This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Hiding the Ball

Tuesday, May 11, en route to Boston

On the bright, crisp morning of May 11, promptly at ten o’clock, T. Boone Pickens, Jr., the founder, president, and chairman of the board of Mesa Petroleum Company, stepped aboard a private plane at Houston’s Hobby Airport. Under his arm was a thick folder stuffed with papers and documents, and behind him trailed an aide carrying several more folders bulging with papers. The plane, a sleep Falcon nine-seat jet, cream-colored with blue trim, was one of two corporate jets owned by Mesa Petroleum, and on this day it was carrying Boone Pickens to Boston, where he was scheduled to deliver an address to a convention of financial analysts.

The middle of May was not the best time for Pickens to have a speech on his agenda; he was excruciatingly busy. Two days before the trip, he had cut short a weekend at his ranch near Pampa to attend a late Sunday afternoon meeting at the offices of Baker & Botts, the giant Houston law firm that does most of Mesa’s legal work. The next day, he canceled the top management meeting that is usually held every Monday at Mesa’s Amarillo headquarters, so that he could continue the Baker & Botts sessions. After the Boston speech and a dinner given in his honor by Morgan Stanley, a New York investment bank house, he planned to fly immediately to New York for still more meetings that would last into the night and through most of Wednesday. If Pickens could have divined a way to avoid the Boston trip, he probably would have done so.

But if there were good reasons for ducking the convention, there was a better one for attending: it was the best way to keep America’s oil analysts from knowing what he was up to. His concern was easy to understand. Because what analysts do is largely predictive in nature—their ultimate goal is to forecast for the investment houses that employ them whether a stock will go up or down—they are always on the lookout for that one tidbit, that rumor, that minute scrap of information that will give them an edge in predicting stock prices. As a result, analysts are, both by nature and by training, gossipmongers. And had Boone Pickens canceled his appearance at their convention, the rumors that had swirled around him for over a year would have gathered and swelled like a tornado. Every oil analyst in America would have had the same thought at the same moment: if Boone Pickens is so busy that he has to cancel his speech here, he must be planning something . . . he must be getting close to making a deal . . . he must be preparing to make a run at Cities Service Company! Which, of course, was exactly what Pickens was doing. Life in the oil business is a succession of deals, and if Pickens could pull this one off it would be the biggest and most daring deal of all. It would take him to the heady pinnacle of American finance, a strange, high-pressure world that has been seen up close by only a few hundred people. The rewards were potentially huge and so were the risks, and everybody would be watching to see if he stumbled.

When the Mesa jet had reached its cruising altitude, Pickens picked up a telephone that lay next to his armrest and called his office in Amarillo. “How’s the market today?” he asked.

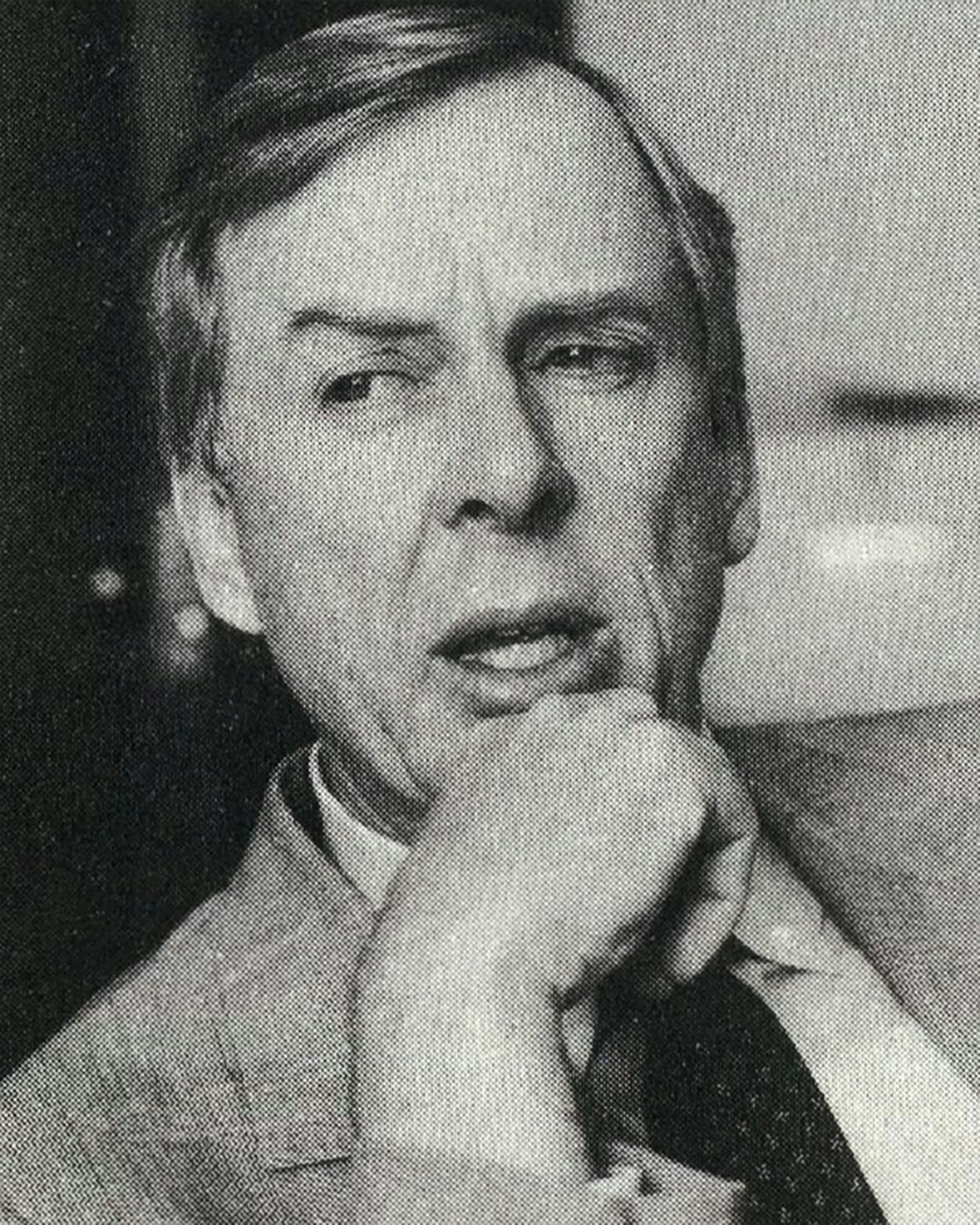

Although Pickens has practically been canonized on Wall Street for his shrewd financial dealings, he gives an impression of ordinariness. He does not exude charisma. He favors unostentatious business suits and shuns accoutrements like flashy rings and cowboy boots. At 54, he is obviously in good physical condition, but no one would ever mistake him for a 35-year-old: the hair around his ears is graying, and his face is lined with the creases of his age. His jowls sag. From certain angles, he bears a striking resemblance to our most uncharismatic president, Jimmy Carter. Being a Republican of the hard-rock variety, Pickens finds the comparison odious.

While the stock prices were being read to him, Pickens grabbed a piece of paper and began writing. “Mesa opened strong today,” he said and jotted down the number. 17 7/8. Then the Mesa Royalty Trust, a spin-off company he formed several years ago in a clever maneuver that gave stockholders ownership interest in several of Mesa’s oil properties: 27. He grunted approvingly. Then the opening stock quotations of the several independent oil companies he follows and the price of the cattle futures market, which he plays heavily. He wrote those down too.

After that conversation Pickens made a second call, this one to Alan Habacht, a partner in the New York investment firm of Weiss, Peck & Greer. Boone Pickens has always been an assiduous courter of the Alan Habachts of the world; even more than most chief executive officers, he wants to be on good terms with Wall Street. In Pickens’ mind, the courting has paid off: more than 50 per cent of Mesa’s stock is owned by institutional investors, a statistic that Pickens believes adds luster to his company’s reputation. Alan Habacht is among those on Wall Street who have known Pickens for years and think of him as a friend; more to the point, as an analyst for a firm that has controlled as much as 900,000 shares of Mesa stock, he is an important shareholder. Earlier that morning, Habacht had called Amarillo looking for Pickens, and now Pickens was returning the call.

“Hey, Alan, what’s going on?”

Habacht had one thing on his mind: Cities Service. What was Pickens doing? Was he going to make a move anytime soon?

