For three weeks in a row Mrs. Webster’s second-grade class had surpassed the rest of the school in the observance of Quiet Thursday. They were an exceptional class: docile, good-humored, still wrapped in that cocoon of bemusement that protects children, in the first few years of school, from any knowledge of how grave and exacting an institution it is. But Mrs. Webster did not really expect them to win Quiet Thursday again. It was May now, there were only three more weeks of class, and every day that the students came to school they seemed to bring less of themselves. Poised on the edge of summer, the world outside Thorndale Elementary was one great shimmering distraction: Six Flags Over Texas had seized the airwaves and implanted in every preadolescent soul in the state an unbearable longing for what the park was billing as nothing less than a perfect world; Slime, a packaged green ooze with no practical application, had just come onto the market; and there were rumors of a new form of candy that, once ingested, produced dozens of tiny explosions in the esophagus.

For three weeks in a row Mrs. Webster’s second-grade class had surpassed the rest of the school in the observance of Quiet Thursday. They were an exceptional class: docile, good-humored, still wrapped in that cocoon of bemusement that protects children, in the first few years of school, from any knowledge of how grave and exacting an institution it is. But Mrs. Webster did not really expect them to win Quiet Thursday again. It was May now, there were only three more weeks of class, and every day that the students came to school they seemed to bring less of themselves. Poised on the edge of summer, the world outside Thorndale Elementary was one great shimmering distraction: Six Flags Over Texas had seized the airwaves and implanted in every preadolescent soul in the state an unbearable longing for what the park was billing as nothing less than a perfect world; Slime, a packaged green ooze with no practical application, had just come onto the market; and there were rumors of a new form of candy that, once ingested, produced dozens of tiny explosions in the esophagus.

Against all this the teachers at Thorndale could only fight a holding action. They threw everything they had into the breach: arts and crafts, track meets, faded filmstrips from the fifties on bicycle safety. Every so often they would make a V-sign with their fingers and wave it in the air, but this symbol for silence went largely unremarked. All their Quiet Thursdays seemed to be behind them. At this point, the popcorn the kids were being offered for their silence just wasn’t enough of a bribe anymore.

“I don’t believe this,” Mrs. Webster said when her class broke ranks on the way to the cafeteria. “You’re one of the best classes I’ve ever had going down the hall, but now you’re acting like first-graders. I want you to turn around and go down to the end of the hall and come back quietly!”

