He was a prideful old man who had logged millions of miles, made plenty of money, and forced a president from office. But on the late summer evening when he returned to Washington to investigate Congress, Leon Jaworski was still fighting off the sharks. It was just like before Watergate. First they had attacked him in public, then they had slandered him in private. Invariably, they charged straight for the center of his own tender underbelly: his honor and propriety. And no matter how well he defended himself, Leon Jaworski always took each new accusation personally.

“I don’t give a damn about success, I really don’t,” he confided, his voice cracking. “But when they take my name in vain, that is when it hurts. And every time you get in a public situation, sons of bitches are gonna come along and do this to you.”

Nevertheless, Jaworski was in a fairly good mood. For most of the flight up from Houston, he explained the conflicts and controversies of his life in good-natured tones, occasionally stopping to sip a beer, peruse the Sunday papers, tell the latest Aggie joke, or chat about the weekend he had spent on his ranch in Central Texas. In the sterile light of the first-class cabin, his hair, which was almost whiter than white, contrasted sharply with his face, which had a workingman’s tan. He seemed much younger and more animated than a man of 71. His head and shoulders were quite broad, his trunk looked exceptionally trim and sturdy. With deep, downward furrows around his chin, a large, bulbous nose, and soft green eyes, he managed to appear both dignified and down-home, relaxed and serious.

Although he struggled constantly to restrain himself, Jaworski often could not keep from lashing back at his critics, vituperatively denouncing both the accusations and the accusers. In the end, he would always catch himself, then apologize for the force of his response, while remaining unwaveringly faithful to its substance. “I don’t give a damn what the bastards say about me,” he asserted at one point, “as long as I have a chance to tell my side.” Then he added: “If history wrote that I was trying to be forthright and honest, that’s all I want.”

When the plane landed at Dulles Airport, Jaworski maintained his familiar public style, a slow, deliberate casualness. With notable ease and sense of pace, he got up from his seat, brushed the wrinkles from his suit, picked up his squarish black lawyer’s case, retrieved his hang bag from the rack, and filed into the plane-to-terminal bus. Although most people think of Jaworski as a short, almost Napoleonic figure, I could see standing next to him that he really is, as he said, nearly five feet eleven. Despite offers of assistance, Jaworski insisted on handling both pieces of luggage himself. “It’s all right,” he said without expression. “I’m accustomed to it.”

When the bus docked at the gate, Jaworski grabbed his black case with one hand and his hang bag with the other and walked down the ramp to face the waiting press.

No one bothered to ask why Jaworski had gotten the call again. Since Watergate, he has assumed a nearly mythic status in the woebegone realm of American public figures. In an age of skepticism, Leon Jaworski is, for many people, a rare personification of truth and justice. Though he testified against a bill to create a permanent special prosecutor, he has come to be relied upon as the chief defender of the nation’s scruples, a kind of hired gun for public morality whose motto could well be, “Have Conscience, Will Travel.”

But still the doubts about him persist. This time they began when Michigan Republican Congressman Harold Sawyer encouraged reporters to inquire about Jaworski’s possible role in foreign payments of $2.1 million admittedly made by Anderson, Clayton, the giant Houston-based conglomerate. Subsequent news stories brought up the fact that his law firm, Fulbright & Jaworski, and Jaworski himself have been actively lobbying Congress in recent months, especially in opposition to the creation of a consumer protection agency. Meanwhile, his peers and competitors back in Texas asserted that he was simply going off on another ego trip designed as an advertising gambit for his Houston law firm. Even his old friends at the Washington Post had second thoughts about him. After first praising his being selected to head the Korean probe, the Post ran a rare follow-up editorial considerably modifying its enthusiasm and wondering aloud if Jaworski’s “solid reputation for integrity” could withstand the “apparent conflict” of his “investigating the members of the House . . . while remaining a partner in a law firm whose practice has included, and presumably will continue to include, efforts to influence the course of legislation.”

As usual, Jaworski responded quickly. Despite being a longtime director and outside legal counsel of Anderson, Clayton, he denied knowing about the foreign payments until they were disclosed in a report to the SEC and pointed out that Congressman Sawyer had been an attorney for a company that Anderson, Clayton had been trying to take over. Jaworski also promised that “there will be no effort on my part to influence any legislation,” and declared that his role in the Korean investigation “is purely personal, and the firm is not involved in any way.” But Jaworski’s answers seemed merely to beg the question. For the fact is that Jaworski has succeeded in living two contradictory lives—the first as a public prosecutor and defender, the second as a big-time lawyer, banker, and corporate heavyweight. And each time he shuttles back and forth, Jaworski must reconcile one life with the other.

Since embarking on the Korean probe, Jaworski has encountered the same sort of suspicions he faced when he became Watergate special prosecutor. “The assumption that the White House made when they picked him for Watergate—that he is basically conservative and a protector of the establishment—is essentially correct,” said one former Watergate staffer.

Many who know Jaworski from his life in private practice are also skeptical, but for different reasons. For as he became prominent in the world of big Texas banks and law firms, Jaworski also became increasingly controversial. Over the years, he has been accused of a number of specific ethical violations and conflicts of interest ranging from his handling of foundation business to his representation of clients like notorious gas utility wheeler-dealer Oscar Wyatt. Not surprisingly, most of Jaworski’s critics refuse to discuss their grievances without the protection of reporter-source confidentiality (which says more about the world in which Jaworski operates than it does about Jaworski himself), but their names are scattered throughout past public records and include such establishment figures as the late Jack Binion, the late Dillon Anderson, trial lawyer Frank Harmon, the heirs to the Andrau fortune, and the friends and supporters of John Connally, many of whom will never forgive Jaworski for failing to stop Connally’s bribery trial.

Even Jaworski’s cronies have criticized him on occasion. About a month before Jaworski was asked to take over the Korean probe, for example, his old friend Waggoner Carr accused him of ethical misconduct and asked the State Bar to investigate him after Jaworski, without reviewing the evidence, called publicly for the ouster of Carr’s client, embattled former Texas Supreme Court Justice Don Yarbrough.

A few lawyers go so far as to question Jaworski’s ability in the courtroom. “I think he’s been way overblown,” says noted West Texas trial lawyer Warren Burnett. “Outside of Watergate, Leon Jaworski hasn’t tried a case in years.” Some connoisseurs of courtroom tactics have even questioned Jaworski’s Watergate performance. Although he was successful in his attempt to get the Supreme Court to force Nixon to turn over the critical presidential tape recordings that led to his fall from office, Time magazine remarked that Jaworski’s assistant Philip Lacovara, who later preceded him as chief counsel in the Korean probe, had saved Jaworski’s case by his cogent arguments.

But more than anything else, Jaworski’s critics fault him for failing to admit that he is who he is: an establishment power broker who, like most of his peers, looks more to the “morals of the marketplace” in much of his business dealings than to the higher standards he perpetually preaches.

“The main objection I have is his holier-than-thou attitude,” says one Texas establishment figure who himself has a long record of public service. “Jaworski goes around sermonizing like he’s above it all when he and the other members of his law firm have done all the things everybody else has. He’s stepped on a lot of people.”

Then, too, there is the subject of Jaworski’s ego. “Anyone who knows him knows that he struts sitting down,” observed one Texas attorney. “What a lot of lawyers resent is that he’s always trying to get himself in the limelight, and he always pretends that it has nothing to do with his ego, only the greater good.”

In our first interview Jaworski was ecstatic—virtually intoxicated with his own accomplishments. Sitting there in a wooden armchair in his office, he would preen and posture, examine the manicure of his nails, stroke the back of his head, then lean over with boyish excitement and describe some highlight of his life. As our interviews progressed, I would see him pass through a whole range of gestures and emotions, from caricatures of pride and pomposity to sadness, anger, and unfeigned humility.

In the end, I found Leon Jaworski to be, for all his self-importance, basically honest, extremely likable, and generally misunderstood. While virtually no one denies that he has a tremendous ego, his critics charge that he is a man motivated only by his ambitions. His supporters, on the other hand, protest that he is a great patriot driven by conscience. In fact, Jaworski is both a man of ambition and a man of conscience, and his whole life has been the struggle to satisfy those two sides of himself. In the process he has lived the classic tale of a second-generation immigrant who overcame hardships—language, name, and social discrimination—to climb to the pinnacles of power and prestige, only to find himself compelled to climb higher still.