It was no secret on Wall Street that Boone Pickens had long lusted after Cities Service, although at first glance it seemed an improbable dream. Cities was the 39th-largest company in America and the 19th-largest oil company; Mesa hadn’t yet cracked the Fortune 500. Cities had $6 billion in assets to Mesa’s $2 billion. By the measure of annual sales, Cities was twenty times larger than Mesa. But when Pickens looked at Cities, he saw not its size but its 307 million barrels of proven oil reserves, and the 10.6 million unexplored domestic acres on which it held the drilling rights, and, above all, its stock price, which was one third the estimated value of the company’s assets. What he saw, in other words, was an opportunity to find oil on Wall Street more cheaply than he could find it by drilling for it.

All this the analysts knew, but what they didn’t know was when or how—or even if—he could put together the kind of huge, complicated deal it would take to make a run at Cities. That’s just the way Pickens wanted it. For by the middle of May, after months of trying, he thought he finally had it figured out. Boone Pickens was going to try to buy Cities out from under its management by making what is called an unfriendly tender offer for the company’s stock—an open invitation to Cities’ shareholders to sell their shares to Mesa and, in so doing, put him in control of the company and kick out the old management. The deal he was putting together was indeed huge and complicated—and extremely unusual in the annals of Wall Street. It’s almost always the bigger company that goes after the smaller one; for the minnow to try to swallow the whale, as Pickens wanted to do, was unheard of.

By the time he went to Boston, a tentative launch date had been set for the Mesa tender offer: it was June 1, just three weeks away. The closer he got to that date, the more concerned Pickens became with secrecy. A tender offer is the business equivalent of war, and as in war, the element of surprise often can spell the difference between victory and defeat. So despite all the work yet to be done on the deal, Pickens preferred to throw away a day giving a speech in Boston rather than do something that might conceivably tip his hand.

As anyone who reads the business pages knows by now, Mesa Petroleum and Cities Service did indeed go to war this past June. The fighting lasted three weeks, the battleground was Wall Street, and the weapons were those of American finance. Boone Pickens did not win the war, inasmuch as he failed to gain control of Cities Service, but he didn’t really lose it either. The war ended on June 17, when the Gulf Oil Corporation stepped in and agreed to pay $5 billion to acquire Cities in a deal that would have been the third largest in history had it held up. When Gulf pulled out of the deal seven weeks later, Cities was locked into either finding a new multibillion-dollar buyer or liquidating itself. The moment it agreed to the Gulf deal, Cities lost any chance of remaining independent. That would not have been the case had Boone Pickens not tried so hard to buy Cities.

As to why Pickens went after Cities, that is harder to say for sure. The rewards could be tremendous: if he pulled it off, Pickens would be buying oil in the ground at the bargain basement price of $5.50 a barrel, and Mesa would instantly join the ranks of the second-tier oil companies. But the risks were equally large: if he lost this deal, he might lose Mesa, his life’s work. Even if he won, he would have to go more than $1 billion into debt. A number of analysts who watch Mesa for a living wondered out loud sometimes whether Cities was worth the risk.

But there was something else at work, something besides the cold logic of numbers and the assessment of risk. The fact is, Pickens loves making deals; they fuel him and excite him and challenge him in a way that the everyday business of his company does not. Perhaps even more than the successful search for oil and gas, Pickens’ ability to make good deals has been the key to Mesa’s rapid raise. I had tagged along with Pickens on this trip, as I would on all his travels for the next six weeks, and I asked him why he was pursuing Cities so doggedly. He proffered a wry smile, shrugged his shoulders, and said simply, “It’s time to make a deal.”

We live in the age of the corporate merger. Mergers have been with us for a long time, of course, but only in the last decade have they been perceived by the people running publicly held companies as a normal part of what it takes to do business. As recently as the sixties, takeovers were still thought of as exotic, and merger and acquisition strategies were unrefined and unsophisticated. Today, mergers are such a fixture that most companies large enough to be listed on the New York Stock Exchange have employees whose jobs consist solely of scouting out other companies that might make attractive acquisitions. Most of these same companies also have on retainer New York investment bankers and lawyers specializing in takeover law, just in case they decide to take the plunge and make an acquisition—or in case some other company tries to acquire them.

The image all this merger activity inevitably brings to mind is the game Pac-Man, with companies scurrying around in frantic search of other companies to gobble up, lest they themselves be gobbled. In the first half of 1982 there were 1198 mergers, which cost the acquiring companies $27.8 billion. The First Boston Corporation, an investment banking house that has the most aggressive and competitive mergers and acquisitions department on Wall Street, recently announced that in 1981 it had a hand in 39 mergers (costing the companies involved well over $22 billion)—an average of one deal every ten days. In the first five months of 1982, First Boston had already had a hand in 34 deals, or one every five days.

In the long run, many mergers have turned out badly for both parties, and they haven’t done the country as a whole much good either. In general, mergers don’t create new jobs, don’t do anything to expand the economy, don’t help make American business more competitive with foreign importers. They use up capital that could have been spent far more productively. But they continue to proliferate just the same, for reasons having to do as much with the culture of big business as with “economies of scale” or any of their other supposed dollars-and-cents benefits. Mergers are a quick and easy way for a company to get much bigger, and so they give an ambitious chief executive officer a means of expanding his empire. To the chief executive officer of a profitable, smooth-running company, for whom the daily routine has become humdrum, a merger play offers a chance for adventure. It is impossible not to get caught up in the excitement of a merger fight, to become exhilarated by the twenty-hour workdays spent with the smartest people in American business, to begin thinking, “There is nothing more important than what I’m doing right now.” The investment banking firm that most plays to this sense of executive machismo—First Boston—has also been the most successful at the merger game in recent years. But to some extent, all the various Wall Street institutions have made a great deal of money lately simply by pumping up the competitive instincts of American businessmen. Businessmen like T. Boone Pickens, Jr., Wall Street’s favorite oilman.

Friends

Wednesday, May 19, Houston

Boone Pickens harbored a special contempt for Cities Service. In Pickens’ opinion, Cities, for the nine years that he had been casting covetous glances at it, had done everything wrong. It made diversification decisions that always seemed to sour. It had all that acreage but wasn’t very good at finding oil and gas. Its stock was always undervalued. On Wall Street, Cities had a reputation as a plodder, but Pickens didn’t even give the company that much credit. He thought Cities was mismanaged, and he was not shy about saying so—especially in the presence of Wall Street analysts. The Cities management knew full well what Pickens thought of the company, and consequently their dislike of him went beyond pure business judgment. In the summer of 1981, at a time when Wall Street was full of rumors about a possible takeover of Cities Service, Charles J. Waidelich, the company’s chairman and chief executive officer, had told reporters that Cities was not interested in being bought; potential suitors, he had said, “should buzz off.” He didn’t mention any names, but everyone on Wall Street knew he was referring to Boone Pickens and Mesa Petroleum.

In fact, Pickens had made his first serious run at Cities that summer. First he bought up 4.1 million shares of Cities stock—5 per cent of the company—for $180 million. But he couldn’t hope to make a tender offer to go for 51 per cent; Mesa was simply too small to be able to borrow the billions of dollars that it would take. Instead, he came up with an unusual idea: he would make his tender offer with the help of partners—other oil companies that saw in Cities the cheap oil reserves that he saw. Tender offers are never done with partners, but Pickens had no choice. By early summer he had lined up two companies to go in with him: Freeport-McMoran and Louisiana Land & Exploration.

In mid-August, however, Cities found out about the partnership and began to play very rough. One of its investment bankers called Freeport and Louisiana Land and told them that if they didn’t back out, Cities would take them over. That was the end of Pickens’ partnership. Round one to Cities.

Round two began about a month later, when Pickens started looking for a new set of partners, convinced that the deal could still work. It was an arduous process, but by late this spring it was falling into place, and by the time Pickens got back to Texas from his trip to see the analysts in Boston, he had decided it was time to call a meeting. On the Wednesday after his return from the East, his lawyers and his financial people trooped downtown to Mesa’s Houston offices in the Dresser Tower to hear him try to take a group of bankers out of a little money. About $1 billion, to be precise.

To open the meeting, Pickens made a short statement, telling the bankers that he hoped to make a tender offer for Cities stock on June 1 and that he hoped they would keep the information they were about to hear confidential. Then the lawyers and financial people filled the bankers in on the details, such as they were: Mesa would raise $1 billion by selling to a group of partners either stock that Mesa would issue or, later, Cities oil reserves. (The bankers didn’t know it yet, but the partners were the Southland Corporation of Dallas, which owns the 7-Eleven chain; the Damson Oil Corporation of New York; the Madison fund, a New York investment firm; and the Sunshine Mining Company, a Dallas concern that runs a number of American silver mines.) The partners’ $1 billion would serve as collateral for $1.3 billion that the bankers would then lend to Mesa to complete the financing. With that much money, Mesa could offer $45 a share for 51 per cent of Cities stock—about $10 higher than the stock was bringing on the market.