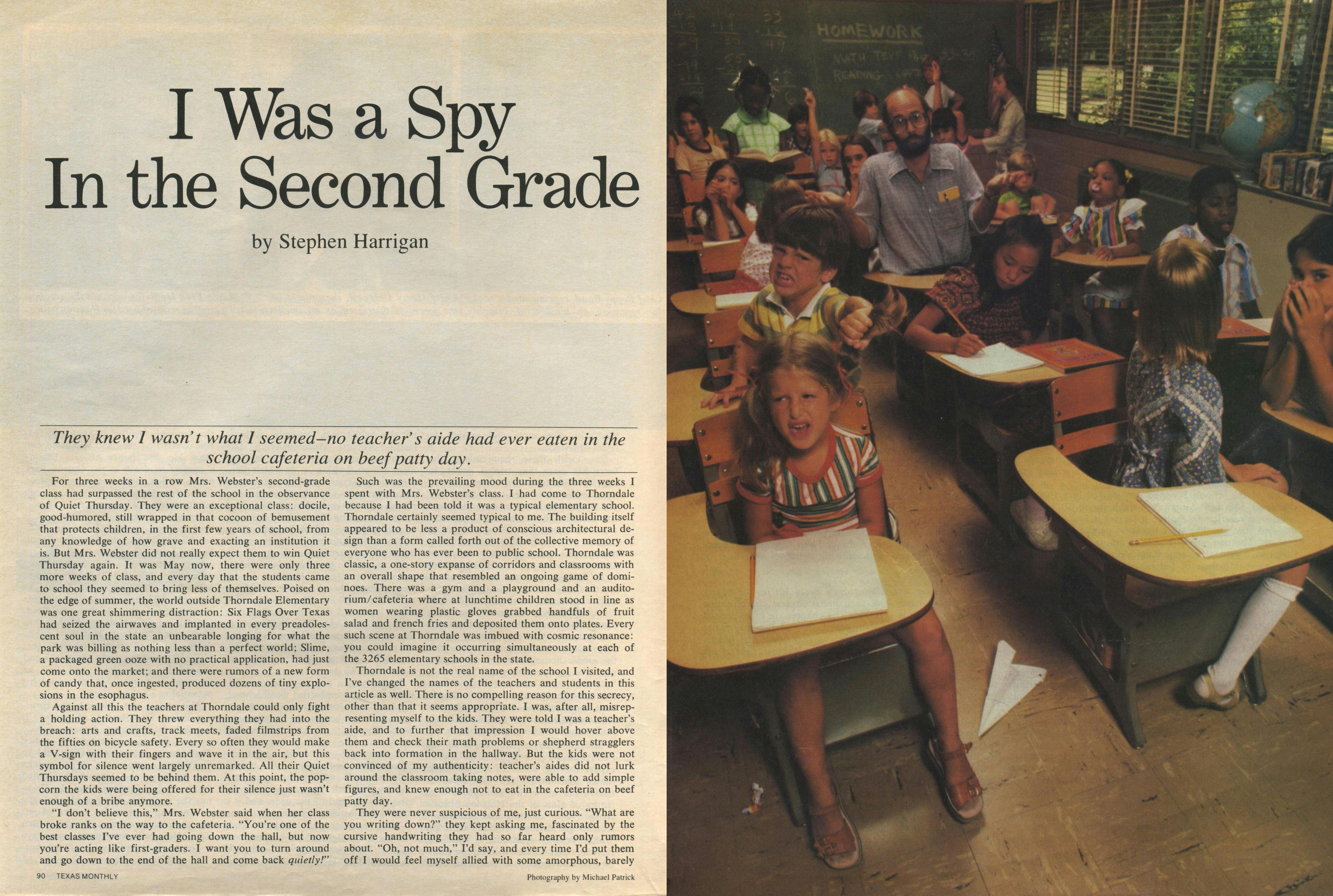

Such was the prevailing mood during the three weeks I spent with Mrs. Webster’s class. I had come to Thorndale because I had been told it was a typical elementary school. Thorndale certainly seemed typical to me. The building itself appeared to be less a product of conscious architectural design than a form called forth out of the collective memory of everyone who has ever been to public school. Thorndale was classic, a one-story expanse of corridors and classrooms with an overall shape that resembled an ongoing game of dominoes. There was a gym and a playground and an auditorium/cafeteria where at lunchtime children stood in line as women wearing plastic gloves grabbed handfuls of fruit salad and french fries and deposited them onto plates. Every such scene at Thorndale was imbued with cosmic resonance: you could imagine it occurring simultaneously at each of the 3265 elementary schools in the state.

Thorndale is not the real name of the school I visited, and I’ve changed the names of the teachers and students in this article as well. There is no compelling reason for this secrecy, other than that it seems appropriate. I was, after all, misrepresenting myself to the kids. They were told I was a teacher’s aide, and to further that impression I would hover above them and check their math problems or shepherd stragglers back into formation in the hallway. But the kids were not convinced of my authenticity: teacher’s aides did not lurk around the classroom taking notes, were able to add simple figures, and knew enough not to eat in the cafeteria on beef patty day.

They were never suspicious of me, just curious. “What are you writing down?” they kept asking me, fascinated by the cursive handwriting they had so far heard only rumors about. “Oh, not much,” I’d say, and every time I’d put them off I would feel myself allied with some amorphous, barely perceptible conspiracy against them. In an institution of learning my instinct had told me to withhold information, that I was here not so much to impart knowledge as to forestall chaos, so that knowledge could be calmly and evenly dispensed.

It was not the first time I had confronted my capabilities as an educator. Several years earlier I had worked for the state’s Poetry in the Schools program with fourth- and fifth-graders. Week after week I watched the class I was teaching degenerate into a mob. For every girl who would shyly hand me a poem about horses dancing at the North Pole there would be two boys in an all-out fistfight in the corner.

“Uh, why don’t you write a poem instead?” I would suggest.

Sure. Finally the librarian or, on occasion, the principal, would peer in through the door with a look of such deep shock that the offenders would settle down for a few moments and grudgingly dash off a poem about shark fishing or car upholstery.

