This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

There is an area on my family’s ranch in the Hill Country that has captivated me since childhood. It is a valley flanked on one side by a steep, densely wooded limestone embankment and on another by a creek that runs for miles. Oaks and junipers crowd together throughout the valley, fracturing the sunlight so that even at the peak of day the area is cast in a mottled luster. Beneath the trees, the terrain is covered with small rocks, while the soil itself looks nothing like the caliche or chalky dirt seen elsewhere on the ranch; rather, it is a rich chocolate, almost black, and when you grab a handful of it and let it crumble through your fingers, you can almost feel the minerals that have nourished this land for centuries.

The valley is a place for walking alone, or with someone very close. I’ve done it since I was a small boy. To this day I carry memories of early walks with my older brother, who is now dead—memories suspended in broken light, like the valley itself, of the two of us, strolling and talking about girls, chasing armadillos, gasping at the sudden blur of deer in flight, or just passing through with our fishing poles in hand, listening to the crunch of leaves beneath our tennis shoes and stooping, now and again, to pick up a smooth dark rock that might, through a boy’s eyes, resemble an arrowhead.

We had always known that Indians once lived on the land that we later came to own. Who they were, when they arrived, what they did there, and why they left were matters of impenetrable mystery, but their flintwork was evident throughout the acreage. Only occasionally did one of us discover a true arrowhead, but still it thrilled me every time I found any shard of flint that seemed to have been handled by an Indian. One summer I announced to my mother that I wanted to gather enough flintstone to build a rock garden. I don’t know what I had in mind really, but my grandfather overheard and offered to help me. We hopped in his jeep, and he drove me to the valley. While we crouched together beneath the trees and tossed rocks into a bag, he informed me that we were standing on the very spot where Indian objects were buried.

My heart must have pounded. What kinds of objects, I wanted to know. Who knows, my grandfather said. Arrowheads. Maybe clothing. Maybe bodies. He smiled, and I swam in a delirium of fantasy. A question sprang to my mind and was halfway out of my lips when my grandfather answered it: “But we shouldn’t dig it up. It’s better just to let it stay the way it is.”

It was my grandfather’s habit to indulge my every wish, so his words took me aback. Something was at work here, an ethic that took me a moment, but only a moment, to comprehend. When I did, I as a boy felt suddenly wise, and hopelessly in love with the valley and all its ancient mysteries.

One afternoon this past summer, I arrived at the valley and gazed in astonishment. Huge holes four feet deep had been dug throughout the area; mounds of dirt were heaped everywhere. It was as if dozens of long-buried bombs had suddenly erupted. Looking down into the holes, I could see that the roots of the oaks that towered over me had been slashed; the trees would soon be dead. Flint was strewn everywhere, along with objects that had not been here before: a torn gardening glove, three or four beer cans, broken lantern glass, two rusty shovels, and a Crown Royal whiskey pouch. Inside the pouch were four long spear points. They were the finest I had ever seen on the ranch. But today I stood in the middle of this valley—once sacred, now in a permanent state of torture—and I knew that the beautiful rocks I held in my hand represented, to whomever had done this damage, an ethic precisely counter to the one that had governed this property for so long. The rocks felt cold in my hand, like money, and I must confess that my blood has been running cold ever since.

