This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

I’ve never attended a time-management seminar, but I’ve read enough books and articles on the subject to conclude that such schemes have little to do with the life I lead. I have tried listing priorities and setting goals. I even have an indexed notebook, which I have left more times than I care to remember at the check-cashing window at Safeway. I balk, however, at the suggestion that I brown thirteen pounds of hamburger meat in my turkey roaster to make twelve freeze-ahead casseroles. Who are the children who eat Crunchy Hamburger Noodle Bake?

The only regular ordering of my day comes when my attorney husband leaves the house at about eight-fifteen. His mind is already fixed firmly on a day that is divided on his desk calendar into hourly appointments. I have visited his office and seen little yellow slips of paper lined up on his desk awaiting his disciplined and rarely interrupted dispatch. Briefcase in hand, he invariably turns as he goes out the door and says, as if dictating a memo, “If you have time today, could you do as follows: (a) get my blue pants at the cleaners, (b) call about tennis lessons for Jack, (c) figure all the sales tax on the checks in last month’s bank statement?”

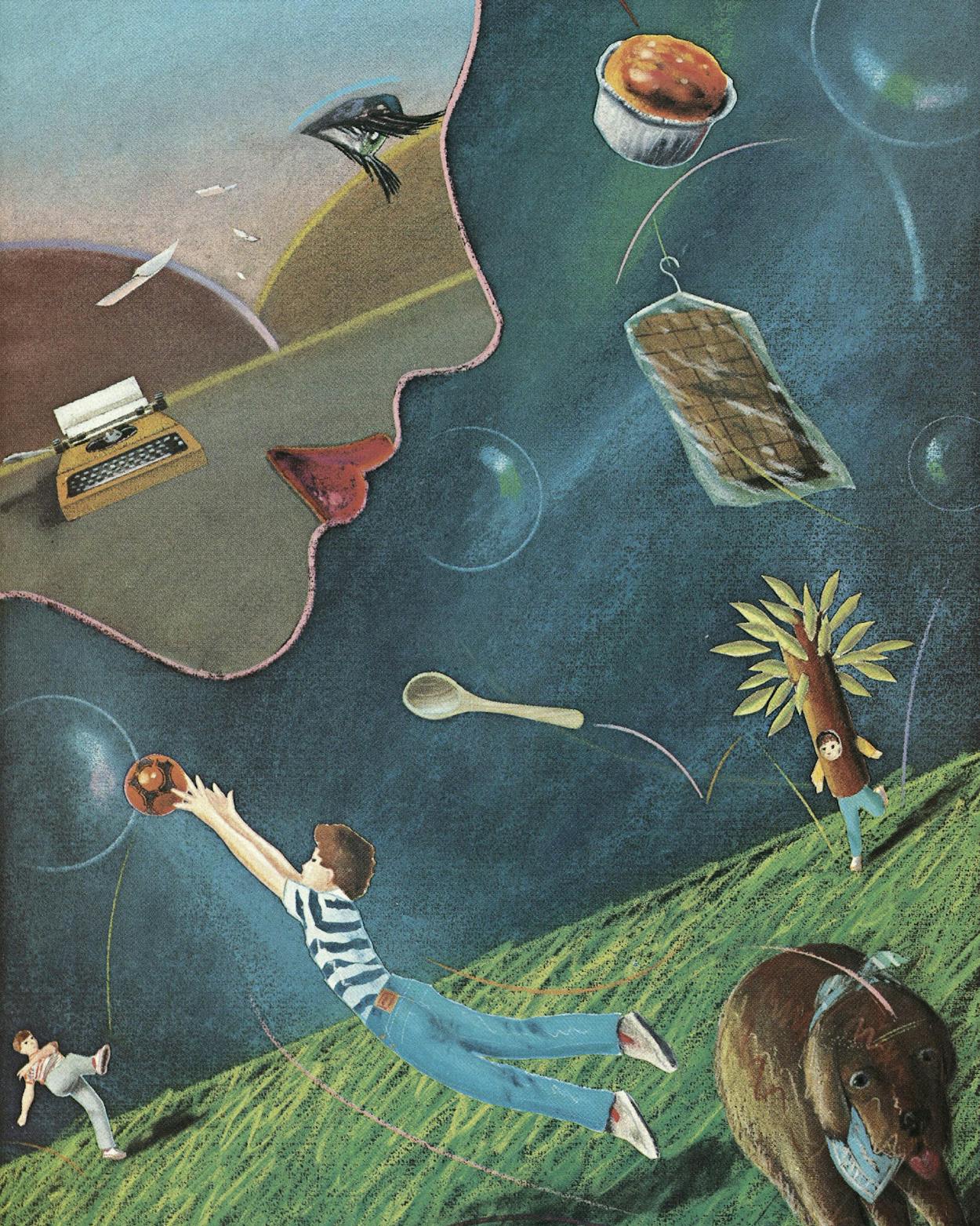

I laugh and reply, “Moreover, by copy of this letter all other counsel of record will be provided a copy of the above. In addition, please add section (d): measure out life in coffee spoons.” My day began two hours ago, and I can already recount triumphs and small disasters that time-management experts never anticipate.

My job as a writer does not come with a downtown office, a supervisor, or a time clock. The need to write hovers around the edges of my more insistent vocation—mothering.

Daily, small people clamor at my elbow for clean socks, meals, mediation, lunch money, crazy eights, and chauffeur service. Editors intrude less than once a month, and then only by long distance.

“There will be time—eons of time—when your children are grown,” says the internist who diagnoses my stress from time to time. He doesn’t understand that in my case one vocation feeds the other. Although being the mother and the writer makes my life complicated and often inefficient, I want to write from experiences I’m having now. Children are not items on a list, to be scratched off when finished. They are never quite finished, and life with them must be appreciated in the process. Writing helps me step back and notice the process.

“I know you’re writing every day,” an artist-mother confides, “and I want to know how you do it, because I’m not painting.” The doctor’s promise that someday there will be time does not assuage her, either. “The painting,” she says, “it’s like an itch in the middle of my back that I can’t quite reach. And if I ignore it, postpone it, it becomes something that I’m not even sure I can do anymore.” We both agree that playing Bach at the piano helps.

