IT’S ALMOST TWO ON A MONDAY morning and a who’s who of Austin roots rockers, mainstream and alternative hillbillies, punks, and graybeards are crammed into the Continental Club, arguably the finest live-music venue in the state. Heads are bobbing and hips are swaying to the pyrotechnics of 43-year-old Junior Brown, the latest electric guitar sensation in town.

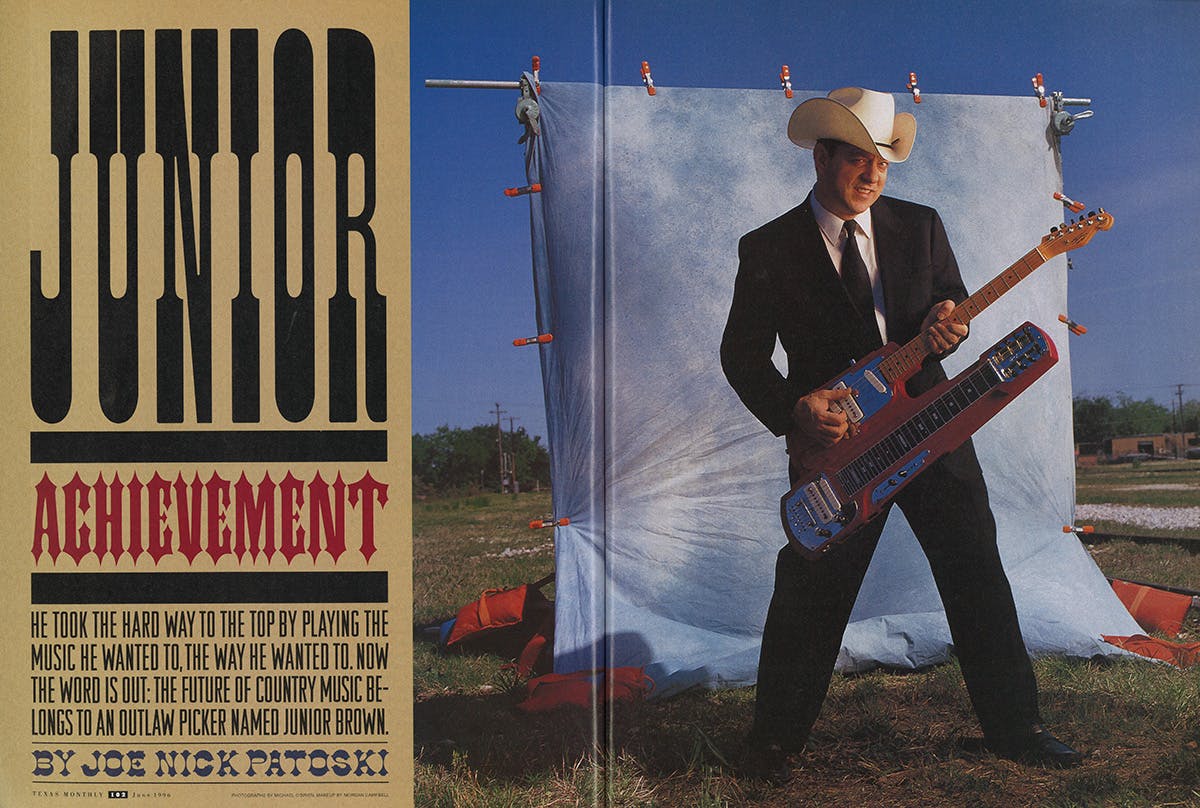

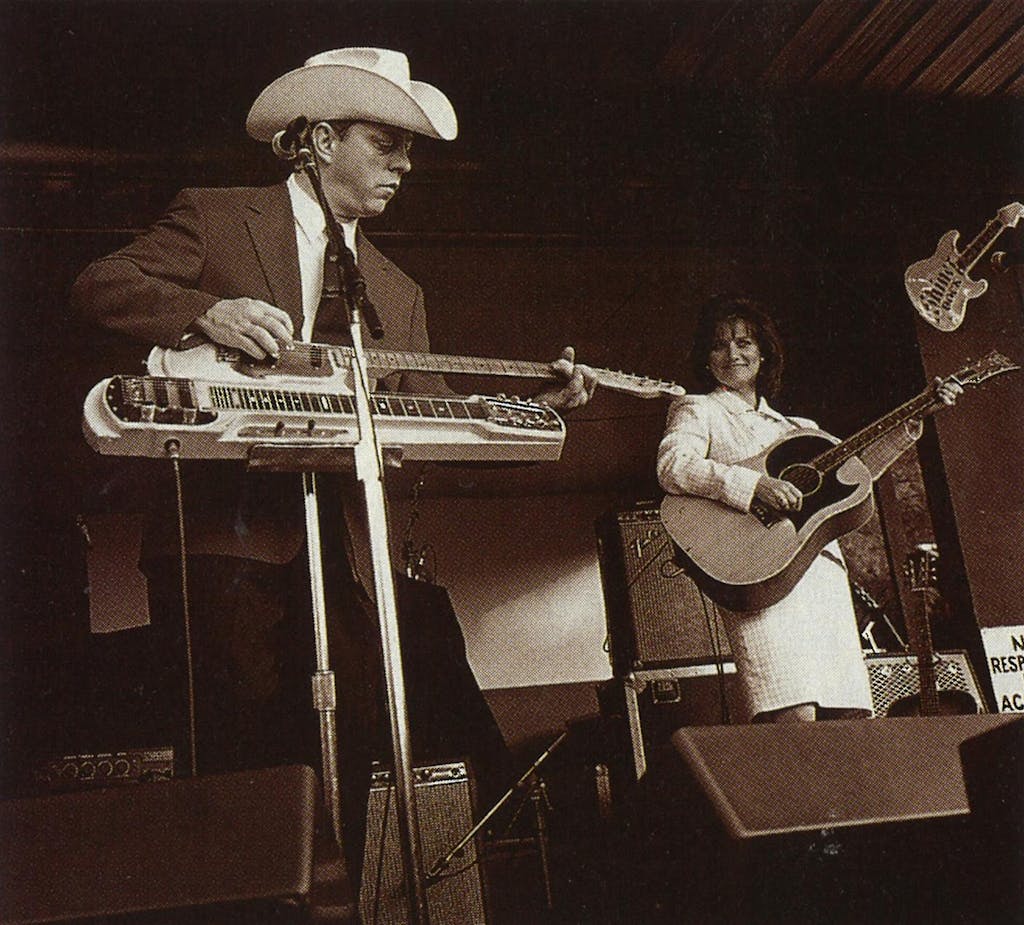

Even in a room like the Continental, where six-string virtuosos such as Stevie Ray Vaughan, Jimmie Vaughan, Bill Campbell, David Grissom, Eric Johnson, Charlie Sexton, and John Reed have performed on its storied stage, the doleful, moon-eyed Brown stands out. His bent-brim Western hat, black coat, white shirt, and dark tie may give him a kind of detached, corn pone cool, but the guitar wizardry he displays as he rips through an amazing and studiously eclectic set—quoting passages from Jimi Hendrix, Ernest Tubb, the Ventures, Jimmie Rodgers, Leon McAuliffe, and Roy Smeck amidst his own compositions—defies typecasting. Brown is backed up by his engaging wife, Tanya Rae, on rhythm guitar; Steve Layne on upright bass; and Tom Lewis, who works a single snare drum with brushes.

The ensemble sound, his retro stage dress, and his unique picking style aren’t the only things about Junior Brown that set him apart. The instrument he plays is a unique double-necked invention he calls the guit-steel, which allows him to express the competing sounds in his head: conventional boogies and low-down blues on the guitar part; weepy, lonesome moans, simulations of gears shifting on a diesel truck, and sustained-note wobbles on the steel part. “If I have to play and sing with just one instrument, that’s not me,” he says. “I like to switch.”

The guit-steel is emblematic of Junior Brown and his place in modern music. Like the instrument, he’s a maverick who has traveled the long road of obscurity because of his uncompromising (and sometimes difficult) nature and his commitment to hard-core country music before it evolved into the bland pop-rock hybrid heard on the radio today. But unlike most of his brethren who root themselves in the classics, Junior is threatening to become a full-blown Nashville star, while remaining resolutely against the grain. There have been sit-ins with the house band on