Until a few years ago, we Texans thought we had it made in the shade. The marvel of central air conditioning—in our homes, our cars, our offices, our stores, even our tractors—was the final answer to ninety-degree-heat and ninety per cent humidity: Then came the energy crisis.

Today we are warmer, but we are also wiser. Now that many of us can no longer afford central air conditioners, indeed even room air conditioners, we are coming to realize that spending a summer in a totally air-conditioned city is like spending five months in a meat locker. This decade calls for a different solution to the problem of heat. Not surprisingly, the answer has been, around a long time, possibly since the end of the first Ice Age. The solution to our dilemma is in a word, the fan.

The fan works on the simple principle that the body has a built-in air-conditioning system—sweat—and the evaporation of same. As air circulates across the skin, perspiration evaporates and lowers the body temperature. The greater the airflow, the cooler we feel. Over the years, man has put this fact to use and has devised a variety of air movers.

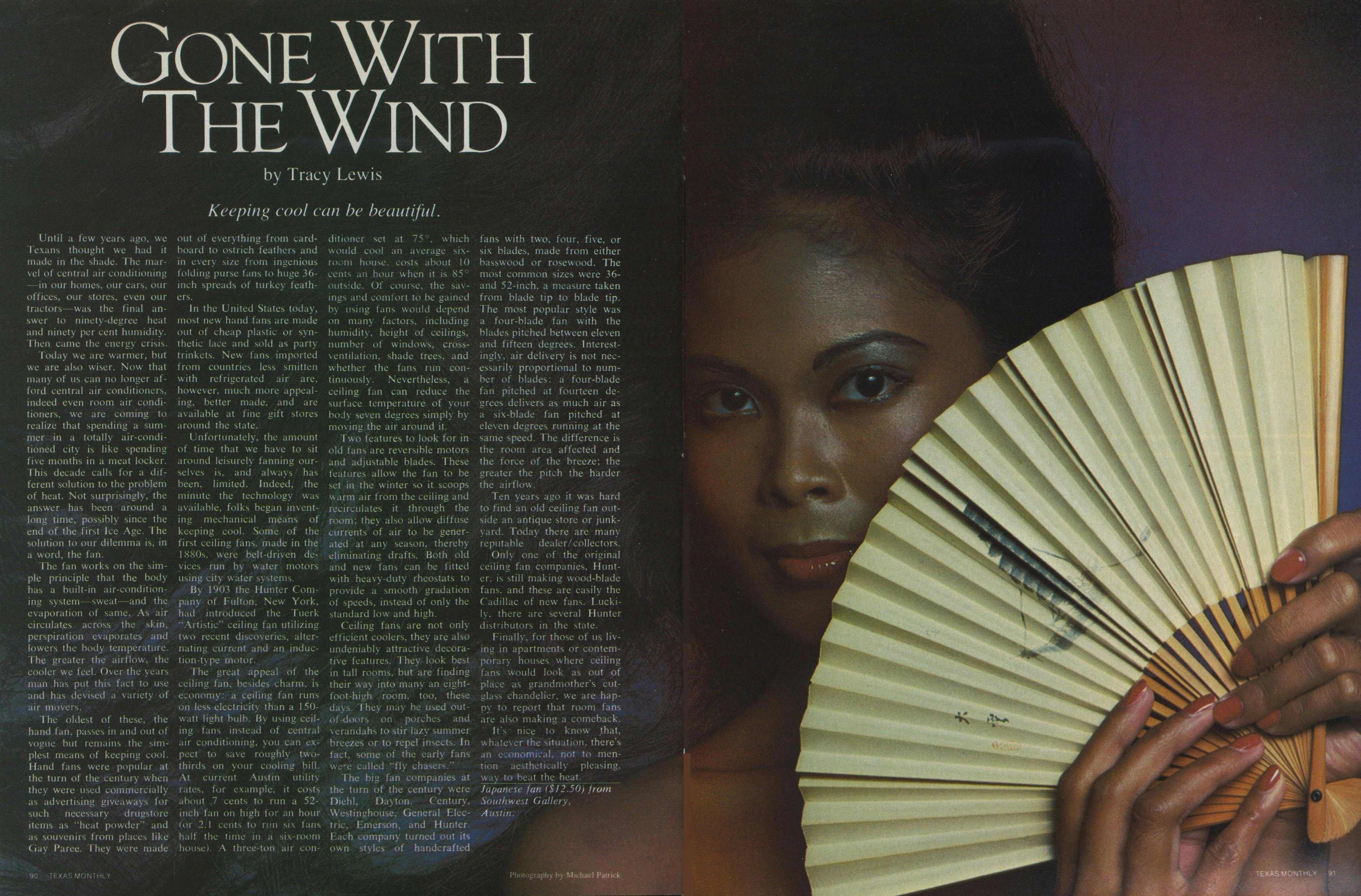

The oldest of these, the hand fan passes in and out of vogue but remains the simplest means of keeping cool. Hand fans were popular at the turn of the century when they were used commercially as advertising giveaways for such necessary drugstore items as “heat powder” and as souvenirs from places like Gay Paree. They were made out of everything from cardboard to ostrich feathers and in every size from ingenious folding purse fans to huge 36-inch spreads of turkey feathers.

