WHEN HE WON THE 1999 TOUR DE FRANCE, Austin’s Lance Armstrong didn’t say he was going to Disneyland, nor did he thank his mother. After crossing the finish line, the 27-year-old Armstrong paid due respect to the cancer he had to conquer before getting to the starting line. “I never expected to be here,” he said, standing in the shadow of Paris’ Arc de Triomphe. “I hope it sends out a fantastic message of hope to all cancer patients and all cancer survivors around the world…life can go on, and you can return to become an even better person.”

Almost three years ago there was some doubt that Armstrong would even live to see the 1999 Tour, let alone win it. Doctors had given him a fifty-fifty chance of survival after discovering “third-stage,” or metastasized, cancer in one of his testicles that had spread to his abdomen, lungs, and brain. After surgeries to remove the testicle and the lesion on his brain, Armstrong underwent a punishing twelve-week protocol of chemotherapy. Things looked so grim that the cyclist—known among friends and competitors as supremely confident, even cocky—began selling off prized possessions, including his $125,000 Porsche 911, because, he said, “I thought I’d never make another dime the rest of my life.” When his French racing team dropped him and his $2 million contract in 1997, he reacted philosophically: “I understand their hesitations and concerns. I might be damaged goods. I’m very curious to find that out myself.”

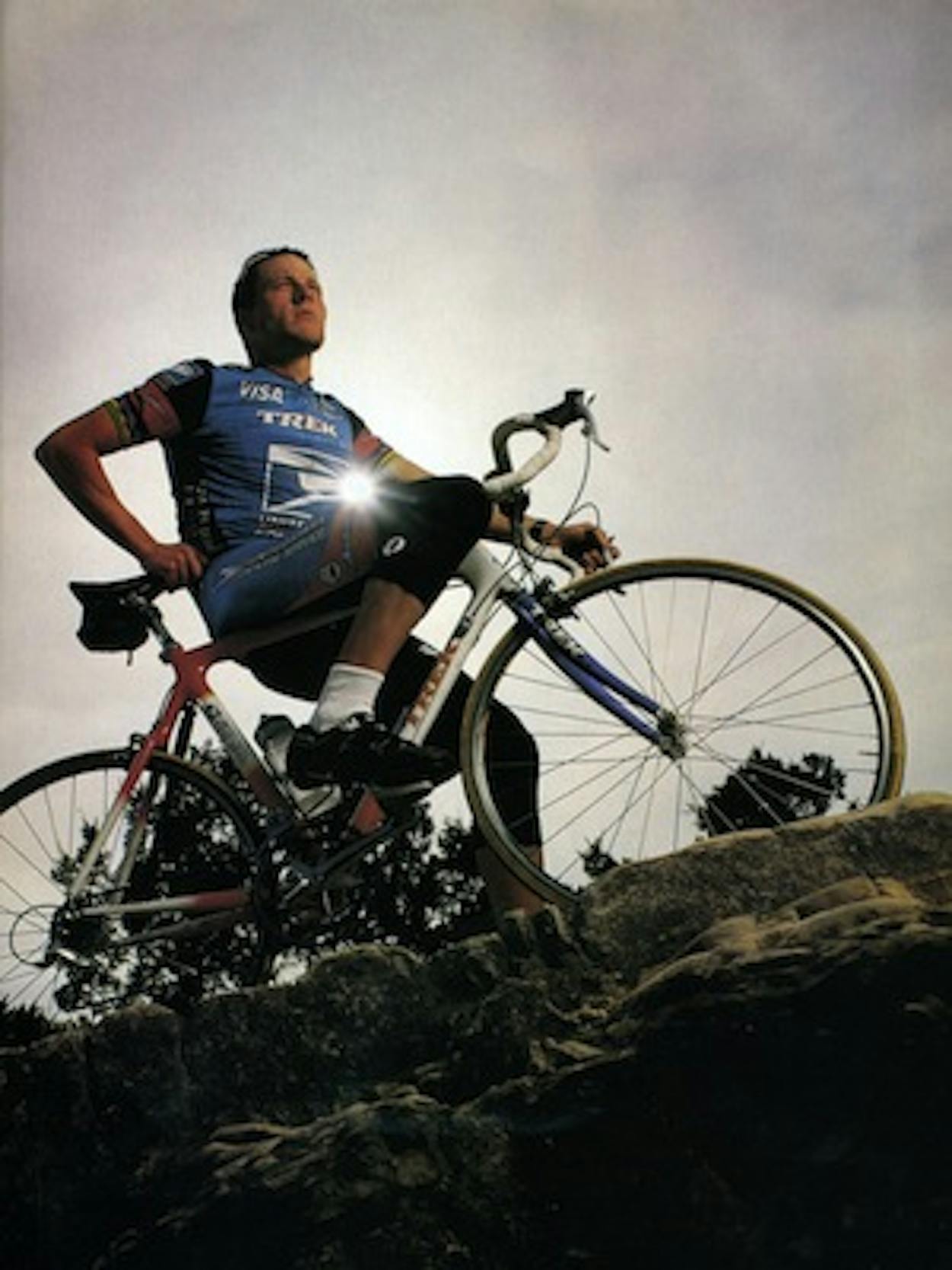

That question was answered loud and clear on Sunday, July 25, when Armstrong pedaled into Paris more than seven minutes ahead of the 140 other racers in cycling’s most prestigious and grueling competition. What isn’t so easily answered is, How did a young man who was sick enough to ponder his own mortality wind up outperforming his pre-cancer self? In other words, did Lance Armstrong win the Tour de France in spite of his cancer—or because of it?

His determination to return to normal “was evident from day one of his treatment,” says Dr. Dudley Youman, the Austin oncologist who first diagnosed Armstrong’s cancer and presided over his early treatment. Youman adds that Armstrong’s exceptional physical conditioning probably allowed him to withstand the rigors of chemotherapy better than the average person, and therefore to bounce back faster. “He continued to ride his bike at least some during the early chemo,” Youman says. “After his chemo, he told me he was feeling as strong as he ever had.”

If his battle with cancer prodded Armstrong to redouble his physical-conditioning efforts, it may also have changed his competitive psyche for the better. “Since the chemotherapy, he acts really different,” Adam Wilk, a childhood friend and fellow cyclist, told reporters after Armstrong’s big win. “He used to have that swagger. He…would ride with an attitude of ‘nobody can beat me.’ But now he goes out just to see how far he can push himself. I think that comes from beating cancer.”