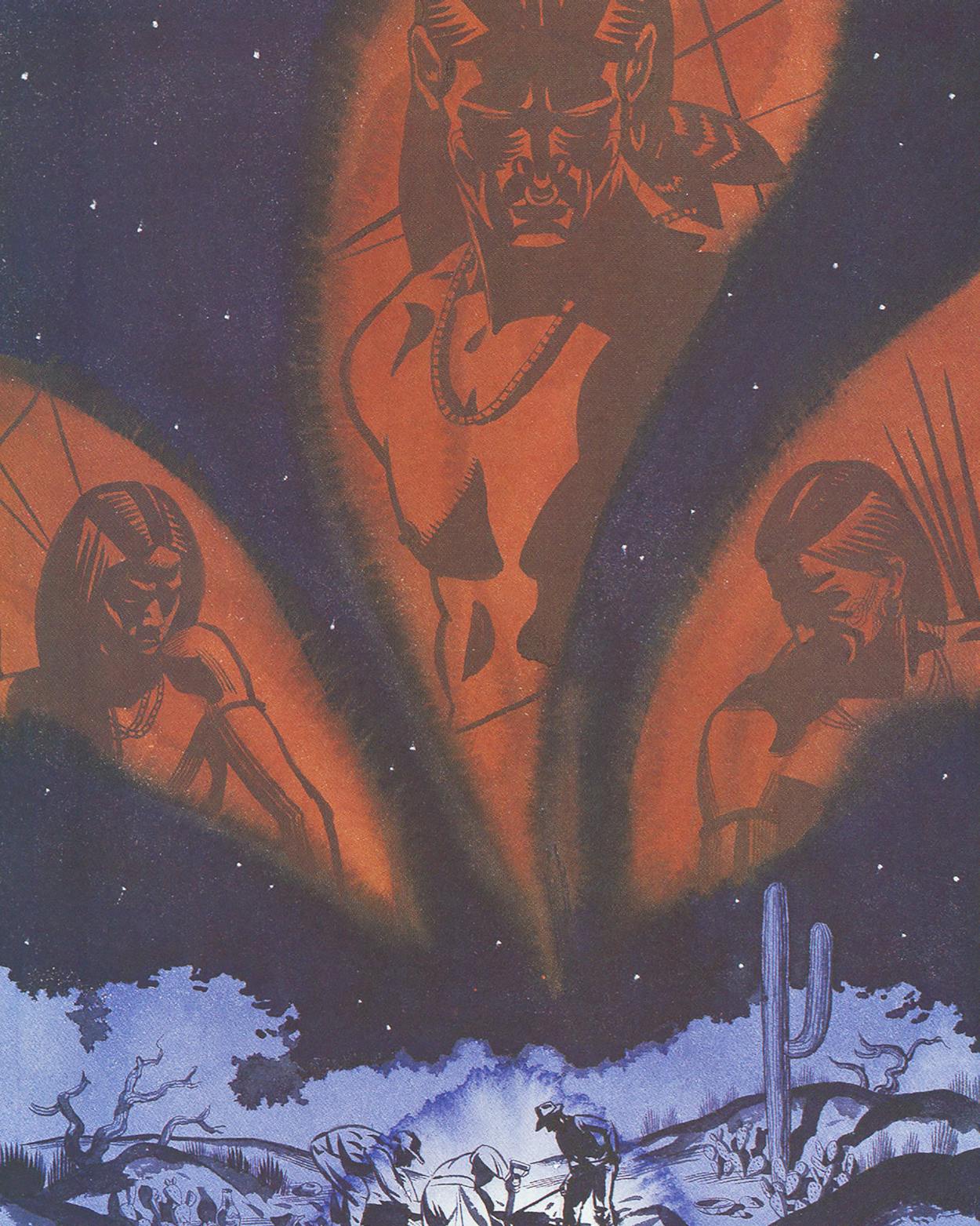

The written history of Texas is about four hundred years old. The remaining 98 percent of our state’s history lies beneath the soil, and, chunk by chunk, it is being stolen from us by a breed that desires this history only for what it will bring in cash. Archaeologists call the offenders pothunters. The persons in question—and there are thousands of them, ranging from weekenders to hard-core professionals—prefer to be known as collectors. Virtually all of them insist that they never dig beneath the surface, or that when they do, it is always with the landowner’s permission and clear understanding of what is being done. One does not have to look far or talk to that many people to learn just how false these claims are. In northeast Texas, an area once populated by the Caddo Indians, grave robbers plunder unmarked cemeteries, smashing through skulls in search of ancient burial goods. Farther south, in the Nacogdoches area, they troll along rivers and lakes, fouling the waters as they probe for artifacts with long vacuum hoses. In the lower Pecos region of West Texas, they cut out pictographs that have adorned limestone rock shelters for centuries and leave parklands looking like war zones after digging for painted pebbles. And throughout Central Texas, where the sheer variety of Indian flintwork is unrivaled anywhere in the nation, looters use bulldozers to destroy subterranean campsites for the sake of a handful of arrowheads. The end result is that nearly all of our state’s prehistoric repositories have been hopelessly devastated by a largely unnoticed criminal class. Our state is being robbed blind, and the robbers have no intention of stopping.

