It was supposed to be just another game.

The Eastwood High School–Plano Senior High matchup had been scheduled for more than a year, a routine early-season nondistrict contest. Then, on August 3, a month before the game, a 21-year-old man drove hundreds of miles from North Texas to El Paso. He went to a Walmart on the east side of town, a few miles from Eastwood High, and in a matter of minutes killed 22 people and injured 25 more. After turning himself in to police, he reportedly said he’d come to El Paso to “kill as many Mexicans as possible.” The shooter, it turned out, was a graduate of Plano Senior High.

Suddenly, a matchup between distant high schools had become a contest between two communities linked by an act of horrific violence. Twelve days after the shooting, Plano Independent School District officials canceled the game, scheduled to be played in nearby Murphy, citing “safety concerns for the participants and fans of both teams.” But the officials didn’t spell out what those concerns might be, and the Plano police department said there were no credible threats.

The outcry against the school district’s decision was immediate and intense. El Paso school board members publicly criticized their counterparts in Plano. The mayor of El Paso said Plano’s decision was “not very well thought out.” Presidential candidate Beto O’Rourke suggested moving the game to El Paso, tweeting that his hometown was a “strong, safe, beautiful, binational community.”

El Pasoans weren’t the only ones outraged. Lily Ray, a senior at Plano Senior High, started an online petition asking that the matchup be reinstated. Dale Hansen, the longtime sports anchor at WFAA, the ABC affiliate in Dallas, blasted the decision in a withering commentary. “When we cancel games because we’re afraid to live,” Hansen said, “the bad guys win.”

The uproar went national, attracting the attention of the Associated Press and the Los Angeles Times. Julio Lopez, the thirty-year-old head coach at Eastwood, suggested to reporters that if Plano didn’t want to host his team, they could meet in Midland or Odessa. “We’ll play anywhere,” he said.

The backlash had its intended effect. Roughly 24 hours after the game was called off, Plano ISD reversed its decision. The match was rescheduled for September 5 and moved to Frisco’s Ford Center, where the Dallas Cowboys practice. And WFAA announced that the game would be broadcast on network television all across the state. Hansen would call it live.

