This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Beach Bait

Two hundred tons of sand help fill one apartment complex.

Bob Park likes the palm trees, the palapa, and the white-sand beach. On weekdays he often lounges there before heading to his evening job as a computer operator. He also likes the weight room, the security fence, and the pool. Most of all, he likes the rent at the St. Gregory’s Beach apartments just off Highway 6 in northwest Houston. “For the price,” he says, “I just couldn’t beat it”—an even $200 for a one-bedroom apartment. That is just $10 a month more than he had been paying for a recently burglarized efficiency that was two hundred square feet smaller.

Apartment rents are a gauge of economic vitality because they telegraph when developers can build new apartments. It is a good omen for Houston that rents are finally going up; it is a bad omen how low they have sunk. Most renters can live somewhere nice for about what it costs them to live somewhere not so nice, creating what local real estate types call a “flight to quality.” The surviving apartments in the fierce competition for tenants are those with some edge or gimmick. That’s why Houston-based Arruth Associates spent half a million bucks revamping the 186-unit complex where Bob Park lives, bringing in 200 tons of beach sand, 150 palm trees, and myriad hibiscuses and oleanders. The occupancy rate at St. Gregory’s has gone from 35 percent to 90 percent in less than a year.

If landlords are at a disadvantage vis-à-vis tenants, they have the upper hand in dealing with lenders, which is why Arruth Associates could afford to spruce up St. Gregory’s. Thanks to foreclosures, banks own many—too many—of the apartments in Houston these days. To entice buyers, they must agree to forgo interest payments when market rents are too low to make a profit, as is the case today. Lenders and buyers alike are betting on the future. If they can fill their apartments now, they can raise rents as the recovery creates more jobs, bringing to Houston more people who want to live in apartments.

Bob Park can see it happening, and he is under no illusions. He expects that before long, his rent will go up.

Tom Curtis

The Last Condo

At a highly visible symbol of the bust, folks are finally buying.

It was the thirty-ninth—and last—entrant among Houston residential high rises, the final splurge of the boom. The Spires, a forty-story condo, was built on the southern fringe of the metastasizing Texas Medical Center with commanding views across Hermann Park to the downtown skyline. When it was finished late in 1983, it faced not only a surfeit of competitors, like the Bristol, the Greenway I and D, and 5000 Montrose, but also a shortage of buyers who had money to spend. In the first year only 13 of the Spires’ 230 units sold.

Ultimately the owner, Canada’s Campeau Corporation, bowed to the inevitable and rented out the empty units, using inducements like one month’s free rent and monthly tariffs as low as $850 for two bedrooms. Last year Campeau swallowed a $20 million write-down on the property. Finally last summer the company began what amounts to a half-price sale, offering units once priced at $160,000 to $400,000 for $79,000 to $240,000. Without advertising to the public, Campeau sold 43 units in the two months ending in mid-October. (Meanwhile, in a calculated gamble, Campeau is hiking rents $200 to $400 per month as leases expire—much to the outrage of current tenants.) It is enough to make an optimist of Wayne Jones, the recently installed vice president at Campeau High-Rise Homes of Texas, the condo-selling subsidiary. “Two years ago,” he says, “people wouldn’t have bought at any price.”

T.C.

Phoenix Rising

Occupancy goes from zero to 60 percent in eighteen months.

The 34-story Phoenix Tower on the Southwest Freeway was an easy mark for photographers who wanted a symbol of Houston’s economic collapse. From the building’s completion in 1984 through the spring of 1987, the green-glass office project stood egregiously empty—a “see-through” building. In 1986 the developer, Allegheny Realty, unloaded the 600,000-square-foot, $60 million albatross at a 25 percent loss.

The new owners—Homart Development, a Sears subsidiary—spent a year and $2 million spiffing up the place. It junked Allegheny’s policy of refusing to lease less than 100,000 square feet (upwards of four floors) to any single tenant. Fellow Sears subsidiary Dean Witter became the first tenant in May 1987, leasing just 15,000 square feet. Now the building is 60 percent occupied. Normally that occupancy rate would move the owners out of the red, but not in the buyer’s market that is today’s Houston. To get tenants, Homart had to offer below-market monthly rents of less than $10 a square foot. United Savings, which took almost 100,000 square feet, forced Homart to pay moving costs and buy up its old leases as well.

