She was such a familiar woman—a quiet, thoughtful, suburban mother with dark brown eyes and a generous smile on her good days. She was a devout Christian who read Bible stories to her five children. She constructed Indian costumes for them from grocery sacks. She gave them homemade valentines on Valentine’s Day with personalized coupons promising them free hugs and other treats. She was so protective of her brood that on trips to the grocery store, she had each of her four boys hold on to a corner of the grocery cart while her infant daughter sat in a car seat in the basket. On June 20 she decided she had had enough. Andrea Yates, 36 years old, called the police and asked them to come to the family’s one-story, Spanish-style house in Clear Lake, southeast of Houston. She led the officers past the plaque in the living room that read “Blessed Are the Children” and took them to a back bedroom where four of the Yates children lay shoulder to shoulder, their eyes wide open. In a calm voice she described how she had filled up her bathtub with water, then held the children, one by one, under the water until their little bodies had stopped squirming. The only one who had given her a problem, she noted, was seven-year-old Noah, who had tried to flee when he saw her drowning his baby sister, Mary. But she had caught him, brought him back to the tub, and then held him under the water until he could hold his breath no longer.

“Why?” the police detectives asked her. “Why?” She stared off into the distance. She was a bad mother, she said, and she felt that the children were disabled and not developing normally.

And so she decided to send them to God. She gave each of her children a baptism, then laid them out on the bed (except for Noah, who was left in the bathtub) like perfect little Christian saints.

