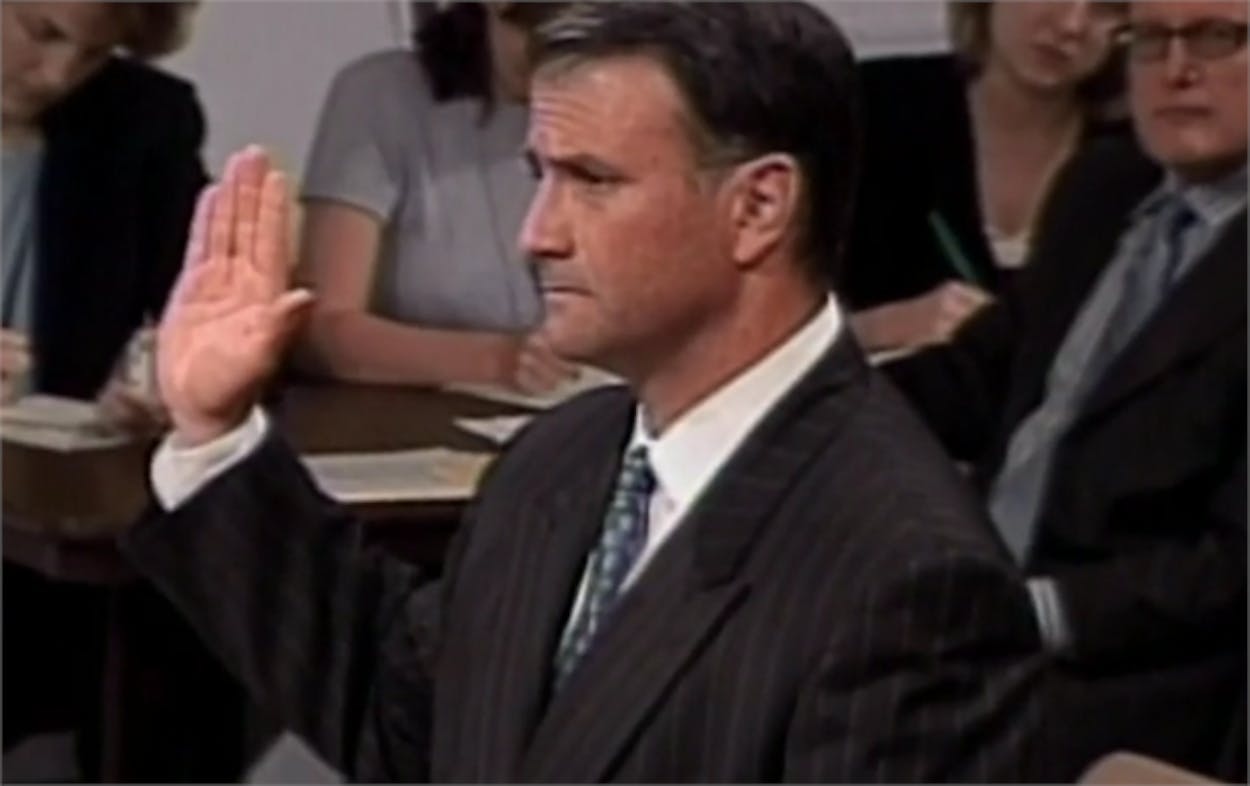

Jack Abramoff apologized profusely for the damage he did to El Paso’s Tigua Indian tribe during an interview with El Paso Times editor Robert Moore.

“I’m horribly sorry for the things I did that were wrong, that I wish I could make it up to them, I wish I could some way give or do something to make it better,” Abramoff told Moore in a twenty-minute phone interview. “I’m sorry first of all for failing them, that I wasn’t able to succeed. I’m sorry that I benefited from the deal they did with Scanlon, that I got money for that . . . I’m sorry that our relationship deteriorated. I’m sorry for any coarse and stupid language I used.”

Moore points out that Abramoff’s motives for talking might not be entirely pure, as he is trying to publicize his book, Capitol Punishment. (Tucker Carlson threw Abramoff a book party in Washington last month.)

Tigua Lt. Gov. Carlos Hisa, who worked with Abramoff to try to reopen the tribe’s Speaking Rock Casino, didn’t buy his apology: “I do not accept their apology. I do not find it sincere. The time to come back and apologize is when the investigation was going on,” Hisa told Moore.

Moore rehashes the Abramoff scandal, which started when the lobbyist worked to close the Tigua’s Speaking Rock Casino. Abramoff considered Speaking Rock to be a threat to western Louisiana casinos owned by the Louisiana Coushatta, his client, but after the El Paso casino closed, Abramoff switched sides, Moore wrote. The tribe hired Abramoff associate Michael Scanlon, a former aid to Tom Delay, for a $4.2 million fee, and while Abramoff offered his consulting services pro bono to work to reopen the casino, he was illegally paid $1.8 million by Scanlon.

“In his interview with the Times, Abramoff said he devised the plan as a way to short-circuit attempts in the Texas Legislature to legalize Indian gaming in the state. He would push through federal legislation to legalize gaming for the Tiguas, leaving the Alabama Coushatta on their own and easier to defeat at the state level,” Moore wrote.

Abramoff worked with Ohio congressman Bob Ney to insert pro-Tigua language into a bill designed to fix problems with America’s election system that cropped up during the 2000 presidential race. But the scheme unraveled when Chris Dodd wouldn’t get on board. The Washington Post ran an investigation on Abramoff’s dealings with Indian casinos in 2004 and, two years later, Abramoff pleaded guilty to corruption charges. In 2010, he was released from prison having served a little more than half of his six-year sentence.

The $4.2 million the tribe handed Scanlon and Abramoff could have put to much better use in the tough economic times the tribe faced in the wake of the casino’s closure, Hisa said. “When the casino closed down . . . we had to cut down on a lot of the services we were providing. That money could have been used to continue providing those services,” Hisa told Moore.

The four-part package also includes: a sidebar on the slurs Jack Abramoff used privately against Indians; a piece on the Ysleta del Sur Pueblo and the difficulties the tribe faced in the wake of the casino’s closure; and a handy timeline of the casino’s closure and Abramoff’s downfall.