible after that date at all. I refused to go to Sunday school. I refused to go to church. What were they going to do, hang me by my thumbs? That ended it right there.”

Despite that childhood apostasy, Madalyn, according to William, listed in her high school yearbook her life’s ambition as serving God for the betterment of man. Later, she would attend Ashland College, an Ohio school affiliated with the Church of the Brethren. Whatever the truth of her early relationship with religion, she obviously was drawn to spiritually charged environments.

In October 1941, at the age of 22, still a virgin, she eloped with a man named John Roths. Their marriage was interrupted by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor two months later, which inspired Roths to join the Marines and his wife to sign up with the Women’s Army Corps. Madalyn says that she served as a cryptographer on General Eisenhower’s staff in North Africa and Italy. (Archivists at the Eisenhower Library, who have personal records and directories of the general’s staff, could find no trace of a Madalyn Mays or Roths.) “In letters home she expressed confidence in an Allied victory because ‘God is on our side,’ ” William Murray writes in his autobiography.

“Mother always relished telling one story in particular about her time in the army,” William continues. “Though I doubt it ever happened, it illustrates the sort of grandiose ideas about herself that her army experiences somehow fostered.

“While she was in Rome, serving on General Eisenhower’s staff, she and some friends went out for a night on the town. After a more or less conventional round of dining and drinking, according to Mother, they arrived at the Vatican around three o’clock in the morning. Drunken and rowdy, they nevertheless gained entrance to St. Peter’s Basilica by bribing a Swiss guard. Once inside, with champagne bottles in hand, they made their way to a room where the three-tiered crown used in papal coronations was on display in a glass case. Mother never said how, but she claims they managed to remove the crown from its case. Thereupon they proceeded to act out a mock coronation of my mother as the first female pope. If true, Mother’s knack for attention-getting theatrics was already fully refined.”

It was in Italy that Lieutenant Madalyn Roths met William J. Murray, Jr., an officer in the Eighth Army Air Corps. Murray was a wealthy, married Roman Catholic from Long Island. “They became intimate,” his son and namesake writes, “and I was conceived in September 1945, the same month that Japan officially surrendered.”

Murray’s paternity was later established in court. Madalyn told her son that Murray said his religion forbade him from divorcing his wife and marrying Madalyn—who was, of course, still married to Roths. To compound the misery for Madalyn, she discovered when she returned from the war that her parents had moved into a shack with no electricity or running water. “She soon learned that her father had spent on booze all the money she had sent home for savings,” William Murray writes. “The whole family was destitute, she was pregnant, and her husband—not the father of her child—was expected home anytime. I believe it was during this period, as she was pacing the dirt floor of that shack and mulling over the dismal outlook for her life, that her extreme anti-God views were born.”

When Roths returned, he gallantly offered to stay with his wife and raise the child as his own, but Madalyn declined and proceeded to sue him for divorce. “By this time Mother’s antagonism toward God had reached an advanced stage,” Murray notes. During a violent electrical storm, Madalyn suddenly announced to her parents that she was going out in the storm “to challenge God to strike me and this child dead with one of those lightning bolts.” The pregnant Madalyn stood in the rain waving her first and cursing God. “You see, you see!” she cried when she returned inside. “If God exists, he would surely have taken up my challenge. I’ve proved irrefutably that God does not exist.”

Her son was born on May 25, 1946. She named him William J. Murray III, and soon after that she began calling herself Madalyn Murray—although she and Murray never married. Like his mother, baby Bill, as he was called then, was baptized in the Presbyterian faith. Several years later Madalyn bore a child by another man and named that child Jon Garth Murray. She baptized him in a Methodist church. “It pleased their grandparents,” she explained, “and I figured the kids would think it was like any other water splashing on their heads.”

The Mays-Murray clan, consisting of Madalyn, her parents, her elder brother, Irv, and Bill, moved to Houston in 1949, where Madalyn worked as a probation officer for Harris County and studied law in night school. In 1952 Pup migrated to Baltimore, following a job prospect, and the rest of the clan soon joined him.

