This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The car was a slightly battered dark green 1970 Oldsmobile 88, bearing Michigan plates and a couple of bumper stickers advertising rock ‘n’ roll radio stations in Detroit. Its back seat was piled high with plastic garbage bags and paper sacks that were stuffed with clothing; in the front seat were a big, rough-looking man, who was driving, and a small, thin woman with straight blonde hair and thick glasses.

It was one of the thousands of cars barreling along the Gulf Freeway from Galveston to Houston on a balmy Tuesday morning in the middle of May. From the air it would have been visible only as an insignificant speck; from the other side of the road, as a passing blur. It might have attracted a moment’s notice because it had obviously come from the North, but cars from the North are not so rare a sight in Houston these days.

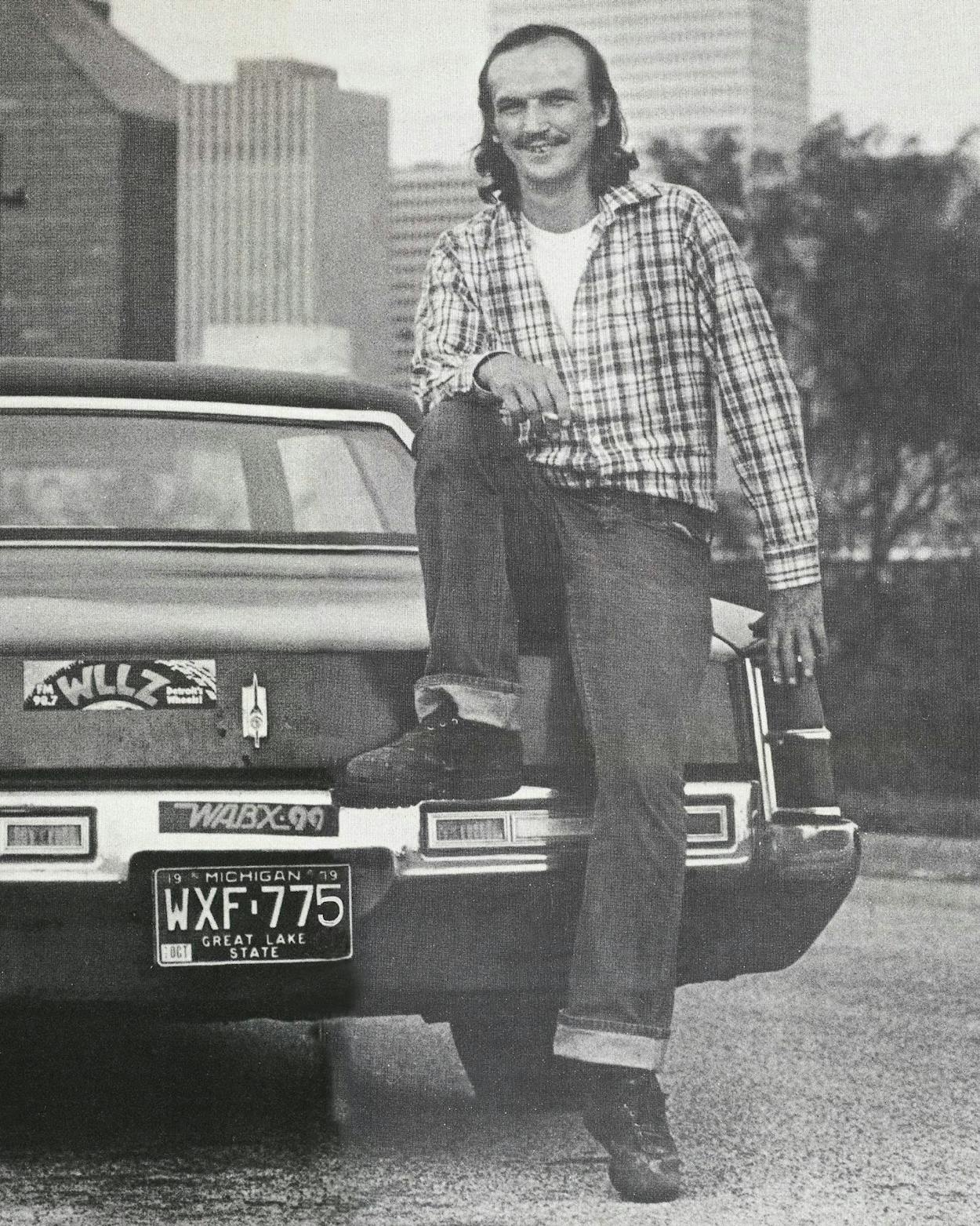

The man driving the green Oldsmobile was named Tom Lowell. He was 29 years old, with a thick brow that dominated his face and gave him a brooding look. He was wearing worn blue jeans and a white T-shirt. On each of his forearms he had a small tattoo, one of a peace symbol and one that said “Tom.” The woman with him was Debbie Lowell, also 29, the ex-wife of Tom’s older brother, Ray. She was a nervous, garrulous woman, impulsive where Tom was steady.

Tom and Debbie were at an extraordinary pass in their lives. Three days earlier, on Saturday, May 9, they had left Madison Heights, Michigan, a working-class suburb of Detroit, with the idea of starting all over again. They had weighed their lives in Detroit, found them irredeemable, and, at an age when most people are settling down, decided to move to a city they had never seen and where they knew no one. This Tuesday morning in May represented to them the end of everything that had gone before.

They had picked Houston as their destination because in Detroit, Houston has gotten the reputation of being the best place in the country to find a job. In that sense Debbie and Tom were part of another stream of people, one far less discernible than the inbound traffic to Houston that morning—the stream of unemployed people coming to Texas. In the thirties the movement that John Steinbeck made vivid in The Grapes of Wrath took 269,400 people out of Oklahoma along Route 66 (“the mother road, the road of flight,” Steinbeck called it). In the forties 258,000 blacks left Mississippi for the North, traveling by Greyhound and the Illinois Central to Chicago and beyond. Now at least as many people, maybe more, were leaving Detroit and the industrial Midwest, riding down IH 75, IH 40, IH 30, IH 45, looking for jobs—a huge and historic migration.