Saturday Night Live, an appearance on the Grand Ole Opry, two shots on Late Night with Conan O’Brien, one on The Late Show with David Letterman, nominations this year for a Grammy and an Academy of Country Music Award, and in the past eight months, two number one videos, “Highway Patrol” and “My Wife Thinks You’re Dead,” on the Nashville Network. Brown’s first big-budget album, Semi-Crazy, has been issued to critical raves, and he sings a bitchin’ lead to “409” on the upcoming Beach Boys Go Nashville—backed with vocal harmonies by the Boys themselves—and playing perhaps the first surf-steel solo ever recorded.

As a result, the Sunday night gigs at the Continental are becoming few and far between. Right now, Brown is on tour with the Mavericks, a popular young country band from Miami, through the end of the year. I caught up with the tour at the John T. Floore Country Store, a vintage Texas dance hall in Helotes, twenty miles northwest of San Antonio. Many of Brown’s country heroes have played at Floore’s over the years, including one who pulls his touring bus alongside Junior’s. Johnny Bush, the Country Caruso, who got his start as one of Ray Price’s Cherokee Cowboys with Willie Nelson and who later popularized songs such as “Whiskey River” and “There Stands the Glass,” has come to pay his respects. Brown naturally treats Bush like visiting royalty, asking him to join him onstage.

Most of the two thousand on hand who’ve come to see the Mavericks have probably never heard of Johnny Bush or Brown’s other heroes, such as Ernest Tubb and Bob Wills. Part of Junior’s mission onstage, with the songs he plays and how he plays them, is to show his younger listeners how the present and future of country music are in its past. He and Tanya Rae are dedicated to getting a sound few other country musicians know how to get—one that is authentic and fresh. And whatever Junior’s guit-steel can’t say for him, his booming baritone—“My cornball singing voice,” as he calls it—does. The music quickly grabs the crowd at Floore’s. Some are clearly country purists, rejuvenated by Brown; others, like the high school kid with the buzz cut and the urbane black gentleman, seem pulled in by the novelty of it all. All are singing along with Junior, nearly shouting the refrain: “You’re wanted by the po-lice/And my wife thinks you’re dead.”