Most mothers caught up in the minutiae of life with small children live with the frustrating illusion that in other houses mothers with more discipline who need less sleep are proceeding through a carefully balanced day full of uninterrupted intellectual pursuit that enables them to have a sense of real accomplishment at the end of the day. Somewhere, perhaps, but not here.

We stayed up far too late last night reviewing the characteristics of the phylum Echinodermata with Jack, our seventh grader. I was slaphappy by ten-thirty as we dramatized the weird defense mechanisms of the sea cucumber. The ultimate riposte: when attacked, the sea cucumber can eject its intestines into the face of its assailant. I don’t remember having seventh-grade biology on my priority list, but it left no time to wash my hair. I set the alarm for six, hoping to shower before breakfast and perhaps to make notes on a magazine article I had outlined last November.

My youngest son, William, who is six, awakens me five minutes before the alarm goes off. “Have I got a dream for you!” he announces. His father plays academy award possum, obviously relishing his favorite predawn fishing fantasy, which we call “Gone to Port O’Connor to Catch the Big One.” I muzzle William (who has no whispering voice), forgo the shower, and head for the kitchen to make coffee before settling in for a play-by-play account of a witch who kidnaps William and his brothers, locking them in a room lined with stuffed animals that have laser eyes. One look at the snake’s laser eyes and you turn into a stone deer. (Here I detect some mingling of Saturday morning cartoons and C. S. Lewis’ The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.) The dream, of course, has a heroic ending. The witch gives William a present that he instinctively knows is a bomb. He hurls it at the witch and all the stuffed animals and—kaboooom!—his brothers are saved.

Perhaps I am the witch. As Rosie the dog and I go out to fetch the morning paper, I see that Drew, the ten-year-old, has once again left his new bicycle unlocked in the yard. I note on the calendar when he’ll be allowed to ride it again. Bookkeeping on the transgressions of three sons does get tedious.

At breakfast, which despite my best-laid plans is always served short-order style, I succeed in getting our almost-adolescent to eat a scrambled egg. I never intended to become the sort of mother who nags about nutrition, but as other convictions are worn away it’s comforting to know that my epitaph can still read: “She never bought presweetened cereals.” Nevertheless, the seventh grader’s diet usually consists of cereal for breakfast, four Nutty Buddies for lunch in the school cafeteria (I don’t know who eats the sandwich and apple he packs every morning), and who knows what contraband in the afternoon while I’m chauffeuring his brothers to soccer and music lessons. An egg and orange juice on a Monday morning represent a major triumph.