A hundred years ago, the phrase “gone to Texas” was so commonplace throughout the South that people would simply chalk the initials “G.T.T.” on their front door and take off, and everyone would know what had happened to them. The people who settled Texas were not the winners of the world; Texas was for people who had played their last card and come up short, people who were broke, people who were in trouble with the law. From the days of the Republic, Texas was the place where they could have one last chance. It was to the rest of the United States what America used to be to England. “When we want to say that it is all up with some fellow,” Thomas Hughes wrote in 1884 in a book called G.T.T., “we just say, ‘g.t.t.,’ as you’d say, ‘gone to the devil,’ or ‘gone to the dogs.’ ”

So it was with Tom and Debbie Lowell. For the past several months both of them had been on welfare in Detroit, scratching out an existence on $34.50 every two weeks from the State of Michigan, $70 a month in food stamps, and whatever they could beg or borrow from friends and family. They were poor, and also ashamed of themselves for being on the dole; Debbie, in fact, was getting far less welfare money than she could have, because she refused to put her children on the rolls. She had quit a good job as a machinist in a small factory in early 1979 in an effort to save her faltering marriage, but it hadn’t worked, and she couldn’t find a new job, either. Debbie had married at seventeen, and now, twelve years and three kids later, she was divorced, broke, on shaky terms with her family, and fed up with Detroit. Tom had been laid off from a job as a plumber in March 1980, and he hadn’t been able to find employment since then. The drinking, drugs, and brawling that had always been a counterpoint to his work had come to be the main feature of his life. As the months without a job went by, he could feel himself gradually slipping away.

Now, on this fine May morning, as high cumulus clouds rolled along overhead, as the palm trees and oleanders of the coast gave way to oil refineries, then suburbs, then finally to the vapory outlines of the Houston skyline, it seemed possible to Tom and Debbie that everything would change for them. Houston would embrace them, it would find them jobs, it would make life all right.

“Look, there it is,” said Tom, peering ahead and smiling slightly. “Houston!”

“Oh, wow,” said Debbie. She looked down and rummaged through her purse. “Let’s smoke a joint.”

Tom and Debbie had been thinking about Texas for some time before they finally moved. In 1978, during a cross-country journey to visit old Army buddies, Tom took a side trip to Galveston and worked on a shrimp boat for two days. But he got seasick and started home. In Mount Vernon he was stopped for speeding, arrested for possession of marijuana, and fined $300, but the notion of Texas that he took back with him was that it was a good place. Debbie, in the fall of 1978, had written off to the chambers of commerce in Houston, Dallas, and San Antonio for information, and in the summer of 1979 she and her husband got in their van and drove to Texas. Just past Dallas they ran out of gas, and when they found some, Ray, arguing that they could hardly move to a place where gasoline was sold only sporadically, insisted on turning back.

Debbie returned to Detroit in time to see the beginnings of the worst times the city had had in years. The auto manufacturers’ 1978 models had sold better than any previous year’s, but the terrible gas shortages and price increases in the summer of 1979, just before the ’80 models were to be introduced, had a catastrophic effect on the sales of cars—especially American cars, with their low gas mileage. In the fall of 1979 a series of layoffs began that left 140,000 American auto workers out of jobs. By this spring, Detroit was in the middle of the worst sales year since 1961, and unemployment in the Detroit area was 14.7 per cent. The mayor of Detroit estimated that 60 per cent of the city’s population was on some form of public assistance.

“From the days of the Republic, Texas was for people who had played their last card and come up short, people who were broke, people who were in trouble with the law. Texas was the place where they could have one last chance.”

Just as the price of gas crippled Detroit, it was a boon to Texas, and especially Houston. One third of the crude oil in the country comes from Texas, and the huge price increases of 1973 and 1979, along with the deregulation of crude oil prices by the federal government, brought the highest level of drilling activity in the history of the state, which in turn made itself felt throughout the oil business and Texas’ economy generally. Houston and Detroit are the two biggest one-industry towns in the country, built around the two biggest industries in the country. They were, in the late seventies, linked like two kids on a seesaw: every time oil prices rose it seemed to hurt Detroit and help Houston in exactly equal measures. Detroit’s population decreased from 1.5 million to 1.2 million in the seventies; Houston’s increased from 1.2 million to 1.5 million.

A generation ago, Detroit was the place to which unskilled labor was most attracted, because jobs were plentiful and paid well; and from the black counties of the South, from the mountains of Kentucky, from southern Canada, they came streaming in. Now Houston has become that place, on perhaps even a grander scale. Fewer people moved to Texas in the 1960s than in the 1870s, but during the 1970s, 1.7 million people came. They are not the wealthy or glamorous or successful, by and large. They are Mexican peasants, refugees from the terror in Southeast Asia, Nigerians, Haitians, Pakistanis, unemployed laborers from other parts of the United States. Detroit in particular has become obsessed with Texas. This spring the Houston Chronicle was selling 4200 papers in Michigan every Sunday. The Detroit television stations were full of reports, mostly debunking, about Texas, the new promised land. Twenty-one per cent of this year’s engineering graduates of Michigan State University took jobs in Michigan; 22 per cent took jobs in Texas.

Texas became a constant subject of conversation in Detroit. Everybody seemed to know somebody who was going there, or had been there, or was thinking of going. And conversely, Houston and Dallas became preoccupied with the invasion of Yankees, especially Detroiters. The letters to the editor columns of the papers were filled with arguments pro and con. A Houston radio station, KILT, proclaimed itself the official station for transplanted Detroiters. There were reports that jerry-built tent cities full of Midwesterners were springing up on the fringes of town. The Houston Chamber of Commerce announced that more than eight hundred people were moving to town every week.

Those who were moving from Michigan were coming to an entirely different kind of economy from what they were used to and a different way of thinking. Detroit is a union city, with high wages and relatively high salaries, a city where working for a large corporation is the dominant way of life and making good enough wages to buy a nice house is the dominant financial aspiration. Houston is a nonunion town, a place where wages and salaries start low and where complaints about that are not widespread because so much of the populace is dreaming of self-employment and, eventually, wealth. Houston’s dreams are entirely different from Detroit’s, and what’s more, they haven’t yet had the chance not to come true. Pay is low, but unemployment is extremely low. New ventures often work. People are in the mood to roll the dice.

But for people in Detroit, it’s difficult to accept this new structure of aspirations, especially when there will be a financial sacrifice in the short run. So those who are moving are the ones without money coming in: the middle-class white-collar people laid off by the auto companies and the thousands of smaller businesses that the auto companies support, and the people at the bottom of the blue-collar world, who never made it into a union and earned only $5 or $7 an hour even when they were working. They have 39 weeks of unemployment benefits, and then it’s leave or go on welfare. But laid-off auto-assembly-line workers, thanks to an awesomely misguided federal program called Trade Adjustment Assistance, can make as much as 70 per cent of their old weekly wages, tax free, for two years and thirteen weeks (under President Reagan’s budget cuts, this length of time will remain the same); at the moment, many of them are doing better by not working in Michigan than they would by working in Texas. So most of them stay put, whiling away the time, some of them driving down to Texas, sniffing the air, and returning, waiting for the money to run out. Toward the end of this year, for many of them, the end of the benefits will finally come, and then the migration will increase. For now, it is left to people like Tom and Debbie Lowell to blaze the trail.

“Houston and Detroit, in the late seventies, were like two kids on a seesaw: every time oil prices went up, it seemed to hurt Detroit and help Houston in exactly equal measures.”