As his associates talked, Pickens walked out of the conference room with one of his aides. He was pleased to see the deal coming together, but he was worried that it wouldn’t remain secret for much longer, because dignified forms of spying are a staple of takeover fights. He turned to the aide. “Look back there and tell me what you see,” he said.

“I see a roomful of people,” the aide replied.

“That’s right,” said Pickens. “And they all have one friend they can trust.”

First Strike

Friday, May 28, Tulsa

Pickens was right. Within days of his meeting with the bankers, word of it had leaked back to Cities Service’s headquarters in Tulsa. Now Cities realized it was in a battle for its life, and it began plotting its counterstrategy.

That strategy was unveiled two weeks later, and it was consummate hardball. On Friday, May 28, Cities issued a press release that read in its entirety:

Cities Service Company said it intends to commence a cash tender offer to purchase up to 51 per cent of the voting power of Mesa Petroleum Company at $17 a share. First Boston Corporation and Lehman Brothers Kuhn Loeb will act as dealer-managers [meaning Cities’ investment bankers] for the offer.

Cities had launched a preemptive strike, and a very clever one at that; for a targeted company to defend itself by going after its attacker was a brand-new strategy in the takeover game. Although there was some question in Pickens’ mind as to whether Cities really wanted Mesa or was just trying to scare him off, there was no question at all that it could swallow Mesa if it so desired. So the Cities offer was a real threat. In making the tender, Cities had shown unexpected life—it wasn’t the sort of thing plodding companies usually did. And Pickens, so wrapped up in pulling his partners together that he hadn’t spent much time thinking about what Cities was doing, had been caught completely by surprise.

The Bear Hug

Monday, May 31, Houston

To understand the dynamics of a corporate takeover fight, you need mainly to keep in mind one length of time: twenty business days. Under federal law, when a company makes a public tender offer for a block of another company’s stock, twenty business days must pass before the tendering company can actually purchase the stock. During that time, stockholders (meaning primarily the major portfolio managers on Wall Street, who control the fate of almost every major American corporation) who want to sell their shares “tender” them to the acquiring company. When the twenty days are over, the amount of stock the offer has attracted is announced and the acquiring company knows whether it has succeeded—that is, drawn 51 per cent of the target company’s stock—or failed. The waiting period is a frenetic, tense time: Wall Street comes alive with rumors, reporters scramble all over the story, and to the targeted company the twenty days seem like the grimmest of deadlines.

This, then, was the predicament Boone Pickens faced the day after Memorial Day: the Cities offer was about to begin, and the twenty-day clock would start counting down. Pickens did not yet have his partnership lined up, but even if he accomplished that within the next few days and made his own tender offer for Cities stock, Cities would still be in a position to buy Mesa before Mesa could buy Cities. That was an awful thought. It was imperative, Pickens and his advisers all agreed, that he do something, and do it quickly and publicly, if only to let Wall Street know that he was still in the game. The important thing was to keep the ball in the air until the Mesa team could get the partners in line and go forward with the attention to blocking the Cities offer. But what could they do now?

Pickens woke up early on Memorial Day in his Houston condominium, an opulent penthouse apartment on Buffalo Speedway. He began his day in typical Pickens fashion: he jogged several miles and then had a breakfast of cereal and fruit. All weekend long he and his advisers had grappled—unsuccessfully—with what to do about the Cities offer, and it was still very much on his mind. After breakfast he stepped into the shower, and that’s when it hit him. It was an utterly simple idea. “Why don’t we pull an ol’ bear-hug deal?” he thought. Within an hour, he was at Baker & Botts.

A bear hug is one of the oldest stratagems in the merger handbook; it’s a “friendly” offer that everyone knows isn’t friendly at all—a bit like Russia’s embrace of Poland. Unlike a tender offer, a bear hug is an offer made directly to the company’s board of directors (rather than to the stockholders) and is contingent upon the board’s approval. If the offer is high enough, sometimes a board will feel compelled to accept it, even when it doesn’t want to, because of its legal responsibility to act in the best interests of the company’s stockholders. That happens, but not often; most of the time a bear hug is simply a way of putting pressure on the board. It generates press coverage, it alerts the company’s stockholders that there is an offer out there, and usually it is a signal that there is another, less friendly move in the offing—like a tender offer at a lower price. Quite often, a bear hug is the inside fastball that sets up the curve on the outside corner.

Pickens had a little bit of all these purposes in mind when he conceived his bear hug. At the Baker & Botts offices, he laid out his idea to the assembled lawyers. What he wanted to do was call up Cities’ chairman and chief executive officer, Charles Waidelich, and offer to buy out his company for $50 a share. With Cities stock at about $35 a share, that was a 43 per cent premium. (In contrast, the Cities tender offer was only 25 cents higher than Mesa’s closing price of $16.75 on Friday, May 28.) Such a transaction would cost Mesa about $4 billion, half of which Pickens planned to pay in cash and half by issuing $2 billion worth of Mesa stock to Cities stockholders.

“Is there any reason we can’t do this?” Pickens asked.

None of the lawyers could think of any, so he next called his lead back, Continental Illinois, to confirm that he could get the $2 billion in cash he would need to do the deal. The bank said yes; friendly deals are always easier to finance than unfriendly tender offers because the acquiring company can borrow against the assets of the company it’s going to buy.

That taken care of, Pickens dialed Waidelich’s number in Tulsa. “Chuck,” he said, “I want to tell you about an idea we have.”

“I’m not interested,” said Waidelich.

Pickens persisted. “Wait a second, Chuck, I want you to at least hear me out. The offer is for $50 a share . . .”

“I’m still not interested,” replied Waidelich. “And it’s not a formal offer anyway. It’s not written down anywhere.”

“Hell, we’ll have an offer to you in Tulsa in three hours.”

“I don’t want it,” said Waidelich.

“We’ve got to bring it to you now,” said Pickens coyly. “We have a disclosure problem. Our stockholders need to know that we’ve made an offer.”

“But it’s not an offer,” insisted Waidelich.

“Aw, Chuck,” Pickens said, “you and I have been in business a long time and known each other a long time, and if we in this industry can’t call each other up and explain things like this to each other, then we’ve gone a long way in the wrong direction.” Then he added, “We’ll get you an offer in the morning, and we’ll have to put out an announcement, and I guess you’ll need to call your directors on this.”

“I have no intention of calling them,” replied Waidelich. “We’re not interested.”

But from Pickens’ point of view, it didn’t matter whether Waidelich was interested in the offer or not. The important thing was that the offer was on the table. Late that night, Mesa put out a press release announcing that it had made a $50-a-share offer to the Cities management, and the next day a Mesa lawyer arrived at Waidelich’s office with a letter from Pickens reiterating the offer. At last Mesa was in the play.

To the Mattresses

Tuesday, June 1, New York

On the 39th floor of the Waldorf Towers, the toniest section of one of New York’s toniest hotels, the Waldorf-Astoria, there is a large two-bedroom suite that is leased by the investment house of Lazard Freres. It’s a businessman’s suite, a place where a busy chief executive officer, in town on business, can rest his head by night and do his deal by day. The suite’s color scheme is simple and to the point: everything is done in shades of white. Its main room conveys not so much comfort as function. Half the room is a dining area, the other half a living area (sofa, coffee table, oversized chairs), and between the two, acting as a divider, stands a single wooden desk. There are two tall windows in the room, but the view they offer is one of the most forgettable in New York; only the Chrysler Building stands out to brighten the scene. Although the Waldorf is in the heart of Manhattan, the blandness of the walls and the blandness of the view combine to give the suite a little of the feel of a military bunker, a hideaway 39 stories high. Except for its seven telephones, the suite is cut off from the rest of the world.

This was Boone Pickens’ temporary headquarters in New York, the place where, as they say in the Mafia, he had gone to the mattresses. He had the suite thanks to the good graces of a Lazard partner, a fellow Texan named Jim Glanville (Pickens seems to have a good ol’ boy network that includes every Texan on Wall Street). Glanville told him to keep the suite “as long as necessary,” even though Lazard itself wasn’t in the deal.

It had been late Monday night when Pickens arrived in New York. He had come for two reasons. First, and most immediately, he wanted to keep the negotiations with his partners on track and to get them signed up and Mesa’s unfriendly tender offer readied within a few days. All he had so far was his friendly bear hug, which the Cities board was likely to turn down. He needed now to back that up with the tender offer—a much more serious threat to Cities because the management couldn’t control its outcome. To that end, Pickens had scheduled a Tuesday morning meeting in the New York office of George Gould, the president of the Madison Fund, which was tentatively in the deal for $200 million.

