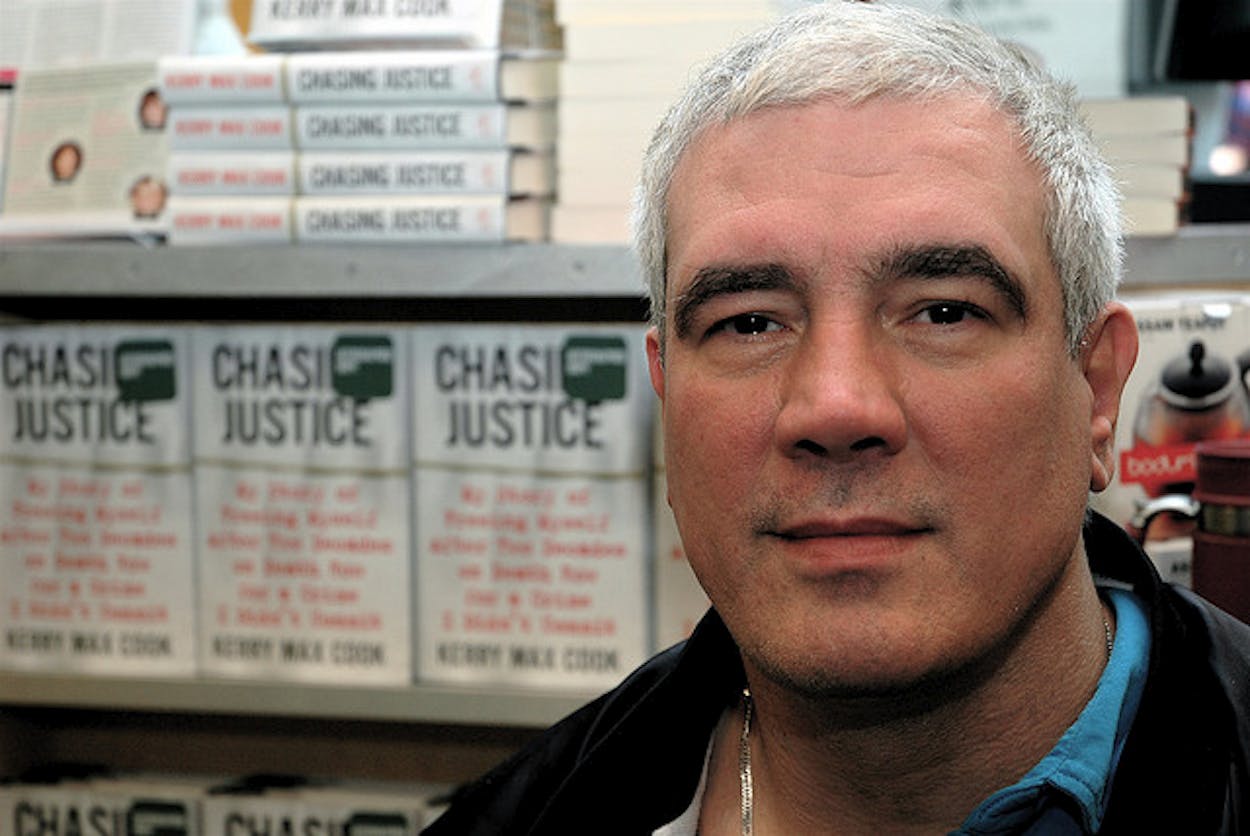

Editor’s note: David Hanners, a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter for the Dallas Morning News, wrote more than forty stories about the Kerry Max Cook case, starting in 1988, and broke much of the news that is now used by Cook’s lawyers and supporters as evidence of his innocence. Hanners won a Gavel Award from the State Bar of Texas for his coverage of Cook. He currently writes for the Pioneer Press in St. Paul, Minnesota. This is his response to Michael Hall’s post from March 2 about the Tyler Morning Telegraph‘s coverage of the latest dramatic developments in Cook’s case.

As the reporter for the Dallas Morning News whose stories initially raised doubts about Kerry Max Cook’s guilt, I believe I have a few observations I can offer to the discussion.

The first would be that when it comes to Mr. Cook’s saga–and there’s no other word for it–the Tyler Morning Telegraph has never acquitted itself well. As a journalist myself, I am usually hesitant to disparage another journalist or publication, but the Tyler paper’s history of coverage in this case has been a sad entry in the annals of objective and fair journalism. There’s just no other way to put it. The paper has, time after time, taken the word of local police and prosecutors as gospel in Mr. Cook’s case and has done little, if any, original journalism. And, as the record reflects time after time, the word of police and prosecutors in this case has not been worth much.

I am probably one of the few people who has gone into Mr. Cook’s case with objective eyes. When I began looking into it, I wasn’t out to prove him guilty or innocent; frankly, I didn’t care. My reason for looking into his case was to try and answer a very simple question involving the administration of justice: Why did it take the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals nearly eight years to rule in his initial appeal? At the time, that was the second-longest pendency of an initial appeal in the nation, and it was a legitimate question. (As I would later find out, it was because the court basically lost the file.) At that stage, whether he was guilty or innocent really didn’t matter to me. I didn’t have a dog in that particular fight.