Detroit for Tom and Debbie meant a triangular territory about eight miles on a side, bounded by Fourteen Mile Road on the north, the Walter P. Chrysler Freeway on the west, and the Edsel Ford Freeway on the south and east. The triangle contains the east side of Detroit and a handful of industrial towns—Hamtramck, Hazel Park, Madison Heights, Warren, Center Line, East Detroit, Roseville—and Tom and Debbie rarely ventured outside it. They had never been to the Renaissance Center in downtown Detroit, or the Ford River Rouge plant in Dearborn, or most of the other landmarks of the city. They thought of anything to the west as an impenetrable black ghetto and anything to the north or east as inhabited only by millionaires.

Debbie’s grandfather, Joseph Zaverl, came to the triangle in the forties, just when it was becoming a workingman’s paradise, a no-nonsense region of factories and bungalows and bars and restaurants and shops and factories that, because it offered the promise of high wages and single-family home ownership, was a magnet for people from all over the country. Debbie’s grandfather had been a coal miner in Cannonsburg, Pennsylvania; her father was from Canada and met her mother in Detroit.

Her parents were divorced when she was only a year old, and her mother got a job in a bakery and moved Debbie and her two brothers in with the Zaverls. They lived on the far east side of Detroit. Tom’s family lived in Madison Heights, at the other end of the triangle. His father worked at a Chrysler stamping plant in Warren, and when Tom was thirteen his parents were divorced and his mother moved to Tonawanda, New York, leaving Tom and his four brothers and two sisters under extremely loose supervision. Tom dropped out of high school when he was sixteen, went to work, joined the Army when he was twenty, got married, got divorced after a month, got a high school diploma in the service, and came back to Detroit in 1974 and began working at a series of low-paying jobs. Debbie dropped out of high school in her junior year, when Detroit began a busing program. Her mother dated Tom’s father for a time, and she got to know the Lowells that way. She married Ray in 1969.

As time went on, it became clear that Debbie and Tom’s friends were not going to lead lives as good as their parents’. Some of them got into the union and went to work in the auto plants, but being the least senior people there, they were often laid off. A great many of them fought in Viet Nam, and that set back their careers. They became mechanics or plumbers or truck drivers (like Ray) or waitresses. If they got married, they often got divorced too. They lived with their parents well into their late twenties. Jobs kept getting scarcer, but they stayed in Detroit because they had been raised to stay. This spring the greatest factory in the triangle, Chrysler’s Dodge Main plant in Hamtramck, was torn down, and everybody was talking about Texas, but still they stayed.

On June 24, 1980, Debbie moved out on her husband for good, and when her efforts to find a job were unsuccessful her thoughts began to turn to Texas again. Her children were at Ray’s house, and Ray didn’t like Debbie coming to visit them because his new girlfriend wouldn’t come over when Debbie was there. She didn’t feel at home at her own family’s house, either, because she didn’t get along with her grandfather. She had no money to get a place of her own. Tom was in the same situation, living with his brothers and feeling a growing need to impose discipline on himself.

Debbie and Tom had known each other for years, and although Debbie and Ray’s divorce had created bad feelings between them, in the spring of this year they began to sound each other out about moving to Texas together. Unlike all their friends, they were actually willing to pick up stakes and leave Detroit. Debbie had a car and a $600 income tax refund that Ray had given her on the condition that she quit coming around to his house. Tom was tough and strong and likely to have an immediately easier time in Texas, in the way that men always do on an economic frontier. The two of them could protect each other against being lonely. They would be better off together than apart. They could forget their differences and enjoy being together, without taking on the burden of needing each other.

They stayed in Detroit through the end of Debbie’s bowling season, in mid-April, and then through a concert by the rock group Styx on April 30 that Debbie especially wanted to see. Debbie would have liked to stay even longer, for a friend’s wedding on May 29, but Tom said if they didn’t leave before that they’d end up spending the whole summer in Detroit. He promised to send Debbie back for the wedding with the first money he made. On Wednesday, May 6, Debbie told her mother she was leaving; on Friday night, May 8, she broke the news to her boyfriend, Robert Zaletskis, a gas station mechanic and bar bouncer known to his friends as Mad Dog; and the next day she and Tom left. They spent the night at a motel on IH 75, just north of the Kentucky-Tennessee line. The next day, Sunday, it rained and one of their tires blew out, but they pressed on, and at nine-thirty in the evening they entered the state of Texas. They slept in the car in a rest area outside Dallas, and on Monday morning they hit a traffic jam near Houston and decided to skirt the city and go to Galveston instead, for a day of rest. They spent the night at the Islander Beach Motel, checked out early, and began the last leg of the trip, the short drive into the city on the Gulf Freeway. Their theme song for life in Texas, they decided, would be a tune popular on the radio just then, called “Just the Two of Us.”

Houston beckoned, vaguely. Having come there at last, Tom and Debbie had no idea what was supposed to happen next or how, exactly, the city would choose to bestow its bounty upon them. On the way in they had passed some apartment complexes north of town that looked nice, and because those were their only specific points of reference, they headed for them. Tom stayed on the highway past downtown, driving carefully in the middle lane while the hot cars of Houston, pickup trucks at one end of the scale and Lincolns at the other, dodged in and out of the flow of traffic at breakneck speed. He got off at Parker Road, turned around, and headed south on the North Freeway access road, stopping at a two-story building of faded white brick with a sign out front that said “Skylane Apartments North—Linen Dishes Etc.” The office door was locked, but resolute knocking produced a middle-aged woman with lacquered hair, who opened the door to reveal a murky apartment lit only by a color television set. For some reason, she was wearing extra-dark sunglasses. She said a two-bedroom apartment would cost $150 a week, plus a $100 deposit. “Gee whiz,” said Debbie, after they had said no, thank you, and left, “they think we’re made of money.”

The next apartment complex down the road was called the Villa Provincial and was overseen by a languid young man with neatly parted red hair and a ruffled sport shirt, whom Tom and Debbie found in an office filled with hot rod magazines. He showed them an immaculate unfurnished apartment for only $288 a month, but he said it was the policy of the Villa Provincial to rent apartments only to people with jobs. He could check their credit, but that would take three or four days. “Thanks, hon,” he called after Debbie as she was on her way out. “Good luck to ya.”

They got in the car again and drove back toward the city, with no plan in mind. Tom got off at an exit marked downtown, because that seemed like the logical place to go, and found himself right in front of the city hall. He parked, got out, and bought a Chronicle. He and Debbie blinked in the bright sunlight and looked around them. It was lunchtime; the streets were filled with men in suits walking in twos and threes, neat-as-a-pin secretaries, young hustlers with big plans, courtly lawyers of the old school. A man walking by said to his companion, “Y’know, a lot of people are leaving Detroit and coming to Houston.” Debbie stared at the man, amazed. “God, Tommy, y’hear that?” she whispered. “We just left Detroit.”