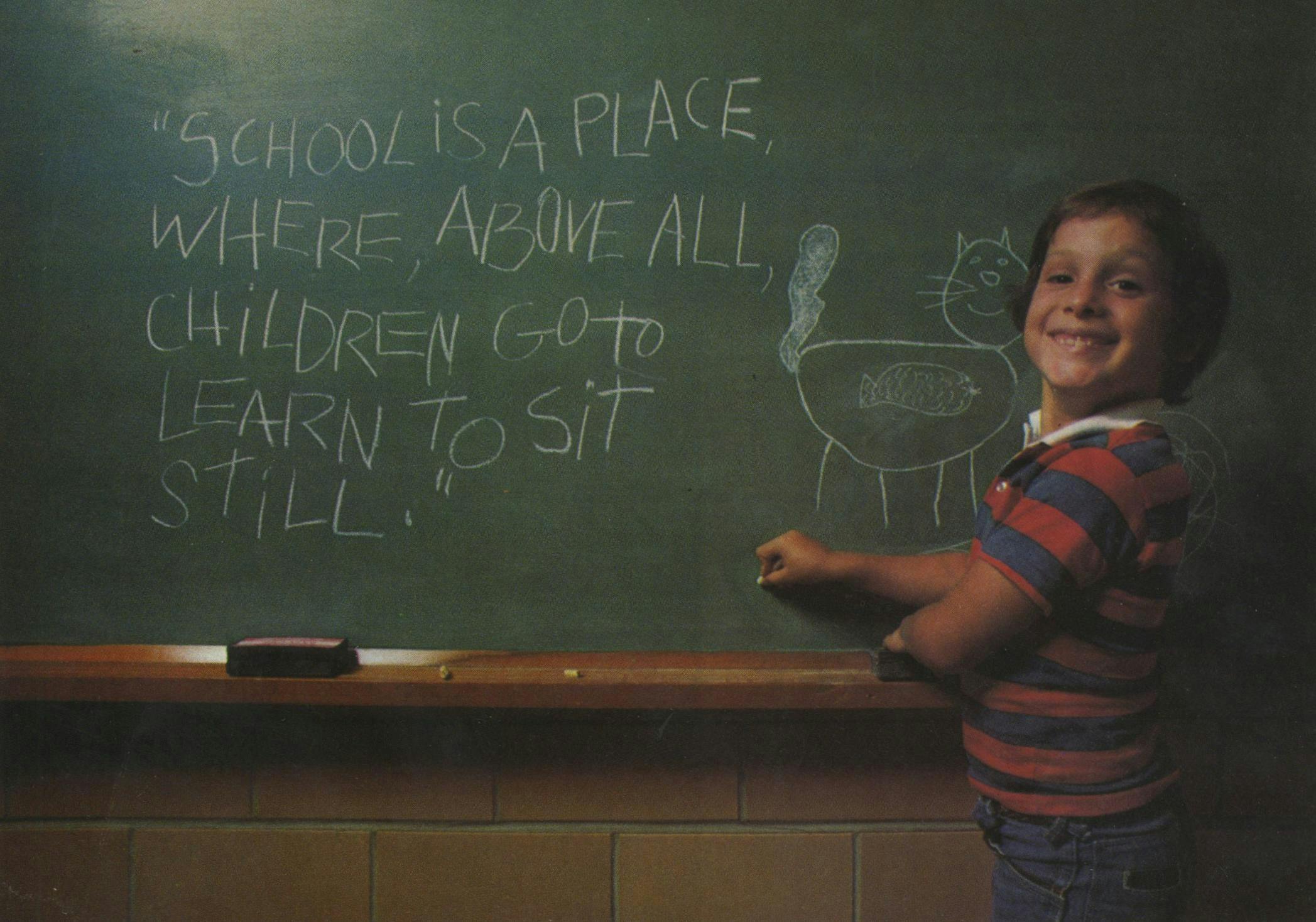

I had come home every week shaken and exhausted after only an hour in the classroom, struck with the realization that if one was to be an effective teacher in a public school, one had to make peace with the fact that education was an enterprise that was conducted under martial law. School was a place where, above all, children went to learn to sit still.

There are, of course, different settings for this experience. Before coming to Thorndale I had visited several other schools within the same district. Though each school receives from the district a standard per capita budget, they differ widely in supplemental income. Various factors contribute to this. In a wealthy community, an affluent and cohesive PTA can make a great deal of difference, providing the school with a surplus of electronic learning devices and applying pressure to insure that its teachers are calm and cheerful and never speak above a well-modulated whisper. Though these schools are not eligible for the federal money that poorer communities receive under the provisions of Title I, they often have a staff experienced in writing grant proposals and pilot projects.

One of the schools I visited was located in a financially depressed Mexican American neighborhood. It had been built a year earlier to replace a facility a few blocks away that had been standing since the latter part of the nineteenth century. The new school had been constructed with money raised by a general revenue bond election and was operated with heavy infusions of federal aid in addition to the district’s allotment. It was a showcase, built in the Open Classroom concept (everything having to do with education is a “concept”)—a big, brightly lit windowless place that reminded me of a shopping mall. An ersatz pre-Columbian mural loomed in the entrance hall, and at the core of the school’s one great room was a sprawling library, around which eight classes were conducted simultaneously in English and Spanish. The open school itself, however, had been subdivided by bookshelves and audiovisual equipment thrown up between each instruction area. These makeshift classrooms were the most promising thing about the school: they suggested a human encroachment in a theoretical environment. The open classroom was being reclaimed.

Within these enclosures highly skilled teachers spoke to their students in low, sober tones.

“Sandra, I like it so much better when you’re sitting in your seat working. Thank you.” “It’s so much fun when everyone works on their reinforcement skills together. It would be so much better if David and Gracie would join us.”

“The discipline problem has diminished tremendously since we moved into this facility,” the principal assured me, and I had no reason to doubt him. The children seemed subdued and content, motivated, if not inspired, by the dispassionate talents of their teachers.

But this school was an exception. Within the same district there were other schools still housed in grim, decrepit buildings dating from eras in which any educational concepts were simple and absolute. For schools in low-income areas the district lowered the standard student-teacher ratio (from 28 to 1 to 22 to 3) and federal money still paid some of the bills; nevertheless they could be bleak places. I visited a classroom in which twenty black second-graders were being shown vowel sounds on an overhead projector by a kindly white woman from another planet. The harsh light of the classroom, the dark, narrow corridor outside, the smell of mildew and the acrid composite odor of the food being prepared for lunch contributed to a palpable mournfulness. Unlike their contemporaries at Thorndale, these children seemed already to have sensed the magnitude of this enterprise and had resigned themselves to it. School was a chronic condition that would never end.

“Now boys and girls,” the teacher was saying, and her voice was naggingly familiar, like a long-forgotten voice heard at a séance, “if we get our work done, if we don’t get any names taken in the lunchroom, it wouldn’t surprise me at all if we got to go outside for a little bit. But not if we touch each other or bother each other in any way . . .” Thorndale was not so oppressive. It was, I thought, a pleasant school, an environment the children took for granted, a place where they existed with proprietary ease. The school’s population was mostly white, gleaned from a community of mixed fortunes. The Thorndale school zone incorporated the children of lawyers and professors and consultants who lived in a fashionable neighborhood along the banks of a creek, but were too far upstream to send their children to a nearby school where a progressive PTA had bought a synthesizer for the music room and hung Cezanne and Van Gogh reproductions in the halls. The larger part of the Thorndale zone was economically depressed, a neighborhood of dilapidated rental properties where families lived month by month with the possibility of eviction.

