The kids fell in love with him first. Back in the late eighties, Craig Lewis lived three houses down from Linda Sanders. He was a quiet, solitary beanpole of a man with a copper-colored golden retriever named Shogun. He looked to be in his late thirties, and Linda knew from neighborhood gossip that he had one marriage behind him, just like she did. Back then, Shogun seemed to be his constant companion. Craig had taught that dog to do just about anything; of course he could sit, stay, and fetch, but he also knew how to play hide-and-seek with even the canniest kid. That was why, as soon as Linda’s children saw Craig’s pickup pull into his driveway in the early evenings, they were out the door. Leslie was six and Eddie four, two blond-haired kids on the run, raising small clouds of dust as their feet slapped the parched summer grass. “Don’t wear out your welcome!” Linda warned to the sliding door they slammed behind them.

It was always this way. The sky would turn dusky and the shadows would grow long before she’d give up waiting for their return, wipe her hands on a dish towel, and head off after them. On one such evening, the last light of the day was at her back, heating her neck and shoulders, and the hot, damp closeness of a Houston summer took her in its seasonal embrace. There were people who swore it always cooled off at night here, but Linda knew better.

It was natural that her kids would go looking for a man to replace the one who’d left them. Craig was handy, that was for sure: when Eddie dragged his broken bike to his door, Craig fixed the chain. Once, when Linda’s air conditioner went out, Craig came over and repaired it for her. If the kids were talking about the moon or stars, he would haul his telescope out and let them peer through it at the night sky.

A slight woman, Linda had a smile that was both knowing and tentative. Her thin blond hair fell lank below her shoulders. Like her street—small frame houses guarded by graying privacy fences—she could have been pretty if she fixed herself up, but who had the money or the time? She was recently divorced and was barely making ends meet as a department manager at a Randalls grocery store. Every day seemed like the one before it: get up, get the kids out the door to school, get them home, help them with homework, feed them dinner, give them baths, put them to bed, and, in the morning, get up and do it all over again. She was in her late twenties, going on forty-five.

Maybe that’s why she found Craig’s place such a comfort. Her front yard could have been mistaken for a small day-care center, with the kids’ toys scattered all over the place; his was manicured and trimmed, like a married couple’s. Craig was then an electrician for the city; he had walked away from community college just shy of graduation because he had already begun working full-time as an electrician and didn’t see the point. The engineers he worked with—the ones with the big degrees—started asking him for advice after his first few months on the job anyway.

Wanting to get out of the sun, Linda pushed his front door open, something Craig had told her she was welcome to do. She entered the living room and found Craig folding laundry while Leslie sat nearby, doodling in one of his notebooks. Eddie, meanwhile, was playing with Shogun. It was like they were a family already.

She shooed her kids toward the front door, patting them with her palm between their shoulder blades to hurry them along. She thought to herself that nothing makes a man more handsome than acting in a fatherly way with kids.

That was how Craig and Linda started spending time together. She’d rent a video and then pass it on to him, since it was good for two days. If she made extra for dinner, she’d take him a plate. Once, the kids locked her out of the house and she had to go to him for help to get back in. Craig came over, took the sliding door out, then put it back in and gave her a stick to put at the base to keep burglars away. He was around so much, in fact, that Linda’s mom, who’d bring ice cream sandwiches to the kids when she visited, started to bring some for him too.

Craig was very sick, the doctor said. He had only a fifty-fifty chance of making it through the night.