Tom and Debbie wandered into city hall and asked the information clerk whom they should talk to about finding a job in Houston. The clerk said to ask at City Services Information, and a young man there told them they ought to go to the Greater Houston Convention and Visitors Council a few blocks away. There, the young woman behind the desk gave them a guide to hotels and motels in the area and told them to go to the Texas Employment Commission, which she said was at 612 Austin Street. “Y’all want to sign the register?” she asked them as they left. “Y’all want a restaurant guide?” It turned out, after a walk, that there was no such address as 612 Austin Street. Tom went into a life insurance office and asked the receptionist where the Texas Employment Commission was. She said she would be glad to help, having arrived in Houston from Michigan herself only six weeks earlier. She looked up the address in the phone book; it was 2613 Austin. They walked back to the car and consulted their Road Atlas, then drove to a plain building south of downtown. Inside was a large waiting room that was filled with six-sided tables at which a couple of dozen people were sitting patiently. The clerk told Tom and Debbie it would be a three-hour wait before a job specialist could see them. They decided to come back in the morning.

In the car Debbie flipped through her hotel brochure, looking at prices. “Memorial Park Motel,” she said presently. “One-thirty-three-fifty a week and fifty deposit. That’s not too bad.”

“A week?” said Tom.

“Between the two of us.”

Tom got out a pencil and scratched down some numbers. “That’s five-thirty-four a month.”

“Where you gonna get off that cheap in a month?” said Debbie.

“At that place we was in this morning.”

“That’s two-eighty-eight,” said Debbie. “But that’s no TV, no phone, no nothing. You gonna come home at night and sleep on the floor?”

The Memorial Park Motel is, in strict truth, nowhere near Memorial Park. It is near Allen Park, on Waugh, but even that does not make it a cheery place. It is a large concrete block of a building, with long, windowless corridors lined with dirty orange shag carpet. Its most affluent patrons are the third-echelon businessmen who come in at lunchtime, leaving younger women fixing their makeup in the passenger seats of their cars, ask if there is a day rate, and leave when they are told there isn’t one. The desk clerk there, a pleasant middle-aged lady, showed Tom and Debbie room 434, which was impossibly dingy and looked out on a garbage-strewn alley, and then room 427A, which was just a touch nicer in that it had bigger beds and looked out on an asphalt roof.

“What do you think, my man?” said Debbie. “It’s got bigger beds, huh?” “Yeah,” said Tom. “Guess so.”

They walked back downstairs, and Debbie paid the clerk $317 for the deposit and two weeks’ rent.

“Y’all just get here?” the clerk said. “Lord, I know what you’re going through. ’Cause I been with no job or nothing.”

“That’s where we are right now,” said Debbie.

“What kind of work you looking for?” said the clerk.

“Anything,” said Tom. “Don’t care what it is, long’s it’s work.”

There was an awkward pause. “You got free movies in your room,” the clerk finally said, helpfully. “You got X-rated and you got regular.”

“Thanks,” said Debbie.

In the room, which smelled of tobacco and stale air, Debbie and Tom began rifling through the Chronicle help wanted ads—there were nineteen pages of them that day and, by the way, eight in the Detroit Free Press—and making phone calls. Tom made an appointment to interview for a job as a forklift operator the next morning, and Debbie made an appointment to see about the job of security guard in a new factory; she had once worked as a security guard in Detroit, and it had been her favorite job. They went out for a hamburger, talked about what kinds of cars they’d buy when they got rich, watched a movie on television, and went to sleep.

After only a day, and barely consciously, they had made certain decisions that would govern the next period of their lives. Completely by chance, they had decided to live in the tough slice of town between White Oak and Buffalo bayous, where drab, truck-stop-lined Washington Avenue is the main thoroughfare, where downtown is visible on the horizon and River Oaks, a short distance to the southwest, is somehow a felt presence, where the endless suburbs seem far removed. As far as work went, their two sources of job information, the general help section of the want ads and the employment commission, were inevitably going to lead them away from the oil business, where Tom might well have ended up a roughneck, and toward the other great boom industry of Houston, which is growth itself. They were going to encounter a brand-new economy made up mostly of small, quick-buck industries that were springing up all over the place to serve the needs of the thousands of people moving to town and, in so doing, to hire many of them too.

The next morning there was no hot water, and Debbie found a roach in the sink while she was washing her hair. Tom killed it. Debbie called her sons in Detroit. They asked her when they would see her again, and she said she didn’t know.

At seven-thirty they took off out Katy Freeway, heading west. At an exit that seemed to be past the place where Houston finally ends, they turned north, drove through a marsh on a rutted country road, and soon, lo and behold, a brand-new factory, enclosed in a ten-foot wire fence and surrounded by empty fields, rose up before them. The sign outside said “Toshiba International Corp.” In the parking lot Debbie spotted half a dozen cars with Michigan plates. She went inside for an interview and came out looking crestfallen. They would call her and let her know.

Now they drove east to the place where Tom had his appointment, a warehouse so new that it didn’t have an identifying sign on it. “So,” the man in charge of hiring told Tom, “you’ve decided to come down to the land of opportunity, huh?”

“Yeah,” said Tom. “Plus, it’s nice all year round.”

“That snow’s bad stuff,” the man said. He told Tom he’d get back to him.

Tom and Debbie decided it was time to return to the Texas Employment Commission. They filled out their applications and waited glumly at a table, leafing through the want ads. From time to time one of them went out to the pay phone in the lobby and called a potential employer, but everybody insisted that they come out and interview in person. Tom drew a picture on a scrap of paper of a young man smoking a joint. Debbie went outside to look at the car and found that it was slowly leaking transmission fluid. Tom took off his T-shirt and crawled underneath it to look. He came back inside. They waited some more.

“Shit,” said Debbie, “this is longer than Michigan.”

“You gotta wait sometime in your life,” said Tom.

“I wish I could walk in and get a job today. That would top my day.” Debbie was unraveling a bit. She hated for her life to be an unresolved proposition—that was one reason she had left Detroit—and that very quality in her, oddly, kept her life unresolved. She wanted things to work out quickly, and when they didn’t she wanted to try something else.

Tom glanced at the want ads. “You could be a nude dancer.”

“Oh, sure,” said Debbie. “Get up there on that stage. I’d never do that.”

“Says it right here. Foxy girls. Five hundred a week.”

“I bet you don’t even really get that,” said Debbie.

At one-thirty in the afternoon a man in a tie finally called their names. They went into small cubicles for interviews meant to determine their skills, and then into another set of cubicles for a second set of interviews that would match them to specific job possibilities. Tom came back first, holding a piece of paper with the names of two companies on it. Then Debbie came back, on the verge of tears.