In the United States today, most new hand fans are made out of cheap plastic or synthetic lace and sold as party trinkets. New fans imported from countries less smitten with refrigerated air are, however, much more appealing, better made, and are available at fine gift stores around the state.

Unfortunately, the amount of time that we have to sit around leisurely fanning ourselves is, and always has been, limited. Indeed, the minute the technology was available, folks began inventing mechanical means of keeping cool. Some of the first ceiling fans made in the 1880s were belt-driven devices run by water motors using city water systems.

By 1903 the Hunter Company, of Fulton, New York, had introduced the Tuerk “Artistic” ceiling fan utilizing two recent discoveries, alternating current and an induction-type motor.

The great appeal of the ceiling fan, besides charm, is economy; a ceiling fan runs on less electricity than a l50-watt light bulb. By using ceiling fans instead of central air conditioning, you can expect to save roughly two-thirds on your cooling bill. At current Austin utility rates, for example, it costs about .7 cents to run a 52-inch fan on high for an hour (or 2.1 cents to run six fans half the time in a six-room house). A three-ton air conditioner set at 75°, which would cool an average six-room house costs about 10 cents an hour when it is 85° outside. Of course, the savings and comfort to be gained by using fans would depend on many factors, including humidity, height of ceilings, number of windows, cross-ventilation, shade trees, and whether the fans run continuously. Nevertheless, a ceiling fan can reduce the surface temperature of your body seven degrees simply by moving the air around it.

Two features to look for in old fans are reversible motors and adjustable blades. These features allow the fan to be set in the winter so it scoops warm air from the ceiling and recirculates it through the room; they also allow diffuse currents of air to be generated at any season, thereby eliminating drafts. Both old and new fans can be fitted with heavy-duty rheostats to provide a smooth gradation of speeds, instead of only the standard low and high.

Ceiling fans, are not only efficient coolers, they are also undeniably attractive decorative features. They look best in tall rooms, but are finding their way into many an eight-foot high room, too, these days. They may be used out-of-doors on porches and verandahs to stir lazy summer breezes or to repel insects. In fact, some of the early fans were called “fly chasers.”

The big fan companies the turn of the century were Diehl, Dayton, Century, Westinghouse, General Electric, Emerson, and Hunter. Each company turned out its own styles and of handcrafted fans with two, four, five, or six blades made from either basswood or rosewood. The most common sizes were 36 and 52-inch, a measure taken from blade tip to blade tip. The most popular style was a four-blade fan with the blades pitched between eleven and fifteen degrees. Interestingly, air delivery is not necessarily proportional to number of blades: a four-blade fan pitched at fourteen degrees delivers as much air as a six-blade fan pitched at eleven degrees running at the same speed. The difference is the room area affected and the force of the breeze; the greater the pitch the harder the airflow.

Ten years ago it was hard to find an old ceiling fan outside an antique store or junkyard. Today there are many reputable dealer/collectors.

Only one of the original ceiling fan companies, Hunter, is still making wood-blade fan, and these are easily the Cadillac of new fans. Luckily, there are several Hunter distributors in the state.

Finally, for those of us living in apartments or contemporary houses where ceiling fans would look as out oplace as grandmother’s cut-glass chandelier, we are happy to report that room fans are also making a comeback.

It’s nice to know that, whatever the situation, there’s an economical, not to mention aesthetically pleasing, way to beat the heat.