Madalyn found work in various jobs—she says she had been a model, a waitress, a hairdresser, a stenographer, a lawyer, an aerodynamics engineer, an advertising manager, and a psychiatric social worker. During that period she turned to radical politics. She attended meetings of the Trotskyite Socialist Workers’ Party in 1957. In 1959 she applied for Soviet citizenship. Getting no response, the following year she and her two children traveled to Europe on the Queen Elizabeth with the intention of defecting to the Soviet Embassy in Paris. “The Soviet Embassy didn’t know what to do,” William Murray says now. “It was the first time they ever had anybody trying to defect to them.” Madalyn Murray and her sons returned to Baltimore in the fall of 1960, and Madalyn immediately filed her historic suit against the Baltimore schools. According to William, the school-prayer suit was little more than a ploy to persuade the Soviets to accept her.

The suit Madalyn Murray brought in her son’s name took three years to reach the U.S. Supreme Court. During that time the Murray family was the object of intense harassment. There were death threats. The house was egged. Her flower beds were destroyed. The cat was murdered. Mail came to the house in canvas bags. Much of it was hate mail, but some of it contained money—enough for the Murray family to live comfortably, according to William. Madalyn fanned the hysteria with her own provocative words and actions. “We find the Bible to be nauseating, historically inaccurate, replete with the ravings of madmen,” she wrote to Life magazine. “We find God to be sadistic, brutal, and a representation of hatred, vengeance. We find the Lord’s Prayer to be that muttered by worms groveling for meager existence in a traumatic, paranoid world.”

On May 15, 1962, Madalyn was working for the Baltimore Department of Public Welfare when she decided to appeal the school-prayer suit, which she had lost at the Maryland Court of Appeals level. “Twenty-four hours after I had filed in the United States Supreme Court, I was fired from my job for ‘incompetence,’ ” Madalyn says.

All of her life, Madalyn had yearned for understanding. One evening in Baltimore, as she sat alone in her basement library, trying to decide whether to press ahead with the lawsuit, she reflected on the sense she always had felt of her separateness. “When we had first moved into those row houses in Baltimore, I think that I had picked one out for purchase deliberately, in the hopes that I could be ‘like everyone else.’ I had wanted so desperately to fit in,” she recalled in Bill Murray, the Bible and the Baltimore Board of Education. “I could not engage in conversation about which bleach was the whitest for the wash. I never gave a damn about the chlorophyll in toothpaste. The idiotic idea of back fence visiting left me completely cold. None of my work had ever taken up even a fraction of my thinking processes and too often I would pace that basement library floor like a lioness caged, the wrap of loneliness, of aloneness, always about me.”

“I had just wanted one person somewhere, sometime, to understand me and I had never found any.”

Her parents had not. Nor had her first husband or any of her lovers. “I just want a man,” she complained in her 1963 Playboy interview, “a real, two-balled masculine guy—and there aren’t many of them around, believe me. But I do want somebody my own age, and somebody who has brains enough to keep me interested and to earn enough money to support me in the style to which I’ve become accustomed. . . . I want a man with the thigh muscles to give me a good frolic in the sack, the kind who’ll tear hell out of a thick steak, and yet who can go to the ballet with me and discuss Hegelian dialectic and know what the hell he’s talking about. I want a strong man, but a gentle one.” For a while she thought she might have found her ideal companion in Richard O’Hair, the ex–FBI informer whom she married in Austin in 1965, a man who was “both cruelty and love, patience and anger, ignorance and knowledge,” as she described him, but it was his cruelty that landed him in the Travis County jail for aggravated assault against Madalyn. William Murray says that she intended to divorce O’Hair until she learned he had terminal cancer, then she hung on to him for his pension. The disappointments in her sex life may have colored Madalyn’s attitude toward religion, Murray believes: “It is my opinion that my mother’s maniacal campaign to remove all reference to God in public schools and government . . . stems back to this issue. Madalyn Murray was mad at men, and she was mad at God, who was male.”

Shortly after moving to Austin, Madalyn and Richard O’Hair formed Poor Richard’s Universal Life Church to dramatize the folly of tax exemptions for religious institutions. Richard was the “president, pastor, and prophet,” and Madalyn was the bishop. Unlike her other organizations, Poor Richard’s church never did gain a tax exemption; nonetheless, Madalyn took to wearing a clerical collar for effect.