“Wouldn’t you know?” she said bitterly. “He gives me one job, and it’s a security sergeant, not a security guard. I’m not gonna get that.”

“You wanna check it out anyway?” Tom said tentatively.

“We better go home and fix the car. No f—in’ job, no money, no car. Tommy, I tell you, I am so f—in’ pissed off I’m about to go over there to the 7-Eleven and put in an application.”

Back at the motel, Debbie ran up to the room, tears in her eyes, and Tom settled down to work on the car and wait out the storm. When he went inside, Debbie had regained her composure. She had put a photograph of her children up in the room, and a small plastic statue that bore the legend “World’s Best Mom.” She was sitting with the want ads spread out before her, furiously marking them up with a pencil. Tom called the first of the two employers the Texas Employment Commission had listed for him. The man who answered said the job was already filled. Tom sighed and turned on the news. The Pope had been shot.

“I got two in the Galleria, Tom,” said Debbie, trying to cheer him up. “And look at this, they still got mud wrestling. Thirty dollars for thirty minutes. What we’re gonna do tonight, Tom, is go through and make a list.” Her eye fell on a tiny ad that read “NEED EXTRA MONEY? Earn $6 per hr. + bonus & comm. Become a C & W dance instructor. No exper. necessary. 270-0245.” She called the number, spoke for a moment, and then called out, “Found another one, Tommy!”

“What?”

“I might be a C and W dance instructor. You know what that is?”

“What?”

“Country and western. She told me to be there at four o’clock tomorrow. I never done it, but it sounds okay.”

Tom telephoned his last lead from the Texas Employment Commission, a place called Class A Maintenance. “My name’s Thomas Lowell,” he said. “Calling about that Class A Maintenance.”

Debbie looked at him expectantly; Tom turned his back and hunched over the phone in fierce concentration. “I got about five, six years experience. I worked for a plumbing company. See, I just come down from Michigan. I worked for a grease-trap place up there. I started at four, got up to five-fifty, but I’d be willing to start at four-fifty if I have to.” Without thinking about it, Tom had offered to make the economic bargain required in moving from Michigan to Texas: working for less money.

He listened again. “Yeah, hey, I’m willing to work, y’know. Yeah. I’d be willing to work as long as you want me to and start when you want me to.” The man at Class A said something else. “Yes, I do, but I’m willing to get it cut. I’ll get it cut if you want me to. My hair ain’t that long, really. It’s just over my ears a bit. Yeah, the ones with the ponytails, I understand.”

Tom covered the mouthpiece of the phone with his hand and whispered to Debbie, “Guy’s gonna start me at five an hour. Since I ain’t got no tools. Says he don’t like to start ’em high.”

He uncovered the mouthpiece again. “I can start tomorrow morning if you want me to. Like, I’m willing to start right away. You just tell me right where you’re located at, and I’ll be right there. ’Cause I come down here with very little money and I got to get work.”

Tom hung up and allowed himself a huge gap-toothed grin. “Ten o’clock tomorrow morning, I start,” he told Debbie. “I’m gonna learn air conditioning!”

“You and your f—in’ luck,” said Debbie. “I shoulda been a mechanic or joined the f—in’ service. Now can we f—in’ go eat?” Tom stared back uncomprehendingly, and Debbie’s features softened. “Well, that’s great, Tommy,” she said. “Now we gotta get me lined up.”

In the morning Debbie dropped Tom off at the Class A Maintenance office, a weathered ranch-style tract home in a nondescript industrial neighborhood northwest of town, and once again set about the work of finding a job.

She drove back to the motel and called the Toshiba International Corporation about the security guard job. It had been filled. She picked up her marked-up copy of the want ads and left again, bound for places that were at an astonishing distance from one another and also astonishingly new. They gave rise to the sense that the way to find work in Houston was to get to the breaking crest of the wave, the very latest place to have been reached by the growth, where Houstonians were starting businesses out of thin air and immigrants like Debbie were arriving at exactly the moment of conception to staff them and to be their customers.

Debbie drove out to a day care center in a half-finished shopping center on Dairy-Ashford Road fifteen miles from downtown and right at the western edge of the city limits, with only the empty grassy coastal prairie stretching before it and only subdivisions and franchise outlets to the rear. Inexplicably, the day care center was teeming with kids. She filed an application and then drove to the office of Mustang Security Services, a bungalow on a quiet street in Montrose with a huge plastic rearing horse mounted on its roof. She went to another security service far north of town on North Freeway. She went to Smith Protective Services on Westpark, which stood out even among security companies for its precise spiritual kinship to a police precinct headquarters. She went to the Galleria, gaping at the splendor of Neiman’s, the skating rink, and the boutiques, and applied for a guard’s job at the glossy offices of Gerald D. Hines Interests. She bought a postcard to send to Mad Dog that read “Love Is Big in Texas.”

She perceived a city that was at once seedy and rich and thus offered her both a toehold in her present station and something to which to aspire. It was warm and it was new and she liked it. But there was a way in which Houston played to her weaknesses, though she barely realized it. She was an insecure person who craved security, a home, and a sense of belonging; Houston is nervous. She could be moved away from the steady progress toward her goals that she needed by distractions and inconveniences that would make her take her eye off the ball; Houston offered many of them.

Debbie left an application at a Shell station at the corner of Westheimer and the Loop. She went to a place called A&B Security on the fringes of downtown and left an application there, too, with a stern, aging receptionist who presided over two bare rooms and a coffee machine. “I will be sure that Captain Betancourt sees this,” the receptionist told her, with great formality. She went back to the motel, smoked a joint, called the day care center, and was told she had a job, at $4 an hour, starting the next morning. Things were going well.

She left again and went to the country-and-western place, which was in a small strip shopping center in Sharpstown. It had a temporary sign outside that said “Dance Lessons—Exclusive Private Club.” Next door on one side was a bar; on the other side, a guns and ammo store. Inside, an elegant Mexican American man with perfectly graying temples and a ruffled shirt worn with a vest spoke briefly with Debbie and told her to come back at six. She rushed out, bought a curling iron at Walgreen’s, went home, changed, fixed her hair, put on perfume, and headed back to Sharpstown to learn the science of country-and-western dancing. She would have to go through two weeks of instruction, but after that, the man had told her, she would be ready to teach. After less than a month in Houston, then, if all went well, she would be a semiofficial purveyor of Texas folk customs to suburban Texans who had never known them but somehow felt the need to.

At the dance hall, a boy in blue jeans and cowboy boots was waiting for her. “Hi,” he said. “I’m Rafael. And we’re gon’ have a good time.”

