This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Ben Barnes, the former wunderkind of Texas politics, is absolutely certain that his business partnership with John Connally will work out just fine. Never mind the notices of foreclosure on their Austin headquarters. Never mind the lawsuits to collect on millions in unpaid debts. Never mind the rumors of possible bankruptcy. He and Connally, Barnes says, are going to do more deals—ones that will solve all their problems. “We’re going to make it work,” declares Barnes. “We’re going to survive, and we’re going to do some creative things. We’re going to come out of this a stronger and better company.”

At the end of an upbeat breakfast conversation in Austin, Ben Barnes walked out in long, quick strides to his gleaming white Jeep in the parking lot. As I reached up to shake his hand, a coin tumbled from my pocket. “You dropped a dime,” Barnes said. “Pick it up. We may need it.”

In the beginning, there seemed to be no way that it could miss. It was July 1981: oil was $33 a barrel, Texas was on a roll, and John Connally and Ben Barnes seemed as formidable a business combination as one could imagine.

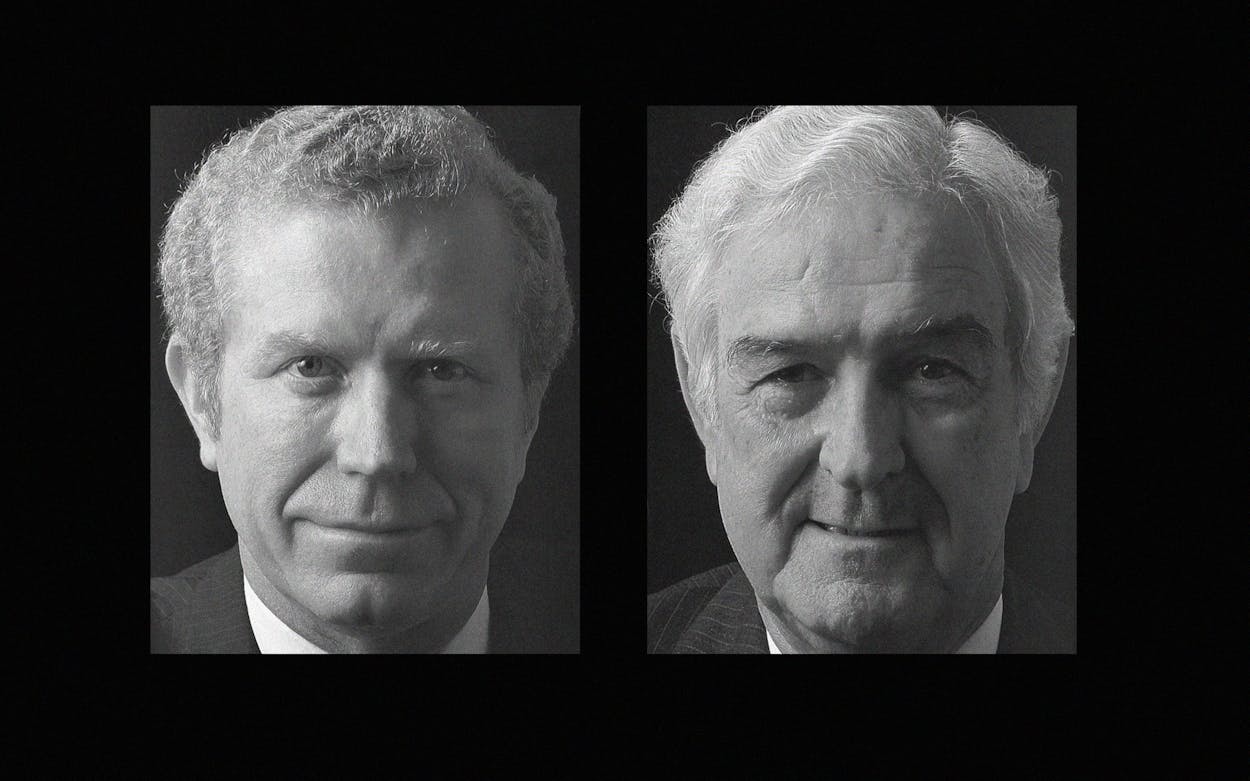

John Bowden Connally, Jr., was the personification of Texas power and influence—a piece of living political history. As a young man, he was Lyndon Johnson’s closest aide. During the first of his three terms as governor, he was wounded beside John F. Kennedy by one of Lee Harvey Oswald’s bullets. He served as Secretary of the Treasury in Richard Nixon’s Cabinet and then switched to the Republican party. In 1980 Connally ran for the presidency himself. His business pedigree also appeared impeccable. In the fifties he had been a counselor to legendary oilman Sid Richardson. In the seventies he became a partner at Vinson and Elkins, Texas’ largest law firm. He served on the boards of Ford Motor Company and First City Bancorporation; he was a confidant of corporate millionaires and Arab sheiks. This was a man born to lead: silver-haired, aristocratic, strong-willed, and proud.

Connally’s political protégé, Ben Frank Barnes, won election as state representative at 21, rose to Speaker of the House at 26 and lieutenant governor at 29. A six-three, red-haired man of enormous energy, Barnes was one of the most prolific vote-getters in Texas history, as well as a genius at back-room politics. Like Connally, Barnes ultimately failed to claim higher office. But political retirement did not diminish their standing as men of great measure. Of each it was often said, but for the unjustified stain of scandal, but for a better sense of timing, but for a dose more luck, he might have been president.

Together in business, Connally and Barnes cut a swath through the Southwest. They invested in an oil company and a drilling partnership. They bought a business newspaper, an air charter service, and half-interest in a title company. They helped form public companies to insure doctors, sell cable television advertising, and repair TV sets. They put money into a barbecue restaurant—and into a catering operation for offshore oil rigs. Their dollars followed their dizzying array of interests.

Most of all, they bet on real estate. They put up condominiums and apartments, office buildings and shopping centers. They planned a country club–health spa–conference center complex. They built in big cities and small towns. In a mere four years they started real estate projects totaling more than $300 million. Their empire stretched from East Texas to New Mexico, from the Gulf Coast to the Panhandle.

While Texas was booming, the partners were riding high. By the end of 1984 Connally and Barnes, a couple of boys from peanut country, were worth $28 million and $21 million, respectively. In August 1983 Texas Business had put them on its cover and quoted Connally in a pithy summation of the philosophy on which the two men had bet everything: “We’re beginning an era of prosperity like America hasn’t dreamed of, and Texas will be at the forefront of it!”

They couldn’t have been more wrong. As the Texas economy soured, so too did the fortunes of the Barnes-Connally partnership. Just as Connally and Barnes had been symbols of boom-time prosperity, so they now stand for the harsh reality of post-bust Texas—a world in which oil sells for $10 a barrel, real estate values fall, and banks no longer hand out money. Connally and Barnes bet everything on the ultimate Texas myth: that tomorrow would always be better than today. Now, Ben Barnes says, they are victims of their faith.

But that is only part of the story. Theirs is the stuff of classic tragedy, for John Connally and Ben Barnes are victims not merely of their stars but of themselves. Connally and Barnes entered business believing that the gifts that made them extraordinary politicians—vision, decisiveness, a wealth of personal contacts, the ability to get people to do things their way—would make them successful businessmen. In fact, this was a large measure of their undoing. Their willingness to bet on instinct, to surround themselves with loyalists, to remain above mind-numbing detail—the very talents that made them bold political leaders—have drawn them into a business quagmire. In politics, their optimism and persuasiveness won votes; in business, those qualities have kept them from confronting reality.