The other reason Pickens was in New York was that, quite simply, that’s where the play was. Texas might be where you could find oil and run a company, but only in New York could you do a deal like this. New York was where all the key players were; it was where you could hear all the rumors, and keep track of how “the Street” was reacting to your strategies, and be in constant touch with all the people on Wall Street who would be making decisions upon which your fate depended. Pickens knew that, and once he got to New York he also knew he wouldn’t be leaving anytime soon.

Pickens had brought an entourage with him. There was his special assistant, a former UT basketball player named John Bush, who had been brought in to man the phones in the suite. There was Robert Stillwell of Baker & Botts, who in 1964, as a cocky 27-year-old associate, had worked on the deal that created Mesa in the first place and had been doing legal work for Mesa ever since, becoming with time one of Pickens’ most trusted advisers. There was Jesse R. Lovejoy, called Bob, a young partner in the old-line New York law firm of Davis, Polk & Wardwell, who maintained a perfect pinstripes-and-suspenders Wall Street appearance while eagerly helping Davis, Polk to jump into the ungentlemanly merger field. There were two investment bankers from the firm of Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette: Joe L. Roby, a senior vice president, and Hamilton James, a tall, gangling 31-year-old Harvard Business School graduate who did merger work for the firm but had never been close to a deal this big before. There were, as well, perhaps a hundred other people who worked the Mesa side of the deal, most of them lawyers, but this was the core. If Pickens was the general in this play, then these men were his lieutenants.

For Pickens, there had been good news and bad news in the last few days. The good news was that his bear hug was having some effect on Cities Service. Waidelich might not have considered it a formal offer, but the reporters covering the deal had all treated it as such. Partly as a result of that coverage, there were, as Pickens had hoped, some large Cities Service stockholders—mostly Wall Street portfolio managers—who were calling the company’s management and directors to find out what they were going to do about the offer. Through the Wall Street grapevine, Pickens heard that the Cities board of directors was now planning a meeting early the following week to consider Mesa’s $50 bear hug. The Cities directors were starting to feel the heat.

The bad news, however, was of much more moment. It was, in fact, the worst setback imaginable: the collapse of his carefully built partnership. Pickens got the first inkling of disaster during his meeting with Gould on Tuesday morning. A phone call came in to Gould from an acquaintance of his, Henry Breck of Lehman Brothers. Along with First Boston, Lehman Brothers was advising Cities Service in the deal, and it didn’t take Gould long to discover that Breck was calling in that capacity. When Breck got on the phone he pointedly told Gould that if he stayed in the partnership with Pickens, “there would be a dirty fight and that Cities had adopted a scorched-earth policy” (as Mesa later contended in a court hearing).

So there they were again: the Cities scare tactics that had worked so well the previous summer. In the face of this threat, Gould did not back down. But the Southland Corporation, it turned out, had also received menacing phone calls from Lehman Brothers threatening a takeover attempt by Cities. And later on Tuesday morning Southland folded its hand.

Suddenly Pickens had lost a partner that had been expected to contribute $500 million to the deal. No lead partner meant no bankers and thus no money to make a tender offer. Last summer, after Cities had chased away Freeport-McMoran and Louisiana Land & Exploration, Pickens had been able to get the deal cranked up again at his own pace. Now he didn’t have that luxury. That morning the Cities offer had begun; the twenty-day clock was running. Although the Cities offer, at $17 a share, was very low (Mesa’s stock had risen higher than that on the stock exchange that day), there was no doubt that a lot of Wall Street professionals holding Mesa stock would tender it to Cities, on the assumption that Cities would eventually raise the offer. That’s the way Wall Street plays these deals. Under the timetable of the offer, Cities would be able to buy the Mesa stock tendered to it at 12:01 a.m. on June 28. On that date, if enough stock had been tendered, Cities would own Mesa Petroleum—unless Boone Pickens could pull a rabbit out of his hat.

The Home Folks

Wednesday, April 28, Amarillo

For the past three years, the Mesa Petroleum Company has held its annual meeting in late April in the gymnasium of the T. Boone Pickens, Jr., Fitness Center. The center is one of Pickens’ favorite things; he is a health buff, and he built it because he wanted everyone at Mesa to be as healthy as he is. Located on the third floor of the parking garage adjacent to Mesa’s modern headquarters in downtown Amarillo, the center has, besides the gym, a weight room, a jogging track, four racquetball courts (racquetball is Pickens’ favorite sport), carpeted locker rooms, and a small staff in charge of ministering to the health needs of Mesa employees and their families. It is a great fringe benefit, and to show their appreciation, Mesa employees commissioned a bronzed, life-size sculpture of their boss, which stands at the entrance to the fitness center. It depicts a muscular Pickens, racket in hand, crouched in position to smash a backhand.

At promptly 9:45 a.m. on the day of this year’s annual meeting, the creator of the T. Boone Pickens, Jr., Fitness Center walked past his statue on his way to the gym. He ambled down the hall with his hand stuffed in his pants pockets, but his eyes were alert and focused straight ahead, and his head was cocked in the direction of an aide who was whispering something to him. Pickens usually has an aide or two hovering nearby; that comes with the territory. For he is not only an oilman but also a member of that small and particular breed of American businessman, the chief executive officer. The schedule of everyone else at Mesa revolves around Pickens, and indeed his stamp is everywhere evident. Pickens dislikes large corporate bureaucracies, so Mesa gets by with only nine hundred employees. Pickens disapproves of interoffice romances, even when the two people are unmarried, so they almost never take place. Pickens hates smoking—he once fired the band at the company’s Christmas party because the bandleader refused to stop smoking—so it is rare to see a lighted cigarette in the Mesa building. As a chief executive officer, Pickens makes a lot of money ($892,129 in 1981), has homes in Palm Springs, Houston, and Amarillo and a ranch near Pampa, and lives a life relatively free of the little daily annoyances that the rest of us face. Perhaps in return, his life is an endless series of phone calls and meetings. This morning was no exception.

As Pickens made his way toward the gym, he stopped periodically to greet some of his local stockholders, many of whom were waiting n the corridor for a chance to say hello. This was a task Pickens handled with the skill and grace of a diplomat at an embassy reception, never lingering too long with one cluster of people but never giving anyone that brushed-off feeling either. As pleased as the stockholders were to see him, Pickens seemed equally pleased that so many of them had taken the time to come to his annual meeting. The decision to buy a stock is always to some degree an act of faith. In some fundamental way, Pickens is grateful to all the people who have shown enough faith in him to invest in Mesa—and he feels doubly grateful to the several hundred people in Amarillo who threw in their lot with him long before Wall Street had ever heard of T. Boone Pickens. Even now, he can usually remember how much stock they originally bought and how much that investment has appreciated. Mesa’s Amarillo stockholders are no longer very important to the survival and growth of the company, but Pickens still treats them as though they were.

When Pickens finally reached the entrance to the gymnasium, he took a quick glance at his watch. It was 9:55. “Ol’ Allan Cecil says that his meeting should last about forty-five minutes,” he mumbled, referring to Mesa’s chief public relations man. By ten o’clock Pickens, visibly anxious to begin, was standing at a podium that had been set up at the back of the gym. “Let’s get started here on time,” he said. Everybody sat down.

When Boone Pickens first started out, he couldn’t have foreseen that someday he would be chairing the annual meeting of a major exploration and production company. All he knew was that he wanted to break into the oil business and made some money at it. The year was 1955, and Pickens was 27 years old, just four years out of Oklahoma State University’s geology program. His father, though trained as a lawyer, had spent most of his adult life in the oil business. In 1944 he moved his wife and only son from Holdenville, Oklahoma, to Amarillo because he had taken a job as a landman for Phillips Petroleum.

By the time he graduated from college, Pickens had a wife and child to support, so when Phillips offered him a job as a geologist he took it. For four years he worked for Phillips, and although he was learning his trade, he was never content there, as his father had been. One day, during one of his increasingly frequent harangues directed at the incompetence of his supervisor, a Phillips district geologist, his wife, Lynn, said, “If you don’t like working for Phillips, why don’t you quit?”

She hadn’t meant it to be a serious remark, but the light bulb immediately switched on in Pickens’ head—and two days later he was either self-employed or unemployed, depending on which way you looked at it. He had $1300 in a Phillips thrift plan and, by then, two children.