William ordinarily attends afternoon kindergarten, but today he has to rehearse with the morning class for the back-to-school program. As we dash to the school after his brothers have departed, I remember that Jack’s gym clothes are still in the dryer. Failure to suit up means he gets what the coach at middle school calls the palm leaf. “How we gonna teach your boys any responsibility if you keep lettin’ ’em play you like a yo-yo, bringing those gym suits up here when they forget ’em?” the coach says to parents every year at open house. I don’t know. I’m the mother who refuses to accept the laundry responsibility until late Sunday night when nobody has clean socks. I decide to let him take the palm-leaf paddling anyway. Duck wings and angel halos need adjusting in the kindergarten.

At the elementary school, costumed children are too excited to follow instructions from any adult. The rehearsal is delayed because one small boy is cowering in the rest room. He is the only male duck and has just learned this morning that his costume is a yellow leotard with orange tights. I enter the boys’ rest room with Sue, another mother of sons, to counsel with him. “I can’t let anybody see me like this,” he says, tears spilling down his cheeks. Sue and I, sympathetic to the fact that he has older brothers in the school, look at each other and agree, “No, he can’t.” I find his blue jeans in his locker, and when the time comes for Daddy Duck to summon his three little ducklings with a quack-quack-quack, no one seems to mind that beneath his wings he’s wearing Levi’s.

After some minor footlight adjustments the rehearsal goes on. I take a seat in the auditorium and make a note to pick up camera film. This is my last baby’s kindergarten show, and even though he has been cast as a rubber-tree plant, we’ll join the rest of the fools with flash attachments tomorrow night. I wonder if Hector’s mother knows that despite her son’s adorable jack-in-the-box costume he will spend most of the program hidden in the box.

What is it about little girls on-stage? My boy child sings a few lines, then hitches up his pants, examines the contents of his nose, and seems a little slack-jawed for the rest of the rehearsal. The girls, in sharp contrast, have real stage presence. Not only do they make eye contact and know all the words to their songs but they sing everyone else’s songs and point out to the teacher that Hector is not singing in that box. They have to be told several times to stop doing the motions to other people’s parts.

I marvel at the talents of the mothers who have made costumes. Who would have guessed that with some spray insulation and Styrofoam teeth a baseball helmet could be turned into a hippopotamus head?

The rehearsal is over by ten-thirty. William invites Ben, another rubber-tree plant, to come home with us. I stop at the grocery store on the way home, and as we walk past the cleaners, I remember that I’ve left John’s cleaning on the bench in the hall. I never make one trip to this shopping center when two or three in one day are possible. Since I’ve bought nothing at the store that will melt, I stop at the do-it-yourself car wash on the way home to get some of last night’s dust storm off the car. I regret that I’m wearing my only pair of new spring shoes, but the car really does look as if it’s been to Lubbock. As I’m racing around the car with the spray wand, one of the rubber-tree plants rolls down his window to ask me a question and I flood the back seat of the station wagon.

Once I’ve unloaded the groceries, I announce to the boys that we’re going to the park for a picnic lunch. I never got the breakfast dishes done, and I can’t stand to add to the mess by fixing lunch at home.

It’s a gorgeous day in the park. We haven’t been here since the summer. Poor William. As third son he has rarely been to the park at all. The scenery has changed a little since my last visit. Today the park is empty except for two young men with their toddler daughters. The men’s bicycles are even outfitted with baby seats. From my picnic quilt I observe that these fathers are just as competitive as mothers, comparing notes on how soon their babies walked and how many words they can now say. The men finally grow weary of fetching the curious, staggering pair, who are intent on heading for the creek. They call time-out to finish their conversation and plop the tots in the sandpile cylinder. My rubber-tree plants swallow their sandwiches, leave me the crusts, and race off to swing and play pretend games that they seldom get away with in the presence of their older brothers. Drew was probably right when he said, “Childhood for William just isn’t what it used to be.” Both boys return thirsty and complain that this isn’t much of a picnic since I have only water to offer. I promise that we’ll get to school early enough for a frozen yogurt in the cafeteria.