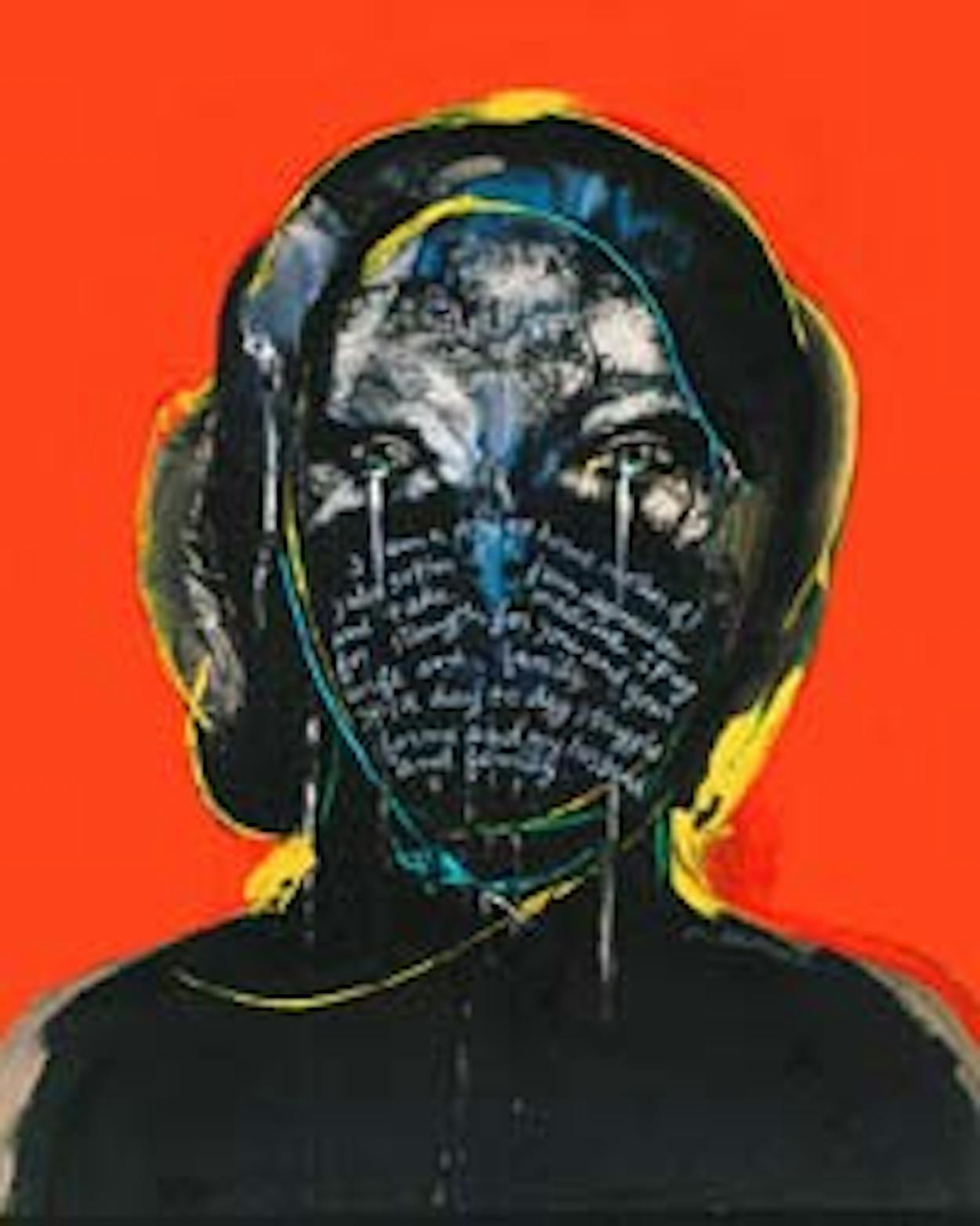

And that, in three short paragraphs, sums up one of the most sickening and yet mesmerizing murder stories in modern Texas history. Even now, more than a month since the drownings, people cannot stop talking about Andrea Yates. The attempt to answer the question of why she did it has become a small industry in this country. So far, her deed has been blamed on her post-partum depression after the birth of her fifth child, her fundamentalist religious beliefs, her doctors, her husband, who supposedly didn’t do enough for her, her extended family, who could have helped her more during her times of stress, and her suburban neighbors, who apparently were too consumed with their lives to notice what was going on in hers. What’s just as astonishing is the way Andrea Yates has triggered feelings of—and there’s no other way to say this—sympathy. The most striking event that took place in the immediate aftermath of the murders was not the impromptu press conference held by Andrea’s husband, Russell, the 36-year-old NASA computer scientist who appeared to be completely in shock as he held a photo of his family and spoke in a dazed voice about his family being normal. It was the mothers, some of whom brought their children, who came to the Yateses’ home to stand behind the police tape. Occasionally they darted underneath the tape to leave stuffed animals, bouquets, potted plants, poems, and letters beside a tree. One unsigned letter to Russell Yates began, “I am a stay at home mother of 3. I also suffer from depression and take medicine. I pray for strength for you and your wife and family. It’s a day to day struggle for me and my husband and family.” One woman told reporters that she too had suffered from post-partum depression after her son was born. “Thankfully I got help,” she said. “I never got to the point of killing him but … I know how it is. She basically lost herself.”

Just seven weeks before the drownings, there had been another horrific case of a parent murdering a child in Texas. A well-heeled Dallas accountant named John Battaglia was arrested for shooting his two young daughters to death while their mother, his ex-wife, listened over the telephone. He too had an emotional disorder. Yet he was quickly dismissed by almost everyone I talked to as another deranged, abusive man who should be sent off to death row as quickly as possible. Men who go mad do not interest us. But women who go mad are haunting—and when it came to Andrea Yates, the only person I could find in Houston who wanted her to go to death row was Dianne Clements, the president of a Houston victims-rights group called Justice for All, who said she was disturbed by the way Yates’s family and neighbors kept talking about what a lovely woman she was.

But there’s no denying that she was a lovely woman. Andrea Yates was not like Susan Smith, the young Union, South Carolina, mother who sent her car into a lake with her two sons locked inside because she had become involved in an adulterous affair with a man she thought would marry her only if her children were gone. Yates came with no baggage. She was the kind of young woman who went over to her parents’ house every day to take care of her father after he became afflicted with Alzheimer’s disease. One neighbor recalled seeing a pregnant Andrea on a ladder decorating a Christmas tree, then running around her parents’ kitchen, trying to feed her parents and children as her own plate grew cold. “She was always trying to be such a good girl,” her mother would later tell a reporter from Newsweek. “She was the most compassionate of my children. Always thinking of other people, never of herself.”