Madalyn’s obsession with religion leaves some other atheists scratching their heads. “Don’t you really think she is a religious person?” asks Charles Dews. “If she didn’t care tremendously about all that biblical stuff, why would she spend so much time and effort refuting it?”

It is certainly true that religion defines Madalyn’s life just as powerfully as it does the life of a priest or a television evangelist, although in Madalyn’s case she finds her identity in resisting belief instead of accepting it. At times, she acknowledges herself as a kind of religious phenomenon, even claiming to have been prophesied by Jesus in Matthew 12:42 and Luke 11:31: “The queen of the south [i.e. Austin] shall rise up in the judgment with this generation, and shall condemn it.”

“My mother is a cult leader, in case you haven’t noticed,” said William J. Murray III, as he raced toward McKinney to deliver his Christian testimony at a crusade in the junior high school. “She makes Reverend Moon look mainstream.” Murray is a sandy-haired man with Madalyn’s light-green eyes and a similar tendency to speak in diatribes. Since Mother’s Day, 1980, when he announced that he had found God, William Murray has been preaching salvation and telling the world about life with America’s most famous atheist.

In the trunk of Murray’s Mercury were several boxes of books that he would sell after his testimony. Murray is the author of four books, including My Life Without God and Nicaragua: Portrait of a Tragedy. These days he divides his efforts between evangelism and soliciting private aid for the contras and other anticommunist guerrilla organizations.

William has often voiced the hope that his mother would repent. In his fantasies he sees his mother “walking up the aisle of a church as I am at the podium giving the invitation for salvation.” Madalyn refuses to discuss her elder son’s conversion. “Bill simply got fed up with being poor, and he has sold out to the highest bidder: religion,” she observed when she first heard the news. Years later she would only comment, “My son is disturbed.”

Sitting on the stage, William listened as Paul Jackson, a Little Rock evangelist, introduced him to the half-filled auditorium. It must have seemed an odd moment for a man whose life was changed in another junior high school in September 1960, when his mother went to register him for the ninth grade and overheard the students praying aloud. The lawsuit that followed would make Madalyn Murray a household word. Fame came to her, and eventually fortune arrived as well. But Bill had to continue his life in the Baltimore public schools. “He was pummeled, hit, shoved, pushed, tripped,” his mother once wrote. “A favorite trick became that of spitting in his locker through the air slots.” Once a group of thugs cornered him in a barbershop and serenaded him with “Jesus Loves Me,” and when he tried to escape, they shoved him in front of a city bus.

And yet now William Murray renounces the atheism that he had suffered to defend. “My conversion was not a reaction to my mother’s being an atheist,” he contends. “It was a reaction to the total, swirling chaos that surrounds everything that has to do with my mother. When I was eighteen years old, my mind was totally scrambled.” He had already fathered a child, Robin, whom he later left in his mother’s care, using an old mailing list to pay off Madalyn for her trouble. After serving in the Army, he went to work for Braniff Airlines as an operations agent, later working his way up to manager. In 1975 he decided to rejoin his mother and his daughter in Austin, to “help with the family atheist business. All of a sudden I was back in all this irrationality—the screaming, the hollering, the profanity, the drinking. I started to drink heavily myself. When I finally left Austin in October of 1977, I was in total emotional distress. I got in a car and drove to Tucson, Arizona, and opened up a bookstore.”

Murray drifted to San Francisco and went back into airline management. During that period he began seeking God, partly because of the influence of Alcoholics Anonymous. “But I was praying to a god I didn’t know. I said, ‘Please, God, get this garbage out of my mind about my mother. Let me walk away from my past and do whatever it is I need to do.’ It took me two years after I had said, ‘Yes, I want to believe that Jesus is the Christ,’ to convince myself that that’s what I believed.

“Some here would say, ‘That’s all fine and good, William Murray, but how can you say all those terrible things about your mother?’ ” Murray told the audience in McKinney. “Well, I’ve tried to tell this story without saying a single derogatory word about anyone. I soon found out it was impossible to tell the story without the truth. That doesn’t mean I don’t love my mother. I don’t love the one who reaches up from his fiery pit to direct her, but I can and do love my mother. Because I want you to listen very closely to what I am going to say. She is no different than a single person in this place tonight before they accepted Jesus Christ as their personal lord and savior. She’s just another sixty-nine-year-old white-haired woman that needs Jesus.”