Today John Connally, 69, and Ben Barnes, 48—the two most able Texas politicians since Lyndon Johnson—are under siege. Lenders have declared them in default on more than $60 million in loans. They owe hundreds of thousands in back property taxes. They face a stack of lawsuits from unpaid creditors. They are in bitter disputes with formerly intimate business partners. They have been replaced as lead partners of their two largest development projects. Once, financial institutions came to them with offers to lend money; now, they must fight for more time to pay it all back. There has been a personal price as well: according to financial statements, during 1985 Connally’s personal net worth fell by $7.2 million, Barnes’s by $6.7 million.

John Connally and Ben Barnes are risk-takers, cut from the mold of the old-fashioned wildcatter. A continuing boom might have covered up their mistakes. The bust left them nakedly exposed. In days past, such daring built Texas. Now it has left the state littered with tales of lost fortunes. Connally and Barnes were going for broke. As things stand today, that’s just how they might end up.

The Mantle of Power

John Connally and Ben Barnes had always been the team. Their alliance dated back to 1961, when Barnes, as a 23-year-old freshman legislator, told Connally he would support him for governor. Barnes had boarded the train early. Back then, Connally, who was known as “LBJ: Lyndon’s Boy John,” had but 4 per cent in the polls. There was no quality John Connally valued more dearly than loyalty, and he rewarded Barnes’s commitment. Upon Connally’s election, Barnes became his floor leader in the House. Three years later Connally appointed House Speaker Byron Tunnell to the Texas Railroad Commission, opening the job for Barnes.

The two men shared modest small-town roots. Connally grew up thirty miles southeast of San Antonio, near Floresville, a tiny town where a four-foot concrete statue of a peanut adorns the front lawn of the county courthouse. His parents began as tenant farmers. Barnes grew up in the Central Texas towns of Comyn (population: 27) and DeLeon (population: 2478), where his father was a farmer and pipeliner.

The roles they would play together in business were cast in politics. Connally was the brilliant idea man, tough and aloof. His avowed motto: it’s better to be feared than loved. Barnes was the consummate salesman, tirelessly charming, a backslapper. Boots parked on his desk, unlit cigar jammed in his mouth, he exuded power. While Connally commanded attention, as a man of rank would from his subordinates, Barnes drew it naturally, as an unquestioned first among equals.

By holding the loyalty of the business establishment, they helped for years to keep Texas a one-party state. They were the last to wear the mantle of power passed from Sam Rayburn and Lyndon Johnson. When Barnes ran for reelection as lieutenant governor in 1970, Johnson emerged from retirement to address a Barnes fundraiser, at which he compared the Young Turk to Thomas Jefferson and Franklin D. Roosevelt. “Each of those wound up leading this country,” said Johnson. “ . . . You and I know that Ben Barnes is going to lead it too.”

It was not to be. Neither Barnes nor Connally was to attain higher elected office. Part of the reason was another experience they shared: the taint of scandal. Barnes was never charged with wrongdoing in the Sharpstown bank scandal, Texas’ Watergate. But headlines linking him to the case and a throw-out-the-rascals mentality doomed his 1972 gubernatorial candidacy, previously a sure bet. Connally’s stain was the milk fund; he was acquitted on charges of taking a $10,000 bribe while Treasury Secretary as payment for urging Richard Nixon to raise milk price supports. Connally’s last political hurrah came in 1980, when he ran a disastrous race for the Republican presidential nomination. Despite spending $12 million, he won only a single delegate.

Connally returned to Vinson and Elkins in Houston, where he was prized as a rainmaker—a man who brought business to the firm. Nearing retirement, Connally planned to work there only part time.

Barnes, after his defeat in 1972, had moved to the Central Texas town of Brownwood to become partners with builder Herman A. Bennett. In 1980 Barnes helped Connally shut down the presidential campaign. Inevitably, the two men spoke of the future. Together in politics, they had reshaped Texas; imagine what they could do in business. On July 9, 1981, they signed an agreement to form the Barnes-Connally Partnership. They were a team once again.

Catching the Wave

What were they after? Wealth, of course. Both men were millionaires several times over when they established their alliance. But they were hardly wealthy by the standards of great Texas fortunes. They were ready to get Big Rich.

The former governor had expensive tastes. He traveled the world, collected art, and owned an airplane and homes in four cities. He circulated in a crowd whose wealth was measured in the tens of millions; despite a net worth of about $6 million, he did not feel rich in that circle. Friends say that Connally at 64—an age when most men with his résumé would happily accept the leisurely status of elder statesman—felt he had something to prove.

For Barnes, the deal seemed to be the attraction. Barnes is a man of frenetic energy; state treasurer Ann Richards once told an audience that he reminded her of an oscillating fan. In politics, Barnes was famed for arranging four meetings in adjacent rooms simultaneously and then darting from room to room to participate in all of them. He thrived on pressure and a fast pace. In business, he would create the same environment.

Connally’s role at his new enterprise was that of senior adviser. Busy with his law practice and other concerns, Connally spent little time at the small office the partnership opened in Houston. (Characteristically, he remained behind the scenes for this article, declining several requests for an interview.)

As managing partner, Barnes ran the new company, and it quickly took on his personality. Texas was booming, and Barnes moved fast to catch the wave at its crest. This was the era of easy money in Texas. Lenders across the country wanted to get in on the Sunbelt boom, and deregulated savings and loans had new freedom to do so. Connally and Barnes had star quality; they made particularly attractive customers. “It was a pleasure to tell a banker you were president of Barnes-Connally Investments and wanted a loan,” recalls J. Edward Pennington, who held that position. “We would say, ‘If you’re interested, we’d like to have the governor come by and take you to lunch.’ Boy, those eyes would light up.”

A developer’s natural preference is to borrow every penny he can. In calmer days lenders were a brake on that inclination; they required developers to invest some of their own money. In the mania of the boom, for the right borrower, the brakes were off. Says Paul Oakes, whose company manages the partnership’s condominium development on South Padre Island, “If you’re Barnes and Connally, you can walk into a bank and say, ‘I want to do a twenty-two-million-dollar project, and I don’t want to put any cash up. But I’ll personally guarantee the note because this is a winner of a project.’ You and I can’t do a deal like that. We’ve got to put the first twenty per cent in.”

Connally and Barnes signed personal guaranties on almost all of their debts—a move they would come to regret. It meant that they could not simply walk away from a troubled project. If a project failed and a lender could not recover the full value of its loan by foreclosing on the property, the lender had a legal right to go after the partners’ personal assets for the balance. But at the time, that was an effective way to borrow more money. “I wanted to let that banker know I meant business,” says Barnes. “I was going to make it work. And if I didn’t, he could come after me personally.”

So Connally and Barnes had what every developer needs: money. They wasted no time making use of it. They began construction of condominiums on South Padre Island. They built strip shopping centers in Houston, Alvin, and Floresville—the first shopping center in Connally’s tiny hometown. They began developing a posh 1480-acre Austin residential project that would become the Estates of Barton Creek. Within a year they had begun more than $100 million worth of real estate projects—all from an office with about eight employees.

Connally and Barnes established separate legal entities for almost all of their projects. Those entities, which often included other partners, formally owned the developments. But all of the projects came under the umbrella of Barnes-Connally Investments, and they are customarily referred to, as they will be here, as Barnes-Connally projects.

Those who have worked for Barnes-Connally chortle when asked to describe the partnership’s business strategy. They say it had only two elements: profit and activity. “With Barnes, the idea was to have as many projects as possible,” says David Wolfe, who served as a company controller. Barnes worked exhausting hours, and his thin staff did the same. Wolfe recalls one period at one of Barnes’s companies when he worked 61 consecutive days.