We deposit the picnic basket at home, and I lock the dog in her pen in the back yard. I expect her to go into heat any day now and worry that the huge Labrador down the street may know it before I do. I slam the gate shut, raking the heads off my husband’s onion sets. He refuses to accept that his garden plot is now the dog’s pen.

In the school cafeteria the boys get their dessert, and I spot the mother of the child who delivered the Girl Scout cookies while we were out of town. We both have trouble figuring the cost of three boxes of cookies at $1.25 a box. Drew’s fourth-grade teacher approaches as I dispatch the rubber trees to their class. “Drew and I have had our wires crossed this week,” she tells me, and as if I didn’t get the euphemism, she adds, “His attitude is very bad.” I assure her that I’m not too fond of his attitude either and encourage her to stay on his case. He has never been highly motivated to do extra work. Only last week he learned the word “mediocre” and now says he thinks it’s what he’d like to be.

I stop back at the house, just to be sure the dog is not waltzing with the Lab in her pen. She seems content, so I toss the forgotten cleaning into the car and drive to Sanger Harris to check on an advertised rug sale. I have to park a block away and can’t resist stopping in at a sportswear shop to try on bathing suits. I haven’t bought a new suit in five years, so it takes courage after perusing the scanty pasties at the front of the shop to ask if anyone still makes a bathing suit with a built-in bra. The saleswoman directs me to some skirted numbers in the back of the store that come no smaller than size 16. I leave without trying anything on.

As I suspected, the rugs in the department store are on sale for good reason. They’re ugly. Pulling out of the parking lot, I remember that Jack still needs a chemical for his science project on photosynthesis. If a toy store sells chemistry sets, it follows that it might also sell replacement chemicals. The toy store clerk is certain that the test solution I’m looking for is sodium iodide. I take his word for it, since the section of my brain labeled “Chemistry 601” is vacant except for the word “valence” and a few fond memories of an Australian lab instructor. I am elated to have escaped with this small bottle for a dollar. I was fully prepared to buy a whole chemistry set in desperation.

I remember to take the clothes to the cleaners this time. As I sort out the bundle on the counter, I notice that it contains the coat to the suit pants I’m picking up.

A new bakery has opened in the shopping strip, so on impulse I buy pain de campagne and five chocolate eclairs that will make the frozen pizza we’re having for dinner tonight more palatable. At the drugstore I remember to buy poster board. Who can do a science project without poster board? I forget to buy the camera film.

John calls when I get home. He wants to know if I’ve done three things he wrote down on a To Do list for me. I scan the kitchen area near the phone for some scrap of paper he’s left me, then confess, “No, I haven’t called Texaco to get them to send us a copy of our last two statements, and no, I haven’t called the insurance company about the appraisal, and no, I haven’t RSVP’d on the invitation to tour the unfinished art museum, but I’ll get right on it.”

I don’t. Instead, I remember to release Jack’s geranium plants from the dark closet where they’ve been languishing for lack of sunlight in the name of science. Since there won’t be two hours of sunlight after Jack gets home from school, I start the project for him by cutting strips of black paper, paper-clipping them to the leaves, and, finally, putting the droopy plants in the sunniest window.

Three-fifteen. Time to meet William at the school crossing. I put the dog on the leash and run the half-block for what I call aerobic awareness (it makes me aware that I’m breathless after running half a block). Back home again, William eats a Popsicle while I sort through the huge stack of mail that has dropped through the mail slot. I extract the phone bill and dump the rest in the trash. The two older boys come in the back door at fifteen-minute intervals. I try to monitor the amount they eat while they give me a cursory rundown on their respective days. Drew assures me that he and his teacher have made up. I warn him that he should not go to Todd’s house to play Atari, since he has a music lesson at five-thirty and needs to practice. He’s not afraid of his music teacher, but I am.

Jack is relieved and genuinely grateful to see my progress on his science project. He rereads his experiment at his desk and yells downstairs, “Do we have any denatured alcohol?” Ooooh, and I thought we could get by with isopropyl. I call the pharmacist, who says, “You know, lady, we get a lot of calls for that, but we don’t carry it. Maybe a hardware store would have it.” I make a note to stop at the hardware store after I drop Drew off at his music lesson, but first I have to find William’s soccer kneepads.