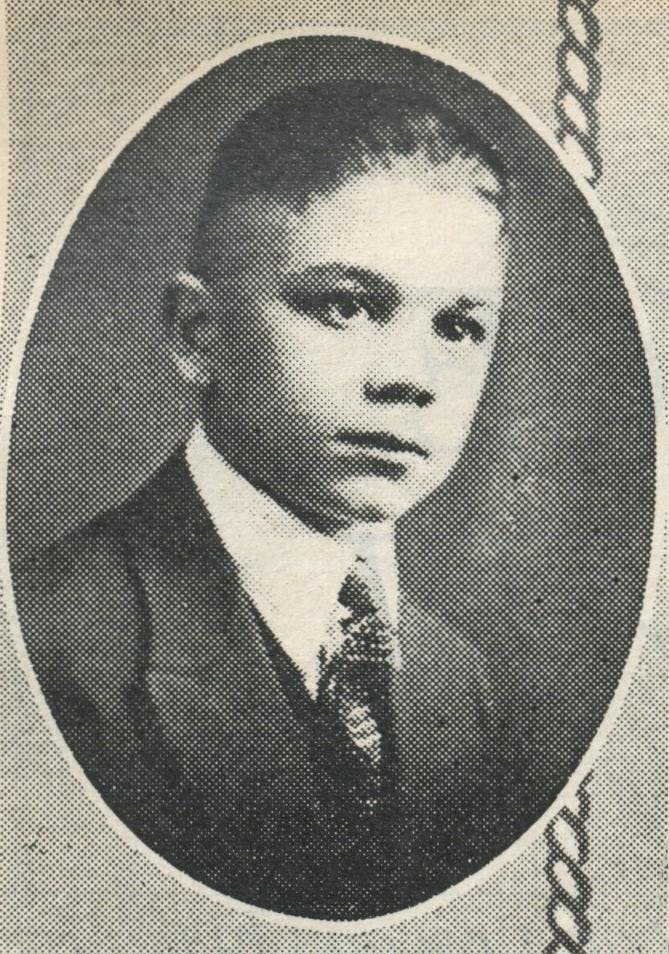

For Leon Jaworski, conscience and ambition have always been united in a single figure: his father. A Polish immigrant and Evangelical minister, the Reverend Hannibal Jaworski had an excellent European education, spoke seven languages, mastered a variety of musical instruments, and could deliver a back-straightening Sunday sermon. After Leon’s mother died in 1909 when he was three years old, Reverend Jaworski brought his four children back to Waco from the South Texas town of Geronimo.

Jaworski grew up, as he put it, “on the wrong side of the tracks, the south side.” Being fairly close to the holy spires of Baylor University, the neighborhood was by no means a slum, but most of its residents were working-class and low-income people. For the Jaworski children, English was the equivalent of a second language. At home, they spoke German, the language of Leon’s Viennese mother and the tongue in which Leon’s father delivered his Sunday sermons at his church at 701 South Eighth Street. Because of their foreign name and thick accents, the Jaworskis sometimes were the recipients of cruel jokes and taunts, especially during World War I, when anti-German and anti-immigrant fervor ran high among Waco’s Bible Belters.

True to their father’s urging to “achieve,” the Jaworski children all set their sights on entering a profession, preferably one that paid better than the ministry, and raced to get there. They were not ashamed of their father’s occupation or lack of wealth, but they also remembered the hardships and aspired to comfort and financial security. For most of his youth, Leon wanted to become a doctor and open a practice with his older brother. But he showed such an inclination to speak up for his friends and classmates that, as his brother Hannibal recalls, “He was always being elected class president or class defender.” In his junior year he entered the high school debating match and won. The next year he won again. These victories proved to be the first of many crossroads in his life.

“Things were a little bit different after that,” Jaworski remembers. “I was accepted a little bit more by the students at Waco High School, and I had a chance to rub elbows with kids from some of the more prominent families.”

Jaworski also changed his mind about becoming a doctor. Now he raced to become a lawyer, an even more exciting profession in which to do good and, at the same time, do well. Although he had skipped a grade and was only fifteen when he graduated from high school, Leon spent just one year as an undergraduate at Baylor, then sought admission to the law school. When the dean told him he was too young, Jaworski went right to the university president, showed him his consistently outstanding scholastic record, and won special permission to enroll. Three years later, at the age of nineteen, Jaworski graduated from Baylor Law School, petitioned to remove his disabilities as a minor, and became the youngest lawyer in Texas history.

While following his ambition, Jaworski did not neglect his religion. All through high school and college, he remained active in his father’s church, where he and his brothers and sisters sang in the choir. As in all other endeavors, Leon aspired to the top position—in this case, the role of minister. (Some would say God.) One of the high points of the year came each spring, when his father would give young Leon the pulpit for the Mother’s Day address, a sermon Leon still remembers as a “real tear-jerker.” Later, when he was pursuing his master of court degree at George Washington University, Leon continued preaching, often traveling out to the country towns of Maryland to spell the pastors of the local Evangelical churches.

After getting his master’s, Leon returned to Waco and went to work for a prominent local attorney named Tom Scott. Waco still had a reputation in those days as “Six-shooter Junction,” so there were always murderers to defend and victims to represent. Those were also the days of Prohibition, and, while the town’s many Baptists disdained alcohol, the citizens of the nearby Czech and German communities were not to be denied their beer. Himself a fan of good home brew, Leon defended several moonshiners and bootleggers.

Although Leon did not win every time, he did well enough that the other attorneys in town suggested he had some sort of in with the judge. He claims he simply worked harder than most and prepared his cases with exceptional thoroughness. His friends say he also had an uncanny ability to intuit what the law should be even in situations where he had not read the statutes. “Leon was just a natural-born lawyer,” observes University of Texas Regent Edward Clark, a longtime friend and fellow attorney who knew him later. “Going to law school only confirmed it.”

In addition to this inborn lawyerliness, Leon had an astute grasp of what he called “everyday garden-variety psychology.” On one oft-reported occasion, he came to court with a stiletto in his pocket, walked over to the jury box, looked one of the jurors right in the eye, and said, “If you’re going to send this man to the electric chair, you might just as well walk right over there and stab him.” Then, he reached into his pocket and handed the juror the stiletto. “That man didn’t even want to touch it,” Leon recalled years afterward. “I thought he was going to faint.”

Appropriately enough, Jaworski first made a name for himself not as a private practitioner but as a court-appointed public defender in the Jordan Scott murder case of 1929. Jaworski eventually lost the case, but, despite overwhelmingly adverse evidence and his indigent client’s incriminating changes in testimony, he put on such a spectacular and unflagging defense that the local newspapers carried the story of the trial in long play-by-play accounts.

Out of that experience came a lesson Jaworski took to heart: dedication to conscience could further his ambition. Through prominent Waco attorneys Frank and Jake Tirey, Leon’s work in the Jordan Scott case came to the attention of a Houston attorney named A. D. Dyess. Dyess was then looking for a young trial lawyer to help him with his appellate work and he offered the job to Leon. With his friends and law partners urging him not to fall back on an easy career in Waco, Jaworski quickly accepted and packed his bags for Houston.

Shortly after his arrival, however, Jaworski’s career took another propitious turn. In his first case in the old Galveston Court of Appeals, the 24-year-old golden boy from Waco was pitted against two name partners in his future law firm, John Freeman and Colonel William B. Bates of the already prominent Fulbright, Crooker, Freeman, and Bates. Appropriately, the case involved the law firm’s biggest client, Anderson, Clayton and Company, and the question of whether one of A. D. Dyess’ clients owed the giant cotton conglomerate a certain sum of money. Freeman and Bates naturally scoffed at their adversary’s apparent youth and inexperience, but, charged by their insults, Jaworski proceeded to win the case.

Freeman and Bates were impressed. About a year later, after Jaworski continued to accrue victories for A. D. Dyess, Freeman offered him a well-paying job. It was an offer any other 25-year-old trial lawyer in Texas would have found impossible to refuse, but Jaworski was coy and kept putting Freeman off. Finally, Freeman took him in to see founding partner John Crooker, Sr.

“What the hell’s the matter with you?” Crooker raged in his usual straightforward fashion. “Any lawyer in Houston would give anything to join our law firm, but you keep fartin’ around.”

Jaworski did not waver. “Mr. Crooker,” he said. “You’ve got two fair-haired boys here already, and they both have strong family connections. I don’t know anybody and I don’t want to go up against that. I can’t bring you any business.”

“Listen,” Crooker retorted, “we don’t need anyone to bring us business. We need somebody to attend to it.” A few days later, Jaworski left A. D. Dyess and went to work for the men whose law firm would one day become more famous for his name than for theirs. In 1935, at the age of 29, he became the firm’s youngest partner.