By the end of 1983 Barnes-Connally had moved to Austin, and the value of its projects had climbed to $200 million. The federal government had recently authorized discount financing for moderate-income apartment projects. Barnes-Connally decided to build a dozen. “I had to slow Barnes down,” says Pennington. “Barnes wanted to do thirty of those apartment projects.”

Barnes-Connally was using the Herman Bennett Company—the Brownwood construction company that Herman Bennett had founded and Barnes now ran—as the contractor on most of its projects. Co-owned by Barnes and Bennett, the Bennett Company was accustomed to building eight to ten projects a year, mostly modest small-town jobs. Overnight, it was doing vastly different sorts of projects—a fourteen-story office building in Houston, a condo high rise on Padre Island—and far more of them. At one point in 1983, says Pennington, Barnes-Connally had 28 projects in various stages of development—and the Bennett Company was building most of them.

The load was too much. Projects regularly ran late and over budget. Using the Herman Bennett Company enabled Barnes to capture the contracts for building his projects rather than pay someone else. But Barnes-Connally’s reliance on the Bennett Company meant that there was no bidding to keep costs low. Barnes says overruns and missed deadlines are universal in the construction business. But he acknowledges that the construction company “was not as well run as it should have been.”

The frenetic development program, the overruns and delays, and Barnes’s inclination to invest every available penny left the partnership and the construction company perpetually short of cash. Barnes-Connally took out thirty-day loans to meet operating expenses, but it could never catch up. Loans for the next project were used to pay bills for the previous one. “The cash situation was abominable,” Pennington says. “We’d have ten crises a day. Somebody was always walking into my office saying, ‘So-and-so’s walking off the job if we don’t pay them today.’ You’d pay them and not pay somebody else.”

Pennington, a former executive with the Shelton Ranches in Kerrville, had been hired as chief operating officer in 1982 to bring order to the chaos. He was a man of numbers, a believer in pro formas, market research, and detailed budgets. But Ben Barnes acted on instinct, not numbers. Subordinates say Barnes fell in love with deals. “Ed tried to make Ben face realities,” says Mike Crockett, who worked for a year as Barnes-Connally’s marketing director. “Not many people could go to Ben and say, ‘This is a bad deal.’ Ben would come in with his silver tongue and make you think it was good.”

Operating in an era of aggressive development, Connally and Barnes weren’t interested in hearing why deals couldn’t be done. In politics, such deep-seated optimism is a plus. In business, it is dangerous. When told a project wouldn’t work, Barnes would tell his staff, “We’ll make it work.” When persuasion didn’t curb skepticism, intimidation did, says Pennington. “He has the ability to just overpower you—his size, his presence,” he says. “He hovers over you and says, ‘I’ll get it done, goddammit.’ Guys just get quiet. Just melt in their chairs. That’s the kind of confidence that gets you in trouble.”

But Barnes-Connally wasn’t filled with subordinates inclined to ask tough questions anyway. Its executive ranks were liberally sprinkled with long-trusted associates. Barnes’s son Greg for a time presided over land acquisition. A top lieutenant was Ralph Wayne, a former West Texas legislator who had been Barnes’s floor manager in the House twenty years earlier. Managing two projects was Bryan Lewis, who had run the Houston office of Connally’s presidential campaign.

A former business associate calls Barnes “the world’s best starter and the world’s worst finisher.” Barnes began a remarkable number of projects. Filling them up was another story.

Barnes hired leasing and sales agents reluctantly, Pennington says. “Barnes had a hang-up on marketing,” he says. “If we were having a problem, he’d say, ‘Well, I’ll go sell it.’ But Ben Barnes couldn’t do that every day. He couldn’t be a leasing agent, developer, and contractor for twenty-eight projects. He thought he could.” Says Crockett: “He’d come back from a trip and have a stack full of business cards, and he’d say, ‘Crockett, I sold five condominiums yesterday.’ He’d hand me a stack of business cards. In his mind, he’d sold them. Of course, we’d follow up, and those people had no intention of buying one.”

Barnes acknowledges spreading himself too thin. But he denies starting projects imprudently. “Of the projects we’ve looked at, we probably did twenty per cent of them,” he says. He dismisses much criticism as the unjustified carping of disgruntled former employees, particularly Ed Pennington. The partnership’s chief operating officer left Barnes-Connally in October 1983, and Barnes says he was fired for poor performance. Pennington, now in the real estate business in Houston, says he was fired because he opposed Barnes’s business practices.

Crockett departed in September 1984 to become the Austin marketing director for Lincoln Property, the state’s second-largest development firm. There, he has been struck by the differences in how the two companies operate. Lincoln studies for weeks a deal that Barnes-Connally would make in days. Lincoln acts only after drawing up detailed budgets. “Barnes-Connally didn’t do sophisticated budgets,” he says. “It was the Brownwood-Floresville back-room approach.”

But for a time, among those who worked at Barnes-Connally in the midst of the boom, there was a euphoria about the enterprise—a sense that they could accomplish, through brains and clout and sheer will, whatever they wanted. So much was happening—and so fast. It had the feel of . . . a political campaign. It was life on the edge. But at the height of the boom no one worried about tomorrow. “We were all bulletproof,” Pennington recalls. “The U.S. was in a slump, and Texas was going through its biggest boom ever.” The possibility of a collapse was the furthest thing from anyone’s mind. Says Pennington: “The big question was, Can you react quick enough?”

A Day at the Races

Among the employees at Barnes-Connally, John Connally was addressed formally as “Governor,” and for the most part he retained the role of lofty counselor, above the day-to-day fray. But he was a man who trusted his gut; when instinct told him to act, he was ready to make a deal.

In August 1981 Connally was at the Ruidoso Downs racetrack with his friend Houston developer Joe McDermott, when the two men noticed that the old Chaparral Motor Hotel was for sale. The twenty-year-old hotel, next door to the track in the New Mexico resort area, was badly in need of repair. But Connally wasn’t interested in the hotel building; he wanted its seventeen acres of land. The two men called a real estate agent that afternoon. At midnight, dressed in pajamas in his hotel room, Connally signed a contract offering to buy the property.

Operating under the name Alta Enterprises, Connally, Barnes, and McDermott decided to tear down the hotel and build luxury condominiums on the site. They called the project Triple Crown, and from the beginning, like many Barnes-Connally projects, it was different from anything the area had ever seen. The mountain community was a playground for West Texas; it attracted skiers in the winter, horse-racing fans in the summer, and retirees all year long. Condominium projects were scattered all over town; they tended to be rustic and modestly priced.

Triple Crown’s condos were to be expensive—the cheapest would sell for $140,000. The target audience was rich horsemen, the sporting millionaires who ran ponies at the racetrack. They would buy a condo to have a comfortable place to stay right by their horses. Indeed, the location required purchasers to have a deep affection for horses. On the floor of the mountain valley, the site abutted a practice track for Ruidoso Downs. When the wind whipped through the valley, clouds of dust blew up and visitors could detect the pungent scent of horses.

Triple Crown was not in fashionable Ruidoso, a resort town with the feel of Aspen, but in its poor cousin down the mountain, Ruidoso Downs. In the descent from one community to the other, tony shops and restaurants gave way to fast food joints, a clutch of cheap motels, and a service station with old tires piled in front. Behind the Triple Crown property was a water-filled gravel pit; locals would come to call it Lake Connally.

A more cautious developer might have built in phases—perhaps 30 units at a time. But Connally and Barnes were not cautious men. Instead of 30 units, they would build 104. And when those were built, they planned to add a fourteen-story tower, a shopping area, and a restaurant.