And that is perhaps what struck a chord in so many women. Here was someone like themselves, alone in a house with her children, often at wit’s end, yet continuing to deny her own needs to tend to her children and a husband who believed in a traditional family lifestyle. And the former high school football star Russell Yates, according to news-media accounts, was the definition of a straight-laced Christian traditionalist. He didn’t want his wife working outside the home; he didn’t want her to use baby-sitters because they might teach the children too many worldly attitudes; and he wanted the children homeschooled so that they would be kept away from the temptations of drugs, violence, sex, and un-Christian ideals that he believed were prevalent in public schools.

What’s more, Yates did exactly what so many other women do every day: She never let people around the community and neighborhood see what was happening inside her. Two weeks before the drownings, she went to a barbecue at her brother’s house, and according to one person who had been there, she was “rambunctious and happy.” Several days later, she showed up with her children at the Houston bookstore where she bought supplies to homeschool the older boys. Co-owner Terry Arnold, as usual, commented on how slim and attractive she looked. (“Andrea was not the stereotypical homeschool mom in long denim dresses,” says Arnold. “She wore T-shirts and blue jeans, and she could really look very attractive when she pulled her hair back in a long French braid.”) After noticing the children playing quietly in a corner of the store, the other co-owner, Joanne Juren, told Yates, “If we had a gold star to give to the best children, we would give it to yours.” Yates beamed and asked about enrolling her eldest, Noah, in a science class starting that fall. “This was not a crazy woman,” says Arnold.

Yet according to what Yates later told the police, she was already planning at that time to kill her children. She said she had been thinking about killing them for months.

You would have thought she would go down in history as the modern-day Medea. But within 48 hours of the murders, Yates had become a symbol of the precarious nature of American motherhood to a host of journalists, academics, and psychiatrists. The night after the killings, Nightline gathered a group of experts to talk about Yates and the potential dangers of post-partum depression in young mothers. Newsweek put together a cover story on Yates with a headline that read “Motherhood and Murder.” As part of the magazine’s package of stories, columnist Anna Quindlen wrote, “Every mother I’ve asked about the Yates case has the same reaction. She’s appalled; she’s aghast. And then she gets this look. And the look says that at some forbidden level she understands.”No one was quoted more in the aftermath of the drownings than Michelle Oberman, a professor at DePaul University College of Law and the co-author of Mothers Who Kill Their Children, which was recently released not by some cheesy paperback true-crime publisher but by the esteemed New York University Press. Citing research into a decade’s worth of child murders at the hands of mothers—there are some two hundred such murders a year in the United States—Oberman told me that a murderous mother “is often a reflection of the society in which the murder occurs. There are women with serious disorders who cannot parent their children the way social norms dictate, so they begin to feel more and more desperate.”

Meanwhile, a new generation of psychiatrists was leaping into the Yates media fray to state that the medical establishment was still not grasping the significance of the emotional anxieties in new mothers. They pointed out that some 80 percent of new mothers reportedly experience some form of depressed mood within the first two or three weeks of giving birth; between 5 and 20 percent experience more severe post-partum depression; and roughly one in one thousand experiences a devastating post- partum psychosis in which she loses contact with reality, starts hearing voices, and experiences hallucinations that could lead her to take her own life or the life of someone else.

One of those frequently interviewed psychiatrists was 41-year-old Lucy Puryear, who is on the faculty of the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. She said she was “amazed” at how many women she meets suffer from this kind of depression, which has never been properly diagnosed. When I asked Puryear how quickly post-partum depression, which is characterized by withdrawal, despondency, and fatigue, could lead to post-partum psychosis, she replied that such an event would be “extremely rare.” But if it did happen, she said, “it could happen in the space of a week or two.”