“I’d like to say we’re at the end of serious concession packages, but we’re not,” says Carolyn Christian, the Homart official in charge of filling up the building. Not until the building is fully leased, sometime in the far future, will it have a positive cash flow, she says. No longer empty, Phoenix Tower continues to reflect Houston’s economic condition. “The recovery isn’t here yet,” Christian says, “but it is on the way.”

T.C.

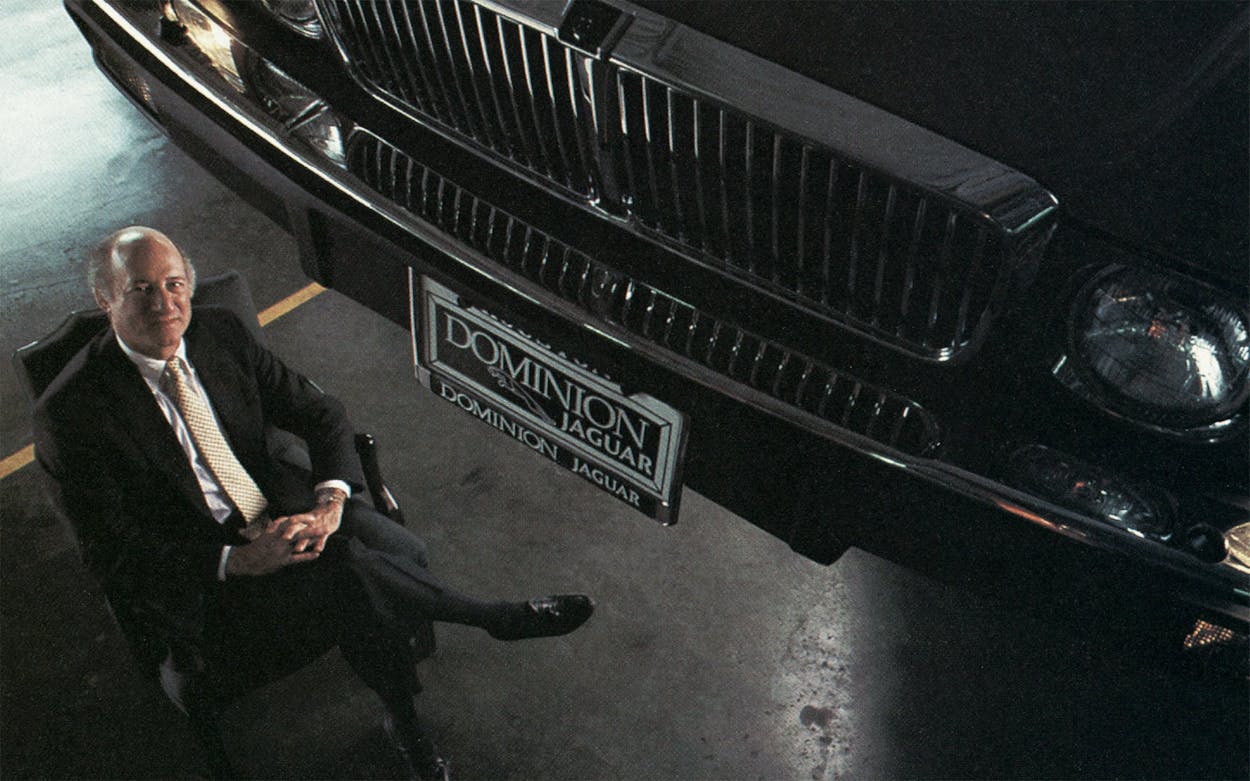

On a Jag

A land developer finds an investment that actually moves.

Most places in the U.S., Mercedes outsells Jaguar four to one. In Houston the Mercedes advantage drops to only two to one. That greater Jaguar popularity fits. The Jaguar is the perfect upscale car for the new lean, mean Houston: It is sleek and stylish and looks more expensive than it is. The best-selling model, the XJ 6, goes for around $43,500—roughly $10,000 to $20,000 less than the popular Mercedes 400 and 500 series cars.

