This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

One summer afternoon in 1971, in the little town of Helotes outside San Antonio, a young artist named James Marshall lay in a hammock and drew two tiny dots. Inside the house his mother was watching Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf on TV, and the bickering, cynical voices of the movie’s two protagonists, George and Martha, intruded on his concentration.

The dots were the eyes of a cartoon character, two almost invisible specks of expression in a creature that, as Marshall drew it, began to take the form of a gargantuan blob. He worked quickly, and a little nervously, because his career as a children’s book author was in a critical phase that summer. The year before, he had made his debut as the illustrator of Plink, Plink, Plink, a brief picture book with a text by Byrd Baylor that genially instructed children in how to cope with their fear of the dark. The book was not particularly distinctive or even very successful (Plunk, Plunk, Plunk, one critic called it), but it had earned some kind notices and emboldened Marshall to try again. At the age of 29, with abortive careers as a musician and a teacher behind him, he was convinced that he had finally found his calling.

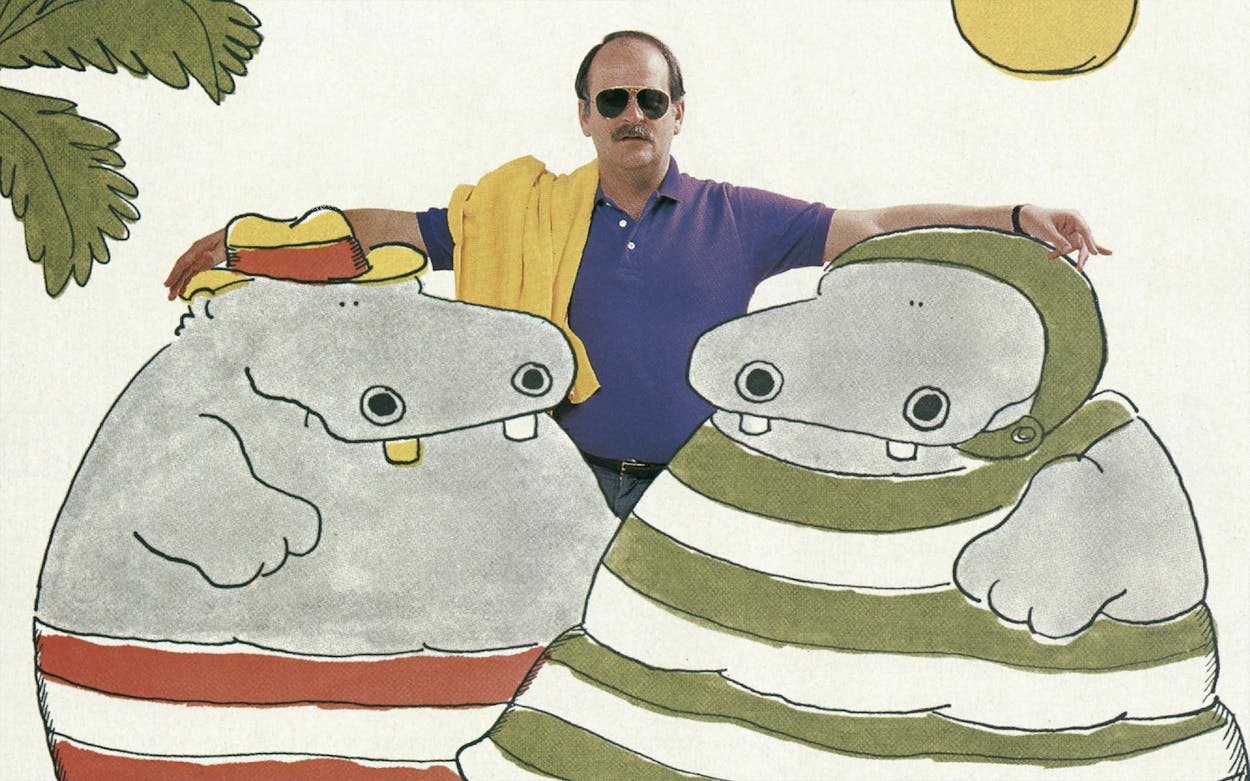

Marshall’s first book had been populated with comic, lurking monsters, rendered in a style that was dense and crosshatched and that owed a debt to Maurice Sendak, who had dominated the field of picture books since Where the Wild Things Are appeared in 1963. But the creature Marshall drew now in Helotes was devoid of such graphic flourishes. Marshall left out the texture and concentrated on the line, and the result was—some would say—historic. That afternoon James Marshall not only found his style—a style as innocent, as sly and spirited as a child’s—but he also invented George and Martha, the two most famous hippopotami in children’s literature.