The dog has chewed one kneepad, but when William stuffs it under his long sock, it doesn’t show. Last week was William’s first soccer game against the Blue Mean Machine, and his team won. William never came within twenty feet of the ball, but he now thinks he’s some kind of Pelé. “The Gold Stallions are gonna cremate the White Knights,” he growls as I drive him to the soccer field. I reintroduce him to his coach, since William says the coach called him Bill last week. I also locate two little friends of his for security and then explain that Mommy has to take Drew to music and Daddy will arrive before the game is over to take him home. He won’t buy it. He clings to my skirt and says, “You can’t go till Daddy gets here.” Fortunately Daddy does arrive. He kisses me right there on the field, even though he knows in his heart that I haven’t called Texaco, the insurance company, or the museum. “I never saw anybody get kissed on the soccer field,” comments the mother of a White Knight.

I dash off to get Drew, who in my absence has, of course, escaped across the alley to play video games at Todd’s. I squeal into the driveway, grab the evening paper out of the yard, and honk Drew out of the neighbor’s house. Halfway to the music lesson he confesses that he has let the dog out and that he saw her playing with the huge Lab. He promises to call Jack when he gets to his lesson, since I have to get to the hardware store before closing time and the bank clock reads 5:53. The hardware store manager is locking up as I arrive, but seeing the desperate look on my face, he allows me to purchase my denatured alcohol. I pick up some milk at Tom Thumb and still have ten minutes in front of the music teacher’s house to scan the Times Herald. The musician emerges, and halfway home he admits that he forgot to call Jack about the dog.

As we approach our block, I see a police squad car pulling away. Jack is still shaky from the officer’s visit. “He brought Rosie up to the door, and he wanted to talk to you. He said he’s gotten complaints about this dog from the neighbors, and Rosie kept making it worse by barking and snarling at him like some mad dog. I thought he was going to arrest me.”

John and William return from the soccer game victorious. John takes one look at the desultory frozen pizza and suggests that we all could do with a Mexican-food fix. Jack says he has too much homework, but fearing that he’ll eat another Nutty Buddy for dinner if we leave him at home, I insist that he take his spelling homework to the restaurant. Drew dashes upstairs to get some quarters out of his bank in hopes that we’ll choose an establishment that has games.

Once we’re seated in the restaurant, John forbids anybody to leave the table, then curses the whole video-game industry, which would invade his pleasant family evening of chiles rellenos and Dos Equis. While John and I try to review our respective days, the older boys interrupt intermittently to point out what they believe to be homosexuals, transvestites, and hermaphrodites dining in this family restaurant. William studies a man with no teeth who is gumming his tostada. I discourage their staring and show them a clipping about their mom that appeared in my hometown paper. I like to remind them from time to time that I have a vocation quite apart from their science projects and dirty socks. “Why do they keep calling you Ms. Mackintosh in this stupid story?” one wants to know. “Do you have multiple sclerosis?”

Home again. Standing up in the kitchen, we eat the lovely chocolate eclairs. I notice that the roaches are letting me down again by coming out when the lights are on. I make a note to call Mr. Thunderbugger.

The small soccer champ is on the verge of hysterical fatigue, so before his older brothers nail him, I dispatch him to the bathtub for a little hydrotherapy. “Read me that book about Bevo,” he says as I tuck him in for the night.

“We don’t have a book about Bevo, do we?” I answer, scanning his bookshelves in search of cowboys, cattle drives, or UT football rituals.

“This one,” he says, knocking a stack to the floor.

“But this one is about how babies are born.”

“It’s still got a picture of Bevo on the second page,” he insists.

He’s right. The drawing of the uterus and ovaries on page 2 does look remarkably like a Longhorn. I promise that we’ll read this one in the morning.

“Then do the prayer about moon and sun and hills,” he says. For a child whose religious education has been thoroughly muddled by his older brothers (he thinks Abraham and Moses have the last names “Lincoln” and “Malone”), this son is always comforted by the language of the King James Bible. Or perhaps he’s just an adept con man who knows that he can persuade his Southern Baptist–reared mom to linger at bedtime with a show-off performance of “The sun shall not smite thee by day, nor the moon by night.”