All this talk in the news media set off something of minor panic—at least in Houston. Within a week after the drownings, four women called Child Protective Services and asked that someone come get their children because they were suffering from post-partum depression and were not sure what they might do. It was an interesting response considering that no one was sure what level of post-partum depression Yates had endured and what the long-term mental repercussions had been. (The only information about her post-partum problems has come from her brothers and her husband; the doctors who have treated her remain tight-lipped.)

In fact, no one had any real idea when Yates’s mental illness began—one longtime friend said she had displayed minor depression back in high school—and no one was sure what caused it to escalate. One of her brothers said he noticed “changes” in Yates’s demeanor even before she began having children in 1994. The slide continued with a miscarriage between the births of her third and fourth children. Little by little, she withdrew. Her first suicide attempt—she took an overdose of her father’s Alzheimer’s medication—came in June 1999, four months after the birth of her fourth child. Back then, a neighbor would later say, she seemed to be struggling, trying to care for her father and her children at the same time. But if that was the source of her stress, Yates never talked about it. She had become so private, one of her brothers later said, that she wouldn’t tell anyone what led to her attempted suicide.

After hospitalizations and intensive drug treatments, there were times when her condition seemed to improve. Her husband said that at one point she completely “snapped out of it” after a regimen of anti-depressants and Haldol, a powerful drug used to treat delusions, schizophrenia, and mania. But after her father’s death this past spring, in a bedroom at her mother’s house, she held a knife against her throat and threatened to kill herself. She was hospitalized again. When she was released, Russell’s mother came each day to help her care for the children. One day she saw Andrea in one of the rooms, straightening it to make room for the baby’s crib. She decided that Andrea must be feeling better. But the next morning, one hour before her mother-in-law was scheduled to arrive, Andrea and the children kissed her husband good-bye as he left for work, then she took the children inside to drown them.

Today, what’s left is a lot of finger-pointing, and much of it is directed at Russell Yates. “Am I the only person wondering exactly what Russell Yates was thinking every morning when he left his house and went off to work … leaving his five children at home alone with a mother who was so depressed that in 1999 she tried to kill herself?” snapped Jan Jarboe Russell in her San Antonio Express-News column. Andrea’s brothers and sister have told the press that Russell did not give his wife a break from the stress—they say she never had time away from the kids—and that there was no reason for him to try for a fifth child after the depression Andrea had experienced from the birth of their fourth.

Did Russell spend more time trying to hide his wife’s illness than trying to fix it? His friends insist he was doing everything he could to help Andrea get well, taking her to a variety of hospitals and doctors, keeping track of her prescriptions on a board at home, and even inventing little games with his children that they hoped would coax her out of her dark mood. “He didn’t see what was coming,” says his friend Rick Mayfield. “Do you really think that if he thought his wife was going to kill his children, he would have gone to work?”

It could well be that none of this would have happened if Andrea had remained on the anti-psychotic drug Haldol. According to Russell, she was taken off the medication two weeks before the children’s deaths. But who knows if that would have saved her? Who knows what might have happened if she had spent more time away from the kids, if she had not led such an isolated life (the Yateses didn’t even attend church), or if more of her neighbors had taken the time to talk to her?

Andrea herself certainly isn’t offering any insight. When her brother and sister visited her recently in jail, she stared blankly at a wall, her long hair askew and her arms tightly folded. She didn’t seem to know what had happened to her children, but at one point she did ask if a funeral had occurred. They told her it had. It had been a beautiful funeral, in fact. Russell himself had delivered the eulogy, speaking for nearly an hour about his kids. At the end, he approached each of the children’s small white caskets and tucked their baby blankets over their bodies. Then, just before he left each child, he bid them farewell. To Noah he said, “You’re in a better place.”

It was an odd comment to make—for that was exactly what had driven his wife to murder the children. She too had wanted them to be in a better place.

- More About:

- Crime