Actually, Marshall didn’t realize they were hippos until someone pointed this out to him later. He knew who they were before he knew what they were. Unlike their rancorous namesakes on Mrs. Marshall’s television, George and Martha—as they have evolved through the years in a series of six books—treat each other with chivalry and tenderness. Though they are clearly more than friends, their romance, if we may call it that, is exquisitely chaste. The two are prey, however, to misunderstandings and bruised feelings, for despite the gross enormity of George and Martha’s physical selves, their sensibilities are delicate indeed.

My children and I first encountered George and Martha several years ago and have followed their mild domestic adventures ever since. We like the furry house shoes that George wears when he raids the refrigerator at night and the way that Martha sometimes keeps a pencil behind her little nubbin of an ear. We know the history behind George’s gold tusk (he lost the original in a roller-skating accident), and we never fail to notice the souvenir fan from the Alamo that Martha clutches as she reclines on her settee.

The George and Martha books are our particular favorites, but James Marshall is one of the most prolific and successful children’s authors in the country, and his collected works run to more than 75 volumes. Almost all of these are picture books with a succinct comic text, the sort that are meant to be read aloud night after night after night to sleepy preschool children. As a parent, I’m partial to James Marshall’s books because they do not get on my nerves; they wear well, and there’s something authentic in their hold on a child’s imagination, some quality in them that I trust. Parents soon learn to recognize which children’s books are really speaking to children and which are only pretending to (see The Little Prince). Marshall’s work is the real thing—filled with hysterical energy, dumb jokes, and now and then an appealing glimpse of the macabre.

Consider, for instance, the Stupids, perhaps the most irresistible characters ever to inhabit a children’s book. The Stupids—whom Marshall created in collaboration with writer Harry Allard—are a family of cheerful lamebrains who wear their socks on their ears and eat their breakfast in the shower (“My eggs are all runny,” comments the father, Stanley Q. Stupid). Marshall draws them with his patented eye dots and with doltish grins that perfectly convey an inner life of excruciating dimness. The humor is broad but nervy (the latest title in the series is The Stupids Die) and has been known to outrage certain proper souls who do not feel that the Stupids’ limited mental powers should be held up to ridicule.

Besides George and Martha and the Stupids, Marshall’s most popular books are those that make up the Miss Nelson series, which he also wrote with Allard. Miss Nelson is an angelic teacher who, when discipline is required, mysteriously drops out of sight to be replaced by a ferocious educator named Viola Swamp. Of all the characters that Marshall has created, the witchlike Miss Swamp has the greatest currency. The Miss Nelson books are read aloud in so many households and elementary schools across the country that the mention of Viola Swamp’s name sends children into mock fits of fear and trembling.

In an age when children’s books aspire to ever-greater sophistication—with authors like Sendak and Chris Van Allsburg producing mysterious, melancholy volumes that have more to do with dream states than with the huffing-and-puffing steam engines of yore—Marshall’s work remains disarmingly direct. There are moments of inspired, unashamed silliness in these books that linger in the mind with surprising tenacity. I’m thinking of the title character in Portly McSwine dropping his pants to receive an inoculation for the swine flu; or Mother Hubbard’s dog—in Marshall’s incomparable version of Mother Goose—exclaiming, upon seeing the old lady’s empty cupboard, “I can scarcely believe it!”; or the scene in Yummers Too: The Second Course in which two dogs with bandannas over their faces attempt to steal a four-tiered wedding cake from Bud and Pansy’s French Bakery.

“He’s a rarity among all of us,” Sendak says of Marshall, “in that he has genuine comic spirit. He’s really got it. You either have the instinct to speak directly to children or you don’t. You can’t pick that up.”

