This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

If only the old man had looked up at me and gasped, “Sell,” wouldn’t things be different today? He died on November 26, 1981, when oil was selling at $31 a barrel. He had a small, independent oil company in San Angelo, but we never thought of ourselves as rich. My dad, John H. McCammon, hated ostentation and was secretive to boot, so we didn’t really know how much money there was until the will was read. Oil had hovered around $3 a barrel during my childhood. And since none of us had been involved in the family business in 1973, when prices shot up as OPEC took over production quotas, we had no inkling how much our fortunes would rise when the Old Man died.

We gathered around a long table in a San Angelo bank for the reading of the will. Mother, chic as always with her cloche hat, sunglasses, and cigarette, was the sad but bemused widow as the words were read. Baby Brother patted Mother’s arm, and my two sisters were attentive. I had been told years ago that I would be the executor, but I had no idea what that would entail. In an aside to me, the accountant said, “I wish Mac had waited until after year-end, for the new tax law to go into effect.”

The will was wonderful, pure Mac. The Old Man had written it himself. He left the pickup to “his paprikash” (his nickname for Mother), knowing that she hated driving it. He didn’t leave anything to one nephew, writing, “John has enough.” There were lots of references to the state of the industry and his fear that the oil business will become nationalized. He gave instructions that the business should be sold if the kids didn’t agree. How well he knew us.

I had always gotten along fairly well with the siblings. As the oldest, I had been the family mediator, which was why the Old Man named me executor. But as soon as the will was read—as soon as we walked out—I felt my relationship with them change. We were so different, with separate lives and values. About the only thing we had in common was that each of us was highly opinionated. Now the family business was forcing us back together. One sister had worked in merchandising, and the other sister and I had been in public relations. Baby Brother was the one who had grown up in the oil patch, next to Dad, working on wells, pump jacks, and work overs; checking gauges; hauling stuff; almost dying once inside a tank that they were trying to clean out. It was only natural that he resented my being named the executor. Having worked in the business for years, he knew things I couldn’t have known. And he is smart. He knows how to crunch numbers. But I didn’t always trust his judgment.

I was smart enough to know that there was a lot I didn’t know. So first, I shopped for a lawyer. The Old Man hated lawyers, calling them, like bankers, “creamers.” He hated insurance men too, but he saved his real wrath for bankers and lawyers. I think it was because they don’t do physical work. After much asking, I settled on a firm in Midland, thinking that since I lived in Dallas and Brother lived in San Angelo, Midland was a good compromise. I also hired a tax lawyer to help sort out the estate. He became my guardian angel, not only providing expert tax advice but also keeping me sane by standing by, guiding me, most times being the only person who was not angry with me for one reason or the other. Working with the lawyer and the accountant, who had been with Dad for years, I began the business of running an estate, trying to keep siblings happy, and learning about a volatile and exciting business.

Ooh, and the money. The figures looked good. The family would sit in the office in San Angelo, sort of like we had in church. We would pore over trial balances and Railroad Commission reports. We would see where the money was coming from, how much oil was sold from each of the wells, and how much was being spent on each of them. We would learn how much water had to be hauled from the wells that collected salt water so that the ranchers’ precious water supply would not be contaminated. Cows that had wandered into a pit had to be paid for, bringing much more than they would have at auction. Here we were after all these years, still an unruly group of children, no longer quarreling over who gets the drumstick but over more difficult questions: Do we drill? Do we say yes on the very expensive water-flood project?

From the start, I could feel Brother chomping at the bit to drill. “Drill, goddammit, we’ve got to drill,” he would holler at me as though I were a deaf person or a foreigner, or the way people do when they think hollering will change your mind. For four years he pushed me to expand, expand, expand. He changed the locks when he was angry at me, or he forgot to take me to the airport because he was busy doing “bidness, goddammit.”

My sisters weren’t happy either. They wanted to know what the hell I was going to do and how soon I was going to do it. Couldn’t we get more cash out? After all, it was “ours” now. Yet they were infuriated when I sold the Texas Eastern stock the Old Man had bought. Emotionally, we all had our own ties to the past, the Old Man’s way of doing things, and our newly perceived vision of how it should be.

We did drill. Well, only twice, but each well cost $250,000. Brother would exhort us to drill more, like Jimmy Swaggart saying “Have faith.” But seeing the five frac tanks, the big red monsters lined up around the wells, put me into shock. It was all so expensive. Brother and his engineer thought it made sense to drill through several zones at once, maximizing the payoff as well as the risk. Maybe trying to perforate that many zones was ambitious, I worried. Then there was the headache of updating our company records, most of which had been filed in the Old Man’s head—deeds, deals, when a well was fraced, how much casing had been used, where the pipe he had bought on sale in Coleman was being stored. Finally our accountant, in his usual laconic manner, said, “Hell, let’s write it off,” then laughed in a slow, rumbling way because business was good, real good. It was hard to worry too much.