There were children in Mrs. Webster’s class who were wards of the state because at home their parents had routinely beaten them, and there were others whose parents abused them no further than taking them out to expensive restaurants and making them try escargots.

It was not immediately apparent to me which kids were which. The class, as a whole, was homogeneous, a single organism that had an embryonic promise about it. For the first few days I was there the children seemed to me unformed, unimpressed, as touchingly indistinct as a litter of kittens.

Mrs. Webster wrote Thursday’s Brain Bit on the board, forming each letter with such precision and concentration she seemed to be in a trance. The children, in turn, pressed the worn-down leads of their pencils through the lined paper they had been given, grimacing as they made the letters. When finally she had finished, Mrs. Webster backed off from the board and read the Brain Bit in its entirety.

“A pearl begins as a grain of sand inside an oyster.”

“Mrs. Webster?” Alice said.

“What, Alice?”

“Some people eat oyster sandwiches.”

“I’m sure they do, Alice,” Mrs. Webster said without excitement. When she was filling out Alice’s report card yesterday Mrs. Webster had written under Teacher’s Comments, “Still tries to dominate conversation.”

Alice was a tall girl with a rather pouty face who was wearing what looked like a wedding dress. Its hem was frayed and grimy, but it still imparted a distinction she clearly coveted. She was the only one in the class who had her own desk—there was no room for her at the four worktables around which the other children sat in clusters—and lately she had been using it as a lectern to deliver terse little homilies about Judy Garland, of whom Alice believed she was the reincarnation.

Before Alice could launch into a polemic about oysters, Mrs. Webster hurriedly changed the subject and reviewed the week’s previous Brain Bits about the boiling point of water and the laziness of the sloth. By then it was time for reading.

The class was divided into three reading groups that Mrs. Webster taught one at a time on a large rug by the bookshelf. While she was busy with one group the rest of the children were expected to occupy themselves with various ongoing assignments; copying sentences in their writing workbook, or drawing a picture of a snake, or writing ten sentences each with “a word for a person or an animal” and “a word for what we do or what we did—a verb.”

The first group Mrs. Webster took over to the rug was the most advanced. They were on third-grade level, reading from a book titled Air Pudding and Wind Sauce. The group included Susie, a Taiwanese girl who had been in the United States less than two years and who had already, through simple industriousness, exhausted everything the second grade had to offer her. “A joy to teach,” Mrs. Webster had written under Teacher’s Comments. She had written the same thing on Kelly’s report card, but Kelly’s intelligence was an indolent, free-floating thing, a product of good breeding. Nevertheless the two girls were good friends: next year they would skip the third grade together. Their nearest intellectual rival was Eduardo, a pale, courtly boy governed by some mysterious internal ethic that kept him as composed and impassive as a samurai.

The Air Pudding group was reading aloud a story about Earl and his magic sneakers. Mrs. Webster would call on another member of the group every few paragraphs. Most of them read eagerly, fluently, their pace accelerating as they approached the end of each sentence. Occasionally Mrs. Webster would look down at her teacher’s manual and ask a question.

“Remember what Earl’s mother said that morning? Michael?”

“That you have to make your own luck.”

“And what do you suppose she meant by that?”

“That the magic sneakers won’t make your luck but that you have to make it yourself.”

While she conducted Air Pudding the rest of the class carried on with reasonable decorum. They did not need permission to go to the restroom or the water fountain, to sharpen their pencils, to talk to one another at a minimal level. These were, perhaps, token concessions, but to me they seemed revolutionary. I remembered my own school days, forty children sitting erect at their desks, praying they could last until recess without wetting their pants, desperate to speak, to move, to learn in the way their instincts told them it was done.

At Thorndale these rights were partially restored, and no one seemed to suffer for it. Mrs. Webster monitored the class at large with some part of her attention, and whenever the volume or the movement reached an intolerable level she turned around in mock disbelief.

“My goodness, people! Is this my class? Have I wandered into the wrong class by mistake?”

In correcting her class Mrs. Webster was neither peevish nor intimidating. Her overall demeanor suggested a reasonable person who was shut up every day with 22 second-graders and determined to make the most of the situation. Perhaps because she had begun her career later than most (she had waited until her own children were grown), her teaching skills seemed based more on instinct than on formulated precepts. Some of the younger teachers I had seen—those whose professional vocabulary seemed to consist entirely of positive-reinforcement slogans—treated students with chilling reserve. They were clinicians, tolerant and impassive. Mrs. Webster’s gifts as a teacher centered around her ability to project herself to the class as a human being. She did not excite them, and surely she had her failings, but the children recognized in her something kindred and authentic, and they were comforted by her presence.

There were 25 teachers at Thorndale, all of them women. “I’d say Mrs. Webster is one of the five or six who are any good at all,” a staff member told me. “Most of them are incompetent. A few of them are downright sadistic. They’ll tell their kids all day how rotten and stupid they are, then try to fail them just out of spite. Year after year they hand in the same old lesson plans. At twelve o’clock you can bet they’ve got their purses up on their desks ready to go—they’re just coasting through the next two and a half hours.”

I did not know which of the teachers at Thorndale were “good” and which were “bad.” I would see them in the teachers’ lounge, eating leftover tuna casserole from plastic containers and talking about cat diseases and recreational vehicles and planned communities where they were thinking of buying. Occasionally they would express concern about some recalcitrant fourth-grader they were scheduled to have in their class next year. They seemed to take their teaching duties no more or less seriously than the world at large took them as teachers. Some of them were incompetent, no doubt, and no wonder.