James Marshall lives in rural Connecticut, in a former mill town called Mansfield Center, but his books are so packed with Texas allusions—from the state flags and maps in Miss Nelson’s classroom to the bolo tie and boots on the boy who’s dancing around the mulberry bush in Mother Goose—that his regard for his native state has the feel of an obsession.

“I’ll always love Texas,” he told me when I visited him in Connecticut last January. “Especially West Texas. But I’ve become a New Englander too. The only problem is I’ve never gotten warm. Not once.”

He was lighting a fire in a big Franklin stove that dominated the living room of his house, a nineteenth-century frame structure that was once a general store. The house was small but efficiently laid out, with two bedrooms and a kitchen downstairs and an attic studio overhead. Marshall lived here alone, except for a cat named Marcel and another whose name I didn’t catch but who was yowling at the door, wanting to be let in from the snow.

Marshall opened the door for the cat and then stood looking at the fire for a moment until he was satisfied it was going to catch. Finally he sat down in front of a set of floor-to-ceiling bookshelves that were crowded with cookbooks, art books, biographies, and volumes of English history. He could have been any author in his lair.

I looked for a resemblance to Lamar J. Spurgle, a character in one of Marshall’s books called The Cut-Ups, whom the author admits is a self-portrait. Spurgle is an archcurmudgeon, a former assistant principal who has “had enough kids to last him a lifetime” and lives in a house surrounded by yard signs that say “You’ll Be Sorry” and “I Show No Mercy.” Marshall portrays him with beady eyes, a villainous mustache, and a jawbone that juts forward like a mammoth’s. Adjust that image for reality, and you see a vague similarity: a man of 45, of medium height, with dark brown hair and eyes, but utterly without Lamar J. Spurgle’s vindictive glower. Marshall is, instead, kindly and rather bookish, with a sense of humor that is deeper and more subdued than you would expect from the manic humor in his books.

“People have very odd ideas of what a children’s writer should be like,” he told me. “Children always expect me to look like a hippopotamus, and adults assume that by nature I have to be a little off the wall. They expect me to be zany. That’s a word I’d like to have wiped off every dust jacket of every book I’ve ever done—‘Marshall has created another zany cast of characters.’ ”

The sedate cutup was born in downtown San Antonio at the Nix Hospital and grew up sixteen miles outside of town on an old family farm off Fredericksburg Road. His father worked for the Southern Pacific railroad, but back in the thirties he had had his own dance band and appeared on radio shows. Marshall’s mother, who used to drive him to school in an old Meteor hearse, was musical as well. She sang in the church choir and at musical teas.

His father’s people came from Marathon, where young Jim would visit in the summer extracting family history from relatives with names like Uncle Ode and Big Mama. Wandering through the Marathon cemetery, he breathed the air of rangeland gothic.

“My great-grandparents are buried in Marathon,” he said. “Around 1910 my great-aunt Inez died of typhoid fever as a child. My grandfather saw her buried. Forty years later he was there as a witness when they moved the cemetery. He recognized her. In that dry limestone she’d just sort of withered. She was bald when she died because the typhoid made her hair fall out. Fifty years later there was still fuzz on her scalp. That story always impressed me.”

Marshall remembers reading Tubby the Tugboat and The Little Engine That Could, but he does not recall any interest in children’s books that went beyond the ordinary. When he was old enough to read on his own he developed a passion for Anglo-Saxon history, and he liked to while away the occasional afternoon at Henry’s Ice House, drinking Big Red and reading ghoul comics—“You know, the kind where Brad digs up Janet, and she says, ‘Oh Brad, I hope you don’t mind the stench.’ ”

In the second grade a teacher laughed at his drawing of a tree. Marshall later got his revenge by creating the character of Viola Swamp, but at the time he was traumatized, and he was a grown man before he could draw with any sense of confidence. His creative energies went instead to music. He played the viola well enough to think of it as a career. His parents sent him to music camp in Interlochen, Michigan, and later he went on a scholarship to the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston. On his way to a Pablo Casals festival in Puerto Rico, he was jerked out of his airplane seat during a rough landing and injured his hand—not badly, but enough to ruin it for playing the viola. Just like that, he was no longer a musician.

In the aimless years that followed, Marshall went back to Texas and attended Lamar University in Beaumont, where his father had been transferred and which was to Marshall the least-interesting city on earth. Fleeing Beaumont, he returned to San Antonio and attended San Antonio College and later Trinity, studying French under Harry Allard, his future collaborator. Finally he moved back East, where he graduated from Southern Connecticut State University with a degree in French and history.