Watching Jaworski and listening to the changes in his voice as he recalled his early days at the firm was one of the most remarkable moments in our series of interviews.

“When I came to work, I started trying lawsuits,” he had begun, with his voice slowly rising. “And I mean I tried one right after the other. All kinds. You can’t name a type of lawsuit I didn’t try. And . . . this . . . this is the part that’s hard to tell . . . I didn’t lose a lawsuit. You see, my trials were mostly jury trials, and I just won ’em. I worked like a son of a bitch. I worked at nights. I got my cases prepared. I knew what I was doing. And the reason I escalated as I did is because I just didn’t lose any cases. They gave me cases that no man should even try. This is right. I could tell you stories about how I went to Beeville and offered all kinds of money to settle this lawsuit, but they wouldn’t take it, and I turned around and won the case.”

Jaworski suddenly realized that his voice was high enough to shatter glass. He smiled weakly, seemingly embarrassed and somewhat saddened by the force and enthusiasm of his own reminiscences, then continued in a lowered tone.

“All I’m saying is that I worked hard,” he said. “I can’t talk about these things, because people would think I was bragging. But the truth of it is, I went for years and years and years without losing a lawsuit—certainly up until World War II.”

Despite his success, Jaworski remained an outsider to Houston society for many years. In 1931, shortly after joining Fulbright, Crooker, he married Jeannette Adam, a Waco sweetheart who played the organ in his father’s church, but neither his new bride nor his courtroom victories provided the sort of “family connections” he had feared he would need to succeed in his prestigious new law firm. Houston in the thirties was still an overgrown antebellum town run by one man, Jesse H. Jones. Future leaders like George and Herman Brown of Brown & Root and Texas Eastern hadn’t yet arrived. The great oil families were still in the infancy of their wealth, and neither the older new rich nor the newer new rich of the day was especially cosmopolitan. To them Leon Jaworski was just another trial lawyer with a funny name.

In discussing this period with Jaworski, I was struck by how sharply this early social exclusion affected him and how ambivalent he has become about it. “In the early years of my professional life, my greatest experience in life was to get these people to like me,” he confided at one point. “For me to find a way of working into their embrace, where they cared for me, where they were friendly, was the greatest thing I could do… It was the same with witnesses. If I could just sit down with them, I could usually win them over. In the later stages, I would still try to do it, but I couldn’t always take the time.”

But, while one side of him craved popularity, another side disclaimed its importance. Indeed, in almost the same breath in which he told how important it was for people to like him, Jaworski went on to claim that he “never really gave a damn” about social acceptance. “I just wanted to do my job,” he said. “I didn’t let it bother me.” Then he added wryly, “All I know is that I’ve got too many invitations now.”

When World War II broke out, Jaworski, then 35, was exempt from the draft. Unlike many men his age, he did not choose to enlist in the U.S. combat forces, but, claiming his patriotism prevented him from sitting on the sidelines, decided to join the Judge Advocate General corps, the military equivalent of an in-house law firm and prosecution force rolled into one. Jaworski started out trying top-secret cases of German POWs charged with committing crimes while in U.S. detention camps. Then, as the war drew to a close, Washington sent him overseas, where he became chief prosecutor in the first set of war crimes trials after the war. Contrary to popular misinformation, these were not the proceedings at Nuremberg, but a separate and earlier set of prosecutions that were run solely by the U.S. Army and involved, among others, the men who had supervised the death camp at Dachau.

Later Jaworski declined the opportunity to prosecute the Nuremberg trials, in part because his father was then ill and dying, and in part because he disliked the judicial hodgepodge of French, Russian, and U.S. law. He also felt the trials involved too many purely military offenses. “I didn’t like making a war crime out of an act of aggression,” he told me. “That bothered me to no end.”

Jaworski added that he had had some misgivings about his role in the earlier war crimes trials. Who could blame him? After all, compared to events like the Normandy invasion, it hardly seemed a great feat to convict a group of admitted Nazis before an American tribunal and a war-shocked German jury. Nevertheless, Jaworski’s exploits garnered him the Legion of Merit, not to mention a considerable amount of stateside publicity, and, until Watergate, ranked as his own proudest achievement. Ever after, he preferred for friends and associates to call him “Colonel.”

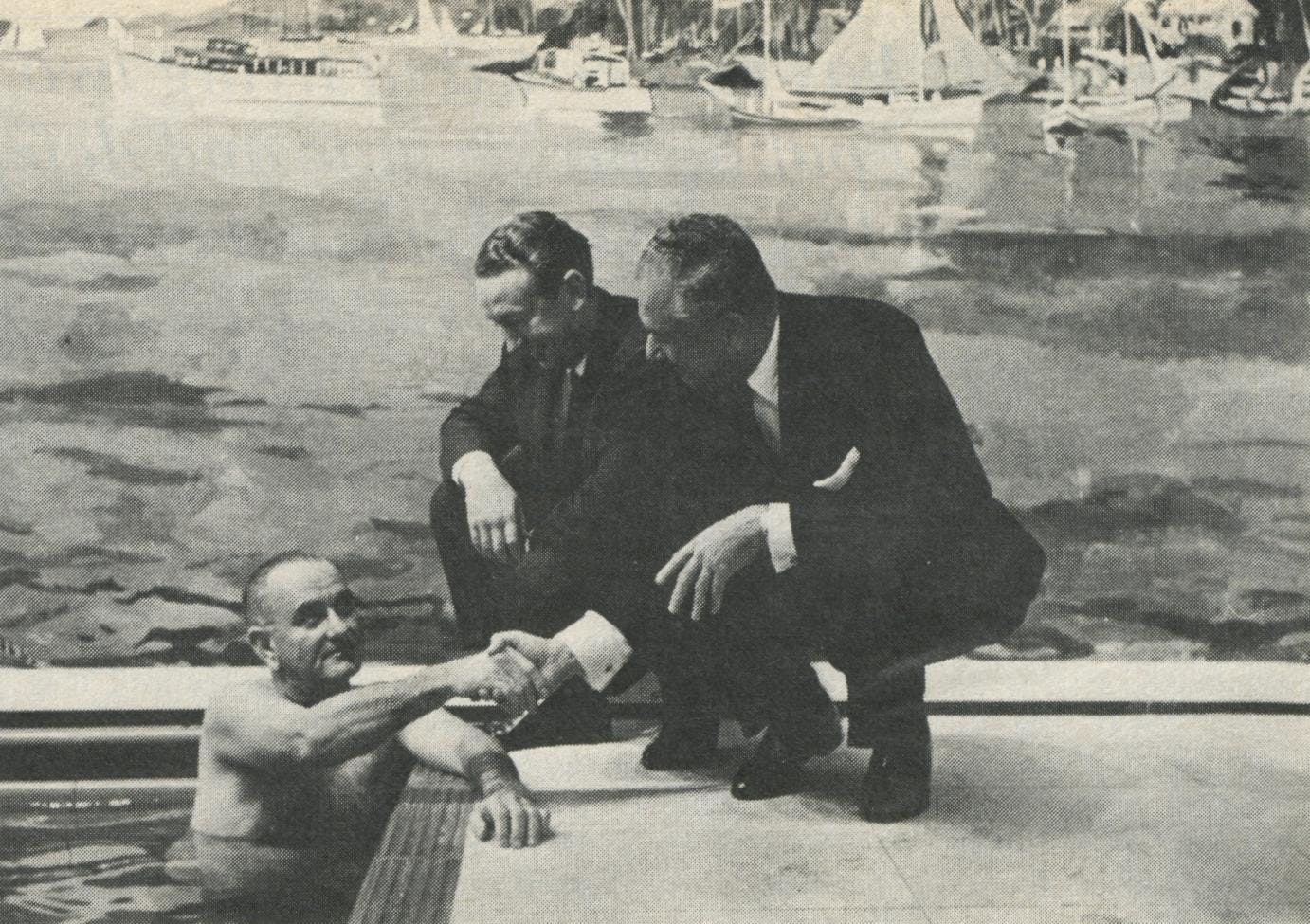

The war crimes trials proved to be another instance in which Jaworski’s willingness to perform a public service not only satisfied his conscience but also furthered his professional ambitions. Returning to Houston something of a hero, Jaworski was feted and honored and his name was added to the name of his law firm. Then, after a frustrating lull, he began trying lawsuits again. By now, Jaworski’s clients were not moonshiners or indigent murderers, but some of the state’s richest families and some of the country’s biggest corporations, and he found it even harder to satisfy his conscience while following his ambition.