The owner of Houston’s Jaguar dealership for the past two years has been commercial real estate developer David Wolff, whose franchise amounts to an eight-county monopoly. Wolff, who developed Park 10 and other Houston business parks, is that rare bird among Houston developers—a nonbankrupt. He was, he notes, one of the few among his erstwhile brethren who “always had an essentially pessimistic outlook,” assumed Houston’s real estate bubble would eventually pop, and planned accordingly. Instead of accepting 100 percent liability on his deals as John Connally and others did, Wolff generally limited his liability to 20 percent. He developed only in Houston and did not join the frenzy of Houston developers who left the busted city to frantically overbuild other soon-to-crash cities like Austin. That cautious strategy has made Wolff enviably liquid, with $30 million or so in financial assets to manage, plus $100 million in real estate and a wealth of potential investments to consider (he hopes, for instance, to acquire a professional sports franchise).

So far, about the only business that has intrigued Wolff enough to buy has been auto dealerships (he also bought a southwest Houston Volvo-Subaru franchise). The dealerships seemed undervalued compared with their profit potential. Wolff’s Dominion Jaguar each year sells around 450 new Jags and 200 used ones for annual sales of around $25 million (his two dealerships gross about $60 million a year). The figures represent a 12 to 14 percent return on investment annually in soft times like the present and maybe 20 to 30 percent when the economy firms up. That’s not the 80 percent annual return on land that Wolff had grown used to. Then again, it’s significantly better than the zero percent developers are racking up today.

T.C.

Feathering His Nest

A California vulture cleans up in Houston.

A year and a half ago a California investor named Maxwell Drever peered out of a helicopter above Houston and searched for signs of a break in the lingering bust. He noticed that a number of manufacturing plants were in the early stages of expansion. Since Houston’s snakebit banks were reluctant to lend, he knew that the signs of life below were being financed the hard way—out of cash flow. That meant the time had come to start buying.

Drever runs what are known in the trade as vulture funds—pools of capital that scavenge in a lifeless economy. In Houston as in the ecosystem, vultures are necessary to clean up unsanitary messes no one else will touch. Vulture funds have three things Houston needs desperately: money, faith in the future, and the willingness to take a long-range view.

Every week or two Drever—a lean six one, with a prominent nose, a bow-tie ruff, and a charcoal Brooks Brothers suit—leaves San Francisco to swoop down upon Houston. He searches for badly run, poorly maintained apartment complexes that he can buy for one third to two thirds of the cost of new construction. He fixes them up with a coat of paint, landscaping a grade higher than the competition offers, and a wrought-iron security fence, and he keeps tenants happy with weekend amenities like free car washes, free towels at poolside, and free manicures.

Drever offers investors a 12 percent or better annual return on his Houston properties. But he thinks he can do much better—a 20 to 30 percent return on investment. In the seventies and eighties he averaged 29 percent selling off complexes he had picked up in Dallas, Denver, Tampa, Seattle, and Columbus, Ohio. But being a vulture is a risky business. “If oil goes down and stays down, we’ll be in the same soup as the people we’re buying from now,” he acknowledges. “By the grace of God, we didn’t buy here in ’84 and ’85, when all the national syndicators thought Houston was coming back.”

On the Thursday after Labor Day Drever rides shotgun and fields phone calls as Joe Gillespie, his Houston acquisitions manager, threads a Eurostyle black Lincoln through heavy northwest Houston traffic. Drever likes the area, despite such grim evidence of glut as banners promising two months’ free rent. Northwest Houston is close to Compaq Computer Corporation and has new shopping centers, improved arterial streets, and a toll road offering quick access to downtown. Most of the eleven Houston complexes (with 2,715 units) Drever has purchased are in this area. He aims to buy another 1,000 to 2,000 units this fall.