From that moment forward, Debbie’s life in Houston went quickly downhill. First, she left the country-and-western place early because as soon as the lesson began she came to the immediate and dramatic realization that she didn’t like country music, that she couldn’t keep the beat, and that her loyalties lay with rock ’n’ roll. That was one job down the drain. That night as she was watching television, a roach walked across her shoulder. She screamed, got dressed, and told Tom she was going to sleep in the car. He promised her they would move out. The next morning, Tom insisted on taking the car to his job, so Debbie didn’t go to the day care center. She was feeling hopeless and so didn’t take the trouble to find out about taking a bus there—it was sure to be an endless trip anyway—or even to call and stall for time. So her second job slipped through her fingers too.

The next day, Saturday, Tom and Debbie went by an apartment complex called the Caribe, just up the street, where Tom had done some maintenance work that week, and picked out a clean one-bedroom second-story apartment with nearly white walls, a reddish-brown shag carpet, and three or four old pieces of furniture. The could move in on Monday if they brought $227.92 for the deposit and the first two weeks’ rent to the manager by six o’clock. Unfortunately, they had spent almost all of their money, and Tom wouldn’t be paid until the end of the week. They had to find some cash.

On Monday Tom borrowed $50 from his boss, and Debbie asked the clerk at the Memorial Park Motel to refund their deposit and the second week’s rent they had already paid. He gave her the deposit—that was $50—but said the rent was not refundable. So when Tom came home he had a talk with the desk clerk. He leaned forward menacingly, grabbed the bill out of the clerk’s hand, and told him he would be in his room waiting for the $133.50. Five minutes later, the clerk appeared with the money, and Tom and Debbie hurriedly loaded up the car, drove to the Caribe, and paid their rent at exactly six. They bought $30 worth of groceries, set aside four quarters for phone calls, and spent every remaining cent of their money on a big dinner at a fast food place called Taco Inn. Debbie was overjoyed to find that they had tacos in Texas too.

Now Debbie and Tom began a week of total penury while they waited for payday. Had they been as broke in Detroit, they could have bummed food and money from their friends and relatives. That they couldn’t do so in Houston was the greatest sacrifice their pioneering had brought them. They were, as almost nobody in America is anymore, hungry. Each day they had a glass of orange juice for breakfast, nothing for lunch, and one real meal at dinner. They ate frozen chicken pot pies on Tuesday, frozen spaghetti with meat sauce on Wednesday, frozen Salisbury steak on Thursday, and on Friday they were left with a can of Diet Pepsi and half a box of Cheerios.

While Tom worked, Debbie hooked a throw rug with Fred Flintstone’s picture on it and did the desultory job hunting that was possible without a car, turning up nothing. Around the Caribe’s pool, which smelled faintly of the residue of a break in the sewer system the week before, she met some of the other tenants: a girl called Natalie, a guy called Rabbit, a guy called Bro, and their next-door neighbors, two guys called Rick and Alabama. Rick and Alabama had a stereo, a color television, and dope, which was nice, but both of them had just gotten out of prison—for armed robbery and attempted murder, respectively—and Alabama, in particular, seemed not to have emerged unimpaired. He was a thin, pale, walleyed man in his late thirties with curly hair and flashy clothes and a way of looking behind him a lot, and he told Debbie she couldn’t imagine how long he’d been without a woman.

The wedding that Debbie was supposed to go back to Detroit for was still ten days away, but the idea began to take hold in her mind that she would return a little early. It was as if she had somehow lost the momentum that seemed to be so crucial in Houston; if she went back now, she could round up Tom’s stereo and a few other odds and ends that they needed anyway and come back fresh after the wedding. She had even heard around the Caribe that there would be an assistant manager’s job opening up there about that time, because the current assistant manager had been assaulted in the complex a few weeks earlier and might not be able to resume her duties. And it would be nice to be away from that creepy Alabama for a while. Debbie made reservations to leave on Friday night, May 22, ten days after their first day in Houston, on a 2:40 a.m. flight, and to return on Sunday, May 31.

Tom came home early from work on Friday, and at six he and Debbie drove out to his office to pick up his pay. Tom’s boss, Joe Jones, a wiry, hell-for-leather little man who was 42 but looked older, motioned him into a chair and did some figuring with a pencil stub on the back of an envelope. “Let’s see,” he said, “I got you down for forty-two hours, and at five an hour, that’s two-ten. Now, taxes, let’s figure that at twenty per cent, that makes it one-sixty-eight.” No doubt Joe did his paperwork and form filing at some other time. “You owe me fifty from the other day, I owe you six from last week, make it forty-four. That’s one-twenty-four.” He pulled out his wallet and counted out the money. “Boy, you made more money this week than I did,” he said with a grin. “Mama keeps everything I make ’cept fifty dollars.”

Tom folded the money neatly and put it in his pocket. It was the first he had earned in a year and two months.

Joe walked Tom and Debbie back to their car and bade them a fond good-bye. “Hey, guess what I’m doing this weekend?” he said as they were starting the engine. “I got a couple of friends who’re narcotics agents, and I’m going with ’em on a bust.” Involuntary looks of shock crossed Tom’s and Debbie’s faces. “Hey,” said Joe, reassuringly, “it’s just the big guys they care about. Y’know, the ones that’ll get their name in the paper.”

The money, of course, was not enough to pay for Debbie’s plane ticket; it was barely enough to support Tom for a week, and he had a month’s rent due in another week as well. They stopped at a pay phone on the way home, and Debbie called Tom’s brother Kenny in Detroit and wheedled and cajoled him into driving out to the airport and buying the ticket there. Then they got a hamburger, drove home, and dropped in on Alabama and Rick for a few hours until it was time to go to the airport. Rick told prison stories. Alabama paced around the apartment, disagreeing vehemently with anything anybody said. Tom told Debbie to be sure to bring back from Detroit his rug with John F. Kennedy’s picture on it. He said he had a special fondness for JFK because on the day he was assassinated, Tom, then twelve years old and quite unruly, was in juvenile court on charges of having started a fire in a garage, and just before he was to be sentenced the news came over the radio and the judge dismissed all the cases.

They drove to the airport two hours before the flight was to leave, and Tom waited loyally, not talking much, until it began to board. He had a disconsolate air about him.

“Guess you’re gonna leave your pajamas here,” he said at last.

“Yeah,” said Debbie. “I don’t need ’em.”

“What about when I have wild women over and they see your pajamas here? What are they gonna think?”

“They can think what they want to, Tommy.” Debbie leaned forward and kissed him. “I will be here Sunday night,” she said, and turned to go. “I will return.”

Five days later, on Wednesday, May 27, Debbie’s grandmother suffered a massive heart attack in the parking lot of Doslea’s bingo hall in Roseville, Michigan—a cavernous, intense place where she and Debbie’s mother went two or three nights a week—and died in her car. At her mother’s fervent urging, Debbie decided she had to stay with her family, and she put off her return to Houston for a while.