Part of the difficulty stemmed from the nature of the business world Jaworski reentered. Like the partners in several other big Houston law firms, the partners in Fulbright, Crooker came to dominate an independent network of banks, foundations, and corporate clients, which together formed a very real power base. Backed by the strength of this institutional framework, Fulbright, Crooker quadrupled in size after World War II. By the mid-seventies, the firm had over 250 lawyers and ranked as one of the five largest in the country. This growth did not come about by magic. Although Houston’s boom economy insured plenty of business to go around, law firms like Fulbright, Crooker and Vinson & Elkins and Baker & Botts were always highly competitive. Often, they sought after the same prized corporate clients; at other times, competing corporations sought representation by the same firm. They all cajoled and stroked and flirted with each other’s clients. They all worked hard to increase their political influence by making big campaign contributions to candidates in both major parties. “Nice” lawyers seldom came out on top.

In the early fifties, Jaworski was his firm’s chief legal war-horse. He defended Anderson, Clayton in a series of major antitrust suits on the West Coast. Then, he went to Miami to defend Florida Power & Light in another set of antitrust cases. Back home, he represented the likes of Conoco chairman L. F. McCollum, Lincoln Liberty Life Insurance president (and later U.S. Senator) Lloyd Bentsen, Texaco heirs Joe and Craig Cullinan, and oilman J. R. Parten. He helped the Bank of the Southwest weather an earlier Sharpstown banking scandal and found time to help a few would-be corporate powers get their start; one was Joe Albritton, then a young banker and now publisher of the Washington Star.

Jaworski’s biggest case of the period, the one that really cemented his reputation in Houston, never even went to trial. This was the so-called Moody will case, in which Jaworski negotiated an $8 million out-of-court settlement for his client, Mrs. Libby Moody Thompson, who was the wife of then Congressman Clark Thompson and the daughter of Mrs. W. L. Moody of the wealthy Galveston insurance family. In the process, Jaworski also collected $1 million, the largest single fee in his law firm’s history. Normally, most of Jaworski’s fee would have gone to the profit pool shared by the senior partners. However, Jaworski insisted that the $1 million be split among all the members of the firm.

“I was probably busier than I should have been,” Jaworski admitted. “I was always fearful that I might drop the ball someday . . . because I would not be prepared . . . because of the pressure of things.” Actually, there was little chance of that. By the postwar years, Jaworski was representing his clients with over a quarter century of legal experience, and, according to friends who knew him then, could probably have carried most cases off on the strength of his courtroom style alone.

“He always had this remarkable ability to put on the appearance of the ‘reasonable man’ in the ‘reasonable man’ test,” remembers one former associate. (The pivotal point of many lawsuits is how the jury decides a “reasonable man” would have acted under the circumstances.) “He would never really seem to attack a witness or raise his voice to make a point. He was always very, very gentlemanly in his approach. He would reason with them and try to show them that the only real alternative was the one he had in mind all along.”

Inside, of course, Jaworski’s mind was churning. “He always spent a lot of time psyching up for a case,” recalls his friend and business associate A. G. McNeese. “It was very important for him to be convinced that his client was right, but once he had convinced himself, nothing could stop him.”

Meanwhile, Jaworski’s relationship to his big corporate clients underwent an important change. Besides merely representing them, he soon became personally identified with them, as well as partly accountable for their operations, by joining their boards of directors. At the same time, Jaworski gradually replaced his aging partners as the leader of his law firm and of the firm’s power base. If Jaworski had spent the rest of his life as a big-time corporate lawyer, these new associations would have seemed no more than a matter of course, a natural step in the progression of his business ambitions. However, as he began to assume the role of America’s premier man of conscience, his dealings in the less than conscientious world of big banks and corporations came under increasing scrutiny and public criticism. This was especially true of Jaworski’s roles in the web of interlocking boards of directors supervised by his law partners.

To outsiders, this all seemed like a game of real-life Monopoly being played on Fulbright, Crooker’s private conference table. Though they had ties to major financial institutions throughout the state, the partners in Fulbright, Crooker had their closest and most lucrative relationship with Bank of the Southwest. In addition to serving as the bank’s legal counsel, members of the firm dominated the board of directors and occupied the top executive positions. Together, the bank and the law firm grew in size and prominence. The bank brought the law firm business from depositors and big borrowers, and the law firm referred clients to the bank. Members of the law firm used the bank for their own personal finances and could be sure of a ready source of credit, thus using this cozy relationship to help build their own fortunes.

Fulbright, Crooker partners (or former partners) also occupied all four positions on the board of trustees of the multimillion-dollar M. D. Anderson Foundation, an institution that often served as their own private backup bank. Established by the same cotton merchant who founded Anderson, Clayton, the Anderson Foundation was created for the purpose of giving money to charities, particularly medical ones. Its trustees saw that this purpose was carried out, but they were very selective about where they channeled their largess. Between 1936 and 1976, the Anderson Foundation gave some $11 million in contributions to the Texas Medical Center and another $51 million to various other philanthropic organizations. Among the principal beneficiaries were Baylor Medical School (yet another Fulbright, Crooker client whose board of trustees includes Baylor alumnus Leon Jaworski) and the State Bar of Texas’ new building fund. A number of buildings, wings, and professorships at Baylor Medical School and Baylor Law School are named for Jaworski and other present and former Anderson Foundation trustees; the plaza at the new State Bar building is named for Leon Jaworski.

In addition to giving money away, the trustees were also responsible for investing the foundation’s endowment in profitable ways. Like other foundations, the Anderson Foundation put a great deal of money in blue-chip stocks; not surprisingly, one of its favorites was Bank of the Southwest, where it was the largest single stockholder. But unlike many other foundations, it actually made most of its money by lending it like a bank. Among its principal borrowers were partners in Fulbright, Crooker and their friends and associates. The amounts of these loans ranged from a few thousand dollars to half a million. According to the Anderson Foundation’s indenture, which had been drawn up by Fulbright, Crooker, the trustees were even permitted to make loans to themselves while they served on the board of trustees. In practice, however, they seldom used this privilege. The typical pattern was the one Jaworski followed. In the early fifties, he took out a $40,000 loan from the Anderson Foundation, then, upon joining the board of trustees in 1957 repaid his loan by transferring his debt to Bank of the Southwest, never borrowing from the foundation again.

Like their predecessors, Jaworski and his fellow trustees carefully perpetuated Fulbright, Crooker’s dominance of these institutions by filling vacancies on their boards with other members of the law firm. Thus, after joining the boards of the Anderson Foundation and Bank of the Southwest in the fifties, Jaworski went on to become president of the foundation and chairman of the board of Southwest Bancshares, the Bank of the Southwest’s parent holding company. It was an arrangement ideally suited to Jaworski’s ambition and his sense of conscience. For by virtue of their positions, Jaworski and his associates were able to enjoy much of the power, prestige, and perquisites of great wealth—including the power to help and reward their friends (and indirectly themselves) through the disposition of loans and grants—without having to pursue wealth with unseemly eagerness and avarice.

Though outsiders have often questioned these interlocking relationships, they are neither illegal nor peculiar to partners in Fulbright, Crooker. Vinson & Elkins, for example, has maintained a similar law firm/bank relationship with First City National Bank to the advantage of both. However, in a 1969 tax reform law, Congress took a step toward limiting the powers of foundation trustees by prohibiting so-called “insider” loans from a foundation to borrowers with close business ties to members of the board of trustees.

In discussing this subject, Jaworski was extremely defensive about the Anderson Foundation’s pre-1969 lending policies, quickly pointing out that every loan the foundation made was checked out by First City National Bank, which acts as the foundation’s agent. He shrugged off any suggestion that the foundation’s “insider” loans represented a power to reward friends, associates, and other private individuals that should have been restrained. “All the loans were good, bankable loans, and the Anderson Foundation never lost a penny,” he said. “That’s the test.” Jaworski added that after the 1969 reforms, the foundation did not make any more “insider” loans. Nevertheless, Jaworski’s critics would continue to raise questions about his lending policies on the Anderson Foundation board both before and after Watergate, chiefly because one of the pre-1969 loans he approved was $850,000 borrowed by former LBJ adviser Jake Jacobsen, the man who later testified against John Connally.

There can be little doubt that political considerations entered into the transaction, Jacobsen and his partner Ray Cowan used the money to buy stock in three Texas savings and loans. But, at the time, many Texas businessmen assumed that they were simply acting as front men for President Johnson. Jaworski apparently had the same impression.