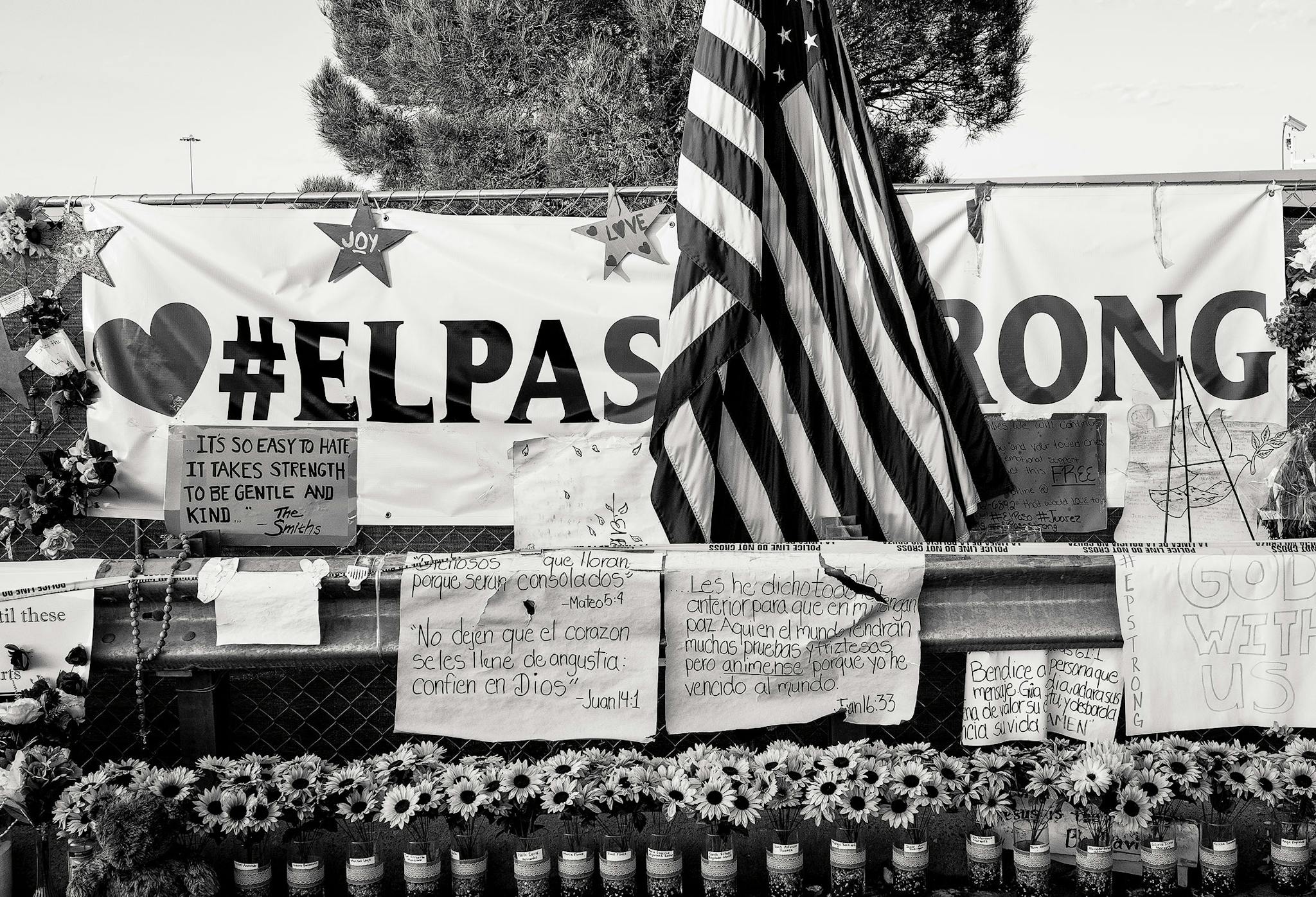

The buzz surrounding the game only escalated from there. Lopez, who had played wide receiver at the University of Texas at El Paso, received a dizzying number of interview requests from media outlets. He didn’t turn any of them away. El Paso is often an overlooked part of Texas—it’s as close to Denver as it is to Dallas—and he knew that it was getting attention now only because of the tragedy. Lopez saw an opportunity to tell a different story about his city. A story of perseverance. Something that would exemplify the rallying cry that adorned stickers and T-shirts and homemade signs: “El Paso Strong.”

What became clear throughout the week leading up to the game is something that communities all across Texas have long understood: football is about far more than what happens for four quarters on Friday nights.