Construction, with the Herman Bennett Company as general contractor, began in late 1982. Although presale had gone poorly, Connally and Barnes stuck to their plans. They told their subordinates not to worry, that they and Joe McDermott would sell the condos themselves. “They knew enough people that they would personally go out and sell those things,” recalls Ed Pennington. “They were each going to sell a third of them.” Rather than catering to the market, Connally and Barnes were building to their own lofty tastes, counting on their fame, contacts, and will to make it work.

And in fact they tried. In a private plane the three men barnstormed West Texas to talk about their New Mexico real estate. They made one stop in Midland, where they hosted a cocktail party at a downtown hotel. The receptions drew crowds, but West Texans weren’t buying. Connally and Barnes might win their votes, but they couldn’t pry loose their money.

Building in Ruidoso Downs also proved difficult. Before Triple Crown was finished, its owners had exhausted their original $12.4 million loan. As they struggled to come up with more money, more than a dozen subcontractors went unpaid. Bryan Lewis, who was supervising the project for the partnership, journeyed to Connally’s home in Santa Fe. Over lunch, Lewis says, he told Connally that Triple Crown was a debacle. He remembers Connally’s response: “That’s the finest project we’ve got going.”

Triple Crown did not open until mid-1984—about six months late. At the grand opening party, Triple Crown struck guests as peculiar. Two-bedroom units had up to four separate levels, with many stairs—a feature guaranteed to discourage retirees, one of Ruidoso’s biggest markets. Master baths had Jacuzzis but no showers. And the units had open balconies. During winter snows, huge drifts would pile up on the balconies; when the snow melted, water would leak into the apartments. And in a town prized for its open spaces, Triple Crown had none. The three-story buildings were jammed onto the site. Eighteen of the 104 condos had sold during construction. When the project was finished, all eighteen sales fell through. “Had you built twenty-five of those units, even on that site, it might have sold out,” says Crockett. “To jump in and do a hundred and four of them, that’s jumping off the high board, hoping there’s water in the pool.”

Barnes now acknowledges having built a project that was too big and too expensive. “The mistake we made in Ruidoso is we should’ve phased it,” he says. “That’s the governor’s and my mistake. We built too good a product in Ruidoso.”

Local folk took note of the project’s troubles. They called it Cripple Crown. Connally, Barnes, and McDermott decided to operate the condos that were completed and furnished—less than half—as rental units. But they could not bring in enough money that way to make the expensive project profitable. In April 1985 they decided on time-sharing as a new strategy; they would sell rights to one week in a condo each year.

To market the project, they contracted with a time-sharing marketer named Marvin Israel. Israel set up boiler rooms in Irving, Austin, and Ruidoso Downs. To lure prospects for an in-person sales pitch, his staff used phone banks and letters offering gifts and vacations. Bill Skeen, who now manages Triple Crown, says the owners discovered no problems in their check of Israel’s background. After hiring him, they did find that he was instantly effective. In one month Israel sold close to $1 million worth of time-sharing.

In mid-June an assistant Texas attorney general called Skeen, alleging that Israel was attracting customers by offering prizes and “free” vacations with undisclosed strings attached. One sales letter promised a full Hawaiian vacation for two at the cost of a single airfare—which turned out to cost more than a normal fare for two. Israel also had no license to sell real estate in Texas. Moreover, he was a man with a past. The attorney general’s office had sued Israel in 1984 for an allegedly deceptive time-sharing promotion, and Israel had signed a court order agreeing to refrain from such practices.

Barnes told attorney general Jim Mattox, an old political friend, that he would halt the Texas sales operation and give refunds to anyone who had been victimized. Mattox decided to hold Israel—not the owners—responsible; when the attorney general filed a lawsuit in the case on September 13, 1985, only Israel and his associates were named as defendants.

As promised, Barnes-Connally shut down Israel’s sales operation in Texas. But it continued to allow him to operate from Ruidoso Downs. Barnes explains that Israel had promised to stop using the abusive sales tactics and that he trusted Israel. “The mistake we made is that Marvin Israel was not supervisable,” says Barnes.

The New Mexico attorney general’s office had also called. Kenneth Cassutt, an assistant attorney general investigating the matter, alleged in midsummer that Israel was—among other improprieties—still mailing flyers with the Hawaiian vacation offer. Skeen says he called Israel, who attributed the problem to a mix-up and again promised to stop. In October Skeen flew to Santa Fe to meet with Cassutt. The assistant attorney general handed him a Triple Crown sales flyer containing the deceptive Hawaiian vacation offer; it had been mailed in September. Barnes-Connally finally fired Israel and shut down the entire Triple Crown sales operation. The project was dead in the water.

Barnes says he acted “naively” and is “mad enough to break Marvin Israel’s neck.” Israel, who has filed for bankruptcy and moved to Kansas, blames his problems on a vendetta by the Texas attorney general’s office. He denies doing anything wrong. But New Mexico’s attorney general, Paul Bardacke, wasn’t primarily interested in Israel.

Unlike Jim Mattox, he was determined to hold Connally, Barnes, and McDermott responsible. “We felt they had done wrong,” says Bardacke. “We weren’t about to lay it off on some player.” Settlement talks began, but Triple Crown’s owners, in the process of trying to renegotiate their loan, were anxious to avoid any new financial commitments. Skeen acknowledges stalling for time—until the attorney general’s office last March warned Triple Crown to meet a deadline to respond or face a lawsuit the next day.

One day before the deadline, Bardacke received a phone call in his office from Jim Mattox. “He indicated he had a constituent with a problem in New Mexico,” says Bardacke. “He indicated he knew him, and would I be willing to meet with him.” Barnes called a short time later, and they agreed to a meeting on April 8 in Santa Fe. In the settlement, signed in May, Triple Crown’s owners admitted no wrong. But they agreed to pay a $15,000 fine, to allow anyone who purchased timesharing in response to deceptive mailers to get his money back, and to provide all promised gifts and vacations.

The shutdown of sales operations left Triple Crown with little income to meet the payments on its $10.6 million loan balance with Albuquerque Federal Savings and Loan. Triple Crown’s owners have made no payments in 1986; by July 1 they were $781,000 in arrears and hopeful that Albuquerque Federal would take the building back in complete forgiveness of their loan. Triple Crown owed more than $61,000 in county property taxes as well. Like its economic fortunes, Triple Crown’s foundation has also shifted. Half of the foundation repairs have been made; the rest will wait until loan talks are completed. Electricity to most of the units has been shut off to save money.

When Triple Crown was finished, John Connally took his wife, Nellie, and Mike Crockett to visit the project that had begun with his day at the races. Crockett recalls that they stood out on the balcony of Connally’s condominium. All around them were empty buildings. The gravel pit, half filled with stagnant water, lay just off to their right; dust and sand blew up into the air. But to Crockett, John Connally didn’t seem to notice any of that. He appeared to see only the deep blue sky and the distant green mountains. “Nellie, look at that,” said Connally. “Isn’t it gorgeous?”

Surrogate Father, Surrogate Son

Ben Barnes and Herman Bennett’s first encounter came in Brownwood, where Barnes, at 21, was rounding up votes in an unlikely candidacy for the Legislature. “Honest—Qualified—Sincere” was his slogan. Bennett was a successful local builder, twenty years older and impressed with the youth’s gumption.

After Barnes won the election, Bennett began to contribute to his income. Later, by matching his paltry state salary, Bennett allowed Barnes to concentrate full time on politics. Bennett raised money for Barnes’s campaigns, gave him interest-free loans and equity in his projects. He screened Barnes’s business deals to keep him out of trouble. The two men became close. Friends say the childless builder and his wife treated Barnes like a son. When Barnes made major political appearances, he seated the Bennetts next to his own parents. When Barnes married for the second time, Herman Bennett was his best man. Says Bennett, “I loved him.”