“I’ve forgotten the details of it exactly—whether Lyndon first talked to me about it or whether it was Jake,” Jaworski explained. “But it was a matter that I thought had the complete approbation of Johnson.”

Jacobsen and Johnson, however, fell into an argument over who owned the stock shortly after LBJ left office. Jacobsen managed to hold onto the stock, then paid off his loan to the Anderson Foundation in the early seventies by refinancing his stock purchases through the City Bank & Trust of Dallas. Later, Jacobsen and Cowan attempted to pay off their loans from City Bank & Trust with bad checks and were indicted on related charges of embezzling the savings and loan associations. Although Cowan was convicted of the embezzlement, Jacobsen convinced the Justice Department to drop the charges against him in return for his testimony against John Connally in Connally’s bribery trial. Using the Anderson Foundation loan to link Jacobsen with Jaworski, Connally’s supporters later started rumors insinuating that the two had somehow conspired to smear Connally. The rumors spread quickly throughout Texas establishment circles, dividing many longtime friends of both Connally and Jaworski, but they were never substantiated.

Naturally Jaworski could not rise as high as he has without making enemies of people he did not even know. As the lead partner in his firm, Jaworski was saddled (sometimes unfairly) with responsibility for cases he was not personally involved in and was held accountable for the overall reputation of his firm. In many quarters, that reputation included allegations of conflicts of interest and other improprieties stemming from cases like the highly publicized and very bitter Andrau estate battle of the early seventies. The Fulbright, Crooker-dominated Bank of the Southwest was accused of robbing the trust funds of the Andrau heirs. After losing a $9 million judgment in a Louisiana court, the largest such judgment in the state’s history, the bank eventually agreed to an undisclosed out-of-court settlement believed to be in the millions. Though Jaworski claimed not to be personally involved in either the actions of the bank’s trust department or the firm’s handling of the lawsuit, the Andrau heirs nevertheless blamed him and the other top men in Fulbright, Crooker and Bank of the Southwest for attempting to siphon away their inheritance.

Despite his claims of good intentions, Jaworski suffered through a number of his own controversies as well. His bitterest and most widely questioned battle of the sixties was the fight over the $110 million Robert A. Welch Foundation, which pitted him against some of his Houston legal establishment peers. The case began with Jaworski representing three of the foundation’s trustees in their attempt to remove the fourth trustee because of various incompatibilities. But after a controversial series of events involving a proposed settlement, the trustees fell to fighting among themselves again, and two of them hired Jaworski as their legal counsel. Suddenly he found himself representing one set of longtime clients against another set of longtime clients. Jaworski also claimed that under the proposed settlement, he should have been appointed to the board of trustees, maintaining that his appointment was consistent with the “public’s interest” in preserving the foundation’s assets. To make matters worse, Judge Arthur Lesher abruptly decided to settle the matter by upholding Jaworski’s appointment to the board, and entered his decision without notice or hearing on a Saturday morning.

By this time, the Welch Foundation battle had escalated into a power play involving lawyers from four of Houston’s largest law firms, among them Jack Binion of Butler, Binion, Rice, Cook & Knapp, who had himself been named to the foundation’s board, and Dillon Anderson and Frank Harmon of Baker & Botts, who represented one of the foundation’s trustees. Anderson and Harmon quickly filed a motion to disqualify Jaworski from representing one set of former clients against the other. Alleging that Jaworski had “conceived a ‘public’ justification for his actions’’ only for the purpose of pursuing “his own candidacy for trustee,” they also asked the court to remove him from the foundation’s board. After three years of vicious allegations and a trip up to the court of civil appeals, Jaworski finally agreed to step down from the foundation’s board in favor of Houston oilman Jack Josey, and all the parties dropped their claims and counterclaims.

Unfortunately, that did not exactly end things. “Quite a few people in town believed that Jaworski was trying to muscle his way into control of the foundation,” said one Houston attorney who observed but did not participate in the battle. “Most good attorneys don’t carry their animosity outside of the courtroom for very long. In fact, aside from winning, there’s nothing you appreciate more than being beaten by someone who is clever and can do it fair and square. But I know for a fact that Jack Binion and Dillon Anderson and Frank Harmon stayed mad at Jaworski for a long time after that was over and for all intents and purposes their clients are the ones who won.”

Like other big-firm partners, Jaworski also proved he was not above accepting corporate clients with less than spotless reputations. Perhaps his most controversial legal/business deal was his decision to represent the already embattled Oscar Wyatt and his Coastal States Gas Producing Company. As Jaworski remembers, Wyatt simply came to him one day and said, “Leon, I want to give Coastal States’ business to your law firm, but there are certain situations in which I want you to be personally available to me.” Jaworski agreed, but with the proviso that he would have to pass on each one of the “situations” individually.

There was only one problem. At the time Wyatt approached him, Jaworski’s firm was representing Coastal’s very reputable competitor, Houston Natural Gas. Jaworski informed HNG president Joe Foy of his new client and asked Foy what he wanted to do. Foy agreed to keep HNG’s business with Jaworski’s firm to see if the potentially contradictory relationship would work in actual practice. After a few months, Foy decided to move HNG’s business to Vinson & Elkins.

All this worked to the advantage of Jaworski’s law firm. If losing HNG meant losing a respected client, it did not mean losing much legal business. Foy, an attorney as well as an engineer, had built up a substantial in-house legal staff at HNG and farmed out only a small portion of the company’s legal work. Coastal States, on the other hand, gave most of its work to its outside counsel. The company also had a long history of litigation, and was on the verge of having a great deal more when its Lo-Vaca municipal gas supply subsidiary began to teeter on the brink of bankruptcy, precipitating the biggest energy supply scandal in Texas history. “I remember thinking to myself when Leon did that, ‘No one is going to make more money than Fulbright, Crooker,’ ” recalls Ed Clark. “I don’t know how much Coastal States brought into that firm in legal fees, but it has to be up in the millions. I’m sure they’ve given that firm fifteen or twenty times the amount of work HNG would have brought in.”

In August of 1971, Jaworski increased his personal involvement with Coastal States by joining the company’s board of directors. Because of the litigation pending against Coastal States and Lo-Vaca, Jaworski declined to discuss the subject beyond what is already on the public record. However, sources close to him in his law firm maintained that Jaworski sometimes took credit for “saving” Oscar Wyatt and his beleaguered enterprise by helping to frame a 1973 agreement separating Coastal States from Lo-Vaca. Under the agreement, Lo-Vaca was placed in a quasi-receivership, where it was left to struggle with the problem of finding enough gas to supply its customers in Austin, San Antonio, and the Lower Colorado River Authority without help from its corporate parent. Meanwhile, as utility bills of millions of Texans skyrocketed, Coastal went on to become one of the ten largest corporations in the state.

Apparently, Jaworski considered his actions on behalf of his client another instance of public duty. “Jaworski felt that unless Coastal States was saved, there would be a debacle—not just for the company but for all the cities who bought gas from Wyatt,” said a lawyer in Jaworski’s firm.

Critics of Coastal States and Lo-Vaca do not see Jaworski’s actions as being nearly so public-spirited. According to minutes of Coastal States board meetings on file with the Texas Railroad Commission in Austin, it was Jaworski’s firm—with director Jaworski in explicit concurrence—that denied San Antonio’s request to audit Lo-Vaca’s reserves in January 1972 when the city became concerned (legitimately, as it turned out) that Lo-Vaca did not have enough gas to supply its contracts.

Later, it was director Jaworski who moved in a December 1972 board meeting to sell off $5 million in Lo-Vaca reserves, or about twenty days’ worth of gas. The motion came nearly two weeks after San Antonio was hit with the first of several major gas curtailments, and its citizens were up in arms. Critics of the sale characterized it as an effort by the parent Coastal States to “loot” the assets of its ill-fated subsidiary before casting it adrift.

Jaworski’s associates maintain that all of Jaworski’s motions on the board were made with “good faith” confidence in Wyatt and in the recommendations of other Fulbright, Crooker partners. In the rarefied air of high corporate finance, one trusted one’s friends. These sources also pointed to a 1973 memorandum from Fulbright, Crooker partner Uriel Dutton to the SEC, in which Dutton said that the $5 million sale of Lo-Vaca reserves was actually part of a larger “trade-off” deal whereby Lo-Vaca obtained the rights to other gas reserves and ultimately increased its total gas supplies. Whatever the case, it is clear that just as in Watergate, Jaworski’s basically conservative instincts guided his actions to preserve the institution involved, whether it was the presidency of the United States or a corporation caught bilking millions of Texas consumers.