It is one of the great ironies of American culture that the transmission of knowledge to children is regarded as more of a hobby than a profession, a task that should be carried out all but voluntarily by an inexhaustible supply of prim but good-hearted matrons and distracted young women marking time until they find husbands. In our society an elementary school teacher remains a marginal figure, a pleasant nonentity like the woman who comes to the door collecting for the March of Dimes.

The image is persistent, and because we have such a peculiar resistance to the idea that the teaching of children is a serious calling, those who undertake it are routinely patronized and abused. At Thorndale, for instance, the staff had on the average twenty minutes for lunch, which they ate in a teachers’ lounge they had furnished themselves by raising money from bake sales and raffles. They were plagued by meaningless paperwork, and if they wanted something for their children other than the minimal classroom materials—construction paper, glue, clay—that the school provided, they had to buy it themselves. In some schools teachers are required to perform “spoon duty,” which means they have to stand guard in the cafeteria during breakfast, checking each student’s cereal bowl to make sure he does not leave his spoon in it.

The school finance bill passed during the special legislative session in July sets the beginning salary for a teacher in Texas at $8460 a year. After seventeen years he or she (most likely she) can expect a salary increase to a ceiling of $13,818. It is a livable but grudging wage, hardly commensurate with what is arguably the most crucial job in society. Teachers, of course, have the summer off, but many of them—those for whom their teaching income is not merely supplemental but the basic support of a family—spend those three months working at another job, and frequently moonlight during the academic year as well.

One of the basic misconceptions about teachers is that they keep the same hours as their students, that they leave school at 2:30 in the afternoon and are settling down to The Edge of Night at the same time their kids are tuning in Cartoon Corner. Not so. More likely they leave school at 4 or 4:30, hauling home unfinished lesson plans, ungraded papers, unformulated projects they must complete on their own time.

Considering the tension and low pay and utter lack of status an elementary school teacher must endure, it’s not surprising that the position attracts those whose commitment to education is often minimal or temporary. A majority of elementary school teachers leave after five years or so. The aggressive, career-minded teachers who have lately been flooding forth from the universities naturally gravitate toward positions of greater responsibility and higher pay. The system tends to channel the most ambitious and committed teachers away from the front lines, and leaves in their place the same sorts of teachers who have always been there.

I don’t want to imply that many of these teachers are not gifted or dedicated, only that the system does not encourage these qualities in those whose contact with the students is most direct and prolonged.

The system certainly does not encourage men. In Texas there are ten times as many women teaching in elementary schools as men, though male principals outnumber female principals four to one. Granted, there is something suspicious about male grade school teachers—many think of them as being rather giggly and manic, incessantly babbling to their students about the glories of nature and so forth—but that stereotype is ripe for revision. It will be revised only when men perceive classroom teaching as a respectable vocation, and of course they will only see it as such when it is endowed with a respectable salary.

While Mrs. Webster worked with the Air Pudding group I helped Drew with his reading. Drew was a short kid with sharp, narrow features and a utilitarian haircut that suggested he was regarded in his home less as a human being than as another object, like a toaster or lawn mower, to be maintained. Every day he wore the same faded Big Bird T-shirt. He seemed to sense that in certain fundamental ways he had been deprived, and this knowledge outraged him. He sat there fuming at the book he was reading to me. Every word was a malevolent force, and he spat them out one by one, with no real sense of how they fit together.

“Watch . . . me . . . climb,” he read, “watch . . . me … climb . . . I . . . am . . . Cubby . . . Bear . . .”

Drew’s problem, according to Mrs. Webster, was that he had a “low self-concept.” So did Janie, who walked around the classroom blithely announcing that she was fat and stupid, and that nothing could be done about it. So did Theresa, whose mother dressed her as she dressed herself, in garish polyester clothes that didn’t fit. Theresa always carried a purse dangling from the crook of her arm and whenever someone regarded her with ambivalence she would break into tears.

The three of them were among the members of the lowest reading group. They read at “pre-primer” levels from books filled with simple rhymes and colorful pictures and much white space. They spent a good deal of time each day with the resource teacher, whose job it was to deal with children who were having learning or emotional difficulties, or with the Title I reading teacher, who was there to help the kids who were not “on level.”

Both these women were headquartered in the same classroom, which was down the hall from Mrs. Webster’s room. They were both young, hip, unflappable. They were responsible primarily not to the principal of the school but to a roving district supervisor, and so some of the teachers at Thorrnale viewed them as elitists, an impression they fostered by eating their bean sprout and avocado sandwiches in their classroom rather than in the teachers’ lounge like everyone else.

But their classroom was, after all, a very congenial place. A child who entered it was bombarded with stimulation: books, tapes, and reading games spilled out of every available shelf, and the teachers themselves had stocked the classroom with posters, gerbils, plants, parakeets, even a portable oven the kids used to toast bread on which to spread their homemade plum jelly. The room was subdivided into five or six different areas, each of which had some cozy feature—a couch, a cubbyhole, a womblike place to read.

The place made sense, not because of the gadgetry that was available but because of a certain mood that the room cultured. Learning was not just tolerated here, it was sought out. The room engaged the children, met them on terms they did not yet have the awareness to demand on their own.

