I was recently on a panel discussing what many consider an oxymoron: the future of publishing. We had some laughs about being in the buggy whip business, and then all of us, authors and audience members alike, patted ourselves on the back for loving books. This made me nervous. I worry when people are so publicly proud of liking something; it seems the hallmark of a doomed activity. Give me private pleasures that you would never dream of mentioning—say, self-abuse. Now, there’s a pastime that’s going to endure.

At the end we “had time for a few questions.” One of a group of high school girls asked everyone on the panel, “Why did you become a writer?” I already knew not just the correct answer but the correct facial expression. The correct answer is “I always knew I wanted to be a writer,” and it is best delivered while looking off toward the heavens like Joan of Arc listening to the voices of saints dictating her destiny.

I don’t doubt in the slightest that the writers whom I’ve heard say they “always knew” they wanted to be writers were, in fact, put on this earth to fulfill their destiny and bring forth unto a waiting world Sphagnum: The Trilogy. And having uttered those words a few times myself, I know it sounds a lot better than “I always knew I wanted to be an assistant manager at Wendy’s” (even though an assistant manager makes more and dresses better).

As the other panelists spoke modestly about being instruments of God, I wondered if I should make my own tawdry admission: I became a writer to make money. Like becoming a fire spotter to meet people, this reason has always been ridiculous. Given the past few years in publishing, it is now pathetically laughable.

My first published stories appeared in True Confessions magazine. I’d stumbled upon the truth market while I was in France. Trying to learn something more than “Où est la bibliothèque?” I started reading photo romances, a cross between romance novels and comic books, only with photos. Instead of asking one another where the library was, the characters said things like “Oh, Guillaime, the fragile bird of love, once crushed to the earth, will never fly again” (or, in the colloquial French, “Ah, Guillaime, zee frageel baird of love, once crushed to zee airth, will nevair fly again”). It was writing so crappy that, for the first time ever, a stunning thought formed in my brain: “I could do this.” After my return to les États-Unis, I sought out a comparable market and discovered pulp fiction.