Shortly after Debbie left, Tom arranged to buy from Joe Jones a beat-up old green pickup truck, to be paid for through weekly deductions from his pay. Debbie’s Oldsmobile was not the ideal car for a maintenance man, and Tom found that he never drove it anymore. So he really no longer needed Debbie. Her money had been spent, her car rendered useless to him; he had a job; she was gone. And yet he felt her absence from his life more and more keenly. It began to seem to him an important final test of his life in Texas that she come back, to give his life companionship and some greater degree of order than he could muster by himself.

Although that nagged at him, Tom was settling into a routine at work that he was beginning to find quite congenial. At nine every morning he would drive out to Class A Maintenance and wait for the arrival of its motley work force: Joe Jones; his wife, Rita; his 75-year-old father; his 15-year-old nephew, James Falke, who was from Fort Worth but had recently left home in the wake of a dispute with his parents; and occasionally a man named Daniel Ramirez, who worked mostly at the River Oaks Country Club but helped out at Class A on the side. Joe would give Tom a list of jobs, and Tom and James would take off in the truck to clean out sewers, hang doors, and replace air conditioning units at apartments all over Houston.

Joe Jones had started Class A on June 9, 1980, and he often told Tom that it was going to make him a millionaire. He said Tom most likely would do extremely well at Class A himself, because it was a growing company and he was in on the ground floor. Joe was born in Freeport and raised in Houston, and he got into the maintenance business as a teenager. He and Rita got their air conditioning repair certificates in 1978, and he soon thereafter left his job as a maintenance man in the apartment complex empire of Harold Farb, became a self-employed air conditioning repairman, and then founded his own company. His most recent venture was the Class A School of Air Conditioner Repair, in which Tom and James and three other young men made up the first class. Every Monday and Thursday night Tom went to class, which was held in the garage of the house that served as Class A’s office, and after two months he would be certified as an air conditioner repairman. That was where the real money was in Houston, Joe said.

In fact, Joe had a deep and abiding faith in the window air conditioning unit and the city of Houston as engines of prosperity. His faith had an overwhelming air of the unlikely about it—Joe himself, gnarled and toothless and dressed in work clothes, did not look like a millionaire-to-be, and the office, which had no sign outside and was strewn inside and out with an awesome array of out-of-repair window units, did not look like the beating heart of a business empire. It was in some ways exactly analogous to the kinds of small, second-tier enterprises that Tom used to work for in Detroit; its fortunes were tied to whether people kept moving to town, whether apartment complexes kept being built to house them, and whether there was enough money around to pay for the kind of maintenance work that people in Detroit have by now largely decided to let slide. But Houston was meeting all those conditions for the moment, and as a result it was fostering the kind of attitude that Joe had and that was beginning to infect Tom. He was working very hard, six or seven days a week, for not very much money, but he liked to work and felt that as time went on Houston would reward him far more richly than it was doing now, and far more than Detroit could. He had no proof of it. He led a rough and shabby life on the lower fringe of the working class. But that was how he felt.

In the meantime, it was becoming clear that Tom wouldn’t be able to pay his June rent at the Caribe when it came due. On Sunday, May 31, he went to see the manager to plead for more time, and she told him to give her everything he had—a little more than $100—and to be sure to have the rest in a week.

On Wednesday, June 3, he called Debbie in Detroit. “I can’t eat or nothing,” he told her. “I didn’t do my laundry or nothing. I had a bad scene with the landlady on Sunday. She took every penny I had. And I gave her my word I’d have the rest. Can you get me any money up there?”

“I can try,” said Debbie. She sounded reluctant.

“What are you doing up there?” said Tom. “You still waiting for that wedding?”

“No,” said Debbie. “I’m planning my own.”

“What?”

“With Mad Dog. At the end of June.”

“Then you won’t be coming back here.” Tom didn’t say anything for a moment. “Debbie, I told you I’d marry you anytime.”

“I want to come back there, Tommy,” Debbie said, studiously not rising to the bait. “It’s just that Mad Dog don’t want to.”

“I can hardly hear you,” said Tom.

“I know. It’s so hard. It’s like you’re a million miles away.”

Debbie didn’t send the money. But Joe Jones told Tom that he and James could live in the Class A Maintenance office rent free if they would pay the bills and take the night calls, and Tom gratefully accepted. On Saturday, June 6, he cleaned out his apartment at the Caribe and moved in. He rented a color television set for $15 a week and bought a three-piece bedroom set secondhand for $100.

He and James fixed the place up. They painted the walls and installed two window units, and by the time they were through it looked all right. The living quarters were comfortable, even homey. James was an okay kid, though certainly not all Tom wanted in terms of companionship. Tom parked Debbie’s car across the street, kept working, and waited to see what would happen.

On June 26 the mail brought a nine-page letter from Debbie, written in an exuberant schoolgirl’s script on notebook paper.

“Hi, Tommie,” the letter began.

“Well here I am writing you the letter I promise you. So how are you. Find I hope! As you probably know things back home here arent know different then they were when I left. One thing good that happen since I’ve been back is I got a proposal from Mad Dog.”

She went on with a few details of her life, then got to the heart of the matter:

“I don’t want to stay here. There’s nothing I can do to change my feelings about living here.

“So Tommie please help me out.

“Please write me back & help me out by giving your opinion on what I should do.

“Just remember I want to come back down there. I just can’t make it here.

“Remember when we left I told you I could’ve changed my mind that night before we left & turn around & went back & stay’d with Mad Dog & I didn’t I left because I knew where I wanted to live. And that place is

“HUSTON, TEXAS.”

Tom didn’t answer the letter. A few days later, a second letter arrived. Debbie said she still badly wanted to come back to Houston, and she asked Tom to send her the money for a plane ticket. She didn’t mention Mad Dog at all.

Providentially, just then Joe and James had a fight that ended with James’s going back to Fort Worth to try his luck with his parents again. Tom asked Joe if Debbie could come down and stay in James’s room at Class A. Joe said that would be fine. He said he was glad to do Tom a favor, and he probably could even use Debbie in the business; he was beginning to need a receptionist. Now Tom’s only problem was scraping together the money for Debbie’s ticket.

On July 7, Tom called Debbie at her mother’s house in Detroit, but her mother said she was at Ray’s visiting the kids, so he called her there. “Debbie,” he said, “I don’t have the money yet. Why’ncha ask Kenny if you can borrow it off of him?”

“I don’t know,” said Debbie.

“Why’ncha ask him? Tell him I’ll send it back to him this month.”

“Hang on and I’ll call Ray.”

In a moment Ray came on the extension. “Hey, Tom,” he said.

“What?”

“Hey, I got four checks here for you. Oakland County Department of Public Services. Thirty-four-fifty each. What do you want me to do?”

“Debbie,” said Tom, excited, “them checks right there is enough for you to come down. That’s the plane ticket right there.”