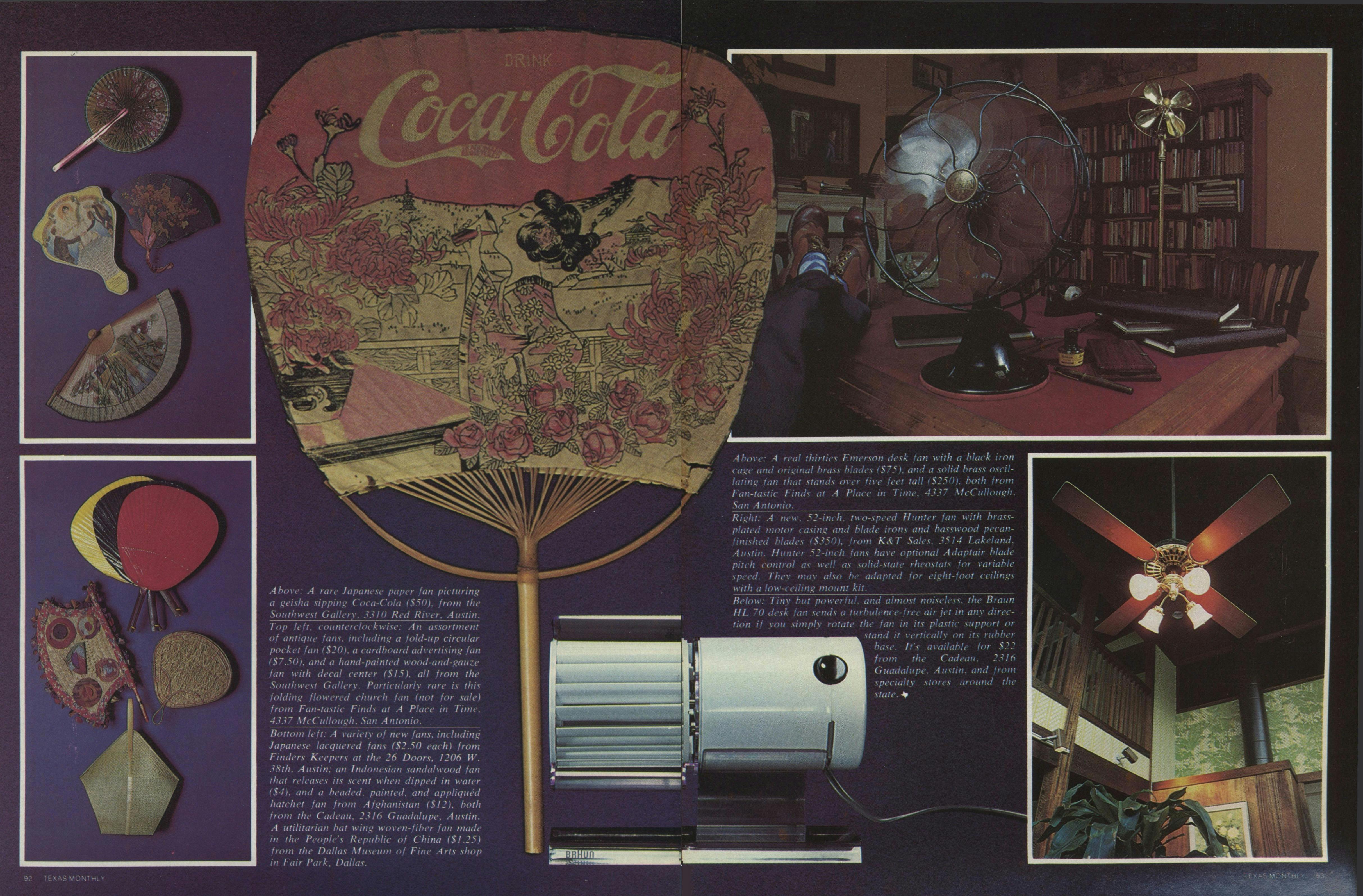

Top left, counterclockwise: An assortment of fans, including a fold-up circular pocket fan ($20), a cardboard advertising fan ($7.50), and a hand-painted wood-and-gauze fan with decal center ($.15), all from the Southwest Gallery. Particularly rare is the folding flowered church fan (not for sale) from Fan-tastic Finds at A Place in Time. 4337 McCullough, San Antonio.

Bottom left: A variety of new fans, including Japanese lacquered fans ($2.50 each) from Finders Keepers at the 26 Doors, 1206 W. 38th, Austin; an Indonesian sandalwood fan that releases its scent when dipped in water ($4), and a beaded, painted, and appliqued hatchet fan from Afghanistan ($l2) both froth the Cadeau, 2316 Guadalupe, Austin. A utilitarian batwing woven-fiber fan made in the People’s Republic of China ($1.25) from the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts shop in Fair Park, Dallas.

Top Right: A real thirties Emerson desk fan with a black iron case and original brass blades ($75), and a solid brass oscillating fan that stands over five feet tall ($250), both from Fan-tastic Finds at A Place in Time, San Antonio.

Below Right: A new 52-inch, two-speed Hunter fan with brass-plated motor casing and blade irons and basswood pecan-finished blades ($350) from K & T Sales, 3514 Lakeland, Austin. Hunter 52-inch fans have optional Adaptair blade pitch control as well as solid-state rheostats for variable speed. They may also be adapted for eight-foot ceilings with a low-ceiling mount kit.

Below Center: Tiny but powerful, and almost noiseless, the Braun HL70 desk fan sends a turbulence-free air jet in any direction if you simply rotate the fan in its plastic support of stand it vertically on its rubber base. It’s available for $22 from the Cadeau, 2316 Guadalupe, Austin, and from specialty stores around the state.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- Fashion