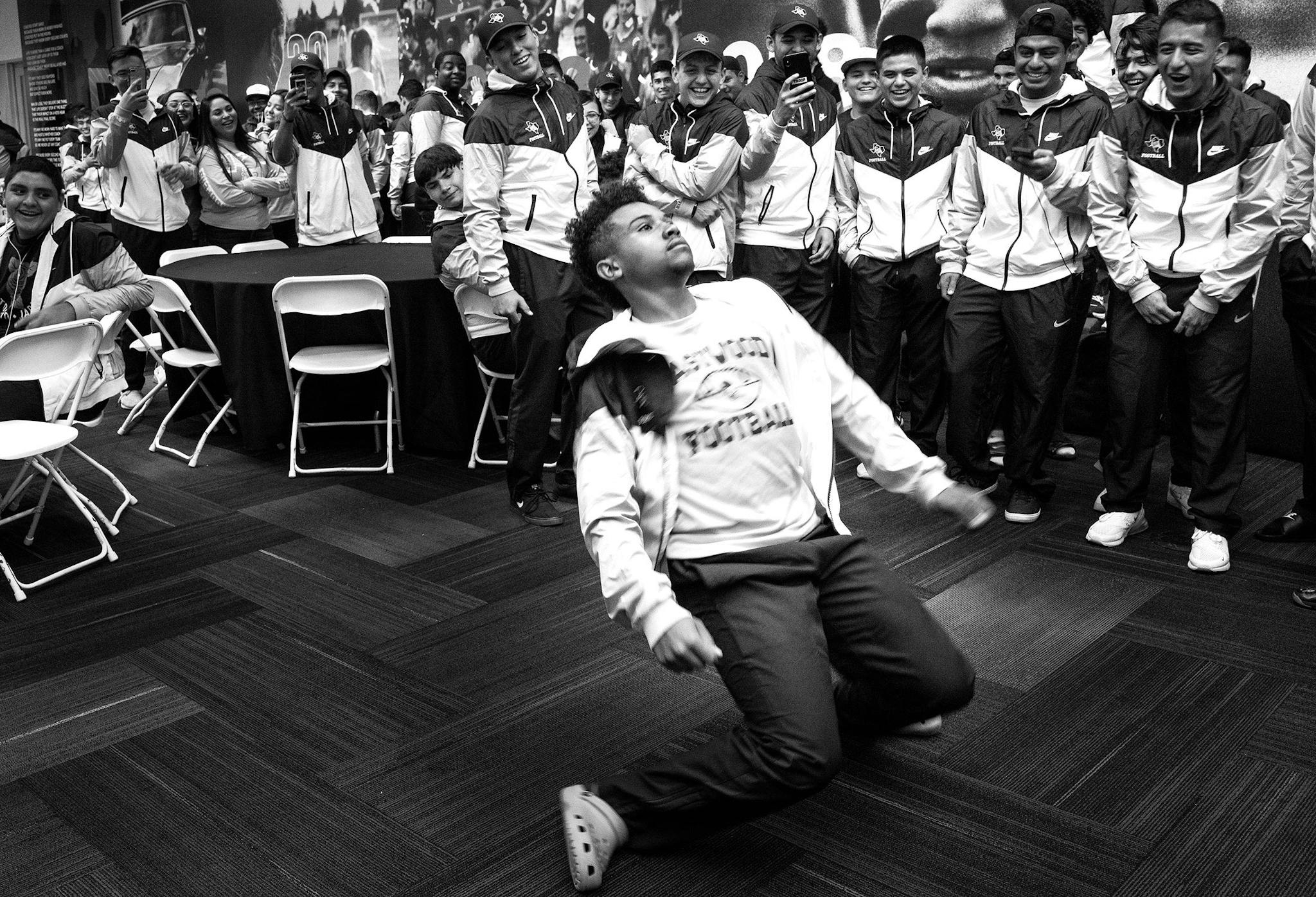

When Eastwood arrived in North Texas, local restaurants offered the team free meals. When they pulled up to the Cowboys practice facility, owner Jerry Jones was there to greet them. (“That’s the hand that signs the checks,” one of the players said after shaking Jones’s hand.) In a display of unity, Plano Senior High invited Lopez and David Boatright, Eastwood’s principal, to attend their school’s pep rally. (“You know,” Lopez said while walking into the school, “I’ve never been to the pep rally of the team we’re playing.”) There, Lopez gave a speech in which he described the love he’d felt from the Plano community as “awesome.” He thanked the students and school leaders for their hospitality, and he personally thanked Ray, the student who had started the online petition. The audience roared.

The day of the game, both Eastwood and Plano Senior players received a message of encouragement from an unexpected source: the Houston Texans. “We stand alongside you,” the team tweeted. “We’re rooting for you. We’re proud you’ve found strength in bringing your community together through football.”

Lopez had a similar message prepared when he gathered his players in the locker room for a pregame pep talk. “We know we’re playing for a town that’s hurting,” he said. “We know we’re playing for a city that’s counting on you.”

As he spoke, he paced the locker room, staring each player in the eye, his voice gradually growing louder, faster. “You’re gonna go through adversity at some point. We might be down. We might have a turnover. We might have something happen that we have to come back from. But we’ve been dealing with that for a month! It’s about how you handle that adversity.”

He reminded them of all the people who would be watching on TV, the kind of audience they had dreamed of playing in front of when they were young boys. “I want to see that kid with a smile on his face tonight. Because you deserve it. This program deserves it. This city deserves it. And we deserve to go out on top!”

The team stormed out of the locker room and onto the field.

Just before kickoff, all of the players lined up for the National Anthem, shoulder to shoulder across the field, Eastwood players interspersed with Plano’s. Midway through “The Star-Spangled Banner,” everything began to overwhelm senior Eastwood defensive back Nathan Carranza: the grief his city was experiencing. The sheer exhaustion of it all. He thought of Eddie Cruz, a recently graduated Eastwood player who had remained close to the current team. In yet another tragedy, Cruz had drowned just a few days earlier.

Carranza peered down at the turf. Tears smudged the black paint on his cheeks. The Plano player standing next to him, a lineman named Dominick Herrera, recognized what was happening. He reached over.

“He held my hand,” Carranza said later. “He was just trying to be there, and I appreciated him for that.”

The game itself started out evenly—the two teams traded touchdown drives—but a couple of crucial errors caused Eastwood to fall behind. By halftime, they were down 23–7.

Lopez rallied his team, and in the second half, El Paso mounted a dramatic comeback. Star quarterback Christian Castaneda burst through the defensive line, stiff-arming would-be tacklers, connecting on nearly every pass he attempted. Four minutes into the third quarter, El Paso was celebrating in the end zone.

Lopez called for an onside kick. Plano recovered. But for the first time all game, the El Paso defense forced a punt. Eastwood marched down the field again, the drive stalling just inside Plano territory. On fourth down, Lopez decided to go for it. Castaneda dropped back and heaved a pass more than 40 yards for a touchdown, cutting the deficit to 23–20.

All of the momentum had shifted to Eastwood. Then a potentially game-changing play turned disastrous.

Early in the fourth quarter, Eastwood defensive lineman Pablo Duran drilled the Plano quarterback behind the line of scrimmage. The ball squirted loose, and after a quick scramble, Eastwood recovered. But the referee inexplicably ruled it an incomplete pass. A replay on the scoreboard confirmed what Eastwood fans already knew: it was a terrible call, a clear fumble.

Three plays later, Plano scored a touchdown. They quickly scored twice more, making it 43–20.