While Jaworski may have pursued most of his firm’s business with a clear conscience, his conscience often drew the line on personal business opportunities. “Leon passed up plenty of chances to make a lot of money just because he didn’t feel right about it,” observes Ed Clark. “That’s just the way he is. Beyond the point of making his family comfortable, money just doesn’t interest him that much.”

That may be overstating things a bit—Jaworski does have a salary in excess of $200,000 a year, he has acquired a house in River Oaks and a 800-acre ranch near Wimberley, and he has accumulated over $375,000 worth of stock in Bank of the Southwest and Anderson, Clayton. But he never attained the sort of wealth John Connally and other prominent Texans acquired in the fifties and sixties. In fact, while admitting that he is a millionaire, Jaworski insisted in our interview that even today his net worth remains “way below” $5 million.

Although he channeled most of his philanthropic energies through his role on the Anderson Foundation board, Jaworski also made large personal contributions to organizations ranging from the First Presbyterian Church, of which he is an elder, to the Houston Symphony. In 1969, he and his wife endowed the Leon Jaworski Foundation with $125,000 and dedicated it primarily to the encouragement of legal scholarship. Jaworski later assigned the foundation the royalties from his bestselling The Right and the Power, a move that promises to increase its assets by over $500,000. One of the foundation’s principal gifts has been a contribution establishing a Leon Jaworski chair at Baylor Law School.

Both personally and professionally, Leon Jaworski was always more concerned with status—power and prestige, recognition and reputation—than with money. It was not just a matter of ego. Jaworski wanted to make his mark, express his views, but he also genuinely wanted people to like and respect him. He still strove for acceptance. With the backing of his law firm’s large voting bloc, Jaworski wound up the decade of the fifties by running for and winning the presidency of the State Bar. In 1960, the year of his tenure in office, Jaworski published his memoir of the war crimes trials, After Fifteen Years. The book was full of ringing moralistic phrases taken straight from his father’s sermons back in Waco. “When the masses of any nation flout God’s commandments; when His divine teachings of love among neighbors, and brotherly regard for fellowman yield to practices of hatred and cruelty,” Jaworski wrote, “dire consequences are certain to follow. Germany is not the first nation in history to learn this lesson, but Germany’s experience is one of modern times.”

In 1961, Jaworski also published in the state bar journal an article entitled, “The Unpopular Cause,” in which he exhorted his professional colleagues not to shrink from defending the constitutional rights of controversial clients. Jaworski is neither a liberal nor an intellectual, but this article stated the essentials of his personal philosophy: the classical lawyer’s notion of the primacy of institutionalized rights and liberties.

Against considerable odds, Jaworski did attempt to practice what he preached. Through most of the sixties and early seventies, he shuttled constantly between his private practice in Houston and some news-making role as a specially appointed public prosecutor, defender, or spokesman-advocate. In some instances, his activities had all sorts of political overtones; in others, they appeared to be public relations for his law firm. But Jaworski always preferred to see his “assignments” purely as forms of “public service,” pointing out that he was usually sought for the job, not the other way around.

Many times, Jaworski played the undisputed role of good guy. His most famous case was his prosecution of Mississippi’s segregationist Governor Ross Barnett for disobeying a court order to let blacks enroll in the University of Mississippi. It was also his most courageous. “His clients were calling up and telling him they were going to take away their business,” recalls Jaworski’s brother Hannibal. “People called him a ‘nigger lover.’ ” Undeterred, Jaworski pursued Barnett until he capitulated before the Supreme Court. “After that,” Jaworski told me with a grin, “the same people who said they were going to take their business away were in here begging me to represent them. One man even got down on the floor.”

Later, Jaworski’s stints in public service included acting as a special assistant attorney general of Texas in the Billie Sol Estes case and in the State of Texas’ fight to uphold the Legislature’s 1970 redistricting plan. Both times he appeared before the Supreme Court, losing the first case and winning the second.

Within the closed corridors of his law firm, Jaworski also attempted to exert moral leadership. He encouraged his associates to perform pro bono work (something most big Houston firms simply did not do) and set the example himself by defending a black indigent client simply because the man told the judge he wanted his court-appointed attorney to be the great Mr. Leon Jaworski. In the mid-sixties, Jaworski also persuaded his partners to take the lead among Houston’s big firms in opening their doors to talented young Jewish lawyers.

Still, many of Jaworski’s public actions and attempts at moral leadership were fraught with controversy and apparent contradictions. For example, about the same time he was prosecuting Ross Barnett, Jaworski was also defending University of Texas regents in their fight to keep black students out of dormitories and “extracurricular activities” on the UT campus. In 1966, after a three-year court battle, the regents finally agreed to comply with the black students’ demands.

Today, Jaworski claims that he agreed to represent the regents because it was a “very touchy situation which could have exploded at any time . . . the Legislature was threatening to cut off funds.” He says the eventual settlement of the case was the one he had in mind all along. “We knew how we were going to move the chessmen around,” he says. “But we knew that if you tried to do it precipitously, you had a problem on your hands.”

Sam Houston Clinton, who represented the black students, does not remember it quite that way. “As I recall, Jaworski talked about everything but a settlement and fought damn hard all the way,” Clinton says. “If all he wanted was the settlement that gave us what we were asking for in the first place, why did it take him three years to make up his mind?”

Jaworski’s role in the Billie Sol Estes case that reached the Supreme Court also provoked contention, this time in the form of allegations of conflict of interest. The issue before the high court was the ostensibly narrow question of whether the presence of television cameras in the courtroom during one of Estes’ Texas trials had prejudiced the jury. (Jaworski said it did not.) However, at the same time Jaworski was acting against Estes in Washington, his Texas law firm was representing a company called Commercial Solvents, which happened to be a codefendant with Estes in another case related to the West Texas swindler’s famous fertilizer fraud. Still a third related case involved Estes, Commercial Solvents, and attorneys in Jaworski’s law firm. After a heated exchange of letters, Estes’ attorney, the late John Cofer of Austin, finally decided not to move to disqualify Jaworski, in part because of his past admiration for him, and went on to beat him in the Supreme Court.

In most of his public actions, Jaworski has tried to keep himself above petty partisan issues and party politics. He has never run for public office and generally leaves the details of political fund raising and campaign contributing to his associates. Jaworski prefers to enter the public arena only when his participation can be justified on broad civic grounds. Thus, he took pride in his role in building public support for the construction of the Astrodome and in promoting the passage of several municipal improvement bonds, as well as in the work he did on the ill-fated Texas state Constitutional Revision Commission. Always, Jaworski has favored the most conservative, most establishment side of the issue, whether it is the question of selecting state judges (he favors appointment over popular election) or the development of downtown Houston (he is naturally for it). In fact, in his first big case of the sixties, Jaworski agreed to defend Lyndon Johnson’s assertion of the right to run for both vice president and U.S. senator in the 1960 election. Once again, Jaworski appeared before the Supreme Court and won. Jaworski later claimed that LBJ offered to nominate him to the Supreme Court or to the Office of Attorney General. Several former LBJ insiders deny that Johnson ever seriously considered him for the high court or for attorney general, but they confirm that LBJ offered Jaworski other federal appointments, which he always refused. (“I wanted to be independent,” Jaworski explained later. “If I had taken one of those positions, I would have had to do what Johnson told me.”) However, Jaworski did agree to serve on five presidential commissions, including the Commission on Crime and Violence, and assisted Texas Attorney General Waggoner Carr in keeping LBJ informed of the status of the Texas-based investigation of the Kennedy assassination.

Starting in 1965, Jaworski also served on Governor John Connally’s Public Education Committee. Contrary to later suppositions, he and Connally were not close friends. In fact, Jaworski had supported Connally’s opponent, fellow Baylor alumnus Price Daniel, Sr., in the 1962 gubernatorial primary. However, at the time, both men shared a mutual respect as well as a common devotion to LBJ.

Despite his various scrapes and controversies in the sixties and seventies, Jaworski continued to gain professional recognition, including election to the elite American College of Trial Lawyers, his most prized professional association. He also became active in the American Bar Association, and, with the help of law partner Gibson Gayle, the perennial ABA secretary, he leapfrogged over the usual obstacles to win the ABA presidency.