I started reading the Wall Street Journal and going to the seminars in its advertisements. I listened to the experts, from foreign policy types who lectured on OPEC to oil people pointing at charts that looked so good with the numbers going up, up up. The money boys would shout “Fifty dollars a barrel,” using elaborate charts, slides, and “testimony” to show how the future was to be. The mood reminded me of a religious revival. “Do you feel the spirit?” The men at the seminars seemed so smart. How could they be wrong? Still, I was skeptical. Not because of any foresight or shrewd judgment but simply because it was all so new to me.

I loved my educational process at these seminars. In the overwhelmingly male atmosphere I felt like a woman in a Moslem country. I enjoyed my new role as an oil heiress, but sometimes all that power made me uneasy. The men would query me: How many wells? Where are you all? Oh, really? maybe you’d be interested in some deals; here’s my card.”

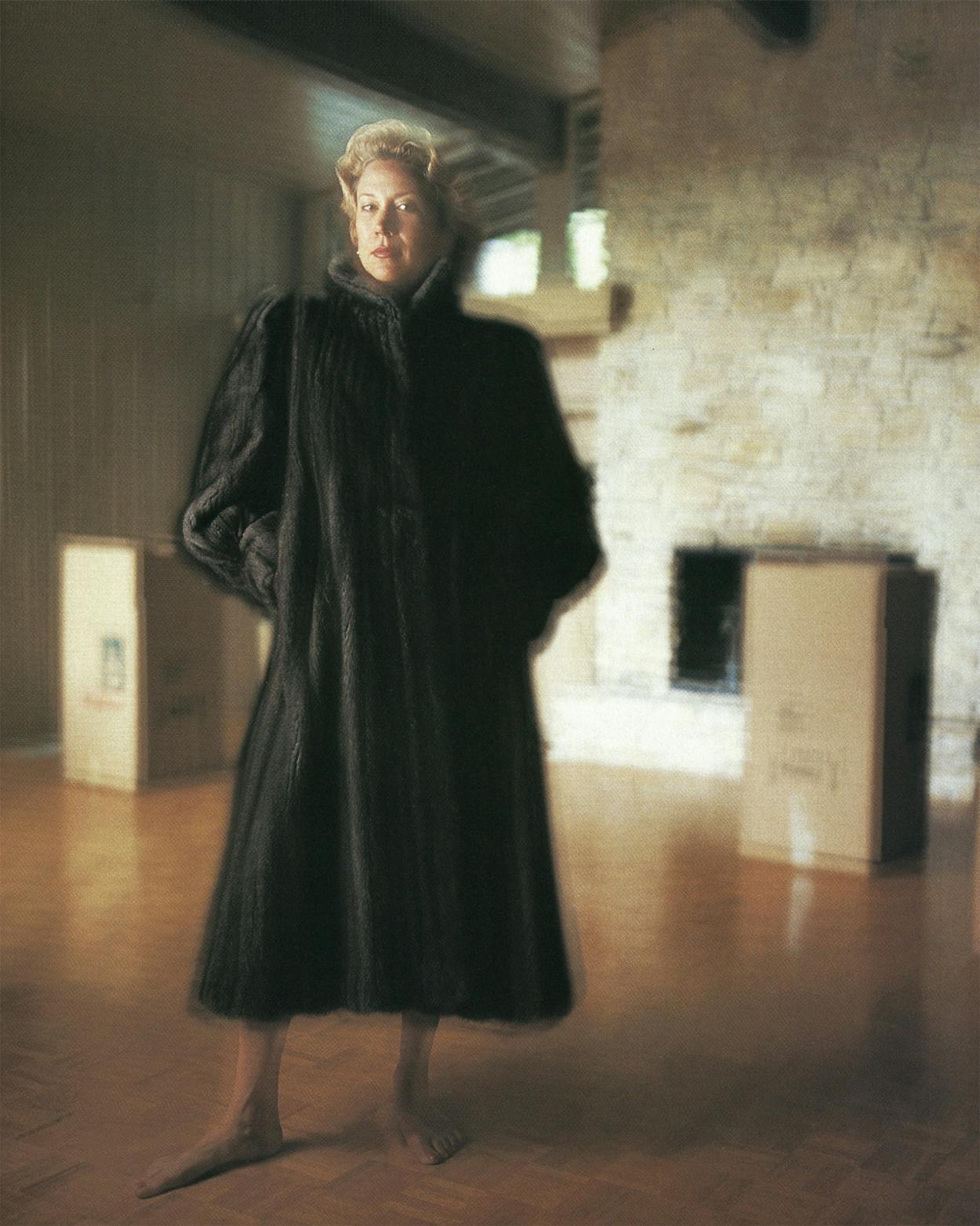

And after the seminars in Dallas and Houston, I would go shopping. I can remember, in the passion of the day—when oil was up—going to Neiman-Marcus in Dallas. Feeling like a Gould or a Rockefeller in my own way, I walked in and casually strolled about until, like a woman possessed, I found myself in the fur salon. The luxurious long and full coat was on me, its collar high around my hair and neck, its sleeves beautifully tailored to gather tightly around my wrists, its $10,000 price tag daring me to take the coat home. The next thing I knew, I had spent in half an hour what I used to make in three months. I was not shocked. What was $10,000 next to what it cost to drill a well? My sense of financial scale had expanded overnight. I was pleased in that foolish way you rationalize buying something that you can afford but don’t need.

I bought a leather sofa quickly one afternoon before a party, thinking, “Well, it will last forever.” I used to take forever to buy things. My feeling of never having enough money had always triumphed over my mother’s voice—one that had been through depression and war and that said, “Get it, get it.” Once I had the inheritance, I realized how much of my mother was in me. The Old Man hadn’t been able to enjoy his fortune. He had driven around in his old pickup and work clothes and had loved it when people mistook him for Mr. McCammon’s pumper. I remember that he had been disgusted by how much I’d paid for a jar of preserves or asparagus. “I don’t see how you can enjoy it,” he would say to me.

Having been raised so conservatively, I was ready to spend my newfound wealth. So I easily bought clothes, perfume, diamond earrings, new issues in the stock market, and lots of panty hose. But I hated contributing to my Keogh plan, knowing I couldn’t get the money out until I was “of a certain age” that seemed to me as distant and remote as my youth. It was more exciting to swoop into stores and not really look at the prices, to go on trips, and to go out to eat, blowing $500 on dinner at Calluaud’s. Skiing in Vail or Aspen, sending my son to summer school in California when he flunked English or to Outward Bound in Maine were things that cost a lot but that I liked to do. So was sending him to St. Stephen’s Episcopal School in Austin, knowing the pleasure I would feel when I was asked where my son went to school. Still, standing around at a soccer game or a Parent’s Day, I’d meet parents who I knew had always gone to private school and had always had money, who probably suspected that I was still paying for my Christofle silver from Gump’s on the monthly plan. One evening, I’d had too much wine and argued over the price of one of the bottles that had been easily ordered. I wasn’t really gauche, just having a good time.

Hell, yes, I had a great time making my Gold Card sweat. Afterwards, I would return to San Angelo, where the family would scrupulously go over the balances, arguing more and more over where and how the money was spent.

All along, my hidden fear was that this was a fluke, like winning a contest. After all, I had worked for a living; I had struggled. I knew how hard it was, as the Old Man used to say, to rub two nickels together. And in retrospect, I don’t think any of us had our heads in the sand. We suspected that the price of oil might start heading down. We were just enjoying the good life while we could. But by the end of ’84, the papers were full of bad news. You could go out to West Texas and sense it. The boom in San Angelo—small though it had been—was gone. New houses stood vacant. The engineer we hired when things were flush left for Dallas, happy that his new employer had agreed to pick up the paper on his house after it had stood empty for more than a year. And it just continued to get worse.

I remember a conversation I had last summer with the secretary in our field office. I had increased my calls since early ’86, when oil prices slid to the teens and my worry started to go into high gear.

“I’m so depressed,” she said in her twang. “Tesoro’s dropped the price to thirteen dollars a barrel. You all are barely covering your notes at the bank. And we need to transfer some money for those pump jacks from savings to operations.” I was depressed, too, thinking of my brother and the pumper out in that god-awful hot field, doing a work over on a well. “We went from the best of times to the worst of times,” she said, a tone in her voice that reminded me of people who became pious after having something happen—something bad, usually.

So now I pray. That the price of oil will go up because I still owe $22,000 to Texas Commerce. I owe an untidy sum to RepublicBank Austin too. A few months ago my banker sent me yet another very nasty letter—the bank does not find me as charming as it did in 1982. And after a year during which my swimming pool felt like the slipperiest and greenest of knots around my neck, I have finally sold my house. In the meantime, I’ve still got my mink.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- San Angelo