Madalyn and her son Jon Garth were in a television studio taping their weekly cable television show when I came in and took a seat behind the crew. Madalyn glowered when she noticed me. “You’re really dogging us, aren’t you?” she said when the camera blinked off. She combed her hair in furious strokes and trapped it in a yellow hair-band. Jon Garth glanced away. He had invited me to the taping.

“Hello, I’m Madalyn O’Hair,” she suddenly said with a broad smile when the red eye of the camera opened again. It was easy to see the charm she has in store when she chooses to call upon it and easy to see as well her courageous, witty, but also bitterly sarcastic intellect. Her intelligence is real, despite her gruff nature and the fabrications of her background. Tonight she and Jon Garth were discussing the recent purported appearance of the Virgin Mary in Lubbock at a small church that Madalyn labeled a “Texas Lourdes among the mesquite.”

“Two different cripples jumped out of their chairs, and people cried, ‘They’re healed, they’re healed!’ ” Jon Garth reported. Except that when the media got to them, these individuals said that they were in wheelchairs for other purposes—they could walk perfectly fine.”

This has been one of the valuable functions of the American Atheist Center, exposing the credulousness of mistaken believers and the occasional religious fraud. With an increasingly conservative Supreme Court, Madalyn acknowledges that the ground-breaking lawsuits are mostly a part of the past. Indeed, since the school-prayer decision, her victories have been scattered and rather marginal. She did succeed in preventing Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin from taking a televised communion on the moon. In O’Hair v. Hill, which became one of her most important victories, she sued the State of Texas over a constitutional provision that anyone holding an office of public trust be required to believe in a Supreme Being. That requirement is no longer enforced. On the other hand, her campaigns to eliminate tax exemptions for churches and to remove “In God We Trust” from the coinage have failed.

In the past, Madalyn has claimed as many as 100,000 members in her organization. If that were true, the $40 annual dues would exceed by more than five times the $750,000 budget of the American Atheist Center. Sometimes Madalyn uses the more ambiguous figure of 60,000 or 70,000 “families.” When William Murray resigned from the center, he said that the organization’s mailing list comprised only 2,517 names, less than half of whom were actual members. “If I headed the atheist movement for twenty years and had only twelve hundred and forty members, I’d look for something else in life,” he said in 1980. The latest official numbers are 55,000 members representing 45,000 families. Brian Lynch, the former treasurer of American Atheists, whom Madalyn fired for alleged sexual misconduct (he emphatically denies the charge), says that the actual membership is about 2,400, “the highest total she’s ever had.” Lynch continues, “That’s pretty pathetic considering that there are somewhere between eighteen and twenty-three million atheists in the United States and that when you mention atheism to most people, the only name they can think of is Madalyn Murray O’Hair—a loudmouth who has a bad family life, communist ideas, and a negative personality. She’s brought atheism into a position of intellectual disrepute, accomplishing in only twenty-five years what churches haven’t been able to accomplish in centuries. I think she ought to get a check from the pope.”

The checks Madalyn counts on come from the estates of deceased atheists. Lynch maintains that Madalyn’s organizations (besides the American Atheists, there are the Society of Separationists and the Charles E. Stephens American Atheist Library and Archives) took in $1.9 million, most of it from estates. “Madalyn told me she learned from Jerry Falwell that if you create a crisis every month, people are more likely to respond with money,” says Lynch. Although Madalyn occasionally does report bequests to her members, it’s also true that her complaints about money are legendary. Her newsletters are filled with urgent requests for funds. “In a continuing way, I feel like an old dog outside the stoop of your house, waiting for you to throw me a well-chewed bone, devoid of the meat,” Madalyn complained to her members. Frequently she has told her employees that she cannot meet their payroll that month. At the annual American Atheist convention she hectors her loyal followers about the need to include her organizations in their wills. “Madalyn is not an atheist activist,” wrote G. Richard Bozarth, a former employee. “She is an atheist mendicant.”