The two special teachers were shrewd and patient. Since each had only five or six students at a time they were able to provide enough individual attention so that even the most obstreperous of them remained calm and industrious.

This sort of learning environment had not existed when I was in school. Children with behavior problems were sent to the principal or merely slapped around; those who were slow were jettisoned when the time came for the class to move upward to the next grade. There were no real provisions for children whose performance kept them out of the mainstream, and I thought it ironic that the resource rooms and support teachers that had been called into being to aid problem children were now the most effective learning centers in the schools.

Their success is due, of course, to money, to the establishment of what is essentially a leisure class of teachers who don’t have to face a daily battle for supremacy with twenty or so children. It is an expensive luxury, but if American public education is to continue its glacial progress toward the humane enlightenment of its charges, that luxury will have to be viewed sooner or later as a necessity, as a simple childhood right.

For now, though, the “normal” kids were out. For those who had no special way of calling attention to themselves the rhythm of classroom life remained unbroken, uneventful. The day was divided into little compartments—reading, spelling, lunch, math, social studies—through which the students were expected to pass with as little fuss as possible, making sure, as they left each compartment, to pick up after themselves. Their reward for doing this was being allowed to leave at the end of the day.

Over the weeks I came to admire the children’s endurance, to feel that their tolerance of the educational system that had closed in on their lives was almost saintly.

They were, of course, children, and these were lofty adult qualities I was overlaying on their perceptions. Still, at lunch, when the woman serving the food would see me in line, motion for me to cut in at the front, and then offer me a selection of food that the children did not have, I wondered how they could not sense the profound inequities they were enduring. Over the years the educational system had made efforts to appease them, to make their incarceration sunnier, but it had not yet been successful at understanding them; and so almost every natural way in which they were made to perceive the world—touch, talk, movement—was still regulated, seized in its entirety and rationed back to them a piece at a time. But their trust remained. It remained total, because that was all they had. They believed in their education, though they did not know what it was that imposed it upon them, or why.

How well Texas is doing by its schoolchildren is an unresolved matter. There are no objective standards for ranking a particular state on the quality of its education, but various indices exist that suggest Texas is slightly worse than the national average. National Education Association figures compiled for 1976 show it to be twenty-fourth in money spent for teacher salaries, thirty-seventh in expenditures per student (though third in the number of students in average daily attendance). The National Association for Education Progress, which divides the country into four regions based on an assessment of their educational product, assigns Texas to the region that is ranked third.

Nevertheless, when we speak about the educational commitment in Texas we are speaking in terms of billions of dollars, about 2.5 of them this year. Three-fourths of that money, if not more, will go to pay the salaries of teachers, administrators, supervisors, bureaucrats. The rest will be spent on maintenance and operation, transportation, special education, bilingual education, equalization aid, and a dozen other projects.

The money is distributed according to the provisions of the Foundation School Program, which requires basically that each district, in order to receive state education funds, must come up with what is called a Local Fund Assignment, a percentage of the educational bill that the state assigns to the district based on the market or agricultural value of the district’s taxable property.

By the time this $2.5 billion reaches the schools so much has been waylaid and parceled out that Thorndale, say, is fortunate to have $500 beyond its basic operating budget to distribute among its teachers for the purchase of extra classroom materials. Billions are pared down to hundreds and finally to tens and ones. A teacher at Thorndale decides to take her students on a field trip to an ice cream factory and pays each of their 15¢ bus fares herself. A reasonably conscientious teacher can count on spending $200 a year out of her own salary on such excursions and projects, and ultimately her willingness to spend that money, because in some way it is worth it to her, has an impact on learning that $2.5 billion of assessed and appropriated funds cannot match. The system can produce electronic learning devices and talking textbooks, it can produce uncountable stacks of printouts filled with vital data, it can produce insipid educational films in which third-rate mimes lead black, white, Mexican American, and native American children through the Wonderful World of Concepts, but it cannot produce education. That is something only a teacher can do.

In the wide world, school finance and other great educational issues were furiously debated, but these were storms that blew themselves out before they ever reached Thorndale. Somewhere unimaginable amounts of money were being spent, in thousands of minds and computers the concept of education was being reformed, but Thorndale remained curiously unaffected. A second-grade student at Thorndale, picking up during Silent Sustained Reading a book with thirteen pages on each of which an animal said merely “I can jump!” could not know that this book was the product of two authors, not to mention an illustrator. He could not know that the attitude test he was being given while his teacher was looking over his shoulder (sample question: “How do you like your teacher?”) was the result of profound study and considerable expense.

At Thorndale you could forget the billions of dollars that somebody was spending somewhere; you could forget pilot projects and government-sponsored development labs and task forces and computers disgorging reams of demographic data that nobody ever read. You could forget Jean Piaget and A. S. Neill and Jonathan Kozol and Charles E. Silberman. The true force in modern education was the Happy Face. It was everywhere, it was self-propagating. Someone would decide that students needed a test asking them “How Do You Feel Today?” The students would be given a row of faces—the Happy Face and its variants the Sad Face, the Glum Face, the Mildly Amused Face—from which to choose. There were calculator-like machines called Digitors, on which a kid selected a mathematical function and then punched out the answer to an equation the machine provided. If he had the right answer, a green Happy Face appeared on the screen; if he was wrong a Sad Face came on in red with a frown that seemed excessively sour. Happy Faces were in the halls, on the mimeographed permission slips children took home to their parents to sign, on the covers of educational brochures and on the pages of workbooks. The Happy Face served the illusion that education was always fun and evenhanded, that its failures were not immutable. Surely for every child who conceived of God as an old man with a beard there was another who saw him as a bright yellow schematic smile.