Wanting to live in Boston again, Marshall applied for a teaching job at a Catholic school there. The mother superior asked him if he could speak Spanish. The French major lied and said yes. Soon he found himself in front of a class half-filled with Puerto Rican kids, charged with teaching them their native language.

“I made a deal with them,” he remembers. “I told them if they just came to class they’d get a C. If they helped teach me Spanish, they’d get an A.”

The strain of faking it began to wear on Marshall, and when he came home at night he relaxed by drawing pictures of animals. He didn’t know how to draw people. At the advice of a friend he took some of his drawings to Walter Lorraine, a children’s-book editor at Houghton Mifflin, and Lorraine liked them enough to try out the fledgling illustrator on Plink, Plink, Plink.

Houghton Mifflin brought out the first George and Martha. It was selected by the New York Times as one of the ten best illustrated books of 1972, and the scores of books that have followed have helped secure James Marshall a place in the peerage of name-brand children’s authors. His books sell usually between 30,000 and 50,000 copies apiece, and he produces them at such a prolific rate that he now uses three different publishers. His income is considerable, and besides the Connecticut house, he owns an apartment in New York and until recently kept another on Nob Hill in San Francisco. Though he is a great popular success and his work commands the esteem of Sendak and others, he has not yet been brought into the full light of critical respectability. For instance, Marshall has conspicuously never won the Caldecott Medal, the prestige award of children’s picture books. The Caldecott’s influence is unquestionable, since the books that win the award are routinely bought by the libraries that make up the crucial segment of the children’s book market. The Caldecott judges lean toward books with just the sort of gorgeous illustrations and ennobling themes that Marshall conscientiously avoids.

But his work manages to find its own way in the marketplace. At bookshop signings, he has sold two thousand books in a single day and witnessed the sometimes hysterical adulation of his readers.

“I’ve got some fans who are just certifiable,” he said. “A friend brought me a personal ad he’d seen in some underground newspaper that read ‘Male—thirty-five years old—loves to run around the apartment naked. Reads Kahlil Gibran and James Marshall.’ Whenever I do an appearance there’s always someone who dresses up like Viola Swamp. One time this woman did that at a signing. She ran in screaming and started hitting me on the head with a ruler. A little girl was standing there, and she was so scared she went into a catatonic fit. They carried her out like a surfboard.”

I asked Marshall how long it takes him to do a picture book, and his face assumed a look of polite exasperation. The question is wearisome because it is so common and difficult to answer.

“At the beginning of my career I would tell librarians how long it would take, and my stock would go down. I could do a thirty-two-page picture book in six weeks if I was inspired. The first Miss Nelson was done in twenty-four hours. The next one took two years off and on.

“I work very hard to keep the line very simple. That line has to tell a story. The problem is, if you do get it simple, and it looks like it was done in an hour, people will say it looks like it was done in an hour.”

Walter Lorraine, Marshall’s longtime editor at Houghton Mifflin, thinks Marshall is “as much a genius as anyone I’ve seen since Edward Lear,” but he finds himself fretting at times over his author’s seeming indifference to an overall career strategy.

“Jim is totally intuitive,” Lorraine says. “He’s incapable of actually planning a career. He does it by whimsy. But he can get away with it because he’s a genius. But he’s never been challenged to grow beyond the level of excellence he’s already reached. If he were, maybe it wouldn’t work. Maybe it’d be a disaster.”

Maybe it would. Sitting in Marshall’s living room, listening to his eloquent opinions on Chekhov and Kawabata as the fire burned in the Franklin stove, I had to keep reminding myself that this was an author who wrote about Portly McSwine and Stanley Q. Stupid. The whole point of his books is that they do not strive for greatness, but for yuks. Their humor is wild, undisciplined, even defiant. And yet Lorraine has a point—something in Marshall’s work encourages you to expect more. A great children’s book, like a great work of adult literature, gently ushers the reader’s mind into deeper considerations. What is the George and Martha series, after all, but an extended meditation on the nature of friendship and the need for solace in an imperfect world? Will Martha be able to accept George after he loses his tusk in the roller-skating accident? Will she triumph over his implicit rejection of her when he pours her vile split-pea soup into his loafers while her back is turned?