Gillespie, a short, blocky man who plays Mutt to Drever’s Jeff, steers the car into the parking lot of a 144-unit B-minus complex off FM 149 for which Drever has a signed letter of intent. The place is un-landscaped but neatly kept, the purchase price is attractive—$16 a square foot—and the manager tells Drever the property is 96 percent leased, mostly by “poor people,” at rents averaging 35 cents a square foot ($195 a month for a small one-bedroom apartment). The property is an obvious casualty of the bust: In 1984 it was on the market for $4 million, later the asking price fell to $3.2 million, and now the owners will take $2.2 million.

Drever quizzes the young woman manager about the complex and the neighborhood and is told that nearly half a nearby residential area is black. He compliments her on keeping the complex so tidy, the manager beams, and Drever climbs back into the Lincoln. “When she told me about the neighborhood, that killed it,” Drever says. “Investment capital has no heart,” he had explained earlier. Drever sees it as business, not bigotry: a neighborhood shifting from white to minority means prices of nearby property may drop, not soar. That makes the property a bad bet for appreciation.

A pricier prospect is Central Park Regency, a five-year-old 348-unit complex offered by its builder-owner for $9.1 million. With Drever’s expression of interest, the seller signs a letter of intent on the spot. But the place eventually fails inspection and turns out to be one of the many deals Drever rejects.

On the way to the airport Gillespie tools past three or four other potentials plus an apartment complex called Cypress Landing that Drever has bought and is repainting in salmon with a cream trim. He is also adding lattice work, shutters, and landscaping. Things are coming along nicely at the 464-unit property, on which Drever is spending $3,000 a unit to upgrade. The occupancy rate, which was 60 percent at rents of 27 cents a square foot, plunged to 45 percent when the management evicted tenants who were tearing up the place. Now occupancy is climbing above 60 percent again, even with rents boosted to 34 cents a square foot. Years from now, when the complex fills up and rents hit 65 cents a square foot—which is higher than rents were at many nice apartments during the boom—Houston developers will begin building apartments again. When they have built too many, Maxwell Drever will cash in and go find himself another bust town.

T.C.

Shop Till You Drop . . . Millions

Houston’s newest mall wants to be all things to all rich people.

On the Houston retail scene, Pavilion Saks Fifth Avenue may be the most extravagant monument to date to the belief that the worst is over. Once a hulking, somber shopping mall situated demurely in a grove of oak trees—just north of the Galleria and across from Tony’s on glitzy Post Oak Boulevard—it is today, thanks to a $20 million renovation, a hulking, gleaming shopper’s oasis that could double as the capital of a Third World oil-rich nation. Pavilion Saks Fifth Avenue is a lavish testament to the slowly recovering economy—Houston’s 1988 first-quarter retail sales are back up to $6.1 billion after a dip to $5.5 billion in 1987.

The epicenter of the much heralded recovery is in the three-square-mile Galleria–Post Oak neighborhood, known in better times as the Magic Circle. Sales in the area may have dropped from a boomtime high of $450 a square foot to around $300, but that number is still a robust $150 above the national average. “Sales in this area don’t have to go up to be good,” says Pavilion general manager Charles Cox. “They just don’t have to go down.”

Sanguine retail investors have made an important discovery: Even in the slow economy, catering to the rich can be lucrative. “The affluent Houstonians are still here,” says Cox, “and they’re still affluent. They still spend money, and they still enjoy life in Houston.”

At least, that was the thinking of Pavilion’s new owners, Boston-based pension-fund managers Aldrich, Eastman, and Waltch, when they bought the ten-year-old center from British Airways in 1984. Compared with the Galleria, Houston’s preeminent shopping mall, the then-named Saks Center of Fashion was an austere New York temple of style buttressed by high-toned European shops. The number of shoppers didn’t matter so much in good times—the customers who came had money to spend, and spend it they did. But when hard times hit, those shoppers vanished (“You could shoot a cannon through the place and never hit anyone,” a former tenant noted). Aldrich, Eastman, and Waltch hired Dallas developer Kenneth Hughes, and, as quick as you can say “betting on the come,” Pavilion—the only major new shopping center project in Houston today—was born.