“Far out,” said Debbie.

On Friday, July 10, the checks arrived in Houston and Tom cashed them. He had neglected to tell the welfare department that he was moving to Texas, and the welfare department, apparently, had neglected to check up on him, so it was put in the odd position of unwittingly financing the final act in the departure of two people from its rolls. Tom made a reservation for a flight Sunday night, July 12. Exactly two months after they had first driven into Houston, Debbie would come back.

Debbie spent her last Friday afternoon in Detroit doing what she usually did on Friday afternoons in Detroit, namely hanging out at Huey’s, a dark and friendly bar in her old neighborhood. Mad Dog, a very big man of thirty with a broad, open face, a handlebar moustache, and a crew cut, met her there and they had a few beers. All the Huey’s regulars gossiped fondly about the events of the evening before, when Mad Dog had gotten drunk, beaten someone up, and spent the night in jail. Somebody said there was a rumor that the Outlaws, a motorcycle gang whose members were occasionally part of Huey’s clientele, were going to move to Texas en masse. The bartender, a bulky man with a goatee, told Debbie she was a traitor for going to Texas; two of his uncles, laid off by Chrysler, were living in Brownsville and working in the oil fields, but they were traitors, too, and besides, they said it was too hot down there.

Debbie was by now used to being teased about Texas, and it wasn’t going to change her mind. As far as she was concerned, on this trip she had given Detroit one last chance and Detroit had failed her miserably. After her grandmother’s death and Mad Dog’s marriage proposal, she had honestly tried to make a go of things there. She moved in with some friends. She looked hard for a job. She saw that her immediate prospects for marriage and family life were probably better there, and it was hard to walk away from that.

But as far as jobs went, there were hardly even any want ads in the paper. Finally a temporary employment service told her she could work for a while at a factory for $4 an hour, but the day before she was supposed to start her purse was stolen and the factory manager wouldn’t employ her without identification. So she had no prospects. She had a quarrel with Mad Dog. She had a quarrel with the friends she was staying with. She moved back to her family’s house, a small place filled with her grandmother’s belongings—rugs, religious icons, ashtrays, plaques, china figurines—and found it depressing. Detroit imposed burdens and bestowed no rewards. Houston was unencumbered. It at least offered possibilities. That was why she decided to go back.

After an hour or two at Huey’s Debbie left to pick up her mother at the bingo hall; then she got a bite to eat and went to Falcon Lanes, a combination bowling alley and rock ’n’ roll club where Mad Dog worked nights as the bouncer. Mad Dog found Debbie a table in the back, and people began to drift in and sit down. Mad Dog was carrying a two-foot black steel-core flashlight, one of the tools of his trade, and he told Debbie he had a gun stashed under his belt. Every once in a while he would sit down and have a beer and expound on his view of Detroit.

Mad Dog said he had earned a Purple Heart in Viet Nam and been shot twice and stabbed four times in Detroit. He said he never ran away from anything and he wasn’t going to run away from his neighborhood now. He said there were only seven people in the city of Detroit named Mad Dog and they all knew each other. That was the kind of city Detroit was. You stayed in your neighborhood. You knew where you stood. You didn’t move. You stuck with your kind. It was awful what was happening now. Mad Dog said people who moved to the suburbs were running away. People who moved to Texas were different. They were doing what they had to do to survive. He got choked up and crushed a plastic drink glass with his fist.

In Houston that same night, Tom went to a topless club on 34th Street in a neighborhood full of warehouses and cue clubs, and made the acquaintance of a dancer there, a girl who wore feathers in her hair. He stayed until the place closed, had a few drinks with the girl, and persuaded her to come back to Class A Maintenance with him. When he woke up Saturday morning he discovered that he had spent $120 in the course of the evening. He didn’t regret it, either. It was the best time he’d had since coming to Houston, and he had arranged to see the girl again.

Like Mad Dog in Detroit, that night Tom reflected on his life, and he decided he was well pleased with it. Joe had recently raised him to $6 an hour, and in a couple of weeks he would have his air conditioning repair certificate. He had come to Houston to start a new life, and he had started a great one. The way he figured it, Class A Maintenance was going to grow, and he was going to grow along with it. As Joe grew, as Houston grew, he would grow. Tom certainly was reaping few rewards so far—he was nearly poor, his life was only barely comfortable—but he chose to see his new hometown as fundamentally different from his old one. For a moment he considered not buying Debbie’s plane ticket after all—as he saw it, he had done a lot for her already—but it was only a passing thought. He went to Joe and borrowed the money he had spent the night before, and then he drove out to the airport and made all the arrangements.

Debbie’s plane landed in Houston at a little after one in the morning of July 13. Tom, clean shaven and neatly dressed, was waiting at the gate. He had lost thirty pounds in Houston, and it showed in his face, which was leaner and less pasty than it had been before.

“Guess you thought I was never getting off,” Debbie said when she saw him. She handed him a canvas bag with a bulky bowling trophy inside it. She was wearing a freshly cleaned pantsuit with a pin on the lapel that said “Mother.”

Tom chuckled, didn’t kiss her, and turned to walk up the concourse. “I drank a whole pint of Jack Daniels last night,” he said presently. “Straight.”

“Guess you had to drink it into your mind that I was coming back,” said Debbie.

“Hell, Debbie,” said Tom, “I was having more fun while you were gone.”

Tom’s truck was parked outside. He loaded the baggage in the back and took off down IH 45, the same highway he had come to town on. Now he had a pickup with Texas plates instead of an Oldsmobile from Michigan, and he was driving fast, dodging and weaving between lanes, familiar with the territory, indistinguishable from a real Houstonian. From the heater knob on the dashboard hung a bunch of feathers. Debbie lit a joint.

“Well, Tommy,” she said, “I’m glad to see you.”

“I’m glad to see you too. Have somebody to talk to.”

“And somebody to go out and party with.”

“I’ve already been partying. See this?” He touched the feathers. “I went out with a girl that wore these. A topless dancer. We’re engaged.”

“No, you’re not.”

“Naw, I’m not,” Tom said, and he seemed to soften a little. “I told you I wanted to marry you. We’ll just see how it works out.”

“Yeah. See how it works out.”

“One thing, Debbie,” Tom looked at her and grinned. “Don’t you have more fun with me than with anybody else?”

The next day Debbie began working at Class A Maintenance. She answered the phone and painted a nice sign to go on the outside. Joe wouldn’t pay her, and she decided she had to find a real job, but otherwise she proclaimed herself completely happy with Houston. Tom got his certificate from Joe, but it turned out to be a maintenance certificate, not an air conditioning one. That would require going to another school, and Tom prepared to do so in the fall. In Detroit, Mad Dog was telling his friends that he was thinking about moving down to Texas after all, but he was still hoping to get Debbie back instead.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Houston