Marshall’s techniques invite the same sophisticated scrutiny as his themes do. “He doesn’t just draw,” Harry Allard marvels, “he creates patterns on the page. He has a genius for negative spaces, for interval. Some of his work is like a fine Japanese print. He sometimes dares to put almost nothing on the page. If he draws a chair, he focuses on the salient qualities of the chair. There’s a tension between the sophistication of the design and the apparent primitiveness of the drawing.”

If Maurice Sendak is Proust, Allard maintains, then Marshall is Hemingway.

Marshall himself can be induced to talk seriously about his work, but he can only say so much before he begins worrying about sounding pompous.

“Look,” he said, “I want to write funny books. I write to entertain. I think this tendency to overanalyze stems basically from the fact that people are ashamed of children’s literature and they want to turn it into something eternal. There are a lot of inferiority complexes in this business. Anything having to do with children is suspect, you find. Go to a party and see who congregates around the pediatrician and who congregates around the brain surgeon. Look at the salaries of teachers. There’s always the suspicion of being second-rate.”

In Marshall’s case, that suspicion is laid to rest by the way his books persist so strongly—and sometimes so eerily—in the imagination. Leaving aside the sweet-tempered tribulations of George and Martha or the slapstick befuddlement of the Stupids, much of Marshall’s work casts a shadow that unformed minds seem to find thrilling. In the Miss Nelson books, a kindly teacher is suddenly and without explanation supplanted by Viola Swamp, a nightmarish development that is sure to preoccupy a child even after he learns that Miss Swamp is really Miss Nelson in disguise. In a series of books that began with Three by the Sea, children meet in some lonely spot and attempt to frighten each other out of their wits. One tells the story of a yellow-eyed monster rising up out of the sea in search of a snack (“Monsters really like kids. On toast!”). Another recounts the story of a boy who visits an old lady in the forest who, while admitting to being a witch (“I cannot tell a lie”) hastens to reassure her guest. “Don’t worry,” she says, “I only eat potatoes.” Whereupon she casts a spell and turns him into a potato and eats him—mashed—for dinner.

Marshall’s books are filled with such moments, with characters and situations that are glancingly grisly but always lighthearted.

“It’s a balancing act,” Sendak says. “He depicts the tenderness of friendship and affection between characters, and underneath it all is the abyss—the fox that will eat you up and the snow that will cover you. There’s a subtext to all work that’s good, and his is about the fragile but essential connections between human beings. Like Beatrix Potter does with Peter Rabbit, he covers a very lethal subject—just how frail a rabbit is.”

Marshall’s books are very much the products of the boy who was fascinated by the Marathon cemetery and by ghoul comics; who as a man delights in recounting the story of how his cat Marcel was almost abducted by the proprietor of a Chinese restaurant and served in a sweet-and-sour sauce; who shows visitors a prized coffee-table book about mummies and quotes the wit and wisdom of a friend he refers to only as Ed the Mortician. As funny and lighthearted as his work is, it does not pretend that death and hurt do not exist.

“I worry about a lot of things,” he said, after putting the mummy book back onto the shelf. “The environment, nuclear disasters, the general ugliness of the world. But then I go out to West Texas, and I think how beautiful it all still is.”

While Marshall disappeared into the kitchen, I leafed through one of his sketchbooks. It was filled with preliminary drawings for a West Texas story featuring a ranch heiress (a mole) named Roberta Molesworthy.

“She’s very rich,” Marshall said, handing me a cup of green Japanese tea. “She keeps losing things, like her plane and her yacht. Her father says things like ‘Really, Roberta, those things cost money.’ She ends up in an adventure—I’m not sure what yet.”

There were sketches as well of other characters I recognized from the Yummers books, the rapacious Emily Pig and her more moderate escort, Eugene, a turtle. Next to a quick sketch of Eugene reposing in a hammock, Marshall had commented: “Looks creepy. Too bald, too snakelike.” Other sketches depicted Little Red Riding Hood and the Gingerbread Man, subjects well-suited to Marshall, since both waver between comedy and deadly menace.

Upstairs in his studio, he showed me file drawers overflowing with projects in various stages of completion.