With most of his savings Pickens bought a sturdy station wagon, which was probably the smartest investment a young man trying to get into the oil business could make; to get work, he had to spend most of his time on the road. Pickens would hear of a hot oil play in, say, Oklahoma, and off he would go to get whatever piece of the action he could find. He would do geological work. Or he would try to do small deals. Or he would do some well completion work. Sometimes he did all of those things at once. “I remember being up in Canadian, Texas, sitting on a well, and spending my time in a telephone booth trying to do some other deal,” he says. “It’s a hundred and ten degrees outside, and I’m about to get blown away in a windstorm, and all I can think about is that well ten miles away that I should be catching samples from.” You could make a living like this, but it was a scramble.

Within a year Pickens had gained a reputation as being both honest and talented. One of the men who was impressed with him was his wife’s uncle, a wealthy Amarillo businessman named John G. O’Brien. Together with another well-to-do Amarilloan, Eugene McCartt, the owner of a small grocery chain, O’Brien proposed to Pickens that they form a small oil company. This was exactly the break Pickens had been hoping for, and by September 1956 his first company, Petroleum Exploration, Inc. (PEI), had been formed.

Now he needed people who would invest in PEI, so he began knocking on the doors of businessmen in and around Amarillo who were known to do small-time drilling deals. He and a small staff put together one investor group after another, each with its own multiwell drilling program. As each group succeeded in avoiding too many dry holes, more people lined up to get into one of his investor groups. In 1959 Pickens took $35,000 and headed for Canada for the first time; good, cheap acreage was to be had there, and he formed a second company, called Altair, to get in on the play.

By 1964 both PEI and Altair had outgrown their original purpose. From 6 employees in 1956, the companies now had 26, and the drilling groups had multiplied to the point where three hundred outside investors owned four thousand separate properties in which the companies had an interest. Keeping track of their dealings had become impossibly complicated. To Pickens the obvious solution was to end the drilling groups and take the companies public. Looking back, it is obvious that going public was the right call; one man who put $80,000 in several PEI drilling groups says that today his investment is worth about $1.5 million. And John O’Brien’s original investment in 1956 has probably made him in the vicinity of $5 million. But it wasn’t so obvious then, particularly because investors who traded their interest for stock would lose the tax breaks that came with doing individual drilling deals. To persuade his investors to swap their drilling interests for stock, Pickens once again had to knock on doors. By May 1964 he had 239 investors signed up. That month PEI went out of business, replaced by a newly formed public company, Mesa Petroleum, and Altair became a wholly owned subsidiary of Mesa. Mesa issued 420,052 shares of stock to its new stockholders.

The subsequent history of Mesa is a success story of almost fairy-tale proportions. In the oil field Mesa seemed to make all the right moves. It got involved in North Sea exploration, discovered a major field, and then sold out at the optimal moment. In the early seventies, Mesa was one of the smallest companies to bid on federal offshore leases in the Gulf of Mexico; today Mesa has a $1.5 billion investment in the Gulf, and its Gulf Coast division is its largest revenue producer. On Wall Street, Pickens pulled off a coup in 1969, when Mesa took over the Hugoton Production Company, a company with fifteen times Mesa’s reserves. That deal instantly made Mesa a much larger company and made possible much of Mesa’s subsequent success. Three years later, Mesa bought a second company, Pubco, in Albuquerque, which became the foundation for its Rocky Mountain and Permian Basin divisions. In 1969 Mesa’s stock was accepted on the New York Stock Exchange, where it rose and then rose some more. Not everything Pickens touched turned to gold, to be sure: Mesa’s cattle division took a $20 million bath in 1974 when the bottom fell out of the cattle market. But even that had a silver lining; it taught Pickens that the oil business was what he was good at and what he should stick with. Never again did he try to diversify.

And as Mesa prospered, so did Pickens himself. At the time of the Hugoton deal, he was drawing a salary of $44,167 a year; a decade later it was over half a million dollars. He owns outright about a million shares of Mesa’s stock, worth on a good day about $20 million, and has as-yet-unexercised options worth about $120 million. He also has stock in the Mesa Royalty Trust and money invested in cattle. In 1980, after exercising one of his stock options, Pickens was named in several business magazines as the highest-paid executive in the country that year, taking down $7,866,000.

If there was a flaw in the Boone Pickens success story, it was probably at home. Pickens-watchers in Amarillo like to say that while he was building up Mesa, the one thing he had let suffer was his family. Pickens hates to hear that, because he doesn’t think it’s true—or at least he doesn’t think that any problems at home stemmed from his work schedule. ‘I never missed a graduation, or a recital, or any of the other things fathers are supposed to do,” he says in his own defense. When he wasn’t on the road, he had dinner every night with his wife and four children, even if he had to return to the office later. “As long as any of the children had something to say, we would talk,” he recalls now. “But as soon as they started some of that silly stuff, well, that wasn’t in the program.” Today, while he’s quite close to his two sons, one a young stockbroker in Houston and the other a student at SMU, he is distant from his two daughters, a fact that pains him.

In 1971 Boone and Lynn Pickens were divorced after 21 years of marriage, and the following year he remarried. His second wife, Beatrice Carr, was from Oklahoma; she and Boone knew each other as children, and for Pickens this was a much more compatible match. Bea Pickens loved being part of his world, and she was caught up in the excitement of watching Mesa grow. He could talk to her about Mesa. She liked to run the ranch. She had expensive tastes, but he was making a lot of money and could indulge her. At the time of the marriage, her youngest daughter was eleven years old. That daughter grew up adoring Boone Pickens, and she still does.

In 1974 Pickens built himself a little $2.5 million housing development. One of the houses there was for himself and his wife, and it was beautiful to behold. It was a spacious wood-and-stucco house, with glass panels along the main hall that went from floor to ceiling. Pickens’ favorite feature was the indoor tennis court, which was so well hidden that no visitor would ever guess it was there. The other eight houses in the development were built of the same materials, but they were much smaller. Pickens planned to sell them for $300,000 each, but for a long time they stayed empty. The word in Amarillo was that nobody wanted to live in a housing development where Boone Pickens’ house so clearly dominated the others. But finally he did sell the other houses, though for half the original asking price.

Back in the gymnasium on the morning of Mesa’s eighteenth annual meeting, Pickens was launching into a few closing remarks. After talking a little about the Mesa Royalty Trust, he turned to another topic dear to his heart. “We plan,” he said, “to take advantage of acquisition opportunities. There are only two ways a company like ours can grow: exploration or acquisition. Those are the only ways to expand the reserve base.” And then he opened the meeting to questions.

If Mesa had any disgruntled shareholders, they were not in evidence that morning. Only two stockholders took the floor, the second of whom rose to say, “Mr. Pickens, I’m a stockholder and I just want to applaud you and the company on the job you’ve done.” Everyone clapped at that, and Pickens replied, “Mr. Casey, we appreciate you coming here every year from Houston.” On that note, the meeting was brought to an end. Pickens stepped away from the podium and once again glanced at his watch before wading into the crowd. It was 10:45. Exactly.

A Dome Deal

Wednesday, June 2, New York, New York

It extremely important to Boone Pickens to be in control of events around him, but now events were in control of him. He had come to New York to take over Cities Service, but Cities seemed much closer to taking over Mesa. He had no partners, and thus no way of putting together a serious tender offer for Cities. The bear-hug offer was on the table, but how often did bear hugs work? Time was running out, too: on June 28 Cities’ waiting period would be over and it could buy Mesa. That would be the end of Boone Pickens and Mesa Petroleum.

At that desperate moment, Joseph Flom entered the picture. Flom, a lawyer, is one of the dominant figures in the small industry that has grown up on Wall Street around corporate mergers. He started doing takeover work a decade ago when most New York firms considered it unseemly. Today he is the most important partner in one of the fastest-growing law firms in the country: Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom. The merger in which Joe Flom is not working for one side or the other is rare indeed, and no matter how things turn out for the companies involved, they always turn out well for Flom. He has built his reputation up to the point where he does well even when there aren’t any mergers around, because companies keep him on retainer simply to prevent him from ever being on the other side of a deal they might do.

On Wednesday, the day after the partnership fell apart, Pickens and his entourage trooped over to Flom’s office and explained their predicament to him. Flom is a leprechaun—a short, white-haired, slightly stooped man whose pipe is never very far from his lips and whose expression is one of continual bemusement. He puffed on his pipe as he listened, asking questions but otherwise not saying very much. When they had finished, he looked up at Pickens and said, in a quiet voice, that yes, he did have an idea.

“Why don’t you do a Dome-Conoco deal?” he asked.