Meanwhile, Jack waits in the kitchen to begin the serious laboratory work on the geranium leaves. The denatured alcohol bleaches the leaf nicely, but sodium iodide fails to do its part. Checking my watch, I see regrettably that there is still time for a run to the pharmacy to get some tincture of iodine. Another mother in the drugstore offers her sympathy. Her family has recently purchased an incubator and sacrificed the past three weekends to drive to Pittsburg, Texas, to buy fertilized chicken eggs for a high school science project.

Back in the kitchen, we start the pots boiling again. Rosie the dog has wisely passed out at my feet, and I do feel foolish cooking geranium leaves at nine-thirty. Eureka! Tincture of iodine works. The bleached leaf turns blue, verifying what mankind has probably known since the Enlightenment: plants contain starch. Still, we make everyone except sleeping William come downstairs to witness our triumph.

The young scientist is sent to bed, while I examine the yellow iodine stains on my nails and counter tiles. Collapsing in the kitchen rocking chair, I reach for my journal to make sense of a particularly fragmented day. Accomplishments: Jack ate an egg. The dog is not pregnant. The Girl Scout cookies are paid for. The science project—not mine, of course—is completed.

The time-management expert is not amused. What sort of report card is this? Surely there is more. Yes, some musings on the nature of kindergarteners, young fathers in the park, and the uneven growth of three sons: the baby who can “cremate the White Knights” but still clings to his mother’s skirt, the “mediocre” middle son who currently resists learning that talent without drive is worthless, the firstborn who shows some promising signs of a grateful heart. But what about the writing? The notes scribbled on three-by-five cards during the recounting of dreams, after soccer, and before music lessons will eventually take shape. This sort of life is not without precedent, you know. Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote in this letter to her sister 133 years ago:

So this same sink lingered in a precarious state for some weeks, and when I had nothing else to do,

I used to call and do what I could in the way of enlisting the good man’s sympathies in its behalf.

How many times I have been in and seated myself in one of the old rocking-chairs, and talked first of the news of the day, the railroad, the last proceedings in Congress, the probabilities about the millennium, and thus brought the conversation by little and little round to my sink! . . . because, till the sink was done, the pump could not be put up, and we couldn’t have any rain-water. Sometimes my courage would quite fail me to introduce the subject, and I would talk of everything else, turn and get out of the shop, and then turn back as if a thought had just struck my mind, and say: —

“Oh, Mr. Titcomb! about that sink?”

“Yes, ma’am, I was thinking about going down street this afternoon to look out stuff for it.”

“Yes, sir, if you would be good enough to get it done as soon as possible; we are in great need of it.”

“I think there’s no hurry. I believe we are going to have a dry time now, so that you could not catch any water, and you won’t need a pump at present.”

These negotiations extended from the first of June to the first of July, and at last my sink was completed. . . . Also during this time good Mrs. Mitchell and myself made two sofas, or lounges, a barrel chair, divers bedspreads, pillow cases, pillows, bolsters, mattresses; we painted rooms; we revarnished furniture; we—what didn’t we do?

Then on came Mr. Stowe; and then came the eighth of July and my little Charley [her seventh child], I was really glad for an excuse to lie in bed, for I was full tired, I can assure you. Well, I was what folks call very comfortable for two weeks, when my nurse had to leave me. . . .

During this time I have employed my leisure hours in making up my engagements with newspaper editors. I have written more than anybody, or I myself, would have thought. I have taught an hour a day in our school, and I have read two hours every evening to the children. The children study English history in school, and I am reading Scott’s historic novels in their order . . . ; yet I am constantly pursued and haunted by the idea that I don’t do anything. Since I began this note I have been called off at least a dozen times; once for the fish-man, to buy a codfish; once to see a man who had brought me some barrels of apples; once to see a book-man; then to Mrs. Upham, to see about a drawing I promised to make for her; then to nurse the baby; then into the kitchen to make a chowder for dinner; and now I am at it again, for nothing but deadly determination enables me ever to write; it is rowing against wind and tide. . . .

To tell the truth, dear, I am getting tired; my neck and back ache, and I must come to a close.

Harriet always keeps me from feeling heroic or even modern. A little less than a year after Mr. Titcomb fixed Mrs. Stowe’s sink, the first installment of Uncle Tom’s Cabin appeared.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Dallas