While Barnes was in politics, he worked for Bennett between legislative sessions. Bennett spoke often of how much money they could make together if Barnes would dedicate his energies to business. His fondest wish was that Barnes would return to Brownwood to take over his business.

A devout Baptist, Bennett was a man of his place. “When I get back to Brownwood, I just feel like I’m in God’s hands,” he said, driving around the Central Texas town last June. It is not surprising that Bennett feels kinship with this city of 20,000; he has built much of it: the city hall, the public library, the Brownwood Coliseum, the 3M plant, and the Gordon Wood Stadium, named for his retired friend, the winningest high school football coach in the nation’s history.

In 1972 Barnes lost his gubernatorial bid, and Herman Bennett got his wish. Barnes moved to Brownwood, and within three years Bennett made him his full partner. They were to share equally in all future deals. But Barnes also became co-owner of everything Bennett already owned—including the construction company that bore Bennett’s name.

In May 1971 Barnes’s net worth had been $84,737—and even that wasn’t cash in the bank. “Anybody who tries to make Ben out to be a rich man is just wrong,” Bennett told the Houston Post at the time. “Right now he couldn’t write a five-thousand-dollar check that wouldn’t be hotter than a two-dollar pistol.” Nineteen months later Barnes was worth $2.8 million. By the end of 1975 Barnes’s net worth had reached $5.4 million.

Bennett happily passed the reins of the operation to his protégé, naming him president of their investment partnership and the Herman Bennett Company. Bennett began spending much of his time on his four-thousand-acre ranch, where he raised champion cutting horses, and on hunting expeditions throughout the world. Bennett had started Barnes in business, and he was ready to reap the rewards. “My game plan was to semi-retire, turn it over to him and let him make me a living the rest of my life.”

The change at the top produced a dramatic change in approach. Herman Bennett, who had started out in business sanding floors, had become a millionaire slowly. He built in Brownwood and small towns like it. He put up Holiday Inns, strip shopping centers, and low-rise factory buildings. Bennett was a detail man who took on no more than he could supervise personally. With Barnes aboard, the partnership bought and sold banks and insurance companies. The number of projects increased, and the company built in bigger towns. Barnes and Bennett bought the tract near Austin that would become the Estates of Barton Creek. They borrowed more, using the cash for new deals. “I knew more people,” says Barnes. “More opportunities came our way.”

When Barnes forged his partnership with John Connally in 1981, he cut Bennett in on their deals. Barnes says he wanted Bennett—despite his talk of retirement—to supervise the new projects the construction company was building. “I never held out to know anything about construction,” says Barnes. But Bennett preferred to do other things. Several Barnes-Connally projects were the sort Bennett would never have started himself—large projects in big cities, far from Brownwood. Bennett knew little about the developments and did not even visit most of them. But he remained a willing investor. Like Connally and Barnes, he signed notes and personal guaranties to borrow money for many of the projects. His fortunes became dependent on the deals, and he admits he did not question them. Bennett trusted Ben Barnes.

By 1983 Barnes was running the Herman Bennett construction company and his partnership with Bennett from one office in Brownwood, and his partnership with John Connally from another office in Houston. He decided to move his businesses to Austin. Barnes did not believe he could build a big company from Brownwood. Besides, Barnes-Connally’s largest project—the Estates—was in Austin. From Barnes’s perspective, a single location there made perfect sense.

There was just one problem: Herman Bennett did not want to move. Barnes says Bennett was fully briefed of plans to move the company. “He didn’t want it to happen, but he knew it was happening,” says Barnes. “It was hard for Herman to realize that I should come to Austin. If I’d not come here on a daily basis, the Estates would not have gotten done.”

Bennett tells a different story. He says he was attending a cutting horse show in Fort Worth one Saturday in May 1983 when he called to check in with his office in Brownwood. According to Bennett, his secretary told him the offices of the company were being loaded into moving vans.

Bennett returned to find his offices empty. “I didn’t know, and I didn’t approve of the move,” Bennett insists. “I’ve been in Brownwood forty years. This is where my friends are. This is where I wanted to live the rest of my life. This is where I wanted to have my company. It didn’t please me one damned bit for them to move.” Says Bennett of Barnes: “I regretted I ever brought him here.”

On August 27, 1983, Bennett revoked the power of attorney that he had granted to Ben Barnes. For months Herman Bennett rarely spoke to the man he had treated like a son. The two men communicated through an intermediary.

For a time, Barnes authorized the payment of salaries and office expenses for the few employees he had left behind in Brownwood. Then his deputy, Ralph Wayne, on delivering a payment, told Herman Bennett that there would be no more checks. Wayne says they stopped because Bennett had his own business.

In November 1983 Bennett incorporated two new companies, Herman Bennett Enterprises and Bennett Construction, so that he could start over in business. “I stumbled around here for the first few months like a damned whipped dog,” says Bennett. “I decided, hell, I’d done this one time, I could do it again.”

But while Bennett ended his personal relationship with Ben Barnes, their financial affairs remained deeply entwined. In June 1984 RepublicBank sued Bennett to collect more than $23 million in overdue notes that he had cosigned with Barnes. The bank eventually dropped the suit, but the episode persuaded Bennett to end his decade-old partnership with Barnes.

The process of dividing the assets of Herman Bennett and Ben Barnes took more than a year. Their shared investments included fifty separate corporations, partnerships, and ventures. The final papers were not signed until New Year’s Eve, 1985, in the Austin offices of Barnes-Connally’s law firm. The settlement was true to type: Bennett got all the properties in Brownwood, almost entirely free and clear, and two Holiday Inns in New Mexico. Barnes got Bennett’s share of all the rest: the far-flung apartment projects, the shopping centers, the resort condominiums, the Houston office building—as well as a staggering measure of debt.

Bennett had given up millions in potential equity in exchange for freedom from the debt. Barnes signed documents pledging to pay Bennett’s share of the loans on the assets he received. Barnes could have his big cities and his big deals; Bennett had pruned his roots back to Brownwood. At last, he seemed free of the entanglement of Ben Barnes. There was just one catch: if Barnes could not pay the debt, the lenders would look to collect from Herman Bennett once again.

The Prettiest Land

When John Connally and Ben Barnes began developing the Estates of Barton Creek—one of the largest residential developments in Travis County history—the project had everything going against it. It had no streets or water rights. It was in the wrong school district; unlike other prestigious developments nearby, it was served by Austin, rather than suburban, schools. And the site, eight miles west of downtown, had terrible access. A Barnes-Connally executive spoke of the remote tract as “goat country.” Other developers called it the Mistakes of Barton Creek.

Austin is one Texas city where zoning is not an unmentionable, and there is no more difficult place in Austin to develop land than along Barton Creek. Environmentalists fear that development along the creek will pollute the Barton Springs swimming hole, Austin’s ultimate sacred cow—and the Estates borders the creek. In such a setting, none of Barnes-Connally’s problems had simple solutions. And failing to solve any of them would surely doom the project.

Barnes was undaunted. “The things that had to be done were things I’d been trained to do,” he says. “They were political in nature.” From the beginning, Barnes’s commitment to the project had been an act of faith. He and Herman Bennett bought the land back in 1974, when Austin was growing—but in the opposite direction—and Barnes struggled with loan payments for seven years to keep from losing it. Now the growth had moved his way; his faith would at last be rewarded. In 1981, with Connally by his side, Barnes began developing the land he loved. Even today he watches his slide presentation on the development with a look of wonder. “It was the prettiest piece of land I’d ever seen,” says Barnes. “In the end, it’s going to be the best thing I’ve ever done.”