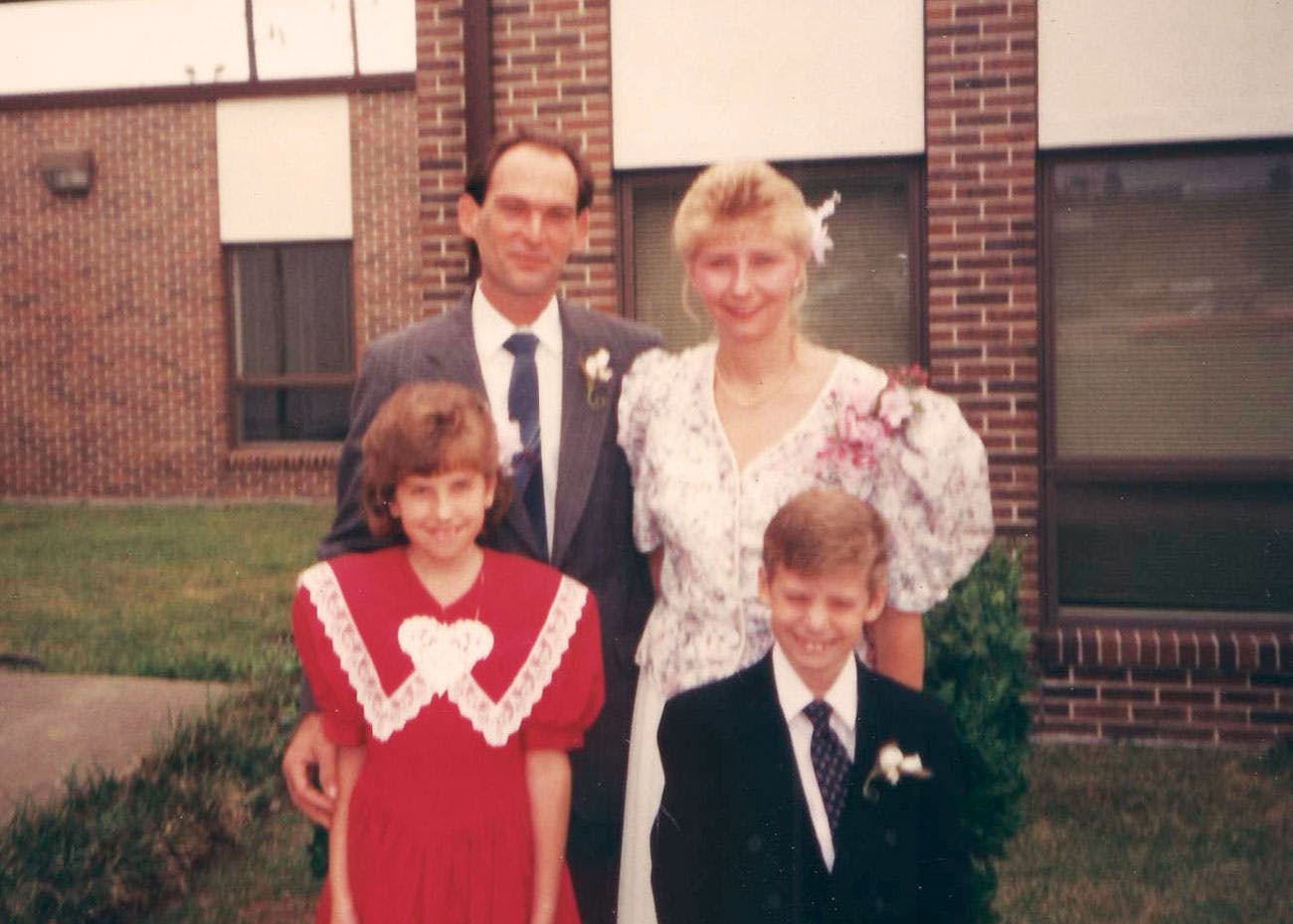

They got married at the courthouse on October 15, 1993. She was 30, he was 37. “Should we bring the kids?” she’d asked the day before. “Of course,” he said. “I’m marrying them too.” Just after the wedding, a friend of Craig’s from high school told Linda that Craig had been in love with her from the first time they’d met—he’d just been too shy to speak up. Their wedding gift to each other was a hand-cranked ice cream maker.

She felt as though she had married a man who could do anything. When he spied her recipe cards scattered in a kitchen drawer, he made Linda a recipe box out of polished oak. He was so patient helping Leslie with her homework that she fell in love with math. He built model boats and cars with Eddie. First the garage and then the house began to fill up with Craig’s projects. When he became interested in chemical reactions, he built himself a centrifuge. He’d been a welder back in the day; now he bought himself an anvil and forge. Linda thought he was the smartest man she’d ever met. She had been crazy in love with Craig when they married, but sometimes it caught her by surprise how much her love for him deepened over time.