Texas did not invent pothunting, but its practitioners thrive here like nowhere else in America. In a state where more than 90 percent of the land is privately held—and indeed where the sanctity of private property is embedded in our ethos—the protection of Texas’ ancient history falls not to the government but to the landowner. It is the will of the Texan that he patrol his own acreage, that the lawmakers leave him free to do with his land whatever he pleases. Looters could not ask for a more accommodating atmosphere. They have eluded and outfoxed the Texas landowner, oftentimes without having to resort to trespassing. In these cases, they have cleverly exploited his independent streak, conning him with promises of treasures to be shared, playing on his distrust of state officials and his ignorance of history. It is our ignorance that is most humbling, for Texans define themselves by their allegiance to the land of the state—not to property deeds and survey sticks, but to the blood of the soil and all the dreams that lie underfoot. When the land is plundered, we are set adrift, and we become something less than Texan.

On a scale of one to ten, I would’ve rated your site an eight and a half,” said Jeff Merkord as we stood over what was left of the mounds on my family’s ranch. Merkord smiled somberly; he had been staring down at looted mounds such as these for as long as he could remember. People he has known all his life are pothunters, and for a period of time, so was he. But Merkord, a slow-drawling, scruffy-haired handyman in his early thirties, fell under the spell of the 11,000 years of culture he was plundering. The previous inhabitants were migrants from the north, or in some cases from northern Mexico. They arrived in small bands of extended families. Together they sought out buffalo, staking out a dozen or so miles of territory through which they would shift their campground according to need: to one area when the pecans were ripe, to another when the white-tailed deer were beginning to congregate. They knew how to manipulate the land—burning off prairies to attract bison, for example—but saw what hailstorms did to their fruit trees and so eschewed farming. They were hunters and gatherers who neither lived for bloodshed nor avoided it. Beyond this, there is little known about the prehistoric Indians, not even the names of their tribes. Yet interwoven with the mystery of the people were other riddles: why and when climates changed, the shaping of the land, the sudden appearance of javelinas in the seventeenth century, and the disappearance of antelope at the beginning of the twentieth.

The more Merkord pored through the questions of the past—the more he appreciated a site for what it told rather than what it contained—the queasier he felt about pothunting. While doing odd jobs for Hill Country ranchers, he would come upon a secluded Indian mound and sit there for a while, contemplating the rituals performed on that very spot a thousand years ago; a week later he would return to find it gutted by looters who happened to be friends of his. Eventually, Merkord replaced his shovel with a notepad. He now spends his free time recording sites and submitting them to the confidential files of the Texas Archaeological Society. The looters in the area don’t talk to him much anymore.

Still, Merkord has lived in Wimberley long enough to know where to find conversation, and at one such gathering he heard from looters about the plundering at our ranch. According to rumor, a small group dug on successive nights and eventually made off with numerous spear points, a conch shell bead that was part of a breastplate, and—the major find—a corner tang knife used for skinning that possessed some vague ceremonial significance, one which, depending upon its length, could sell for several hundred dollars.

What disturbed Merkord most was what the looters left in their wake. Scattered about the valley were the fragmented bones of bison dating back perhaps 3,500 years. “It’s rare to find those kinds of bones around these parts,” he told me and gestured into a nearby pit. “See, what you’ve got here is a series of middens—one ancient trash pile on top of the next, each one older than the one on top of it. Depending upon how deep these bones were buried, we could more or less figure out when the prehistoric buffalo returned to this area. And, of course, that would tell us something about what was going on in the environment here that made the bison want to return. The positioning of the bones would tell us what they were used for or how they got there in the first place. And that would tell us something about the habits of the people who lived here. But now there’s no way to know.”

Merkord shook his head. “These guys know how to find arrowheads and dig ’em up,” he said as he combed the ruptured soil with a hoe. “But they don’t know what they’re doing to history.”

We spent that morning driving through the hills, and through Merkord’s eyes I began to see the country as an archaeologist—or a looter—would. We searched for muhly grass that grew out of seeps and for evidence of springs that had not seen running water in a thousand years. Invariably we came across fist-size limestone rocks, cracked by an ancient fire. Beneath the rocks was a mound of cultural debris: flint chips on the surface and soil nourished by animal remains. Merkord shuffled here and there as if hypnotized or lost. His eyes squinted as he exercised his imagination. Was this a campground, and was the crest of a nearby slope a lookout? Some of the flint did not look local; was this a sign of trading or traveling? I watched my guide with what began as amusement and slowly grew into awe. As he sifted through dirt and ran his fingers along limestone crevices, I suspected that somewhere along the way Jeff Merkord had discarded as utterly irrelevant the fact that he bore no blood kinship to the land’s earlier inhabitants. He had seized upon a connection of a different kind. How they had fared here seemed, in some indistinct way, absolutely crucial to him. Whatever the source of Merkord’s empathy, I found it immensely moving. When I said good-bye to Merkord that afternoon, I thanked him and said that he was welcome on our property anytime.