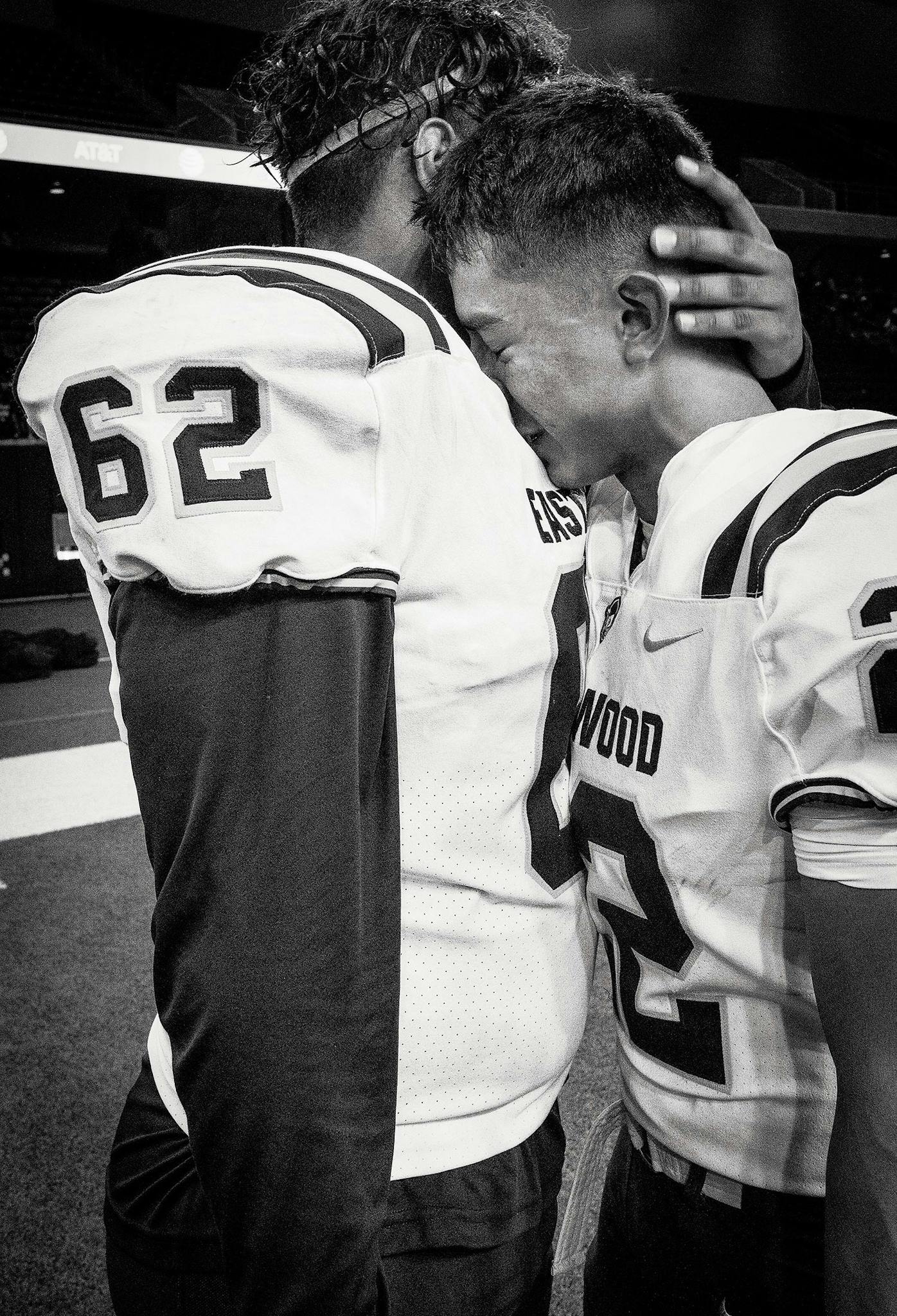

Eastwood never gave up—Castaneda punched in another touchdown—but there was no Hollywood ending on this night.

Afterward, the team boarded the bus to go to Main Event, which had offered each of the players unlimited bowling, arcade games, and laser tag. When they arrived, Lopez stood up and turned to address the team. Inside was a buffet of sliders and miniature hot dogs and hush puppies. In the morning, they’d get up and set off on the eleven-

hour drive back home. On Monday, most of the players would attend the funeral of Eddie Cruz. Then they’d go on with the rest of their season.

“Normally, after a loss, I’d say you should all try to be quiet, try to think about how to fix our mistakes,” the coach said. “But not tonight.”

He looked up and smiled.

“Tonight, I want you to go be kids.”

- More About:

- Sports

- Photo Essay

- High School Football

- El Paso