That was how it was for almost seventeen years, until the day Linda felt a dark cloud pass ever so lightly over their otherwise sunny lives. “I think there might be something wrong with my heart,” Craig told her one evening after work. He said it the way he said everything—calmly, quietly, as if assuring her she shouldn’t worry.

It was the summer of 2010; Craig was 54 and had hardly taken a sick day in his life. His dad had lived to 91, and his mother was still fit at 89. He could outrace the kids on bike rides, no matter how fast they pedaled. But now he couldn’t sleep. Something about his heart felt off, like it had an extra beat. Craig made an appointment with a cardiologist, who didn’t find anything wrong. No reason to worry.

So Craig went back to doing what he’d always done. But instead of staying up reading late into the night, he’d fall into bed early, exhausted.

“I’m tired,” he told her.

“Well,” she said, “you should be tired. I’m forty-seven, and I’m tired.” But really, she wasn’t tired, and she didn’t think he should be either. Something was wrong with the love of her life, and Linda Lewis knew it.

By October the heat was beginning to recede, giving way to that sweet, gentle coolness that can make even the most jaded Houstonian feel grateful. But Craig continued to have trouble sleeping; he seemed to be drained even before he started work each morning.

On Thanksgiving Day 2010, Linda got up before dawn to the sound of Craig’s coughing and wheezing. He had caught a cold and hadn’t been able to sleep at all for the past few days. Linda took one look at her husband’s ashen face and threw on a T-shirt and jeans. “We’re going to the emergency room,” she said.

The highway was nearly empty, owing to the holiday, and Linda flew past the billboards, pine trees, and downtown towers without a glance, craning her neck for a first glimpse of the Texas Medical Center. “You all right, baby?” she asked, but Craig wasn’t up to talking. The fifteen-minute trip to St. Luke’s hospital was a blur.

In the emergency room, a doctor put a stethoscope to Craig’s chest and didn’t seem too worried by what he heard. Probably pneumonia. Craig left with a round of antibiotics.

Over the next few days he rallied. The color came back into his cheeks, and he got out of bed to attend to some of his projects. But then the antibiotics stopped working, and his symptoms came back worse than before. He went to see their family doctor for advice. “I think something more is going on,” the doctor said carefully. He prescribed another round of antibiotics, stronger ones this time.

On New Year’s, Linda noticed that Craig’s ankles were swollen to twice their normal size, bloated and discolored, as if they might burst. The swelling continued to get worse, and within days Craig wasn’t able to walk. This time he traveled to St. Luke’s by ambulance, and the next day he went into respiratory failure.

Linda sat in the small waiting room for hours before growing impatient and going to check on him. In the hallway she ran into his doctor, and Linda could tell by the stony look on his face and the speed of his stride that he was angry. He had overheard Linda telling someone else in the ER that Craig didn’t have heart trouble, and he started shouting at her. “How can you say your husband doesn’t have heart problems?” he demanded.

“He doesn’t,” she said, recalling what the cardiologist had told Craig. But her voice wasn’t as firm as she would have liked it to be. She was confused.

Craig had septic shock and pneumonia, the doctor told her. And, worse, his heart was barely beating. How could she not have known? Why had she waited so long to get him to the hospital? Seeing the bewilderment on her face, the doctor took a long, slow breath and softened his voice.

Linda listened, trying as hard as she could to pay attention even though her mind was racing. Craig was very, very sick, the doctor continued. He had only a fifty-fifty chance of making it through the night. The doctor promised to do whatever he could to keep him alive, but he made no guarantees.

The nurses let her into the ICU for just a few minutes that night, long enough for her to put a hand to Craig’s forehead, push some strands of hair aside, and whisper a desperate plea for help in his ear: “You’d better wake up and tell me what I need to know.”