Thereafter, I set out on my own to explore the middens of Texas, only to find myself gazing at ruptured remains. Places I didn’t know existed in my resident city of Austin had long since been discovered as promising sites and had been pocked with deep holes. Along riverbanks and beside creekbeds, in state parks and on undeveloped commercial property, I found evidence of the pothunters’ furious digging, like rats chewing through drywall in their mindless quest for some coveted morsel. Their methods are those of a species that will not be denied. In the Hill Country, trespassers have cut barbed-wire fences so that the cattle will escape the property and allow them to burrow undisturbed. In a creek south of Austin, a looter dug until he managed to tap a landowner’s water supply and drench a nearby site until the arrowheads surfaced from the muck. Farther south, in Calhoun County, along the Victoria barge canal, a looter perfected the method of backing his tugboat up to the shoreline at full throttle, causing heavy waves and massive erosion until nothing was left of the banks except the artifacts beneath them.

North of Paris, on a vast stretch of land abutting the Red River, I listened to a 77-year-old man named Arnold Roitsch talk about his experience with looters. Between the river and where we stood stretched the mulchy expanse of what had been, until three hundred years ago, a Caddo Indian village. Roitsch bought the property in 1986 and had no idea that he had purchased one of the state’s greatest pothunter magnets. “They’d come out here at night, sometimes by boat over from Oklahoma, carrying portable generators to keep the lights going, and they’d put a canvas shield around them so they couldn’t be seen from the road,” he said. “I’d come out quietly, and I’d see them sticking these long stainless steel rods into the ground, poking around. And I knew what they were poking around for, because there’d be these ceramic pots sitting at the edge of the hole where they were digging. When I asked them who gave them permission to do this, they’d say, ‘But we’ve always dug here. No one’s ever minded before.’ I’d chase them off, but they always came back, and they left bones scattered everywhere they dug.”

One day Roitsch was paid a visit by a well-known Texarkana pothunter. The man offered to purchase the twenty-acre mulchy area from Roitsch, bulldoze it, and then return the property to the landowner when he was finished. This didn’t sit well with Roitsch, who told me, “I’m a little funny, I guess, but I hope seven hundred years from now someone won’t scatter my bones all over the land. The good Lord put the Indian here for a reason, and I think that his bones should be respected.” When the pothunter heard these sentiments from Roitsch, he vowed to leave all bones intact and to give the landowner half of all that he found. Otherwise, warned the pothunter darkly, the nighttime digging would continue.

Eventually, Roitsch chased the pothunter off his property, then the night diggers returned. These days, he told me, “I don’t chase off nearly as many people as I used to. I guess word’s gotten around that there’s nothing here worth digging up anymore.” He sounded relieved.

In the office of the state archaeologist in downtown Austin, two file cabinets bulge with memos, reports, and clippings. These are the state’s archaeological vandalism files. Leafing through the folders, one can quickly discern a portrait of the pothunter. Some are driven by money, by the $20,000 to $100,000 a year they can make selling Indian artifacts to wealthy collectors, museums, and each other. Many exhibit their wares at gun and knife shows, advertise in newspapers, or communicate through long-established back channels to avoid taxation. Some, often affluent professionals, prefer to hoard their treasures. Others are more difficult to categorize, except that pothunting seems to be their only calling in life. Speaking of a veteran pothunter who is currently doing time for an unrelated offense, an East Texas archaeologist told me, “The guy has an indisputably low IQ. But when it comes to finding Indian sites, he is truly a genius.”

What unites them is a craving for artifacts and, undoubtedly, for the thrill of hitting pay dirt. Archaeologists and current and former pothunters alike speak of the practice as being addictive. Like all addicts, pothunters go to sociopathic extremes to attain their end, studiously ignorant of the havoc they generate. And as with any other addict, pothunters show great indignation when forced to defend their practice. Archaeologists, they say, are the true villains, intent on burying all the artifacts in university basements, where only their academic buddies can see them. There are plenty of pots and arrowheads to be had by all; none will be missed. What we do, say pothunters, is no different from other great American pastimes: hunting, fishing, coin collecting. So let us collect!