During the last week of school the day-to-day rhythm began to dissipate. A string quartet appeared one afternoon in the cafeteria, played a selection by a “Mr. Mozart,” and enlisted a few students for a summer music workshop. The fifth grade put on a play called “The Three Sillies” in which a boy was kissed by two girls, causing a great uproar in the audience. (“Mrs. Webster, did those girls really kiss that boy?” “Well, I don’t know, Ruth, but would it be a crime if they did?”) There was a daylong track meet, and almost daily viewings of The Electric Company, during which Mrs. Webster tried to catch up on her paperwork. Occasionally the fifth-graders would deliver the school news over closed-circuit TV, an amenity Thorndale had managed to purchase with revenue from several PTA carnivals.

“Now the unit news. Most of the roadrunners and pilots are working on Mother’s Day gifts. Mrs. Barnett’s kindergarten class isn’t, they’re studying solids and gases. Now here’s David with a report on extinct animals.”

“Hello, this is David with a report on extinct animals. The buffalo, as you have all heard of, have been hunted down for a hundred years. Pandas, which many of you do not see very much anymore, is now extinct…”

The school newspaper came out with its monthly issue, featuring heavy coverage of the Mother’s Day gifts. (“Dear Editor,” a student wrote in, “I would like to comment on the work being done in the cafeteria. Sincerely, Linda M.”)

In the afternoons, while the second-graders worked on their own Mother’s Day gifts, Mrs. Webster would sometimes play music, the soundtrack from Winnie the Pooh and the Blustery Day, or a retrospective of Beatles songs sung by the Chipmunks. Once or twice the class had Show and Tell.

“This is a bedbug,” Alice said, holding up a fuzzy stuffed arthropod on an elastic string. “It says, ‘I’m a Bedbug.’ And if you sleep with it, it’ll bite you and you’ll die the next morning.”

But even in the last week of school the curriculum was not abandoned entirely. Each afternoon the three teachers who composed Mrs. Webster’s unit divided their students among themselves for math, so that children who worked on the same level were in the same class. Unfortunately for Mrs. Webster this system brought Richard, the second grade’s resident firebrand, into her room. Richard was not moved by the mores of Thorndale: he would not sit in his seat, he abused the other kids, he made animal sounds while the teacher spoke. At home he was largely ignored by his parents, and at school he lived his life with a simple integrity that in some ways was admirable but in most ways was tiresome. He spent a good part of each day sitting by himself out in the hallway, where he did not seem particularly discontent. Earlier in the year he had signed a “contract”—cosigned by the principal and his parents—in which he agreed to three provisions of conduct: he would show respect for his teachers, he would not pick fights with his fellow students, and he would pay a reasonable amount of attention to his own education. On the frequent occasions when Richard violated all three terms of this contract he was taken to the principal’s office where, with much ceremony, in the presence of a witness, he was whacked with a short, stout board.

He remained incorrigible, and Mrs. Webster watched him with one eye while she taught a multiplication lesson involving imaginary creatures, from the math workbook. “Each Feebeegee has two hats. How many hats would two Feebeegees have?” “Each Gloopus has six legs. How many legs would ten Gloopuses have?”

Richard bounced around at his desk impersonating a Gloopus. When Mrs. Webster told him to sit down he kneeled on his chair and coiled back on his legs, ready to strike.

He was no better the next day, when the class was playing a game in which one student would postulate a. mathematical equation and another would name the function it demonstrated.

“You don’t know what you’re talking about,” Richard told one of the girls. “You’re stupid.”

“Richard, sit down and be quiet!”

But there was anarchy in the air. The class was fidgety. Half of them were paying no attention at all. When a boy guessed a wrong function Janie stood up and exclaimed, “Jesus Christ!”

“All right,” Mrs. Webster said. She passed out mimeographed sheets on which there were long columns of subtraction problems. “Now unless you calm down I’m going to keep giving you more of these math sheets until you have nothing but work to do all afternoon.”

The threat of learning was, at the moment, Mrs. Webster’s only weapon.

For a month the children had been working haphazardly on a social studies project. Each of them was to report on a particular state, and during the last week of school these reports came due. Alice was first. She stood up by the board and pointed to Oklahoma on the world map.

“The state bird is the scissor-tailed flycatcher,” she said. “The state flower is the mistletoe. The state Indian is the Redskin.”

Louise reported on Michigan. It was nicknamed the Wolverine State because of all the wolverines there. In Michigan there was a five-mile-long suspension bridge across the Mackinac Straits. The capital of the state was Lansing and not Detroit.

“These are interesting facts,” she said.

The rest of the class wrote the interesting facts down in little homemade notebooks Mrs. Webster had stapled together for them. For some reason they seemed fascinated with states.

“Slow down!” they called out when someone spoke too fast for them to get the facts down on paper.

“The population of Hawaii is 769,913,” Janie said. “The state flower is the hiccupus.”

“Hibiscus.”

“Hibiscus. And the state bird is the nene and it means the Hawaii goose.”

When Janie sat down after this meager recitation the class was outraged. They wanted more information.