Oscar Howard Frazier—known to all as Bud—was a tall, broad, vigorous man. He had spent so many nights on the worn leather sofa in his office at Houston’s Texas Heart Institute that he no longer noticed it couldn’t provide even a semblance of comfort. Nor did he note that his once beautiful Oriental rug, having suffered from decades of neglect, had curdled over the years to a shade somewhere between dingy beige and dingy gray. He had severely depleted the emergency wardrobe he kept in a closet in his windowless, book-lined office—a small collection of expensive ties and elegant jackets that mostly stayed in dry-cleaner bags—but he hadn’t had time to run home for more clothes. Anyway, he didn’t need them on this day. He wore his blue-green St. Luke’s hospital scrubs over an orange-and-white University of Texas T-shirt. The head of the Longhorn peeked out from beneath the neckline.

Bud’s piercing eyes were never quite visible behind the glare of his round, horn-rimmed glasses. At seventy, he had a thick mane of shimmering white hair and unlined, luminous skin that a movie star would envy, though Bud’s complexion came not from being pampered but from spending the better part of fifty years indoors at the hospital. The same was true of his hands, which were mostly free of age spots. Bud had also maintained an authentic West Texas drawl, sounding to some like LBJ on quaaludes. He lumbered a little, sometimes with a hitch in his step, the price of a high school football career, along with years of standing in the operating room for hours at a time. Most people on the street might have taken him for a college history professor instead of a world-famous cardiac surgeon, one who had done more heart transplants than anyone else on earth.

Bud sometimes wandered through St. Luke’s like a large wraith in a white coat. For decades he had traveled from his office in the Texas Heart Institute through the maze of attached hallways to visit his patients in St. Luke’s. He had a worn paperback perpetually open in his hand, often something by Shakespeare, rarely anything that could remotely be considered popular. At his age, Bud had earned certain privileges: The right to walk and read, which kept a lot of people out of his way. The right to leave towels in swirls and eddies on the floor of the private bathroom in his office. The right to check his cellphone at society galas, because people assumed he was checking on patients, and sometimes he was. During his off-hours, Bud preferred black cowboy boots, but at work he wore more comfortable shoes because surgery, especially lengthy surgeries, could be as hard on your legs and your back as it was on your hands. He’d had four operations on his back and a brand-new titanium knee put in, and he’d been glad when he was able to give up the fancy cane he’d had to use. It made pretty women solicitous, which made him grouchy.

Most people on the street might have taken him for a college history professor instead of a world-famous cardiac surgeon.

Bud’s wife, Rachel, liked to describe her husband, generously, as an absent-minded professor. But like many people at the top of their field, he had lots of folks looking after the mundane details of his life so that he could focus on his work. Bud often forgot his wallet; he did not balance his checkbook; he did not “do” email. Once, when he could not find a parking place for a gala, he parked his old Maserati on the front patio of the Houston Museum of Natural Science, barely missing the fountains. Everyone forgave him his trespasses: Bud could name, among a long list of friends and associates and patients and their family members, everyone from Mehmet Oz to Mary Karr, from Dick Cheney to Bono, from Olivia de Havilland to various Middle Eastern and European royalty. He had a long-suffering assistant named Libby Schwenke who was charged with getting him from point A to point B, whether it was from Houston to Kazakhstan or simply across the Texas Medical Center, which, unfortunately for her, was the largest medical center in the world. Even so, Bud was perennially late, famous for slipping into a party or a lecture long after it was in progress, which allowed him to be both unobtrusive and the center of attention at the same time. For Bud, time was negotiable after so many years operating on the very sick, who didn’t follow schedules either.

His life’s through line was saving the unsavable. This made Bud not just famous and respected but beloved, and not just in Houston but everywhere around the world that he had cared for sick people. Yet Bud still had one goal to accomplish before he hung it up: he wanted to see a working artificial heart become a reality, a total replacement that could be implanted and then forgotten, as his frenemy Robert Jarvik, another famous heart surgeon, liked to say. And Bud felt that he was close.

