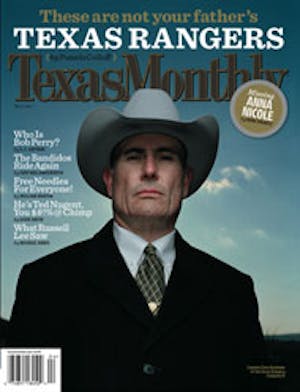

NO SOONER HAD THE INK DRIED on Governor Rick Perry’s executive order to require all sixth-grade girls in Texas to be vaccinated for human papillomavirus (HPV)—the cause of deadly cervical cancer— by next school year than a firestorm erupted in our newspapers, blogs, and the halls of the Capitol. The initiative, the first of its kind in any state, contained three terms that tend to make many Texans uneasy: “vaccine,” “sexually transmitted disease,” and “cancer.” Then came “government,” “mandate,” and “sixth-graders,” and all hell broke loose. By now you’ve heard every shade of the rhetoric: On the upside, Perry’s order pioneers a cancerless future for all women; on the downside, it violates parental rights, might encourage promiscuity, and represents a shady relationship with Merck, the vaccine’s producer. You’ve also witnessed some of the fallout: A House bill has been filed to rescind the mandate, Merck is halting its lobbying efforts, and, oh, there’s a lawsuit against Perry. But amid all this hoo-ha, you’ve probably heard little (or little that’s clear-cut, anyway) about the actual science involved. What is the HPV vaccine, really? Here’s a look at one of the most important public health initiatives promulgated by Texas in recent memory.

First things first. What is HPV and how does it cause cervical cancer?

HPV is actually a collection of about one hundred viruses, thirty of which are passed via sexual contact. Of those thirty, two cause 70 percent of cervical cancers (an additional eleven viruses are responsible for the rest), and two others cause 90 percent of genital warts. The remaining, non-sexually transmitted viruses are passed by other human contact—say, shaking hands—and are generally asymptomatic, though some can result in warts on the hands and feet. The viruses apparently derange the DNA in the epithelial cells of certain mucosal tissues, principally those of the cervix, vagina, and anus, thus causing cancer. HPV is the most common sexually transmitted disease in the U.S.—it generates about six million new infections a year—and it is estimated that 20 million Americans (men and women) carry an active infection at any given time. Seventy-five percent of women will have some form of the virus during their lifetime.

How is cervical cancer normally detected?

With an annual Pap test. Since its introduction in the fifties, this screening for HPV and its precancerous cells has reduced the incidence of mature cervical cancer by 75 percent. A Pap catches cancers from all HPV strains—no woman should forgo one, as unpleasant as it may be—but it’s not a cure or a prophylactic. Which is why Merck’s vaccine (as well as one anticipated from Glaxo-SmithKline next year), which targets the four most pathogenic viruses, has public health officials so excited.

So what is this vaccine?

Available since last June, it’s called Gardasil—and it is not, as you might have read on some blog, composed of live HPV. Merck produces it by transferring the genes that contain the code for certain key proteins in those four viruses to yeast, where they express said proteins, and then by suspending these in an injectable fluid. Once integrated into the body’s physiology, these proteins train the immune system to recognize and destroy the viruses. The vaccination requires three shots over a six-month period; the company’s best guess is that it will be effective at least four years.

How about the cost? I’ve read that Gardasil is prohibitively expensive.

Merck claims that 96 percent of health insurance carriers cover it, but predictably, it’s not that simple. Many pediatricians have complained that insurers are not reimbursing them sufficiently to make it worth their while to stock the vaccine, a complaint they’ve had about other vaccines as well. So some have refused to buy the stuff, while others are charging a premium: The three shots cost $360, but a patient may have to pay upward of $450 to cover storage and office costs. Those families who qualify for Medicaid can obtain the vaccine free through the Vaccines for Children program, if supplies hold up. Bottom line: Have a good long talk with your doc about costs and coverage before you commit.

But I’ve also heard that there hasn’t been enough research done on the vaccine, especially among preteens.

Merck has tested the inoculation on nearly 11,000 females between the ages of 9 and 26 over five years, and it has achieved an almost 100 percent efficacy in warding off the virus in those women who were not already infected. (Among those infected with one or more of the targeted viruses, the vaccine will still protect against the ones the patient has not contracted.) While Cathie Adams, the president of the conservative issues advocacy group the Texas Eagle Forum, argues that this isn’t enough testing, she stresses that she’s more concerned about Perry’s order—forcing a vaccine on Texas parents before they know enough about it—than the science. “If parents want to get this vaccine for their daughters, they can,” she says. “I’m just against the mandate.” Meanwhile, Maurie Markman, the vice president for clinical research at the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center and a specialist in gynecological cancers, told me that he finds the research “very compelling. We could not have hoped for a better outcome. The number of subjects and duration of follow-up were adequate.” He added that Gardasil has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (which has a rigorous process of review), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the American Cancer Society—which is pretty much as endorsed as a medication can get.

Haven’t some clinical trial subjects suffered terrible side effects from the vaccine?

This allegation has popped up a lot on the Internet, particularly at the site for something called the National Vaccine Information Center, a watchdog group. These folks seem to imply that Gardasil causes arthritis and lupus, among other things, because Merck’s trial study documents include those conditions in describing some of its test subjects’ health. But FDA licensing documents for the vaccine indicate that these were primarily preexisting conditions and that the vast majority of side effects involved pain at the site of the injection, nausea, dizziness, and fever—not uncommon reactions to any vaccination.

What about the concern that receiving this sort of immunization will encourage girls to be sexually promiscuous?

STDs have always served as a valuable tool for the abstinence lobby—HPV has been especially handy because it can be contracted even when condoms are used—so this opens all manner of charged debate. Of course, from a scientific perspective, there’s no way to prove that inoculating young girls against an STD will encourage promiscuity. As Markman put it, “This isn’t about sex. This is about preventing cancer.” Perry echoed this recently in The Economist : “If the medical community developed a vaccine for lung cancer, would the same critics oppose it, claiming it would encourage smoking?”

But why does it have to be mandatory?

Ah—by far the most common complaint from social conservatives, parents, and doctors’ groups alike. It’s understandable: Historically, most vaccines—mumps, measles, polio, and so on—have rested their mandates on the policing power that states have over public health (as they do over safety and security), because those infections were easily passed from child to child, especially at school. But the HPV vaccine inoculates against a virus acquired largely through a volitional act—generally, sex. Thus the debate is hardly over: Though Perry included an “opt out” clause in his executive order (any parent who doesn’t want his daughter to receive the vaccine based on religious grounds or other reasons of conscience can submit a written form and be free of the mandate), there are those, like Adams, who claim that the process to reject the vaccine is too onerous (the form must be notarized and resubmitted every two years) and that the state should instead institute an “opt in” procedure for parents who want their daughters vaccinated. Others say that an opt-in measure would just confuse or otherwise discourage poor and undereducated families from participating. So what will Gardasil’s fate be? Stay tuned. Now that the Legislature is involved, this could take some time.