Their rationales test the imagination. What would respectable hunters think of a man who burns down whole forests to smoke out his prey? Could a person who poisons a lake to coax his trophy to the surface be called a fisherman? And would a jury be swayed by a bank robber’s insistence that he was merely engaged in the act of coin collecting? Because pothunters are addicts and not merely thieves, there is no honor among them. Looters are loath to discuss the sites of their conquests with comrades for fear of a double cross. They delight in shadowing the activities of the respectable archaeologist and plundering his discovery the moment he has quit for the day. And the market is flooded with fraudulent artifacts: fake pottery, fake Folsom and Clovis points, fake corner tangs. A wealthy collector sued one of the state’s most prominent pothunters after the latter sold the former thousands of dollars worth of phony vessels and stone tools.

Pothunters often profess a fascination, though crude and devoid of context, with Native Americans. For some, like Jeff Merkord, that fascination can be cultivated into a reverence for the past and a desire to protect it. But even archaeologists who are on friendly terms with pothunters could not tell me of a single looter who had a serious ethical problem with grave robbing. Indian groups are outraged, naturally, and their efforts have led to the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, a federal law that mandates the return of the bones of Native Americans to certain cemeteries. But, as James Bruseth of the Texas Historical Commission told me, “So much of the Caddo Indian ancestry has been lost due to pothunting that the typical Caddo descendant doesn’t know any more about his heritage than does the typical East Texas farmer on whose property the looted cemeteries sit. ”

The vandalism files are crammed with the names of pothunters. State archaeologist Robert Mallouf knows who the worst offenders are. But Mallouf, a tall, quiet man who wears jeans and boots to the office, is always several paces behind his nemeses. The state archaeologist’s staff is the same size (seven) as it was twenty years ago, and he is painfully aware that it would be a waste of time to lobby the Legislature for more funding. Cleverly, he has recruited volunteer officials, or archaeological stewards, throughout the state. But the stewards have no real power other than to alert a property owner that his acreage is being plundered, and oftentimes they are regarded with suspicion. “A landowner will let a looter onto his place sooner than he’ll let a state archaeologist,” one steward admitted. “He’s afraid we’re going to condemn his property or something, which is ridiculous, but try telling him that. ”

Mallouf has little recourse but to monitor the looters’ activities and hope they will trip themselves up. Otherwise, they are certain to go unpunished. Laws in Arkansas and Oklahoma that make grave looting of any sort a felony have had the effect of driving pothunters in our neighboring states to ply their trade in Texas, where it is legal to dig up unmarked graves. Because Indians did not use headstones, Native American burial sites in Texas may be freely looted with the landowner’s permission. To address this, Mallouf’s office intends to introduce a bill this session similar to that of Oklahoma’s legislation.

In the meantime, the only statutes that specifically refer to pothunting in Texas are found in the Texas Antiquities Code, which decrees that people are not permitted to dig on public properties or on private sites designated as state landmarks. The penalty for violating the code is a misdemeanor fine of up to $ 1,000 and up to thirty days in jail. Few archaeologists can recall an instance where the code has been successfully enforced. Fewer still have ever heard of a landowner who has brought a pothunter to justice. Not long ago, a Lampasas justice of the peace approached a trespassing looter on his property and shot him in the leg. Not only did the justice fail to have the pothunter convicted for his crime but he in turn was sued by the looter for needlessly inflicting injury. As with Arnold Roitsch in northeast Texas, many landowners tire of endlessly chasing off unwelcome visitors and ultimately let diggers onto their land for a fee—$5 a head, $25 a day; whatever is offered is usually taken. “When the owner comes after me, I just hold up a hundred-dollar bill,” explained one pothunter to Bob Parvin, an amateur archaeologist in Austin. “I tell him, ‘You can either spend your hard-earned money trying to prosecute me or you can take this hundred-dollar bill and let me go about my business.’”

“I’ve been working with landowners for the last twenty years,” Mallouf told me with obvious weariness. “In order to prosecute pothunters for criminal trespassing or destruction of private property, you have to catch them in the act. It’s hard to do, and besides, for the most part, we’ve had a difficult time interesting the law enforcement community in this problem. Even on public lands, when we’ve had flagrant violations of the antiquities code, the district attorney will just throw the case out.”