By the time Craig Lewis wound up in Bud’s care, in mid-February, he looked as if he had been incarcerated for a long time in a prisoner-of-war camp. One of Bud’s colleagues had tried to save him by putting a device called a balloon pump in his aorta to help his circulation; a kidney specialist put him on dialysis. Soon after, Craig coded—his heart stopped—and it took a team of frantic hospital personnel to get it started again.

Bud had been called in at the recommendation of another surgeon. He examined Craig and found him a challenge: he wasn’t a good candidate for a transplant, and the walls of his heart were too damaged for a traditional heart pump, something called a left ventricular assist device, which was often used in such cases. LVADs, as they were called, were Bud’s specialty, and they had become a popular option for the very sick; one tiny machine could take over the entire function of the left side of the heart, the side that did the heavy lifting, keeping the blood circulating throughout the body. In the back of his mind, Bud had another idea, but he wasn’t ready to propose it yet. He kept in touch, checking in on Craig.

Deep in the bowels of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History is a section of a storeroom with a particular set of cabinets. If you go through the proper channels, a friendly curator will let you in and, donning a pair of gloves, open the cabinets to reveal some strange and pretty unappealing-looking devices. They represent fifty or so years of attempts to make an artificial heart. Some are made of plastic, faded to the color of old chicken broth (though that’s a nice way of putting it). Others contain discolored tubes and fabric stained the color of rust or, more precisely, old blood. Virtually all of them have two parts stuck together; a few are connected with Velcro. Most have large holes on each side, giving them the look of cockeyed binoculars.

They do not look like anything a sane person would want stuck inside him- or herself. But in fact these devices represent what has been, for a long time, the holy grail of medicine: the creation of a dependable artificial heart that works on its own inside the body, just like an artificial hip or knee. Finding a cure for cancer runs a close second to this pursuit, but the fact is, heart disease kills more people around the world than all cancers combined: 17.7 million people each year, or 31 percent of all deaths. According to the American Heart Association, about 92 million Americans are currently living with heart disease or the aftereffects of stroke. Roughly 2,300 die of heart disease each day, an average of one death every 38 seconds and one out of every seven deaths in the U.S.

The number of people who die from heart attacks has fallen significantly over the years, thanks to better care and better technology, but now a greater problem is heart failure, a chronic, progressive illness interrupted with life-threatening crises. The American Heart Association’s figures show that 5.7 million people a year had heart failure in the period from 2009 to 2012, but that number jumped to 6.5 million, a 14 percent increase, in the years from 2012 to 2014. Heart transplants have become the solution of choice for disease that is beyond treatment with medication and diet and lifestyle changes, but surgeons and their desperate patients know the truth: there are only about 2,500 hearts available for transplant each year in the U.S. and, on any given day, there are roughly 3,000 people on the waiting list. In other words, there are far more losers than winners.

Meanwhile, costs are also increasing. According to the American Heart Association, the total direct and indirect price tag of cardiovascular disease in the U.S. was $555 billion in 2015, a number that includes not just deaths but lost productivity as well. And the numbers are still rising: the cost is projected to reach $1.1 trillion by 2035. That same year, nearly half of all Americans will have some form of heart disease.

It stands to reason, then, that the person who comes up with a way to replace a failing heart with an artificial one will save countless lives and change the future of humankind, much as Louis Pasteur, Jonas Salk, and Marie Curie did. And, of course, the doctor or engineer (or, more likely, the team) who figures out how to make one would likely become very, very rich. The perks, on the surface at least, look incredibly attractive, which is why inventors around the world are desperately trying to come up with a dependable artificial heart.

But just as the public is not very open to changing unhealthy habits, it’s not very tolerant of mistakes in innovation, especially when lives are at stake. There are also unique questions that have always plagued efforts to create an artificial heart. Is it ethical to spend millions on the development of a machine when preventive care could avert 90 percent of heart attacks? What would it mean if human life could be extended not just by years but by decades? How much is that worth, not only in dollars but in some undefined and unfathomable emotional currency? What would it mean to be alive but literally heartless?

Bud still had one goal to accomplish before he hung it up: he wanted to see a working artificial heart become a reality, a total replacement that could be implanted and then forgotten.