Barnes solved the first problem—water—by buying a private water company and purchasing water from a river authority. A decision by the Catholic church to build a high school at the Estates eased the problem of schools.

But the thorniest problem was access. The main access to the Estates was by traveling along a narrow road through an adjoining development. Barnes wanted a new road. For a normal developer, that meant urging the county or state government to build one—a process that takes four or five years. But Barnes was no normal developer, and he didn’t want to wait. To get a new road on his land, Barnes would pass a law through the Legislature. He drafted a bill to authorize the creation of special road districts, areas that would allow property owners to issue bonds to build their own roads, then tax themselves to pay off the bonds. Then he tapped his contacts. Barnes met privately with Mark White to explain his proposal. When the governor called for a special session to consider education reform in 1984, Ben Barnes’s bill was added to the agenda. It breezed through the Legislature. Fifteen months after White signed the measure into law, Barnes created the state’s first road district and began constructing a $20 million six-lane road.

Barnes also needed another entrance, a quicker route between the Estates and downtown. The sacrosanct Barton Creek stood directly in the way. There was only one way across: a bridge. If building near Barton Creek was a difficult task in Travis County, trying to build something in the creek was practically impossible. Barnes began lobbying county commissioners.

The agenda item for the Travis County Commissioners’ Court meeting of November 19, 1984, read cryptically: “Approval of proposed Community Facilities Contract.” There was no mention of a bridge, no mention of Barton Creek, and, when the commissioners voted 4-0 to approve the item, absolutely no public discussion. Environmentalists howled when they learned several days later what had happened. But it was too late. The county would bear $900,000 of the cost for the four-lane bridge, set at $2.9 million; the Estates was to pay the rest. Barnes denies having anything to do with the surreptitious way the bridge was approved. He says he would be happy to have defended the bridge publicly because he is proud of its environmentally sensitive design. “That bridge is a masterpiece,” says Barnes. “I want to have a dedication of that bridge and invite the free world.”

Marketing the land proved more difficult than preparing it for development had been. Barnes and Connally had conceived of the project as the most prestigious address in town. They built expensive homes there for themselves, hoping to add to its cachet. In 1982 the Estates imposed a set of deed restrictions ensuring that the development would include only large, expensive homes. All lots were to be single-family residential, with houses of at least 2300 square feet. The restrictions required approval of all fences, specified roof colors, and limited each residence to two dogs or cats.

But the Estates was to be more than just homes. As always, Barnes and Connally had grand and ambitious plans. They decided to build an unusual resort complex called the Barton Creek Club. It would include a golf club—with an initiation fee of $14,000—as well as a 150-room lodge, a health spa, a conference center, and a clubhouse with three restaurants and a ballroom. Connally and Barnes even planned a common wine cellar, open only to those who belonged to the club.

The hotel market in Austin was rapidly becoming glutted. But Connally and Barnes did not intend for the Barton Creek Club to vie for guests with local hotels. They envisioned it as competing with the nation’s most famous recreational meeting facilities. The Lodge at Barton Creek was to be the La Costa of the Southwest. Construction began in early 1985. Barnes boasted that it would be “a gold mine.”

The early success of the Estates encouraged his ambitions. Opened in 1981, the first section of 100 lots—$45,000 for one acre—had sold quickly, mostly to builders who planned to put up spec houses. Austin was experiencing unprecedented growth. The announcement by Microelectronics and Computer Technology Corporation (MCC) that it would locate in Austin had fueled a land boom—particularly at the top end of the market. During 1983 the number of houses priced over $100,000 climbed by 70 per cent. Land prices spiraled, with little correlation to demand. It was at the peak of the boom, in April 1984, that Connally and Barnes arranged the purchase of the Uplands.

The Uplands was a mammoth piece of land—3280 acres due west of the Estates. It was even farther from downtown, with equally rugged terrain. For Barnes-Connally, it was extraordinarily ambitious. Developers typically do not make their profit until a project is sold out, and development of the Uplands would take at least a decade. The size of the deal daunted much larger developers.

Nonetheless, there had been competition for the land. Connally and Barnes won out by offering the owners cash: $54 million. To come up with the money, Connally tapped an old political contact: Charles Keating, the monarch of a Phoenix-based financial empire and one of Connally’s 1980 campaign finance chairmen. Keating’s company, as the financial partner, would purchase and own the Uplands. Barnes-Connally would run the development; in return, it would receive 50 per cent of the profits.

In late 1985 Barnes-Connally received the first of many city council approvals it needed to begin developing the Uplands. But Keating was growing impatient. “It just went too slow,” he says. “They had so many projects bugging them that we felt we’d be better off doing it on our own.”

In April 1986 Barnes-Connally withdrew as developing partner. Keating replaced his friend’s firm with Centre Development, a Dallas company. Barnes-Connally retained only a 20 per cent interest in the project’s profits. The move was a major blow. On their 1985 financial statements, Connally and Barnes had valued their rights to revenues from the Uplands at $7.1 million.

Projections for the club proved unreasonably optimistic. A 1984 offering statement had forecast almost 50 per cent occupancy for the 150 lodge rooms for the last seven months of 1986, with rates of $120 to $200 a day. Now the lodge is not expected to open until early 1987.

The Estates had also run into problems. The contract to build the bridge over Barton Creek came in $700,000 over Barnes-Connally’s expectations, and construction was running late. Worst of all, sales of homes and lots at the Estates had slowed to a crawl. The Austin real estate frenzy had finally ended. Several builders had been unable to sell the $500,000 spec homes they had erected and lost them to foreclosure. Five years into the project, 60 of the 212 lots in the Estates’ first phase remain unsold.

This year Barnes-Connally returned to the drawing board to come up with a downscaled master plan. The new plan proposes areas of quarter-acre lots and townhomes, multi-family buildings with up to fifteen units per acre, a shopping area, an office park, and sixteen acres for a retirement home for the elderly. Says Barnes, “You’re going to be able to have a house in the Estates for less than a half-million dollars.”

Pioneering Concepts

Two of the most ambitious of Barnes-Connally’s other real estate projects followed the firm’s pattern. Started in markets that had already peaked, the projects opened to markets that had collapsed. Built by the Herman Bennett Company, they were completed late and over budget.

Back in 1981 Ben Barnes was sure that he could make money on South Padre Island. In fact, he already had. With Herman Bennett and a Dallas developer named Pat Buell, he had built 80 two-story condominium units on Padre Island during the seventies. The developments, called Sunchase I, II, and III, had all sold out. By 1981 Mexican money was flooding Padre Island. The time seemed ripe to build Sunchase IV.

The earlier condos had been built in phases, 25 or 30 at a time; the next phase was not begun until the previous one was mostly sold. Sunchase IV was to be a fourteen-story luxury high-rise—120 top-dollar units, all built at once. It was a far bigger project—and a far bigger gamble.

Buell had personally supervised construction of the previous condo projects and used his own construction company to build them. At Sunchase IV Ben Barnes was to supervise, and he, Connally, Buell, and Bennett were each to own a quarter of the project. There were other high rises on Padre Island, but none more striking. Sunchase IV was to have an elaborate stair-step design. The condominiums would be tricky to build and expensive to buy. Next door, to complement the project, Connally and Barnes would build the $8 million, 67,000-square-foot Sunchase Mall, South Padre’s first air-conditioned shopping mall.

The problems began even before construction. In February 1982, one month before work was to start, the Mexican government instituted the first of several peso devaluations that were to wipe out a prime market for South Padre condos. But the partners already had a loan commitment of $15.5 million and a healthy presale. They decided to plunge forward anyway, hoping that things would get better by the time the building was finished.