Of course! There were some embarrassed glances around the room—why hadn’t anybody thought of that before? What Flom had in mind was this: the Conoco-DuPont merger, which had dominated Wall Street the previous summer (and in which Flom had enlisted on Conoco’s side), had begun in earnest after a small Canadian company, Dome Petroleum, made a tender offer for 20 per cent of Conoco’s stock. Dome had no intention of taking over Conoco; all it wanted was enough shares so that it could swap that stock back to Conoco in return for a controlling interest of the American company’s Canadian subsidiary. However, instead of getting 20 per cent of the stock, Dome was deluged with stock—more than 50 per cent of Conoco’s shares ended up being tendered to Dome. That was a clear signal to Wall Street that dissatisfaction among Conoco stockholders was high and that the company was ripe for a takeover. Then several huge, acquisition-minded companies—most notably, Mobil and Seagram’s—jumped in with tender offers of their own, and the battle was on.

Flom thought that Mesa could do a variation on the Dome strategy. It could tender for whatever amount of Cities stock it could afford to buy without partners, say, 15 per cent. Then—and here was the variation—if a majority of the stock was tendered, Mesa would not back away as Dome had done. Rather, it would use the stock as a lure to attract enough new partners to be able to buy not 15 per cent but 51 per cent, and hence control, of Cities. Nobody had ever tried this before; from now on, the Pickens team would be flying without instruments.

The details were worked out: Mesa would make a tender offer for 15 per cent of Cities stock at a price of $45 a share. That was still about $10 a share higher than the stock was trading on the stock exchange. At $45 a share, 15 per cent of Cities would cost Mesa just under $600 million, and Pickens knew from previous discussions with his banks that this was probably the most he could borrow for a tender offer. The consortium of banks would still have to be lined up and the legal documents prepared, but everyone thought that could be done quickly. Before the meeting broke up, a launch date had been set. It was Monday, June 7, five days away.

A Night on the Town

Friday, June 4, New York

“This is supposed to be the best table in the house, you know.” Boone Pickens smiled when he said that, and so did the others who were with him, but it was true. They were seated front and center in New York’s fabled “21” club. If the Waldorf Towers is where the chief executive officers roost when in New York, then “21” is where they dine. It is not a great restaurant anymore (if it ever was), but its reputation remains oddly undiminished; it is still one of those places in New York frequented by well-to-do businessmen simply because other well-to-do businessmen go there. The food and service hardly seem to matter.

Pickens likes to go to “21” whenever he is in New York, but this was the first chance he’d had this time around. Most of his evenings since his arrival on Monday had been spent in strategy sessions, either in the Waldorf suite or in the legal conference room, and most of his meals had been eaten in haste. Tonight he was planning to relax a little and forget about the Cities Service deal for a few hours.

Just as his dinner was served, however, the deal intruded, in the form of a man from another table who walked over and introduced himself to Pickens. Pickens stood up to greet him while the others at the table, most of them lawyers working on the deal, continued eating. The man turned out to be an employee of Cities Service, and he was just drunk enough to say exactly what was on his mind. “I hope you beat the pants off them,” he told Pickens. “They’re a bunch of f―ing assholes. They don’t know what they’re doing. The best thing that could ever happen to Cities would be for you to get them.”

Pickens grimaced his way through this little diatribe, but when the man left, he happily recounted the conversation for the benefit of the others at the table who had missed it. “Boy,” he said, “it’s just amazing how much Cities is disliked.”

After dinner, the Pickens party walked the six blocks back to the Waldorf, where they bumped into Mesa’s vice president for finance, Gaines L. Godfrey, and several other Mesa financial people who were in New York to help get the bank consortium in place. The entire group, now numbering about ten, went into the Waldorf’s lounge for a nightcap.

“Well, how did it go today?” Pickens asked Godfrey, once they were settled in their seats.

“Pretty good. But we still haven’t gotten in touch with the people at Texas Commerce.”

“Gaad!” said Pickens with a laugh. (He is on the board of Texas Commerce Bancshares, so its inclusion in the deal was almost a foregone conclusion.)

“Gaines, did you hear about the letter we got today from Richard Ware at the Amarillo National Bank? He wrote us this letter saying he was behind us 100 per cent, and that if we needed any money, we could count on him for $5 million.”

Everybody smiled. “What we ought to do,” said someone else, “is tell him that we’ve raised $995 million and his $5 million will put us over the top.”

The smiles turned to chuckles. “It’s pretty nice of him just the same,” said Pickens.

A Day at the Races

Saturday, June 5, New York

Alan Habacht sat down at the table, put his napkin in his lap, looked up at Pickens, and said eagerly, “I want to hear everything that’s happened so far. From the beginning.” Pickens smiled. It was one o’clock Saturday afternoon, and Habacht had come by the suite to have lunch.

Habacht, Pickens’ friend, is the analyst with Weiss, Peck & Greer. He has watched Mesa for a decade, and wherever he has worked, his firm has had Mesa stock in its portfolio, in no small part because of Habacht’s faith in Pickens. Habacht sticks with Pickens because Mesa has made him money in the past and he expects Mesa will make him money again.

Habacht suggested the lunch partly to get the story of the deal from the horse’s mouth and partly to offer his support. But as both men knew, what Pickens needed most from Habacht—that he keep Weiss, Peck & Greer’s Mesa stock away from Cities Service’s tender offer—was simply not possible. That would conflict with the firm’s duty to the people who had entrusted their money to it. Assuming (as everyone on Wall Street did) that Cities would raise its offer, Habacht needed to have tendered his stock in order to reap the maximum gain. During lunch, Habacht spelled out his dilemma in a mildly apologetic voice, but Pickens brushed it off. “I know you have to tender your stock, Alan,” he said. “That’s the smart play.”

As they ate the soup and sandwiches sent up by the hotel’s room service, Pickens regaled Habacht with the story of the deal so far, going over the convoluted plot in great, laborious detail. Then, with Habacht up-to-date, the two men retired to the more comfortable living area of the suite. Pickens picked up a copy of the Cities annual report from the coffee table. He flipped to the back page, where the company’s board of directors was listed, and went down the list one by one, trying to guess how each director would vote on the Mesa bear-hug offer at the Cities board meeting, which was now three days away.

This had become Pickens’ favorite game in the past few days because he was convinced that the board was going to call him in to begin negotiations. Every one of his advisers thought there wasn’t a prayer of this happening, and Joe Roby had bet him $200 on the outcome of the board meeting.

Habacht looked down the list of directors. “You’ve got ten outside directors and three inside. That’s thirteen altogether,” he said. “The three inside you can forget about, so that means you need seven out of the ten to win. I don’t think it’s there. Where do you see it?”

“I’ll tell you what’s going to happen,” said Pickens. “One of the guys on the board who owns a lot of that stock is going to say, ‘You fellas are sitting here with no interest. I’m sitting here with a million and a half shares. Those shares were worth $68 and now they’re worth $38’—see how convincing this speech is, Alan—‘and it’s not even a comfortable $38. That little ol’ company is holding the price of our stock up.’” Pickens believed—probably correctly—that the only reason Cities stock had not dropped below $30 a share was that Wall Street expected Mesa to make some kind of run at Cities.

“ ‘So what I’ve really got,’ ” said Pickens, finishing his Cities director’s speech, “‘is a $68 to a $38 to an $18 if Mesa is out of this play. Now I’m 50 points down—that’s a $75 million hit—and I’m not liking it. And that’s where I’m headed if you guys sit here today and tell me we’re not going to consider a $50 offer.’ Your turn, Alan.”

Habacht laughed. “I’m not going to get into this with you because I’ll lose,” he said. “But I’ll tell you this: I’ve been around long enough to learn that they are going to find a way to turn you down. You can’t possibly expect to win this thing at the board level. Am I wrong?”

“You’re wrong,” said Pickens. “Yes.”

Habacht chewed that over for a minute and then changed the subject. “Is there any way they can get you?” he asked.

“Oh, yeah, I guess,” replied Pickens. “But you can’t worry about that. We can always get a white knight if we have to.”

“White knight” is Wall Street jargon for a company that comes into a deal at the behest of the company under attack and makes a higher bid for it. The target company still ends up being taken over, but by someone it considers friendly to its interests—and to its management.

“Is the white knight there?” asked Habacht.

“No. I haven’t worked on a white knight,” replied Pickens. “Between you and me—and don’t repeat this—the only way they are going to beat us is if they find a white knight themselves.”

As Habacht was rising to leave, he and Pickens got to talking about the Belmont Stakes, which would be running in a few hours, and Pickens was reminded that a friend of his had a horse in the race. He pulled from his pocket a small roll of bills and peeled off a $100 bill. “Put that on Estoril for me, Alan. The guy who owns this horse says it’s the best horse in the race. He was real excited—said he was going to win the thing going away.” Habacht took the bill and left. Estoril came in seventh.