To explore the inner workings of the heart is to discover a form and a function that can inspire thoughts of the divine in the most determined atheist. It is a marvel of strength, efficiency, and tenacity. About the size of a human fist—your fist, custom-designed to your unique size—it nestles perfectly at an angle deep inside the chest, protected by the rib cage and a cushion of lungs. Weighing about eight to eleven ounces, about the same as a running shoe, it has four hollow chambers, two atria and two ventricles that look, in pictures, like ancient temples carved out of caves. Those hollows hold perfectly regulated amounts of blood. The heart also has its own system of valves, muscles, and electrical currents that make sure nothing goes wrong. In fact, it’s easy to believe in the heart as a perpetual-motion machine: it beats 60 to 100 times per minute, about 115,000 times a day, more than 2.5 billion beats in an average lifetime. Someone trying to squeeze a rubber ball at the same rate would last about a minute or two, yet the heart keeps pace continuously, whether a person is running a marathon, making love, arguing with a coworker, or getting a good night’s sleep. The heart is always there, keeping time with life itself.

For decades, artificial heart designs had mimicked the pumping action of the natural heart. The most famous of these was engineered in Houston. In 1969 world-renowned heart surgeon Denton Cooley implanted an artificial heart developed mostly in a rival lab controlled by the equally renowned surgeon Michael DeBakey (this set off one of the most famous feuds in the history of modern medicine, which continued to play out in Houston—and on the covers of national magazines—for decades to come). The patient, a middle-aged man named Haskell Karp, lived only a few days with the artificial heart. That failed experiment nearly killed the burgeoning field.

Then, in 1982, at the University of Utah Hospital, William DeVries put a heart developed by Robert Jarvik in the chest of a dentist named Barney Clark. That didn’t turn out so well either: Clark had been extremely sick with heart disease and tolerated the implantation well. But after recovering, he went into a terminal decline. By the time he died, 112 days later, the American public was not convinced that an artificial heart was a good idea at all.

There were all sorts of obstacles to developing an artificial heart that would produce better outcomes. For one, the devices left patients at risk of thrombosis, or fatal blood clots. Another obstacle was that no traditional pump, which was powered by compressed air, could equal the natural heart’s ability to beat 115,000 times a day.

By the mid-eighties, Bud had come to believe that the answer was obvious: someone had to invent something radically different. A machine that kept blood flowing through the body but didn’t use a conventional pump. That would operate continuously, without a break, for who knew how long. Maybe longer than the life of a patient lucky enough to get one.

Bud began talking about the issue with friends and colleagues, and also in public, at conferences and in papers he wrote for medical journals. There were researchers and engineers who were abandoning air-powered pumps for continuous-flow pumps, which forced blood through the body with a spinning instead of a pulsing action. But spinning blood at high speeds was known to create a condition called hemolysis, in which red blood cells break down, leading to anemia and then more serious problems, like kidney and heart failure. And, ultimately, death. Bud believed this was a problem they could solve by fine-tuning the speeds.

But another side effect of the continuous-flow device drew far more skepticism—the patient wouldn’t have a pulse. Bud’s attitude was, so what? Who said you really needed it?

The answer: pretty much everyone else in the medical community. To cardiologists and heart surgeons in particular, Bud’s idea—a pulse-less heart—was just plain crazy. But Bud believed it was the best shot at saving millions of lives. For the next two decades he devoted all of his resources to developing the device, and by 2011 he finally had a working model he felt was ready for human implantation.

As the weeks passed, Craig got progressively worse, and still no one could figure out exactly what was causing his heart issues. Linda had all but moved into the hospital, trying her best to keep her husband’s spirits up when he was conscious, making friends with the families of other patients who were fighting for their lives, shooing away the chaplain because, she said, she made her nervous.

No one told her that her husband was looking like another terminal case. Craig didn’t have a shot at a transplant: when doctors finally biopsied his heart tissue, they discovered amyloidosis, a disease in which abnormal proteins form toxic sheets in the organs of the body, eventually destroying them from within. Amyloidosis is extremely rare—the last case any doctor in Houston had seen was five years earlier—and it moved through the patient’s body with lethal speed. Trying to buy time, Bud implanted a pump called a Tandem-Heart, as a stopgap, but time was running out. Seven days was the usual limit someone could survive with such a device.