Now the camera shut off again while a trailer ran, promoting the upcoming atheist convention in San Diego. Madalyn’s face went slack. It was then I saw the frightened look in her eyes once more. It’s an expression her friends know well. “Yes, I know what you mean,” Frank Zindler told me. “I think it’s because she’s been betrayed so many times. Madalyn does indeed have to worry about physical assaults and betrayal. Fear is not an irrational response given what’s happened to her over the years. Also, Madalyn is very sensitive to the reality of mortality.” Charles Dews, a political activist in Austin who once worked at the American Atheist Center, remembers the first time he saw “that scared look” on Madalyn’s face. “We were both in the employee kitchen, and she began talking about feeling ill,” says Dews. “She was worried that she was not going to live much longer. There was a vulnerability about her that I wasn’t expecting. It seemed to me that she must have lived a hard life, a hard life and an empty life—not because her life is not full of God but because she has no real friends. I intuited something that made me feel really sad. It wasn’t that she imagined that she was going to hell or anything like that. It was that she had created a nothingness out of her life.”

Madalyn turned to watch the convention promo on the monitor. At that moment it was advertising the marvels of San Diego, which include the famous zoo. A female orangutan appeared on the screen, and Madalyn suddenly guffawed. “Well, look at that,” she said. “The Virgin has just made another appearance.”

I was sitting in the nicely appointed office of Jon Garth Murray, who has succeeded Madalyn as the president of the American Atheists. “Most cause-people think that part of being a dissenter is that you need to be poor or to look poor,” Murray said. “Madalyn and I and Robin just don’t fit into that role.” Murray, who is 34, has dark brown eyes, a moustache, and the mulish jaw and sprinkle of freckles that are his mother’s mark. His radio was set on an easy-listening station. On a credenza behind him was a photograph of beaming Madalyn cuddling her late beloved dachshund, Keegan. “We’re accustomed to good food, to eating in dining rooms with tablecloths, good dishes, a good bottle of wine. Even when we go out for lunch, we go someplace nice. You’d never see us at McDonald’s or Burger King, that’s just not our lifestyle. All of us have nice clothes. My suits cost a minimum of five, six hundred dollars. My shirts are custom made; my ties are all silk. We have a nice house in Northwest Hills, nice automobiles—we get a tremendous amount of flak over the fact that I drive a Mercedes, Madalyn drives a Mercedes, and Robin drives a Porsche. We’ve been around the world three times.”

One of the complaints that atheists have about the Murray-O’Hairs, as the triumvirate is called, is that they run the center as a family business. Jon Garth is not apologetic about that. “When it comes to ‘cause’ organizations,” he once wrote, “democracy kills.” The Murray-O’Hairs live together and tend to spend all of their time—seven days a week—at the center. “At lunchtime the three go out together, generally in three different cars,” says Charles Dews, “and of course they come back in three different cars. I used to wonder about that. Then I realized it’s probably the only time they ever have to be alone.” Madalyn has said, “I work full time on a volunteer basis for the American Atheist Center—that is, without salary.” Yet the Murray-O’Hairs obviously live a luxurious life. Jon Garth says that his lifestyle is no different from that of Jerry Falwell or Jimmy Swaggart. “I kind of understand somebody like Swaggart,” he says. “I understand why he has the mansion, the limos, the Rolexes, and so on. He’s in with a particular set of folks, and he’s got to compete. The people in his church are happy for him to do that. It’s just the outsiders who don’t understand.”

“People say that one of your mother’s goals is to see you elected president before she dies,” I said.

“Yeah, it is,” Jon Garth acknowledged. “She would like to see me run for office. I haven’t ruled it out.”

I asked him what his politics were.

“I don’t think you could actually call me a communist at this time, but I’m very close to that.”

I was surprised, because all of her life Madalyn has fought her image as a subversive. Indeed, she has said, “My most exciting victory never got near the courtroom. I am the single person who disassociated atheism from communism. I taught the American people that there is such a thing as an American atheist, just as there is an American Democrat, an American Republican, an American fascist, and an American socialist.” She purged her own organization of Marxists. “The moment we mix politics with us, we’re dead. We do not pretend to be one thing when we’re another.” Her attempted defection to the Soviet Union was a deeply buried secret.

