Appropriately enough for a guy who talks to himself for a living, Jeff Dunham is a little complicated. On the one hand, the Dallas-born ventriloquist is the most popular comedian in America. His DVDs have sold six million copies. His YouTube clips have been viewed half a billion times. Forbes recently declared him the highest-paid comic in the country, with an estimated annual income of $22.5 million. On the other hand, for every fan who loves Dunham, there’s someone else who really does not. Critics have branded him a racist, a sexist, and a homophobe. His most popular character, a bug-eyed skeleton named Achmed the Dead Terrorist, has been denounced as an example of “outstanding Islamophobia.”

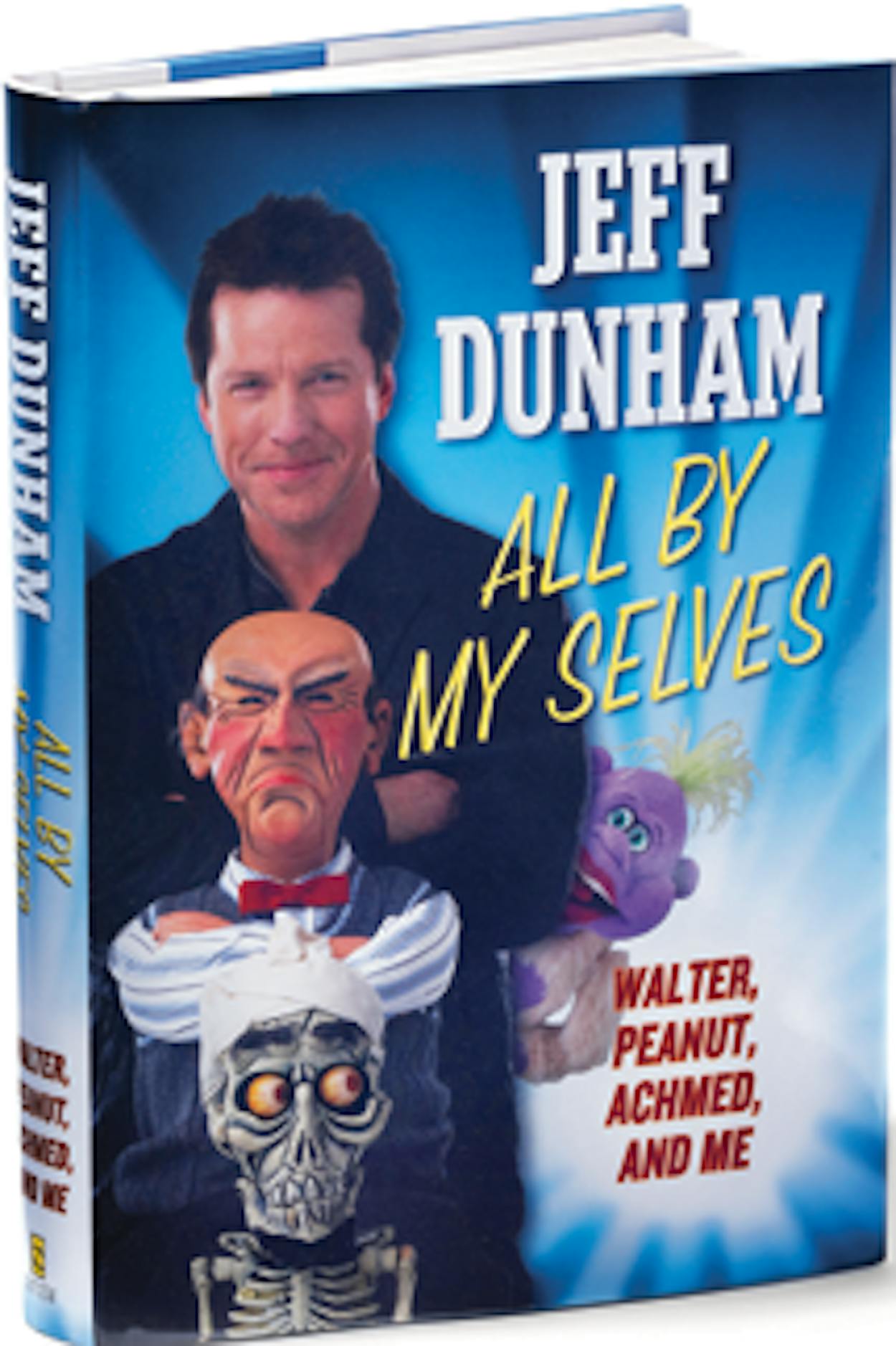

One person whose take on Jeff Dunham has rarely been heard is Jeff Dunham. In interviews, he has long been reluctant to scrutinize his own work. So one approaches his memoir, All By My Selves: Walter, Peanut, Achmed, and Me (Dutton, $25.95), with curiosity, if mild skepticism. The book obligingly traces Dunham’s rise with earnest anecdotes about his childhood, career, and family. But given the opportunity to grapple with his critics, Dunham does so only glancingly. By turns reflective and self-serving, he comes off as a basically decent guy with a deeply cynical act.