By the beginning of March, Craig had been on the TandemHeart for fourteen days, and Bud figured that even if everything went right, he had, at best, twelve more to live.

Whenever Bud saw Linda, he recognized the look in her eyes. He had seen it as a med student, as an intern, and as a flight surgeon in Vietnam—that silent plea for the impossible. It was a lonely place, being the last person standing between life and death; sometimes he could help, and sometimes he couldn’t. Even after decades as a surgeon, Bud still saw mystery in the patients he saved and the patients he lost: the question wasn’t why people died, he liked to say, but why they lived. Medicine had been practiced since the beginnings of humankind; medical libraries overflowed with tome after tome that attempted to keep pace with the ever-expanding rate of medical knowledge. Bud himself had spent more than fifty years at patients’ bedsides. But with all his knowledge, he couldn’t predict who would make it and who would not, and there had been plenty of times when he just ran out of things to offer. Linda’s look was the reason Bud had spent the better part of his life trying to come up with ways to help patients with sick hearts; he had never been able to tolerate the sense of helplessness that came over him when he couldn’t pull off a save.

Linda listened quietly, without interruption, but spoke as soon as Bud was done. “Craig’s gonna want a manual,” she said.

Now the only thing Bud had to offer Craig and Linda was a big risk—or, from the view of a dying man, not much risk at all. Late one night, Bud put in a call to Linda. “If we could just get in front of the amyloidosis,” he told her, “maybe we could buy you some more time.” A few days, weeks, perhaps even years, he just didn’t know. Then he began explaining to her, as best he could, something new he had been working on for several years with another surgeon. But he had to be honest: he couldn’t be certain it would work in humans and, if it did, for how long. It would probably benefit people in the future more than it would her husband.

Linda listened quietly, without interruption, but spoke as soon as Bud was done. “Craig’s gonna want a manual,” she said.

“You can operate on really sick people, but everything has to go right,” Michael DeBakey, one of Bud’s mentors, had told him many years ago. The warning came back to Bud as he prepared Craig for surgery.

It was a sunny spring day in March 2011, and Bud went to work in St. Luke’s largest operating room. Unlike virtually everyone else around him, he was calm. He had been there many times before.

A heart-lung machine had already taken over for Craig’s damaged heart. He was covered from head to toe, except for a hole where an associate had opened up his chest, so that his heart sat exposed, barely beating, the color of rotting meat. There were so many tubes and wires coming in and out of Craig’s body that a less experienced surgeon might have been terrified of tripping. But Bud and Billy Cohn—a surgeon-inventor who had worked with Bud and a team of engineers on this experimental device—moved about effortlessly and economically, never quite standing up to their full height as they focused on the patient on the table. Cohn was responsible for cracking the jokes. Bud chuckled, whether he found them funny or not.

Bud began by cutting out almost all of Craig’s heart. His hands, encased in yellow gloves, grew redder with blood by the minute as he snipped away at the arteries and veins holding Craig’s heart in place, until finally he lifted the organ out of Craig’s chest, casually handing it to a nurse who unceremoniously put it in a basin for pathology. And then Bud and Cohn began stitching their artificial heart into Craig’s body. Bud could feel a small crowd of doctors and nurses leaning into the skylight in the viewing area above him. But he never looked up, not once. The entire operation took about nine hours.

Relatives of patients are not allowed to watch loved ones’ operations, so the first glimpse Linda got of her husband was when she entered his recovery room. Craig was surrounded by wires and tubes, feeble but alive. Within a week he was sitting up in bed, tapping away on his computer.

Curious about the device inside of Craig, Linda leaned in one day and put her ear to his chest and waited. Then she shifted her body so that she could press just a little harder. There was almost nothing to hear. No thump-thump, no heartbeat, just a faint whirring somewhere deep down inside.

The machine was working perfectly. The question was: How much time would it buy him?