The 10 Per Cent Solution

Monday, June 7, New York

The Mesa tender offer—for 15 per cent of Cities Serivce’s stock at $45 a share—was launched on Monday morning, right on schedule. The bank consortium was lined up; the documents were readied and flown to Washington, where they were filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission; and the reporters covering the deal had all received phone calls on Sunday night from Pickens in which he had briefed them on his latest move. By the time the New York Stock Exchange opened at nine o’clock, everyone on Wall Street knew that Boone Pickens was doing a Dome deal and Cities’ stockholders had twenty days to tender their shares to Mesa. The clock was ticking.

With the market open, the first question for the people in suite 39-F of the Waldorf Towers was how was Wall Street reacting to the Mesa tender offer? At ten-thirty the first answer came in. Cities stock was at 36 7/8, down 1 1/8 from where it had closed on Friday. A bad sign. If Wall Street had thought Mesa was going to succeed in swallowing Cities, the professionals would have begun buying Cities stock, intending to sell it to Mesa (because holders of an acquired company’s stock always make a fat profit by selling to the new owner), and the price would have jumped instead of fallen. To find out why that wasn’t happening, Bob Lovejoy went into one of the bedrooms and called several Wall Street arbitrageurs.

All the large investment houses have arbitrage departments, which make their money by betting on the outcome of a merger. Arbitrageurs—or arbs, as they are called on Wall Street—buy stock at the market price in the company they expect to lose the battle and tender it to the expected winner at the takeover price, which is always above market. In a small merger fight, the arb community sometimes controls so much stock that it can decide the outcome. The Mesa-Cities deal was far too big for that, but the arbs were still worth talking to, partly because they were the chief conduit of Wall Street rumors and partly because everyone else on Wall Street would be influenced by what the arbs were doing.

Lovejoy emerged a few moments later with his report. “Barry Allardice at Morgan Stanley says this was the perfect play for us, the best move we could have made right now. All the arbs think we’ll get over 50 per cent of their stock.” The problem, Lovejoy continued, was that although the arbs might admire Mesa’s move, they still saw Cities as being out in front. The reason was the time difference: the expiration date on the Cities tender offer for Mesa was Monday, June 28; for the Mesa tender offer for Cities, it was Friday, July 2. Thus even if each side were to get 51 per cent of the other’s stock, Cities would be in front because it could take over Mesa four days before Mesa could take it over. Although Mesa had finally launched its tender offer, it still had one more mountain to climb. It now had to find a way to eliminate Cities’ time advantage; otherwise everything it had done up to this point would be for naught. For the people in the suite, that was the new priority.

The suite was filling up now, as it typically did late in the morning. The earliest arrivals were Lovejoy and Bush, who had breakfast with Pickens. Lovejoy had been up all night Sunday overseeing the preparation of the offering documents. But he still looked fresh and alert, and when he came in for breakfast he brought a bag of Granny Smith apples, which Pickens loves. Bush was now sitting at the desk, handling a blitz of phone calls coming in on the two phones there. Stillwell, who had just awakened, was sipping coffee at the table. Bea Pickens made her first appearance of the day before heading off for lunch with a friend; she had flown in from Texas over the weekend. Sitting on the sofa was a rumpled man named Richard Cheney. He was another charter member of Wall Street’s merger industry, vice chairman of the public relations firm of Hill and Knowlton who specialized in “takeover and proxy fight PR” and had recently been brought into the deal by Pickens. Others on the Mesa team also wandered in and out of the room during the morning: Gaines Godfrey and his people, who were working out of a second suite in the Waldorf, and various and sundry lawyers who were working under Lovejoy and Stillwell.

Although objectively nothing of significance was happening, you could sense that the people in the suite were getting wound up. The doorbell rang frequently; most of the time it was the bellhop delivering envelopes for Pickens. Some of them contained telegrams of support from friends; others, wire service clips compiled by Hill and Knowlton; and still others, résumés from job seekers. The people in the suite paced around the room, changed seats, talked in small snippets of conversation, and, most of all, talked on the telephone. In the three weeks Pickens spent in New York, the ringing of the telephone was the sound he heard most often, and in some ways it was the most reassuring. The constant phone calls—from reporters, from Wall Street investment bankers passing along rumors, from stockholders, from his own office—gave Pickens, and everyone else in the room, the sense that suite 39-F was at the very center of the universe. During the time Pickens was there, Menachem Begin arrived in New York to address the United Nations and stayed in the Waldorf Towers. Also, 500,000 people from all over the country demonstrated in New York’s Central Park against nuclear power. Pickens, completely absorbed by his own deal, scarcely noticed either event.

Around three o’clock, just after a speaker phone had been delivered to the suite, courtesy of Lovejoy, Pickens got a call from one of Mesa’s investment bankers. Somebody turned on the speaker so everyone could listen.

“Oxy [Occidental Petroleum Company, the nation’s twelfth-largest oil company] had a meeting with analysts today,” the man reported. “There were about two hundred people there and the only thing they wanted to talk about was Mesa-Cities. There was a lot of enthusiasm. A couple of people said that our tender really put the pressure on Cities to raise the price of their offer.” (At $17, Cities’ offer was now nearly $2 below Mesa’s market price.)

Now he turned to more serious business. “I talked to Bob Abboud. [A. Robert Abboud is the president of Occidental Petroleum.] He said, ‘All of us would like to be involved, but the Doctor’ ”—meaning Dr. Armand Hammer, Occidental’s octogenarian chairman—“ ‘is worried about an unfriendly deal.’ The way to do this is to get Flom to talk to the Doctor. You have to have the Doctor understand how this is different from an unfriendly deal if 51 per cent of their stock is tendered to us. [What this meant was that if a majority of the stockholders favored the transaction, the deal would not necessarily be considered unfriendly.] Flom has a long-standing relationship with the Doctor, so he’s the one to do it. Anyway, Boone, I think there’s a live interest here.”

“Great,” said Pickens. “I think this deal will be easy to sell if you’ve got 51 per cent in your pocket.”

“Right. But we still need to get Flom to sprinkle his holy water on it. And also, Boone, Abboud said if you’re in a defensive mode and you need a white knight, they respect you and would be interested in being your white knight.”

To this last remark, Pickens made no reply.

Pickens had planned a late-afternoon strategy session, and by five o’clock all the key strategists except Flom—who had a dinner engagement elsewhere—had assembled in the suite. Cities stock had closed at 36 ¼, down 1 ¾ from the opening price. The trading volume in Cities had been extraordinarily light for a company that had just been hit with a tender offer 25 per cent above its market price.

Pickens slumped into one of the oversized chairs. He looked tired and discouraged. “Except for the papers this morning,” he muttered, “this has been a zero day.”

Everyone sat down around the coffee table. “I don’t know what to say,” Pickens said. “I thought we would be getting our presentation ready for the Cities board at this point.”

Before he could go on, he was interrupted by a phone call. It was from a large Cities Service stockholder. Because of his holding, he could get through to some Cities directors, but he was unhappy with Cities’ management, and for that reason, every time he had a conversation with someone at Cities, he immediately leaked what he had been told to Pickens. He was one of Pickens’ main sources of intelligence in the deal; no doubt Cities had sources doing the same for it.

“He says he talked to Waidelich,” said Pickens after hanging up the phone. “He said, ‘I’ve got an awful lot of stock and I’m worried. What are you going to do at the meeting tomorrow?’ Waidelich told him to hold on to his stock, because there would be no surprises at the board meeting. He complimented Chuck, said he was absolutely cool and rational. There wasn’t any panic in his voice at all.”

“You know,” said Lovejoy, “they could delay this thing for a month. They could say it’s too complicated, it needs further study. That would be the smartest thing they could do.”

The phone rang again, and Pickens walked over to the desk to take the call. Two of his own employees were calling in from Tulsa. On Pickens’ instructions, they had gone there to see what they could glean from hanging around Cities’ hometown. Pickens turned on the speaker.

“How did you do?” he asked.

“Well, we got into the Cities building today,” one of them replied. “We applied for jobs. They wouldn’t take our applications, Mr. Pickens.”

Everyone chuckled at that.

“We had lunch in the Cities cafeteria. Boy, people sure are taking your name in vain around here.”

“So if we get a house in Tulsa, you would advise that we get one with a big fence?” said Pickens.

“That’s about right, Mr. Pickens.”

While Pickens was taking a third call, Hamilton James, of Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette, the 31-year-old investment banker for whom these weeks in the Pickens suite had meant working on the biggest deal of his life, proposed to the others a new idea that he thought might finally turn the tide in Mesa’s favor. If they agreed with him, this would be a major strategic contribution to the deal. He leaned forward and blurted out his idea.

“We need to get the date of their tender offer extended past ours,” he said. On this point, everyone was agreed: as long as Cities had that four-day time difference, it was still in the driver’s seat. “We have to get in a position where we can buy their stock first. That puts the monkey on their backs instead of ours.”