When construction reached the sixth-floor level, Buell, on an inspection of the site, discovered construction flaws that forced a complete shutdown of the project. The construction manager was fired, and the site remained idle for more than a month. When work resumed, late payments to subcontractors prompted several to walk off the job. By July 1983 Sunchase IV was supposed to have been completed; instead, it was a little more than half-finished, and out of money to boot. Barnes and Connally returned to Sunchase IV’s lender, Manufacturers Hanover of New York, to borrow an additional $6.3 million for the overruns and additional debt service.

Barnes acknowledges the construction company made mistakes, but he blames the delays primarily on the difficulty of building on South Padre. Nonetheless, by year’s end Buell was fed up. He told Barnes and Connally he wanted out. “People on the site were not competent, in my opinion,” says Buell. He believes Barnes was too busy with other deals to keep an eye on Sunchase IV. In December 1983 Barnes and Connally signed an agreement to buy Buell out. Buell got cash and notes for $500,000 and a promise of two condominiums free and clear upon completion. When he failed to receive title to the condos, Buell filed suit and won a court judgment against Connally and Barnes.

Sunchase IV was completed in May 1984—26 months after construction began, about 10 months late. A grand opening party, hosted by Connally and Barnes on Memorial Day, drew 1200 people—but few buyers. Before construction began in 1981, Connally and Barnes had contracts for almost half the condos. But federal consumer protection laws release buyers from any obligation if such a project is not completed within two years; the construction delays triggered the release provision, and many buyers backed out. To meet their commitment to the bank to have sixty condos sold by opening, Barnes and Connally bought seventeen condos themselves.

Today, according to project manager Paul Oakes, just over half the condos—65 of 120—have been sold. The two- and three-bedroom units that remain begin at $240,000, well above the South Padre market. And for that sum, many of the condos do not even offer a clear view of the ocean; instead of sand and surf, their living rooms gaze out on the roofs of Sunchase I, II, and III.

The balance of the $21.85 million note—about $10 million—came due on November 8, 1985. Connally and Barnes had personally guaranteed the loan but didn’t have the money. When Manufacturers Hanover threatened to foreclose, Connally and Barnes filed suit and won a court order blocking the bank from repossessing the building. The move bought them enough time to borrow $400,000 to pay the bank. That ran out in March 1986. Though Connally and Barnes had put $4 million of their own cash into the project, their loan fell into default once again. Since then, Connally and Barnes have been negotiating with Manufacturers Hanover for a new loan, and the debts associated with Sunchase IV have continued to mount. Connally and Barnes have fallen behind on the $2.3 million loan used to buy the seventeen condos necessary to meet the presale commitment; the lender has been threatening to foreclose on those units since June. According to Oakes, more than $100,000 in county property taxes remains delinquent.

Barnes acknowledges that the expensive design of the Sunchase IV condos made them difficult to sell. But, he says, “if the devaluation of the peso hadn’t taken place, we’d have sold out Sunchase IV in a year’s time and made a lot of money.”

When defeated presidential candidate John Connally went to the Republican National Convention in 1980, he took one campaign aide with him: Bryan Lewis. Lewis, then 28, had regarded Connally as a hero since college, when he met him while volunteering for Democrats for Nixon. When Connally announced his candidacy in 1979, Lewis quit his job with a Houston construction company to enlist. Lewis had been with Connally when the campaign had begun; he was with him still now that it was over.

Following the convention Lewis got into the construction business, buying and remodeling homes for resale in pricey Houston neighborhoods. After Lewis had made a couple of profitable deals, John Connally volunteered to help him. The partnership was a silent one: Connally helped Lewis get financing and guaranteed his loans. But it was more than altruism; Connally was to receive half the profits.

In 1982 Lewis approached Connally and Barnes with an idea: build an office condominium building on South Shepherd Drive, west of downtown Houston. The office condo was a pioneering concept; it had not yet caught on. But it had one especially attractive advantage: it would enable the owners to get their money out of the deal fast—provided, of course, that the condos sold. Connally and Barnes formed a joint venture with Lewis, each owning a third of the project, and agreed that Lewis would run it.

When construction began in January 1983 there were clear signs that air was leaking from the Houston real estate balloon. In hindsight, Barnes acknowledges that “going to build a high-rise office building in Houston [when we did] was one of the most ill-conceived ideas in the world.” But at the time, optimism ruled the day. By mid-1984 the usual problems had developed. Construction was running late and over budget, and the Bennett Company had fallen behind on its payments to subcontractors. In August the unpaid subs walked off the job, halting the work. Near completion, the building sat idle for weeks. In the meantime, the Houston office market collapsed.

Lewis says Connally and Barnes failed to pay about $250,000 in cash calls for miscellaneous expenses on the project—a charge Barnes denies. Lewis complains that Barnes and even Connally offered little help with the building’s mushrooming woes. “I’m angry at the way I was treated—like I was still carrying his luggage during the campaign,” says Lewis. The project’s loan with Bell Savings and Loan of California needed renegotiating, and Lewis took the opportunity to tell Connally and Barnes he was getting out. In December 1984 the two remaining owners of Shepherd Place, John Connally and Ben Barnes, signed a new loan agreement with Bell Savings, boosting their debt to $15.4 million. Lewis agreed to cover $750,000 of any losses on the project.

Shepherd Place opened with only two tenants. The office condominium concept had been shelved months earlier. Competing buildings were giving eighteen months’ free rent on a five-year lease; no tenant would lay out a cash down payment instead. Today a billboard outside Shepherd Place proclaims, “New Aggressive Leasing Program.” But callers are informed they cannot rent space in the building. The owners cannot afford the money to finish out new space. Eighty per cent of Shepherd Place remains empty.

In February 1985 Connally and Barnes began missing interest payments. Declaring the loan in default, the lender on August 22 demanded the full balance of more than $15 million. In October it posted the building for foreclosure. Once again Connally and Barnes turned to the courts to block repossession of one of their projects. They filed suit against Bell Savings and Lewis, claiming Lewis had conspired with the lender to let him out of a situation that was even worse than they had imagined. The suit won a court order blocking the sale, and the two sides resumed talking. Meanwhile, two years of property taxes—$85,000, including penalties and interest—remained unpaid.

In May 1986 Lewis filed for bankruptcy in Austin under chapter 7: liquidation. Lewis listed $1,063,833 in assets and $5,136,209 in debts. “The whole thing just went to hell,” says Lewis. “I grew too fast. In terms of growing too fast and being too big for your britches, I guess I learned at the feet of the masters.”

Ventured Capital

While real estate was the underpinning of their empire, Connally and Barnes invested in an assortment of other ventures. In those, their philosophy followed that of their development projects. They expanded aggressively, pioneered new concepts, did business with close friends and relatives, and poured money into personal passions.

• In 1982 Connally and Barnes decided to capitalize on the oil boom. Along with several partners, they created a company called Chapman Energy. By the time Chapman went public, the oil boom was over. Undaunted, they decided to expand anyway, using a new strategy. With Connally as master strategist, Chapman turned to buying up bankrupt energy properties on the theory that it was cheaper than drilling for reserves. Chapman’s assets soared from $3 million at the end of 1981 to nearly $82 million in 1985. But its earnings were puny. Chapman Energy made $177,245 in 1985.

• When Connally’s daughter, Sharon, who previously had run a shop in Barnes-Connally’s Floresville shopping center, decided to go into the Austin restaurant business, the two partners agreed to invest in Hill Country Barbecue. By the end of 1985, according to their personal financial statements, each man had a loss of almost $70,000.

• In 1985 Connally and Barnes, together with their deputy, Ralph Wayne, bought Lone Star Title Company. The agency, which handles the title work for almost all of their real estate transactions, bought an office condo in Barnes-Connally Center, the partners’ Austin headquarters. In May of this year the Internal Revenue Service filed a lien against the title company for overdue taxes of $58,666. Wayne says the taxes are being paid off.