Texas comedians tend to fall into one of two groups: button-pushing provocateurs (Bill Hicks, Jamie Foxx) and plain-talking good ol’ boys (Blue Collar Comedy Tour vets Bill Engvall and Ron White). Dunham is a bit of both. Everything about him is slightly old-fashioned, from his retro-vaudeville routine to his Boy Scout charm. A Baylor alum, he grew up in Richardson, the son of a real estate appraiser and a housewife, with all the trappings of a seventies Texas boyhood: rooting for Staubach and the Cowboys, working a summer job at Six Flags, going to Luby’s every Sunday after church. In keeping with his straight-laced upbringing, Dunham plays it safe in the part of his act where he performs without dummies, telling jokes about airport security and his dog. The dummies, meanwhile, seem similarly nonthreatening. There’s Peanut, a fuzzy purple ape thing; Walter, a wizened old grump; and José Jalapeño on a Stick, a, um, jalapeño on a stick. They’re a cute, harmless-looking bunch—until they open their mouths.

Humor, it’s often said, is based on incongruity—the gap between what’s expected and what really occurs (think of the semantic left turn of “Take my wife . . . please”). In Dunham’s comedy, this disconnect comes from cartoonish puppets saying obnoxious things: Black people are drug fiends, Mexicans are lazy, Jews are cheap, gays speak with a lisp. In All By My Selves, Dunham claims to make comedy for “Middle America, all the normal folks out there.” Just don’t think too much about his definition of “normal.”

A charitable observer might chalk these stereotypes up to simple ignorance. In one of the book’s more embarrassing passages, Dunham recounts the creation of a particularly fraught dummy, a jive-talking black pimp named Sweet Daddy Dee. First, he writes, he “got on the Internet and found some black guys whose faces I really liked”—a sentence that encapsulates a particularly twenty-first-century form of cluelessness (couldn’t he at least have gone to the mall?). Later, when it comes time to flesh out Sweet Daddy as a character, Dunham starts by enlisting the help of some actual black people but ultimately decides he’s better off watching Snoop Dogg DVDs and browsing “urban” dictionaries online. Racist? Not exactly. Oblivious? Fo’ shizzle.

Other times, Dunham seems to know better. Onstage he plays the role of straight man, delivering not-quite-convincing rebukes to his dummies’ outbursts. Take this typical exchange, between Dunham and Walter:

Walter: I dated a girl in India. Lovely young lady. Weird-ass country.

Dunham: What was wrong with India?

Walter: Most of the women got a red dot in the middle of their forehead. What the hell is that? “YOU. ARE. HERE.”

Dunham: [nervous look]

Walter: Maybe it lights up when the coffee’s ready.

Dunham: [to audience, embarrassed] I’m sorry.

Walter: Scratch it off, you frickin’ win something.

Dunham: Will you stop it!

Clearly Dunham knows these jokes have the potential to hurt. And yet in his book he refuses to acknowledge it. He writes that “literally only two or three times in twenty years did someone get upset and think I was being racist”—a suspiciously small number, considering the space he devotes to justifying himself. In the section about Sweet Daddy, he writes, “As far as the people with whom I spoke after the shows, I didn’t seem to be offending anyone”—apparently not considering the possibility that someone who finds Dunham offensive probably wouldn’t pay $70 to see him in the first place.

Dunham’s detractors sometimes portray him as a red-state rube, Larry the Cable Guy with hand puppets. But Dunham is smarter than that. All By My Selves reveals him to be a savvy operator: a pioneer in direct marketing, an early adopter of the viral power of the web, an unabashed merchandiser. He describes tailoring his Achmed jokes so as not to offend “the majority of people” (the implication being that offending a minority of them is okay). The man knows what he’s doing.

If only he would admit it. Take, for example, Achmed, who utters curses like “Allah-dammit” and spells his name “A . . . C . . . phlegm . . .” Dunham has repeatedly insisted that the character is “absolutely not Muslim.” Honestly, though: a man named Achmed, with a beard and a turban, who eagerly awaits the 72 virgins he’ll meet in heaven? Let’s just say he won’t be attending a house of worship near ground zero anytime soon.

This kind of disingenuousness is the most frustrating thing about All By My Selves. Many comedians use stereotypes to entertain and provoke. But instead of owning up to it, Dunham hides behind the cover of his dummies. “It’s the little guys, not ME!” he writes. “I’m as stunned and as offended as the audience.” Never mind that the audience supposedly wasn’t offended in the first place.

The thing is, Dunham doesn’t seem like a bad guy or even particularly bigoted. The jokes his puppets tell are more tired clichés than incendiary hate speech; even his straight-man reactions aren’t so much appalled as embarrassed, which seems about right. For all his critics’ anger, Dunham’s act isn’t suffused with racism. It’s more like nostalgia, for a magical time when Americans spoke English, the phrase “Christian morals” was redundant, and gay jokes were as acceptable as smoking while pregnant—a world that looks a lot like, say, Richardson, circa the seventies. And as a devoted square, savvy entertainer, and above all else, astute businessman, Dunham will keep trying to preserve that world, for as long as the audiences keep laughing along.

TEXTRA CREDIT: What else we’re reading this month

Lone Star Noir, Edited by Bobby Byrd and Johnny Byrd (Akashic, $15.95). Fourteen bleak stories from the likes of James Crumley and Joe R. Lansdale. Buy it at amazon.com.

Every Riven Thing, Christian Wiman (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $24). Poetry as spare as the West Texas landscape the author was raised in. Buy it at amazon.com.

As a Farm Woman Thinks, Nellie Witt Spikes (Texas Tech University Press, $34.95). The selected newspaper columns of a High Plains pioneer. Buy it at amazon.com.