The way to accomplish this, James thought, was to find someone friendly to Mesa to make a competing tender offer for Mesa stock. The law says that any time there is a competing tender offer, ten days must be added to the timetable of the first tender offer. The loophole that James saw in the law was that there was nothing in the rules that said how much stock the tender offer had to be for. Thus James’ scenario would work like this: someone would make a competing tender offer, but for only 10 per cent of Mesa’s stock. That would force Cities to wait an additional ten business days before it could begin to buy any Mesa stock. In the meantime, Mesa would put together its deal to buy a controlling interest in Cities. When July 2 rolled around, it would buy the Cities stock . . . and Cities would then become a subsidiary of Mesa Petroleum. Naturally, the new parent company would put a quick end to Cities’ tender offer for it.

“It has to be a real tender offer,” said Lovejoy. “They would have to come in because they thought it would be a good investment. Boone couldn’t promise anything because then it would be a self-tender and the other side would go to court and say it didn’t count.”

But that was a minor quibble; the Mesa strategists, including Pickens (who had returned to the sofa), all thought that James was onto something.

“Ten per cent of Mesa wouldn’t be much,” said Pickens. “About $140 million.”

“I think you should figure a bit higher than that,” answered Lovejoy. “More like $150 million to $170 million.”

Clearly they would move ahead with James’ plan. But it seemed somehow not to interest Pickens fully. “You know,” he said, “I still don’t think that board is going to turn us down tomorrow.”

Ulysses, Kansas

Tuesday, June 8, New York

Pickens was wrong and Joe Roby $200 richer. Late Tuesday afternoon, Cities Service announced that its board of directors had unanimously rejected Mesa’s $50 bear hug and recommended that Cities stockholders do likewise to Mesa’s $45 unfriendly tender offer. To underscore the announcement, Cities’ chief executive officer, Charles Waidelich, met, for the only time in this deal, with a selected assemblage of merger reporters in the conference room of Cities’ Park Avenue offices. He stood at a podium at the back of the room and read from a prepared statement. A civil engineer who had spent thirty years rising through the ranks at Cities, he looked tense and uncomfortable; his jaw was clenched, and beads of sweat were forming on his forehead. His voice was a little jumpy, but there was no mistaking the message: “The Cities Service boards of directors is unanimous in its view that the board and not Boone Pickens will make the decision as to whether, when, and upon what terms Cities Service is for sale.”

Having taken his little dig at Pickens, Waidelich then threw a new twist into the plot. The Cities board, he announced, had a new proposal—its own bear hug for Mesa. As Waidelich explained it to the reporters, Cities was offering to pay $21 a share for Mesa stock, contingent on the approval of the board of directors of Mesa Petroleum.

No one from Mesa was allowed into Cities’ offices to attend the press conference, but somehow Richard Cheney, the PR man, managed to get a tape recording of the conference. Fifteen minutes after it was over, Cheney, Pickens, Bea Pickens, and the half-dozen others in the Mesa command post were listening to Waidelich on tape—and truth to tell, they were enjoying every minute of it. The reporters browbeat Waidelich, and he simply lacked the skill to deflect their questions gracefully. No, Waidelich said in response to one question, Cities had never, ever threatened to tender for any potential Mesa partner. “I just told them that I looked at their company and they appeared to be very attractive,” he said.

“That’s the same thing, Mr. Waidelich!” bellowed Robert Cole of the New York Times.

Cheney found that exchange so amusing that he replayed it anytime someone new came into the suite.

At another point on the tape, Waidelich said he hoped Pickens would stay on if Cities bought Mesa—“I think Mr. Pickens could make a contribution” were the exact words he used—but his voice was so lacking in conviction that you could hear several reporters snicker.

Pickens barely had time to listen to Waidelich’s statement before the phones began ringing; reporters wanted his reaction to the latest Cities move. With the tape recorder still playing on the coffee table, Pickens moved to the desk to be closer to the phones. The first call he took was from Robert Cole, a gravel-voiced, overbearing man who had been Waidelich’s chief antagonist at the press conference.

“How do you analyze the offer, Mr. Pickens?” asked Cole.

“Well,” said Pickens, collecting his thoughts as he spoke, “the $21 is not much of an offer, that would be my feeling.”

“How would you feel about staying with Mesa if Cities took it over?”

Pickens paused for a second and then grinned. “I would suppose that if Cities took Mesa over, then Chuck would offer me a job as Southwest Kansas district geologist, based out of Ulysses.”

Cole chuckled and wrote down the line. “Southwest . . . Kansas . . . district . . .”

“Southwest Kansas district geologist, based out of Ulysses,” repeated Pickens. “Did you get that, Bob? You can quote me on that.”

To Pickens the underlying message of the Cities offer was clear. Any illusions he had harbored about the Cities board’s caving in were dashed. It wasn’t going to happen. If he wanted to win this fight, he was going to have to go the route he and his strategists had outlined that night in Joe Flom’s office. First, he would have to get the stockholders of Cities Services to tender as much of their stock to Mesa as possible. Then he would have to round up a new set of partners to help him buy that stock. He already owned 5 per cent of Cities. His banks had lent him $600 million to acquire the 15 per cent for which he had officially tendered. Assuming that his offer attracted over 45 per cent of Cities (an assumption Pickens always made), that meant he still had to find the money to buy another 31 per cent of the stock at $45 a share. That would cost $1.1 billion, which he had to come up with in two weeks. The search for partners was on. Just as he had done 25 years before in Amarillo, the time had come again to begin knocking on doors.

Before rejoining the others, who were still playing and replaying the tape of Waidelich’s press conference, Pickens took a call from another reporter, Tim Metz of the Wall Street Journal.

“Tim,” said Pickens, “did you hear ol’ Waidelich say there would be a job for me if Cities took us over?”

“I wasn’t there, Boone, but I heard about that,” said Metz.

“You know what the job is? He’s going to offer me the position of Southwest district geologist, based in Ulysses.” Metz laughed. “You can quote me on that, Tim.”

“Do you think this offer shows a weakness in their position?” Metz asked.

“I think what it shows is a weakness in their intelligence,” replied Pickens. Metz jotted down that last quote and hung up.

Pickens turned to the others in the room. “That was a tough thing to say, but I guess it’s time to come out swinging.”

“This Is a Sweet Deal”

Friday, June 11, New York

Every day he was in New York, far away from the T. Boone Pickens, Jr., Fitness Center or the YMCA in Houston, where he plays racquetball, Boone Pickens tried to find some time for running. It wasn’t racquetball, but at least it was exercise. He would usually rise at six o’clock, run several miles along the periphery of Central Park, and then return to the suite in time for a working breakfast with Lovejoy, Stillwell, and a few of the other Mesa strategists.

On this Friday morning, breakfast was over and Pickens, Stillwell, Lovejoy, and Gaines Godfrey were all sitting around the coffee table, chatting about nothing of any great importance. The Journal and the Times were stacked on a corner of the table, and the latest batch of Granny Smith apples was piled high in a bowl.

The others were all stressed in suits, but Pickens has yet to get out of his post-running clothes—a monogrammed white bathrobe and slippers. That casual attire, along with his generally relaxed air, made him seem more like a character on Love Boat than a man in search of $1 billion. But he had been deep into it for three days now. Around nine-thirty the group broke up. Pickens took a shower, got into a business suit, and headed downstairs to the other Waldorf suite Mesa was using, where he was scheduled to meet with a potential partner.

It was while he was attending this meeting that the bad news came over the Dow Jones wire: the Cities Service offer had drawn 45 per cent of Mesa’s stock in a proration pool. In every merger fight, the proration date is a kind of preliminary deadline that gives each side some idea of who is ahead so far. A creation of federal securities law, it comes ten days from the start of the tender offer, and the stock that is tendered in time to make the proration pool gets certain advantages over stock that comes in later. For that reason, Wall Street professionals always tender their stock in the proration pool if they are going to tender at all, and thus on the date the pool closes, a fair indication can be gleaned as to which way Wall Street is playing the deal. Pickens had hoped the number would be a lot lower than it was; some analysts had been telling him that it might be as low as 25 or 30 per cent of the stock. Now he had to face the fact that if Cities raised its offer—and everyone on Wall Street assumed it would; that’s why they had jumped into the pool in the first place—it would surely attract another 5 per cent of Mesa, and maybe a lot more. Cities still had the four-day time advantage; it still had the financial advantage of being able easily to afford to buy the Mesa stock it got. And now there was no doubt that Cities was going to get enough stock to buy Mesa. It was still ahead in this game.