• In 1983 Connally became chairman of Cable Advertising Systems, a public company that sells local advertising time on cable television networks. His son Mark is now chairman, and Connally and Barnes are directors. Cable’s revenues grew 70 per cent last year to $1.2 million. But its expenses grew faster, leading to a net loss of more than $2 million. Red ink didn’t keep Cable advertising from spending $566,000 in 1984 for an office condominium in Barnes-Connally Center. John Connally predicted the company would run in the black by year’s end, but Cable advertising lost $800,439 in the first half of 1986.

• Connally and Barnes are both directors and investors in American Physicians Service Group, which sells insurance and other services to doctors. The public company, which also bought space in Barnes-Connally’s building, quadrupled in size during the past four years by gobbling up other companies. It had been profitable for four years running, until last year. In 1985 the group lost $622,718.

Several other projects made money. Connally and Barnes made millions trading raw land in Austin. Barnes-Connally Center sold out. They made a modest profit on the sale of the Austin Business Journal. And after completing the dozen rental apartment projects they built with low-interest government bonds, they sold most of them for a profit.

But the profits from the successful deals couldn’t cover the debt from the far larger troubled ones. By 1985 their unsuccessful investments were rapidly consuming their capital—and changing their lives. Connally, preoccupied with his private business interests, severed two of his most prestigious affiliations.

In 1982 Connally had guaranteed a $4.05 million loan from First City Bank to former campaign aide Bryan Lewis, who had used the money to buy a River Oaks property. The property did not sell, the loan came due in February 1984, and Lewis could not pay it. First City foreclosed on all its collateral, but that proved woefully inadequate. Seeking payment of the deficiency, the bank then turned to Connally, a First City director since 1972. He refused to pay. On February 28, 1986, First City sued Lewis and Connally for the outstanding sum of $4 million. After the suit was disclosed, Connally declined to stand for reelection as a director. A bank spokesman denies the decision had anything to do with the loan.

In March 1985 Connally cut his ties with Vinson and Elkins. J. Evans Attwell, the firm’s managing partner, says it was mutually agreed that Connally had too many other business interests.

Barnes’s oldest business association, that with Herman Bennett, also took a bitter turn. Bennett believed his separation agreement had forever severed his fate from that of Barnes. After leaving Brownwood, Barnes had even formed a construction company of his own, BenTex, to replace the Herman Bennett Company. But in 1986 Barnes’s growing troubles brought the estranged partners together again. In April San Antonio Savings Association, declaring $19.5 million in loans on four Texas shopping centers in default, sued Barnes and Connally to collect on guaranties. San Antonio Savings sued Bennett as well, claiming he had also guaranteed the loans. Bennett responded by countersuing Barnes and Connally, as well as the lender, claiming they had deceived him about the terms on the loan and mismanaged the shopping centers.

Connally also showed signs of wanting to give tighter rein to Barnes’s management of their affairs. In 1984 Connally had arranged for his son Mark to join the partnership as a vice president. The move was widely interpreted within the firm as an attempt by Connally, who had left the business in Barnes’s hands, to take stock of where he stood. Mark left in 1985, but afterward John Connally became comanager of the partnership.

Even Connally’s increased attention could not stem the tide of problems. Suits from unpaid lenders and creditors stacked up. Banks posted more properties for foreclosure. Connally and Barnes continued to operate at a frenetic pace, but now it was not to build a fortune, but to stave off bankruptcy. In April 1986 the Bank of New England–Old Colony sued for payment of $4.1 million in loans and interest and posted the partnership’s headquarters for foreclosure. Barnes-Connally blocked the sale with a restraining order, then persuaded RepublicBank to take over the loan. In May Remington Savings Association, owed $1.4 million, foreclosed on a tract at Sixth and Lamar in Austin where Barnes-Connally had planned to build an office building. Barnes-Connally laid off fifteen of its fifty headquarters employees to cut costs. Many more debts—big and small —went unpaid. In good times, Connally and Barnes had left little margin for error. In bad times, their foremost asset was their powerful instinct for survival.

Buying Time

Can the Barnes-Connally Partnership survive? Because both men personally guaranteed nearly all their debt, the stakes are nothing less than their own personal fortunes. Connally and Barnes have thrown themselves into the task of solving their problems, and they insist they will never file for bankruptcy. “The governor and I do not want to be part of any company that goes into bankruptcy,” says Barnes. “We do not want to avoid paying anybody anything. We don’t want to have that on our record.”

They have tried unsnarling the tangled mess of their empire piece by piece, but it has been a difficult task. In August talks with Albuquerque Federal to take back Triple Crown in return for forgiveness of the debt collapsed, and the savings and loan filed suit to foreclose. Triple Crown’s owners named the lender as a defendant in its own action, claiming that Albuquerque Federal had reneged after committing to the deal. Triple Crown also retains the interest of the New Mexico attorney general, who says that Barnes, Connally, and Joe McDermott have failed to carry out the terms of the settlement agreement they signed: the $15,000 fine remains unpaid, and letters offering compensation have not been sent to those who had been promised gifts and vacations. Barnes says Albuquerque Federal was supposed to fulfill the agreement. Plans to convert Sunchase IV to time-sharing died after Manufacturers Hanover declined to fund the new strategy; Barnes says the bank has agreed to defer all interest payments on the project and wants Barnes-Connally to continue operating the Sunchase IV condos—even if they take two or three years to sell out. The lender on Shepherd Place in Houston, Bell Savings and Loan, in early September foreclosed on the property. Barnes says he and Connally have made an offer to buy back the building in return for being let off their loan guaranties. And the Estates of Barton Creek—Barnes’s most beloved project—is no longer under Barnes-Connally control. In late spring the chief lender, Community Investment Development Corporation, a subsidiary of a St. Louis savings and loan, assumed Barnes-Connally’s role as managing partner of the Estates.

Unable to find quick solutions to the problems of individual projects, Connally and Barnes have traveled far and wide in a quest to raise new capital by selling or refinancing assets. Barnes made one trip to Hong Kong, in pursuit of a deal with Lloyd’s of London. Both men also spent much time on a pair of deals that Barnes says will end the partnership’s crisis. The first would involve the sale of seven shopping centers and the partnership’s headquarters building for $88 million; after paying off the $72 million in debt on the projects, says Barnes, they would have $16 million in new capital. The second involves refinancing a tract of Travis County land, which Barnes says would free up another $7 million. Though nothing has been closed, Barnes is characteristically optimistic. “It’s going to put Barnes-Connally in a position to make all our lenders very happy,” says Barnes. “Everybody’s going to get paid.” All that they are doing has a single aim: buying time. Inevitably —and most fittingly—the fate of John Connally and Ben Barnes is wedded to that of their state. Only a major upturn in the price of Texas real estate can provide their long-term salvation.

“The real estate business is a cyclical business,” says Barnes. “A guy can look like a genius when it’s swinging up. When it’s swinging down, a guy looks like a fool. These times make people humble. I’d like to think I’ve been humble all my life. I’m pretty humble now.”

John Connally and Ben Barnes acknowledge they made mistakes. But ultimately they blame circumstances for their problems. “We were wrong, but it’s the first time in Texas’ history it’s been like this,” says Barnes. “If anybody’s to blame for our problems, it’s the economy, the banks, and oil.” He and Connally could as easily have been right. “Everybody’s got twenty-twenty hindsight,” Barnes says. “The people who don’t get criticized are those that remain in the stands. If you get down in the arena and get in the fight, you’re going to get bloody.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Business

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Austin