But as I sat in the basement of the Supreme Court Building and read Mr. Cook’s trial transcript and looked through the trial exhibits, it became increasingly clear to me that at the very least, he had not received a fair trial and may well have been innocent. The state’s case against him, skinned of the graphic courtroom theatrics employed by the prosecution, just didn’t hold up to even the lightest scrutiny. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals would eventually come around to that view, too. And I believe in time more people will become convinced of his actual innocence.

I just don’t believe Kerry Max Cook killed Linda Jo Edwards. In discussing this case with others, I have often described it as Murphy’s Law personified; everything that could go wrong, did. The initial police investigation was hopelessly incompetent and relied on pseudo-science that was bad even for 1976. The police didn’t do what a basic police investigation would have or could have done–on some things, the police went to great lengths, while they left unturned stones that were right in front of them. As an example of this irony, consider that the cops went all the way out to the East Coast to interview Ms. Edwards’ ex-husband (he was in the military at the time of the murder) but the police couldn’t be bothered to drive out to the campus of what was then Texas Eastern University to interview people who worked with the victim, as well as people who knew Jim Mayfield, the man identified by Ms. Edwards’ roommate as being the person she saw in the apartment.

The majority of murder victims are killed by people they know, and interviewing those closest to the victim (and to the initial suspect) is Homicide Investigation 101. When those co-workers complained to the police about not being talked to, the detectives went out to the school and basically waited for people to come to them–in full view of Mr. Mayfield.

Examples abound of the ineptitude of the police investigation of Ms. Edwards’ death. Consider the “missing” stocking. Police said they found only one stocking at the scene, and so the prosecution turned that “theft” into one of the elements that made the case a capital crime. The description the prosecutor offered at Mr. Cook’s trial was quite graphic: After killing Ms. Edwards, the killer allegedly cut out body parts and stuffed them in the stocking and took them as “trophies” of his kill. Imagine sitting on the jury and hearing that, unrefuted by the defense. Well, as we would later discover, no body parts were ever taken and no stocking was missing; the cops were just too incompetent to find it. When the jurors in the first retrial had the trial exhibits back in the jury room, they opened the sealed evidence bag containing Ms. Edwards’ jeans, pulled them out and held them up. The “missing” stocking dropped out. The cops couldn’t even find a stocking in a pant leg.

That type of conduct permeates the police investigation, so it is legitimate to question how anyone can have any faith in it. Still, the “he-took-body-parts-in-a-stocking” bit remains part of the accepted mythology surrounding this case.

I’ve covered many murder cases over the years (I’m even in the midst of covering one now as I write this), and I know full well they often rest on circumstantial evidence. But even the circumstantial evidence in this case had to be stretched–and in some cases fabricated–to win a conviction. To combat that, Mr. Cook’s initial defense team did little to nothing in the way of investigation, or at least the type of investigation you’d like to see in a capital murder case.

Over the years, I have developed my own theory of who was involved in Ms. Edwards’ murder. I’ve shared it with both sides. It is a theory that fits the available evidence (direct and circumstantial) and is not inconsistent with the known facts. I’ll not share that theory here, but suffice to say that it doesn’t involve Mr. Cook.

Not to put too fine a point on it–and this is something I’ve spoken to Mr. Cook about, so he knows what I’m about to say–but Mr. Cook was not a good enough criminal or a lucky enough criminal to have committed a crime of this fury and magnitude and NOT leave a ton of evidence. He was young, immature, impulsive, and just didn’t think that far ahead. While that made him sloppy, it did not make him a killer. As “iffy” as fingerprints can be, he could not have committed this crime and not left bloody fingerprints or footprints everywhere in that apartment. If you study the state’s case and count up the number of things he is supposed to have touched in the apartment before, during and after the crime, the statistical probability of him not leaving a fingerprint or smudge of some sort climbs a lot higher than I can count.

I also wish to speak to the DNA evidence and the way the prosecution has handled it. I clearly remember David Dobbs, the prosecutor handling the retrials, telling me prior to the testing that they were excited about the prospects of a test because the semen sample “could only have been left by the killer.” Those were his exact words to me, and I remember him saying it as if it were yesterday. So then the sample is sent away for testing, the deal with Mr. Cook is offered and accepted–and then the results come back showing the semen belonged to someone other than Mr. Cook. Suddenly, the prosecution’s story changes. Now they say, “Well, of course it was somebody else. But Mr. Cook is still the killer.”

That last point is emblematic of how the police and prosecution have behaved over the lifetime of this case. When it came to what the evidence showed, they have wanted to have it both ways. When they claimed the evidence said one thing, they said it pointed to Mr. Cook’s guilt. When it was proven the evidence said the opposite, they said it still proved Mr. Cook’s guilt. Like I said, you can’t have it both ways.

Absent confessions from those involved in the murder, I doubt we’ll ever know for sure what happened to Ms. Edwards. The investigation was so screwed up that it can’t be trusted, and you don’t get a do-over when it comes to collecting evidence from the scene of a 1977* crime. Mr. Cook deserves more than what the system has given him. For that matter, Ms. Edwards deserves more than what the system has given her. She, like Mr. Cook and justice itself, deserves the truth, and we do them all a disservice by perpetuating the lies that led to this ugly conviction.

*Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated the year the crime took place. It happened in 1977, not 1976 as we previously reported. We regret the error.