In 1970, after the student movement had made leftist politics more acceptable, Madalyn began calling herself an anarchist. In 1976 she contemplated a race for governor of Texas, but turned her attention to running for the Austin City Council instead. She received six percent of the vote. Undaunted, Madalyn briefly considered running for president. Instead, she became the chief speech writer in the 1984 presidential bid of pornographer Larry Flynt, the publisher of Hustler magazine. It was, in many respects, an odd alliance. Only a few months earlier Flynt had declared himself “saved” and had returned to his native Kentucky to be baptized in Stenson Creek. “If elected,” he said after announcing his candidacy, “my primary goal will be to eliminate ignorance and venereal disease.”

Flynt’s campaign was cut short by his imprisonment for contempt of court when he refused to disclose the source of secret tapes he had released in connection with the drug arrest of carmaker John DeLorean. While Flynt was in prison, Madalyn apparently got him to sign over a power of attorney, giving her and Jon Garth “every cotton-picking thing that he owned, all real, personal, and mixed property,” including Hustler magazine. Madalyn privately estimated the fortune at $300 million. This coup was blocked by Flynt’s brother Jimmy, who filed suit in Los Angeles for a conservatorship of Flynt’s estate. By the time Flynt got out of prison, he had apparently changed his mind and decided to keep his fortune for himself.

“My gawd, you’re persistent!” Madalyn yelled at me as she came into the office to deliver a message to her son. She walked out of the room, then abruptly returned. “You’ve got no business writing this story!” she shouted. “You don’t have a radical mind. There’s no way you could ever even attempt to understand what we’re trying to do here. You’re a classic liberal!”

Two weeks later, when I called her on the phone, she continued the verbal lashing.

“You’re a gawddam liar!” she told me. “It is absolutely incredible that you’re calling up people and telling them that I am a thief, and that you are telling them that we are in serious trouble with a number of government agencies, and that we’re under criminal investigation . . .”

She was angry because I had been digging into various charges, most of which had been leveled at her by Brian Lynch. Lynch maintains that the IRS is following up his assertions with an investigation into the finances of Madalyn’s tax-exempt corporations. She is also facing a civil racketeering suit in connection with a weird episode surrounding the estate of James Hervey Johnson, a deceased atheist and white supremacist who published a magazine called Truth Seeker. Even before Johnson’s death, Madalyn made a claim on his $15 million estate and went so far as to have stock certificates made up in her own printshop in the name of the Truth Seeker Corporation; she then held a board meeting of her friends and allies and voted Johnson out of power. “It’s like you and me deciding that we’re going to take over Chrysler and kick out Iacocca,” says San Diego attorney Roy Withers, who is representing the Johnson interests in this case.

As a matter of fact, I had never been much interested in doing an exposé of Madalyn’s finances, as she feared. It was the woman herself I wanted to understand. And hasn’t she cried out for understanding? The closer I came to her, however, the more she withdrew and the angrier she became. Now, as she ranted on the phone, I realized that this would be my last opportunity to talk to her.

“I think you are going to try to use my name as a vehicle to gain some attention for yourself,” Madalyn continued, bushing aside my attempts to mollify her, “because you don’t have it in you to get any attention for yourself otherwise.” Click.

I replaced the receiver. Despite her feelings toward me, I came away from Madalyn O’Hair with a sense of respect but also of sadness. I had wanted to study a life lived in defiance of convention, a life that was recklessly authentic and accepting of the consequences. But when I looked into Madalyn, that was not exactly the life I found. Madalyn stood aside from the world of belief and longing-for-belief and said it was only imaginary. She had been willing to state the awful truth as she understood it, no matter how frightening the consequences. I admired her courage. But now I saw that much of her own life was imaginary as well.

As I peeled away each layer of O’Hair, Murray, Roths, Mays, looking for the Madalyn inside, I began to have a sense of the sadness of that life. It seemed a commonplace observation about her, one that her detractors and even her friends had made, but I saw at last that Madalyn was a religious phenomenon, in the same way that antimatter is an expression of matter. She was a black hole of belief.

Long ago Madalyn understood the source of her power. She is a mirror of doubt. Holding up that mirror to America, she had changed our country and shaken our ideas about who we are. Now I had glimpsed how fragile was her own identity. She had made us examine our beliefs perhaps at the cost of her own.

But, “what the hell,” as she once observed. “We have to live now. No one gets a second chance. There is no heaven and no hell. There is no ‘after’ life. You either make the best or the worst of what you have now or there is nothing. Laugh at it. Hug it to you. Drain it. Build it. Have it.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Austin