“She didn’t even tell us the capital!”

Mrs. Webster calmed them by picking up an encyclopedia and reading from it.

“Hawaii consists of one hundred and thirty-two islands stretching over fifteen hundred miles.”

“Mrs. Webster,” Susie asked, “is Hawaii part of America?”

“Yes, but it isn’t actually hooked on.” “Then how come Hawaii isn’t part of Africa? How do they know what shape America is?”

Mrs. Webster was torn. She wanted to answer these questions, to indulge Susie’s curiosity, but something pulled at her, the need to move on, to cover territory, to play out the lesson plan. There was no time, too many children were counting on her for direction for her to run off in pursuit of abstract concepts. She needed to bring Susie back to solid ground: the capital of Florida is Tallahassee, Iowa is known as the Hawkeye State.

“Well, Susie, I don’t actually know why it’s part of America and not part of Africa or someplace. You’d have to ask someone who lived a long time ago.”

“But they’d be dead!”

“Well, you’re right. But we really don’t have time to talk about it right now. You’ll learn about all this later.”

After school Mrs. Webster and the other teachers in her unit sat in the children’s chairs rummaging through a great pile of manila folders they had spread out on the tabletop. They were updating the students’ personal folders, each of which was about half an inch thick, containing dozens of forms calling for “Enrollment Data,” “Special Services Data,” “Health Data,” for assessments of the student’s progress in his or her “Cluster of Skills” or “Reading Ladder.”

“Demonstrates an understanding of and uses consonant digraphs.” Check.

“Combines phonetic and textual clues.” Check.

“Instructions: At the end of each school year the pink carbon copy of the Written Report should be filed in this envelope. Remove the Personal Development section before filing. Copies are cumulative and should be kept in consecutive order with the most recent report on top.”

“Instructions: Update Reading Cards. Update Math Profile. Update Vision Screening Results. Update Hearing Screening Results. Update Listing of Siblings.”

“Instructions: Clean folders of other clutter.”

School ended on a Tuesday. During that day no one at Thorndale deceived themselves into believing they were teaching or learning anything. The whole school was marking time. Every film projector was in use, the popcorn machine was sputtering away in the hall, all the fifth-grade boys had come to school dressed like the Fonz, and their teachers—in the same hysterical mood—were wearing ponytails and bobby socks.

During lunch the teachers sat in the lounge trying to decide if the cut-glass bowls one of them had seen at Edison’s would make suitable end-of-the-year gifts for the aides. When they had agreed on the bowls they went on to conclude the arrangements for the annual teacher party to be held at a local steak-and-salad-bar restaurant. It was at that party that the Secret Pals would be revealed.

The Secret Pal concept was this: in order to boost morale, each teacher was expected at some point during the school year to present a gift on the sly to a colleague whose name she had drawn. The recipient would not, of course, know who her Secret Pal was, and would not have an opportunity to thank her in person until the party at the end of the year. But in the meantime she could express her thanks in writing on the big Happy Face poster put up in the lounge for that purpose. “Whoever you are, the memo set is lovely!”

In Mrs. Webster’s room on the last day of school the kids were cleaning off their desks, playing Simon Says, Quizmo, Consonant Bingo. Mrs. Webster cleared out her desk drawer, passing out old Easter candy and stickers with pictures of historical events. She gave back the toys she had taken up from her students during the course of the year—a plastic cow, some play money, a Donald Duck motorcycle.

The afternoon passed at its own excruciating pace. The kids were gathering together the artwork they had done during the year. I walked around and looked at it. Butterflies, houses with a thin streamer of blue sky at the top of the page, sharks, flowers. When I looked down over Drew’s shoulder I saw that the watercolor he was about to wad up and stuff into his notebook had none of these elements. It was an eerie desert landscape in the aftermath of some fabulous intergalactic battle. Recumbent furry shapes littered the ground. Standing above them were beings of light.

“I think that’s really good,” I told him. “What’s the name of it?”

Drew scowled and looked away. “The Terror of Everything,” he said.

Mrs. Webster was still at it, handing out bowling passes someone had given her, and balloons, and stale Tootsie Rolls.

“I’m going to give everybody some pretzels if you’ll promise me that you’ll try very hard to read a lot this summer.”

Everybody promised.

Finally at 2:25 Mrs. Webster stood at the door with the report cards in her hands.

“Every year,” she said, “I have a good class, but I think you’re the best class I’ve ever had. And I love every one of you and I’m going to miss every one of you.

“Now I want to tell you that report cards aren’t all that important. I don’t like report cards. So don’t worry about them, don’t compare them because that’s not what they’re for. Some girls and boys learn a lot faster than others. That doesn’t mean the others aren’t as smart. It just means they don’t have their minds on their work as much. An N doesn’t mean you’re failing. It just means you have to improve.”

But the kids knew better. Maybe they did not know precisely what N stood for—Not Satisfactory—but they knew what it meant. They had come to school to learn how to deal with school, and N meant that they had not succeeded, that they had not understood what it was that Thorndale wanted from them, why it cajoled them, harassed them, pursued them so relentlessly. Some of them would live out a long, plaintive childhood, never knowing.

Something serious was going on here, but on the far side of Mrs. Webster there was the beach, TV, Six Flags. They would grab their report cards, hug their teacher, and walk out of bondage into the radiant summer afternoon. That was a concept they could understand.

- More About:

- Longreads