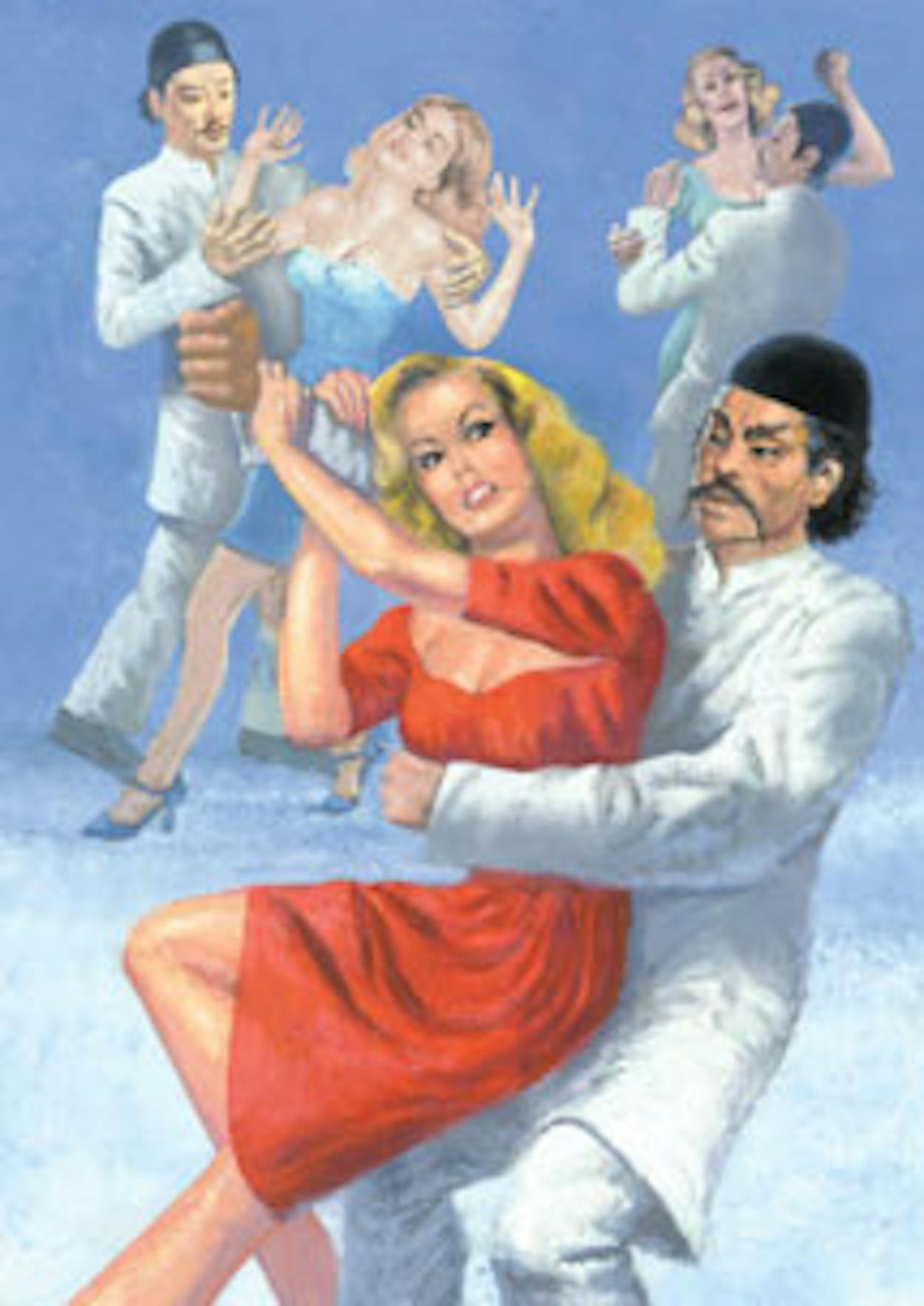

Ever the grade-grubbing nerd, I tackled this enterprise by overresearching. I learned that, unbeknownst to me or anyone else not making their literary purchases exclusively at Circle K, truth mags had been around since at least 1919, when a story with the title “One Awful Night” appeared (“Chinese crooks gobbling up the girls by the wholesale and shipping them to the foreign markets”). To be followed several years later by “Dope” (“Of all the lures which lead men and women to destruction, none is more insidious than dope”). The classic first-person, blue-collar exposés didn’t hit their stride until the fifties, when they featured anonymous revelations like “Setup for Sinning” and “Dirt Poor and Desperate! We Traded Our Baby for a Tractor.” In the sixties, writers ripped them from the headlines: “Bobby Kennedy Started My Love Affair” (“He was in our town less than an hour. But that was long enough for my whole life to be changed”).

By the time I got into the game, in the seventies, pulp fiction was going the way of the buffalo, with tepid offerings along the lines of “The Love Game I Played on My Bingo Nights Out.” Nonetheless, I was paid hundreds of dollars to confess that I had kidnapped my own son, slept with his karate teacher, seduced my parish priest, and stolen my mother-in-law’s meat loaf recipe (and never asked how an unmarried, childless anthro major could have gotten so busy). If the top-tier Trues—True Confessions, True Romance, True Story—didn’t want my masterpieces, I’d turn around and ship them out to the Moderns—Modern Love and Modern Romances. If the Moderns didn’t bite, I’d do some brisk rewriting for the ethnic market. Et voilà, there I was, kidnapping my own black child, sleeping with his black karate teacher, seducing my black parish priest, and stealing my proud black mother-in-law’s meat loaf recipe. Then I would ship that hot mess right back out to Black Confessions, Black Romance, and Bronze Thrills.

Last year I published an essay on Salon, “the award-winning online news and entertainment Web site.” (Just ask them.) When the payment for that piece arrived, I employed the faltering math skills that are probably the real reason I became a writer and concluded that I was making less while writing for one of the premier Web publications than I had when I was typing pulp fiction more than three decades ago.

I pretty much blame the bloggers for the crash of the writing economy. Just like Bill Clinton and the teen girls with self-esteem issues who collapsed the sexual economy by declaring a certain act “not sex,” bloggers have wrecked the market. Eerie parallels abound. In both, there is the distant dream of hitting it big (with a book deal or an invitation to the prom), yet neither pays off frequently enough to justify the repetitive stress injuries.

Such were my thoughts as the panelist beside me finished up her answer. I wondered if it was my duty to tell the young ones of a time when writers actually got paid for confessing shameful secrets, like wearing a badger costume while having sex or owning a PT Cruiser. When girls got engagement rings and dinette sets in exchange for the favor that isn’t sex anymore. But the high schoolers were all so happily absorbed Twittering about what they’d had for lunch that I decided against it.

The moderator repeated the question. “Sarah, why did you become a writer?”

I almost started to share my thoughts on white slaves and giving it away for free. Instead, I lifted my eyes to the heavens, listened to the voices, and replied, “I always knew I wanted to be a writer.”

Listen to a podcast reading of Hack Like Me.