By the end of the sixties, Jaworski had also gained entrance to the highest Texas establishment circle—that select group of power moguls, bankers, lawyers, and industrialists who met in George Brown’s Suite 8F in Houston’s Lamar Hotel. For the outsider with the funny name this was the final sign of acceptance. Though Jaworski says he did not attend every meeting of the 8F Crowd, he was clearly impressed by the likes of George Brown and Gus Wortham and their skills in what he considered a chess game of power, politics, and business. “As a matter of fact,” he told me, “it was at the 8F that Lloyd Bentsen was selected to be United States senator.”

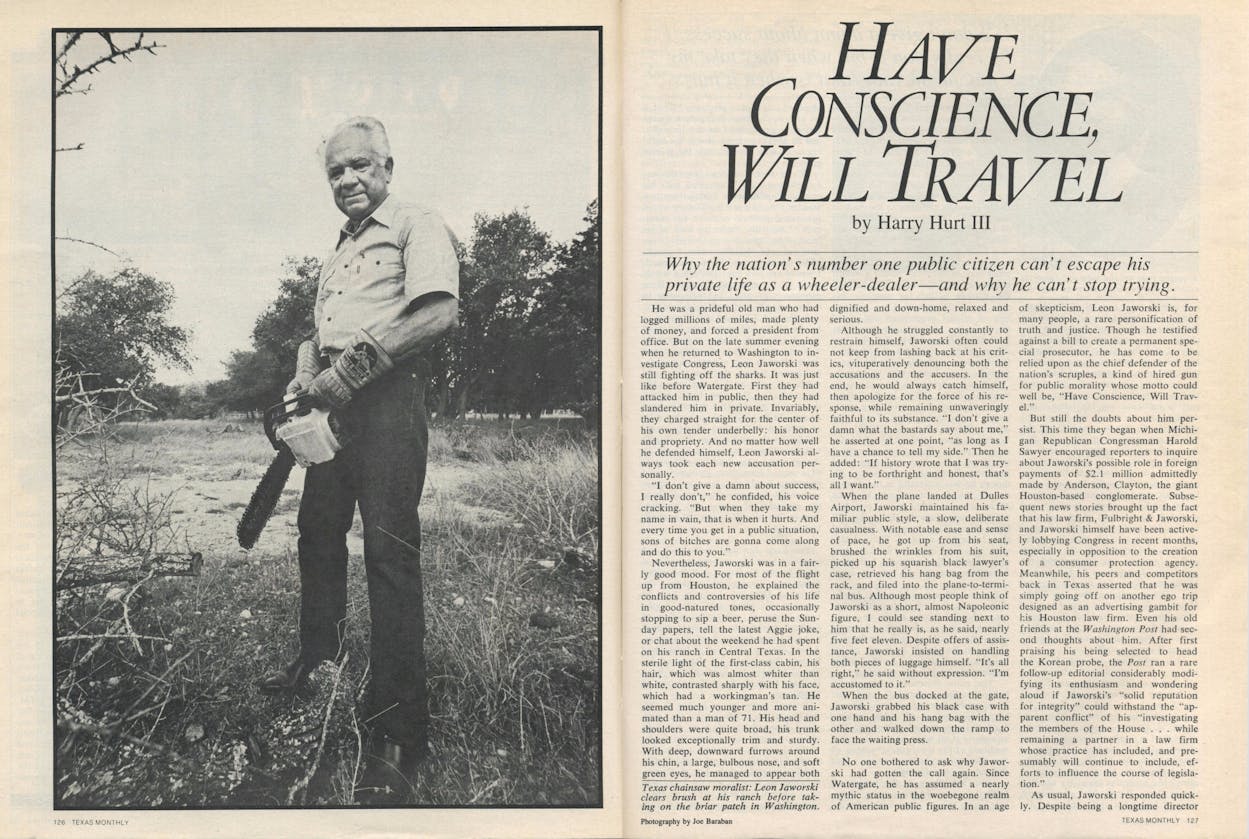

By this time, of course, Jaworski was approaching seventy, but he still ran to beat the clock. With the help of his law firm’s organizational apparatus, Jaworski had learned to structure his time so closely that he could continue to participate in public service roles like the Texas Constitutional Revision Commission, then return to his life in private business without missing a beat. “It was really very strange. Every day, Jaworski would seem to materialize out of nowhere just before nine o’clock,” recalls a fellow Constitutional Revision Commission member. “One minute, he would be nowhere in sight. The next minute, he would somehow appear in his chair. At five o’clock, he would disappear again just as suddenly as he had appeared.” Even when he spends weekends on his ranch, Jaworski stays on the move, cutting wood with his chainsaw, riding horses, pitching tennis balls to his grandchildren.

Amid his rush of accomplishments, Jaworski experienced his share of difficulties as a parent. His daughter Joan was a constant horsey-set companion of Joan Robinson Hill of Blood and Money notoriety and suffered through a couple of bitter divorces. In addition, her son Mike was killed in an accident on the ranch. Grandfather Leon had been extremely fond of the boy, and the loss hurt him terribly. Still, Jaworski has four other grandchildren, a daughter who is happily married, and a son who is an attorney with the prestigious Houston law firm of Bracewell & Patterson.

Although he had stopped trial work in the early sixties and turned increasingly to appellate cases, he had an impressive number of courtroom victories under his belt. Exactly how many cases Jaworski has won over the years is hard to say, since neither he nor his law firm could provide a complete record. Jaworski was uncharacteristically hazy in attempting to recall the exact number of jury trials he won, a statistic that many trial lawyers keep in that portion of memory reserved for one’s name and address. However, after some prodding, Jaworski estimated that his jury trial victories number “between fifty and a hundred.” He calculated the number of cases he has handled to be in the neighborhood of 500, or a rather conservative average of ten per year. Regardless of how many more cases he managed to squeeze in, Jaworski knew that the bulk of his life was now behind him, and he could feel sure that he had lived up to his father’s admonishment not to fail to achieve.

In October 1973, Jaworski got the most important telephone call of his life. It was Alexander Haig with a message from Richard Nixon: “He wants you, Leon.”

Jaworski had been considered for the job of special prosecutor earlier in the Watergate drama, but had turned it down because he felt it wasn’t independent enough. This time, however, he accepted. “One of the things I don’t think I deserve credit for is ‘timing,’ ” Jaworski remarked afterwards. “Either you have it or you don’t.”

Leon Jaworski proceeded to accomplish what Archibald Cox had failed to do. He rallied a disheartened staff, avoided the enticements and subterfuges of Nixon and his attorneys, and showed the embattled president that his only reasonable alternative was resignation. On October 15, 1974, after only eleven months as special prosecutor, Jaworski returned to Texas.

Watergate changed Jaworski’s life almost as much as it changed Nixon’s. After years of merely outstanding public achievements, he now had universal recognition and a solid place in history. He was wanted for speeches and award presentations all over the country. Publishers clamored for the rights to his book. Back home, his law partners, who claimed publicly already to have been in the process of shortening the name, changed Fulbright, Crooker, Freeman, Bates & Jaworski to simply Fulbright & Jaworski. Editorial writers from the Washington Post to the Terre Haute Tribune and the Sacramento Bee praised the great job he had done.

Not surprisingly, all this fired Jaworski’s impulse to sermonize. Like his earlier book, After Fifteen Years, his Watergate memoir read more like a moralist tract in the form of a legal brief than a behind-the-scenes account of how he forced a president from office. His standard speeches—of which he made over 180 in the days after Watergate—were in the same vein.

His friends noticed a personal change. “Leon got a lot more serious after Watergate,” observes Ed Clark. “He wasn’t as loose or as ready to have a good time as he used to be. People were always watching him. He had to be very careful about what he said.”

Still, not everyone was impressed. When Jaworski decided to step down shortly after Nixon’s resignation, the New York Times criticized his failure to finish prosecuting the other Watergate cases as “bordering on desertion of duty.” Others criticized him for not seeking an indictment of Richard Nixon, for failing to challenge Ford’s pardon of Nixon, and for his decision to allow former Attorney General Richard Kleindienst to plead guilty to a misdemeanor charge for his perjury before the Senate (Kleindienst later received a one-month suspended sentence and a suspended fine of $100). Later, accounts by former members of the Watergate special prosecution force revealed that Jaworski’s staff had often been intensely suspicious of Jaworski himself and his many private meetings with presidential adviser Haig.