Hughes’s plan included increasing the space to 290,000 square feet and replacing the mall’s square shape (Saks was in the middle) with a churchlike nave-apse structure. The ascetic slate floors were replaced with a warmer Arizona sandstone, severe corners were softened with soaring arches, and oaks were replaced with ninety palm trees of varying heights. Gurgling fountains were imported from Italy to break the center’s museum-quality silence. Casual elegance was the rule: “We want to be a shopping resort,” says Cox, “a place where women can walk through in their leotards.” If all goes well, Pavilion will have some of the most exclusive retail outlets in town (designers like Ungaro and jewelers like David Webb), along with security guards in red jackets, underground parking, valet parking, and—the latest thing in mall design—exterior as well as interior entrances for stores, so that “destination-oriented shoppers” (new buzzwords meaning shoppers headed for only one store) don’t have to battle their way through hordes of hoi polloi.

For all Cox’s talk of recovery and renewed confidence, Pavilion is, in fact, moving in on a perceived weakness in its main competitor, the Galleria. Since it opened eighteen years ago, the Galleria has had a lock on upper-end retail in Houston. It had the Euroshoppers, the Mexicans, and the Japanese as well as River Oaks matrons and Midland oilmen. Then came the bust—and several expansions—and a more egalitarian Galleria was born. Luxury stores like Gump’s and Neiman’s were keeping company with more and more chain stores while wealthy clients had to dodge gum-snapping teenagers to make their purchases. Although Galleria manager Leah Thayer of Gerald D. Hines Interests insists that this new mix has helped sales—some stores are up 20 percent—Cox is not so sure. “Affluent customers don’t enjoy the biggest centers,” he contends, propounding a rapidly spreading developers’ myth, the subtext of which is that the Galleria is too crowded and too, well, democratic.

It isn’t just Pavilion’s fancy face lift that is attracting tony clients, of course. Rents in the Galleria are around $30 per square foot (down about $10 from boomtimes but pricey nevertheless); Pavilion, eager to fill up the mall, is charging a bargain rate starting in the $18 to $20 range. It is also offering extremely generous build-out allowances (the money a mall contributes to the tenants’ interior design)—twice what the Galleria offers, in one case at least. And it isn’t just the Galleria that Pavilion is fighting; it has also taken on Highland Village, a fifties low-rise center that straddles four blocks on Westheimer adjacent to River Oaks. Ever since Mickey Rosmarin moved his Tootsies boutique into the refurbished center from the Galleria area three years ago, Highland Village has gone from sleepy to sophisticated without abandoning its neighborhood loyalty.

Competitors have responded to Pavilion’s challenge. Galleria management, which never had to display much flexibility in the past, showed its accommodating side when Tiffany’s manager Sharon Seline let it be known she was considering a move. Highland Village and Pavilion tried to woo her away, but ultimately Seline elected to stay put after the Galleria came through with an offer to provide valet parking—at Tiffany’s expense. “Our customers don’t want to be inconvenienced,” asserts Seline. “Our customers will not be inconvenienced.” Nor do most retailers want to forsake the Galleria—and its volume—if they can avoid it.

But can catering solely to the whims of the wealthy really provide a shopping center with the profits it needs to survive? Certainly precious few retailers are taking the improving numbers for granted. Sure, Mickey Rosmarin has expanded Tootsies with a men’s shop and a freestanding salon for his finest clothes. But like many upper-end retailers, his once-extravagant merchandise is now merely expensive—he has downscaled—and, like many of his competitors, he keeps a sale rack tucked away discreetly in the back of his store.

So far, the battle among the upper-end centers amounts to a retail round-robin, as stores gravitate to centers that seem to suit their identities. Along with David Webb, the Italian retailer Caruggi has left the Galleria to reopen in Pavilion. Ralph Lauren’s Polo store, which never lived up to its potential in Saks Center, has moved to the Galleria, where sales are up. Lynette Proler’s antique-jewelry business improved after she moved from the Galleria to Highland Village.

One thing retailers agree on is that the good times will return but the great times are gone forever. “We’ve just come back to normalcy,” explains retail-leasing executive Don Connelly. “And normalcy is where we should be.”

Mimi Swartz

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Houston