“This is a Port Aransas story I’m doing,” he said, sorting through some pencil sketches. “And this is a book about a family of cows called the Hoovers. It starts out, ‘From the day the Hoovers discovered they could dance, their lives were not the same.’ ”

The attic room had a low ceiling and walls that angled down from it, following the roof line of the house. Marshall’s drafting table sat near the front window, through which came the muffled midwinter light of New England. On one wall was a framed letter written in braille, with a translation beneath. “Dear Mr. Marshall, I like your books that you make. Thank you for all the books you made. I love you, Mr. James Marshall. I am 7 years old. My birthday is on Oct. 17. Your friend, Darlene Coleman.”

I asked if I could watch him work. He said sure. Sitting down behind the drawing table, he opened an oversized sketch pad and inserted a pencil in an electric pencil sharpener. He explained that he was in the early stages of a book called Fox on the Job, the latest in a series of books about a young fox (said by some to resemble James Marshall) who is good-natured but chronically deficient in his responsibilities. At this point in the story Fox was delivering a pizza to a ladies’ tea party hosted by a matronly rabbit named Mrs. O’Hara.

Marshall drew a line down the center of the page and quickly sketched in the setup. Two sidewalks converged at the corner of a building. The viewer’s perspective was such that he could see both sidewalks at the same time. On the left sidewalk Marshall drew Fox, rushing along with the pizza box, his view of the other sidewalk blocked by the building. Marshall sketched with what seemed to me astonishing speed: one moment Fox was simply there, appearing beneath the artist’s hand, which moved with the assured, rapid flurry of a hummingbird’s wing.

“This has to look like a hill,” Marshall said, erasing and refining the forward angle of the building, then adjusting the line of the sidewalks to conform to it. “He’s got to be coming down the hill —and fast. I’ve got to give him a sense of speed. Maybe I should put his ears back. Maybe I should put him on a skateboard!”

Marshall looked up and soberly regarded the wall on the other side of the room. “Sometimes I look at what I’m doing and think, ‘A grown man, sitting here wondering whether or not to put a fox on a skateboard.’ ”

He held this thought for a moment longer without seeming to come to any conclusions about it, then went back to his drawing. He decided to forget about the skateboard, but setting the fox’s ears back helped provide the illusion of speed, and Marshall then turned his attention to the other sidewalk.

“Now here comes Fox’s sister, Louise, around the corner with a box filled with her pet mice on her way to the vet to get their shots. And the box looks just like a pizza box.”

He drew the figure of Louise in a flash and then took a gray smudger and filled in the windows of the building. Later, when the preliminary sketches for this book were finished, he would put them on his light box and use them as an underpinning for a more considered pencil version. Then he would bring them back to the drafting table to ink and color them in with watercolors.

Marshall scrutinized the scene he had created: a boy fox and a girl fox, each carrying flat white boxes, rushing blindly along toward a mutual destination.

“Now, do we have a crash coming here or not?” he wondered.

After due consideration he went on to the next illustration, in which Fox and Louise collide.

“How about this? Does this look like a collision?” he asked.

It looked like it to me, though I ventured it would be more vivid if Louise’s mice were shown flying through the air.

“No, I can’t have that. See, I don’t want the mice falling out of the box, because Fox picks it up instead of the pizza box and delivers it to Mrs. O’Hara for the tea party.”

Leaving the collision scene for the time being, Marshall went on to draw Fox delivering the box to Mrs. O’Hara. She appeared in a few quick strokes, a formidable, disapproving rodent—exactly the sort of person you would not want to deliver a box of mice to by mistake.

Now—how to best convey the ensuing chaos. Should we see Mrs. O’Hara as she opens the lid of the box and is frightened half to death by the mice, or is it better to end with Fox walking away from her house, satisfied with a job well done, while from the closed front door of Mrs. O’Hara’s house a shriek erupts?

I suggested the former version, mainly because I wanted to watch James Marshall draw a mouse. Deep in thought, he stared at the sketch pad as the snow started to fall outside and another cat begged to be let in the front door.

“No,” he said finally, turning the page and starting another sketch. “Let’s leave it to the imagination.”

- More About:

- Books

- Art

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- San Antonio

- Marathon

- Helotes