Extremely sensitive to any sort of criticism, Jaworski seemed to want to reply personally to each and every point. But what surprised many editors and writers was the bitter-edged tone of his responses. Typically, he would blow up, vent his counterarguments, then cool off and attempt to make friends again. Upon reading James Doyle’s Not Above the Law, for example, Jaworski fired off a round of letters to New York Times columnist Anthony Lewis, who had written the introduction, and Harvard law professor James Vorenberg, who had served on the special prosecution staff, and contested Doyle’s account of intense intrastaff conflicts and the staff’s distrust of Jaworski. He later declared in a rather sardonic tone that Doyle had merely exaggerated the conflicts because “he had to sell his book.” However, upon arriving in Washington to begin the Korean probe, the first person Jaworski had dinner with was Jim Doyle.

Beyond all the give and take, not even Jaworski could deny that he had based many of his major Watergate decisions not only on his interpretation of the law but also on his personal view of what would be good for the country. If Jaworski thought Richard Nixon could never get a fair trial, he also thought that the trial of an American president would tear the country apart and should be avoided for that reason as well. Perhaps the best and most concise summary of the difference between Jaworski’s vision of Watergate and that of his critics is expressed in the contrasting ways he and Doyle ended their accounts. Jaworski closed his book with the comment that Watergate showed “no one—absolutely no one—is above the law.” Doyle ended his book, Not Above the Law, by observing, “It seemed that the higher up the ladder of power and responsibility the prosecutors reached, the more prevalent became the reduced sentences… At the top of the ladder, of course, was a former president of the U.S. named Richard Milhous Nixon.”

Watergate also seemed to put Jaworski at odds with his establishment past. He did return to his old positions on the boards of Anderson, Clayton, the Anderson Foundation, and Southwest Bancshares, but he decided not to rejoin the board of directors of Coastal States. According to law firm sources familiar with the situation, Wyatt offered Jaworski $20,000 in cash if he would come back, but Jaworski still refused, claiming he would be too busy to devote proper attention to the company. Fulbright & Jaworski nevertheless continued as Coastal’s outside counsel.

Jaworski also did not return to the meetings in George Brown’s Suite 8F. Given the heavy Vinson & Elkins representations in the 8F crowd, one of the reasons had to be the sticky little Connally matter. Early in Watergate, Jaworski disqualified himself from participating in any aspect of the milk-fund investigation that ultimately led to John Connally’s bribery trial. Many people assume it was because of his friendship with Connally. However, the reason Jaworski gave at the time was that his law firm was representing a client suing Jacobsen’s client, AMPI (Associated Milk Producers, Inc.). After Connally’s indictment and subsequent acquittal, Connally supporters blamed Jaworski for not intervening to stop the proceedings. Then, members of Connally’s defense team and his relatives and friends started vicious rumors about a deal between Jacobsen and Jaworski.

Any mention of the backlash from the Connally trial sends Jaworski into a tailspin. “It makes me so goddam mad,” he stormed at one point, cursing the “sons of bitches” at Vinson & Elkins who had tried to defame him. Then, he remembered himself, stopped, and apologized for his language. “I have some good friends at Vinson, Elkins,” he said, “but what makes me so mad is that they’re accusing me of doing wrong when I was trying to be honorable. I tried to be kind to Connally. But what they’re saying is that I should have stopped it, which would have been the most dishonorable thing. The other thing is, they’re jealous as hell.”

Meanwhile, Jaworski was never too busy to answer calls for public service. When Lieutenant Governor Bill Hobby needed a legal counsel to assist him in presiding over the impeachment trial of Duval County Judge O. P. Carrillo, he went to Jaworski hoping only for a few recommendations. To Hobby’s surprise, Jaworski immediately reached for his desk calendar and asked, “When do you need me?” The somewhat startled Texas Legislature was then rewarded with several days of Leon Jaworski, fresh from toppling a president, helping to preside over the toppling of a state district judge.

Later, when Nixon made his self-serving pitch to the American people in his interviews with David Frost, Jaworski quickly blasted him in the press, asserting that despite his continued denials, Nixon “had full knowledge of the [Watergate] break-in and was an active conspirator in the obstruction of justice.”

Then, in late July, Jaworski got the call again. This time there were two voices on the other end of the line. House Speaker Tip O’Neill and House Majority Leader Jim Wright of Fort Worth. Former special prosecution force member Philip Lacovara had just resigned as counsel to the House Conduct Committee’s investigation after a fight with Chairman John Flynt. O’Neill and Wright said that the integrity of Congress and the House leadership was at stake. They said they wanted Jaworski to make a complete investigation and promised he would have full independence.

“I was promised that once before,” Jaworski replied, “and I had to fight to get it.” Jaworski added that he was reluctant to take the job because of other commitments, but said he would let them know the following afternoon.

The next morning O’Neill and Wright called again. This time they put their request on the basis of Jaworski’s duty to his country. Against the advice of family and friends, Jaworski accepted. “It was just easier to go on and do it,” he remarked afterward, “than to have people think I was a coward or that I wasn’t equal to it. If I looked at it and analyzed it, I’d tell you that I was going to get scalped before I got home. But I don’t worry about things. I take ’em as they come. I feel like it’s a whole lot better for me to have said yes, after I’d been given everything I’d asked for, than to have had the feeling that I didn’t have the fortitude to go on and do it. The other thing is to say, ‘Well, you’ve put everything on the line.’ Suppose it is true. Wouldn’t it be like a coward to sit back and say, ‘Well, I’ve got it made, and I’ve had all these blessings and all of these good fortunes and I’m riding high and everything else,’ and here comes this thing where they say they need me, and then I say, ‘No, I might tarnish my reputation a little bit.’ This cannot be the test.”

On August 14, Leon Jaworski left for Washington again. But even as the Watergate hero returned, some former members of the special prosecution force still had their doubts about his ability to do the job. “In Watergate, Jaworski was quite conscious of the consequences raising charges would have for the careers of the people involved,” said one. “I’m sure he’ll be very circumspect in recommending charges against members of Congress and will probably see many of the things they do as peccadilloes rather than as derelictions.”

The plan of attack Jaworski had in mind on the flight up from Houston seemed to lend credence to this point of view. “I’m only going after quid pro quo,” he informed me, “I’m interested in cases where someone paid someone some money and got a vote. A lot of this stuff that’s come out so far is just the sort of thing that goes on in Washington all the time.”

But after meeting the investigation staff on his first trip to Washington, Jaworski said that he could accept the staff’s broadly outlined manual of offenses and indicated that his investigation might turn out to be more wide-ranging than he had originally anticipated. “It may be that I will have to do something out of the ordinary at some point down the line,” he said when he arrived at Dulles Airport for the flight back to Houston. “I don’t know yet.”

I did not intercept many more specifics of the Korean probe during the time I spent with Jaworski. However, I did experience several more revealing aspects of the Leon Jaworski personal touch. He was always extremely considerate, taking care to call me personally when he changed travel plans or plane reservations, always making himself available for lengthy interviews. He was not aloof in the manner of John Connally, nor did he try to wheedle, cajole, and dominate in the style associated with LBJ. He was easy to sit down and drink beers with, a man who could (and did) in the heat of Watergate describe former presidential counsel J. Fred Buzhardt as “friendly as a French pervert,” a man who could in the heat of the Korean probe take time out to wager a six-pack of beer on a trivial matter and remember to pay off when he lost.

This personal touch also included a remarkable eye for detail, considering how busy he was at the time. For example, in the course of our interviews, Jaworski wrote me several personal notes explaining his position in various cases and giving me lists of friends to interview and topics to explore. In one note, he mentioned that two of his partners had called him to say that I planned to do a “hatchet job” on him in my story; he closed the same letter saying that he looked forward to our next interview. Afterwards, he wrote my father, whom he knew on a passing social basis, to tell him how “thoroughly objective and fair-minded” I had been.

At first, these notes and letters seemed merely a not-so-subtle attempt to influence my story about him. Then, I concluded that more than anything else they were another sign of Leon Jaworski’s own thoroughness and his rather needless insecurity. If a “great man” is defined as one with the ability to affect the country’s most important events, Leon Jaworski will take his place beside LBJ as one of Texas’ unequivocally “great men” simply on the basis of his Watergate accomplishments. He will be remembered as a man who overcame the apparent conflicts and contradictions between his public and business lives to achieve the necessary removal of a president of the United States.

For most men, this would be enough. But Leon Jaworski is still driven to be better than he can possibly be. In our final interview, Jaworski said that he often felt that his life had been a race with time itself, a test to see just how much one person could pack into a lifetime. It is at once a measure of his success and a sign of his failure, now that he is old, that he feels he must keep on running.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Longreads

- LBJ

- John Connally

- Waco

- Houston