More typically, Mallouf and others told me, local officials are backlogged with felony cases and see arrowhead digging as unworthy of their energies—except, of course, when it is they who are doing the digging. When Joe Labadie was hired as an archaeologist at the Amistad National Recreation area in 1987, he was chagrined to discover how much looting was taking place in the area—and doubly chagrined to discover that federal officers working there were engaging in surface collecting themselves. San Antonio archaeological steward Ray Smith finally got tired of hectoring an officer in the Uvalde area who looted private property for arrowheads. Changing his approach, Smith handed the officer a topographical map and persuaded him to at least record, for historical purposes, the sites he was pillaging.

Smith’s eyes narrow with disgust when he talks about looters. But what especially eats at him is that they know things he doesn’t. “I’m in touch with about three dozen hard-core pothunters,” he told me. “One of them came to me the other day and told me he’d found a Folsom point that came from a bank in a Bexar County creekbed. He said he happened upon a lot of bones. I said to him, ‘You know what you’ve come across, don’t you?’ He said, ‘Sure do. A mastodon kill site.’ So I’ve got to work on him. I’ve got to see that site.”

When archaeologists such as Smith talk about pothunters, their hostility is tempered by reluctant envy. After all, the archaeologist pursues a nobler course: carefully excavating, recording all findings, examining skeletal remains for signs of diseases, studying teeth for nutritional information, sifting through dirt to determine the temperatures of the ages. Labor burdened by conscience is tedious work. “It takes us years to excavate a midden site,” he pointed out. “It takes them a couple of weekends. They hire a couple of wetbacks to do the digging, break even as soon as they’ve found a couple of spear points, grab everything there is to get, and move on to the next place.”

As looters plow through Texas with unbelievable speed, it is all the archaeologists can do to follow behind, examining what bones the pothunters are willing to throw them before all prehistoric history vanishes from the state for good. “Like it or not, they’re doing more digging than we are,” Joe Labadie reminded me. “We’ve got to maintain amicable ties.”

Every archaeologist I spoke with echoed Labadie’s sentiments. For many of them, the partnership is uneasy but necessary. Other archaeologists plainly sympathize with the temptations to which looters succumb: Some of the state’s most distinguished archaeology professors are themselves former pothunters. Talk of jail sentences hits too close to home; they prefer the evangelical approach over the punitive.

Whatever the logic of their position, its effect is to legitimize looters and thereby hasten the disappearance of our state’s unwritten history. What such a loss would mean to Texas is hard to gauge. But gauge we must, rather than rip like human buzz saws through all that is gray and inexplicit, reducing culturally profound tokens to their most trivial denomination. By not acting to stop the pothunter, we condone his ethic and sever our connection to the soil that defines us. Otherwise, Texas should do all it can to banish looters to some other state where heritage means less to its residents than it does to us. The proposed law to protect unmarked burial sites should be passed. The state archaeologist’s office should focus its attention not on field research—which can be left to the dozens of Texas archaeologists presently looking for work—but on public relations to place the looter alongside other criminals in the Texan’s consciousness. The names of pothunters should be turned over to the IRS. Archaeological stewards should pressure police forces in urban areas to assign an officer to patrol sites, as has already happened in Austin. (“One full-time law enforcement official in East Texas would be a massive improvement,” Nacogdoches archaeological steward Tom Middlebrook told me.) Members of the academic community should quit ingratiating themselves to thieves and vandals. They should persuade judges and district attorneys to accompany them on surveys of devastated properties and offer to turn in the perpetrators.

Above all, Texans who cherish their property should ask themselves if they have loved their land all these years only because it is theirs—or if, perhaps, because there is something in the land that speaks to them. If it is that voice they love, then they must see to it that the voice is never silenced.

There is a spot on my family’s ranch that I have traversed for decades, heedless of its significance until the day Jeff Merkord came to visit. Together we walked through this particular area, and, for the first time, I saw them: fire-cracked rocks. “It’s a midden,” Merkord told me, and indeed it was, far removed from the others, wedged among a thicket of trees and, for now, undisturbed.

I don’t know what’s in there. In the looter’s dim fantasies, the site might yield another rare corner tang or perhaps even a ceremonial pipe. In all likelihood, though, it would contain nothing more than a handful of points, worth $50 at the arrowhead shop in Wimberley—good for a couple of days’ worth of food and booze, and then on to the next property. But I have other plans for this midden. Once a week I’ll bring a large bag of sugar to this spot and spread its contents evenly on the surface. Then I’ll sit off to the side and slowly recede into my memories of the valley, breathing the little boy’s short breaths while the fire ants gather upon the midden and stand guard over the slumbering ghosts.

- More About:

- Texas History

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Hill Country