It’s one thing for someone to say he has dedicated himself to keeping country country, but Junior Brown means it. “I’ve waited a long time to do this,” he explained before the show at Floore’s. The son of an itinerant college music professor who grew up in Indiana and Maryland, Brown says a revelation came to him while watching television on Saturday afternoons when syndicated half-hour music programs brought the likes of Ernest Tubb and Porter Wagoner into his living room, introducing Brown to the Southern stylistic nuances of big hair, gaudy outfits, and the music of his future. He was particularly drawn to the sound created by one of Tubb’s Texas Troubadours, Buddy Charlton. “That was the first time I ever heard pedal steel guitar,” Junior says dreamily. “It was Hawaii—the palm trees swaying, the waves. The steel sounded like Hawaii looks.”

When Brown started knocking around clubs in Albuquerque, New Mexico, as a teenager in the mid-sixties, he was oriented to rock and roll. In 1966 he had a face-to-face encounter with Jimi Hendrix, who remains a personal favorite. But by the early seventies, Junior had gravitated to the honky-tonk sound he had heard on television. His entrée was New Mexico’s first long-haired country band, the Last Mile Ramblers, who played in the tradition of Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings. The band held forth every Sunday afternoon at the Golden Inn in the Sandia Mountains outside of Albuquerque, a gig that became famous for the cross section of humanity it attracted: bikers, hippie communards, rednecks, and outlaws. In 1973 Brown bought a pedal steel.

But Junior found that the old style of country was being scorned. “People were in such a hurry to cover up that stuff because it represented bigotry and what it was like to be a stupid hick,” Brown says. He quickly discovered how hard it was to earn a living with that musical focus. “I was a pariah,” he says. “People made fun of me. As much money as I could’ve made doing Gatlin Brothers covers, I stuck with Ernest Tubb covers, and I was called all sorts of names. If you didn’t play ‘Redneck Mother,’ you couldn’t keep a job.”

A few years later Brown joined Dusty Drapes and the Dusters, another progressive-country band popular in Colorado, then the Billy Spears Band, a country-rock group based in Lawrence, Kansas. In 1979 he landed in Austin, where he had played on several occasions, and joined Alvin Crow’s Western swing band. That led to a brief stint with the cow-punk band Rank and File (Junior replaced Alejandro Escovedo), as well as pickup gigs with Asleep at the Wheel and Gary P. Nunn. But while playing as a sideman as he strove to perfect his own sound, Brown could be more than semi- crazy—he could be downright difficult. Then in 1984 Speedy Sparks, a noted bass player on the Austin club scene, approached Junior: He was starting a new label, Dynamic, and he wanted Junior to record a single. The five hundred copies of “Too Many Nights in the Roadhouse,” with “Gotta Get Up Every Morning (Just to Say Goodnight to You)” on the flip side, that Sparks pressed in 1984 were the incentive Junior needed to head up his own band. It would be six years before a follow-up recording, 12 Shades of Brown, a cassette Junior released on his own JRB label and noted for the signature tune, “My Baby Don’t Dance to Nothin’ But Ernest Tubb”; two Polynesian nuggets, “Hillbilly Hula Gal” and “Coconut Island”; and a pro-farmer anthem, “Don’t Sell the Farm.” Still, work was hard to find.

Then Leon McAuliffe, the original steel guitarist for Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys, urged Junior to join the faculty, teaching both guitar and steel, at Rogers State College in Claremore, Oklahoma, where McAuliffe was the director of a country music program. Brown, broke and between gigs, did so with some reluctance; he wanted to play, not teach. His brief tenure turned out to be time well spent: He met and fell in love with one of his students, Tanya Rae, who became the stabilizing presence in his life as well as his musical foil. With Tanya Rae at his side, Junior began to write the songs that would take him from sideman to featured attraction.

The couple moved to Nashville, but their big break never materialized. Money earmarked for overdue bills became gas money back to Texas. At least in Austin, Junior’s instrumental prowess was a semi-bankable commodity. “I got a job on the second night I was in town,” he says. “I was making money.”

All the while, Junior was honing his sound. “On a visit to Hawaii, I learned how nice it is to tone the drums down and the rhythm guitar up, which is the opposite of what everyone in Nashville is doing these days. I started developing a sound with Tanya’s rhythm guitar as the foundation.” His quest sometimes resulted in heated words exchanged onstage with Tanya Rae and a revolving cast of bassists and drummers.

In 1991 a fan named Casey Monahan, then and current director of the Texas Music Office, put up the money for Junior to make a second album for Dynamic. But before Guit With It was mastered, Nashville’s Curb Records came calling and subsequently released that record and reissued 12 Shades. Last year Curb put out an EP of remixed songs called Junior High.

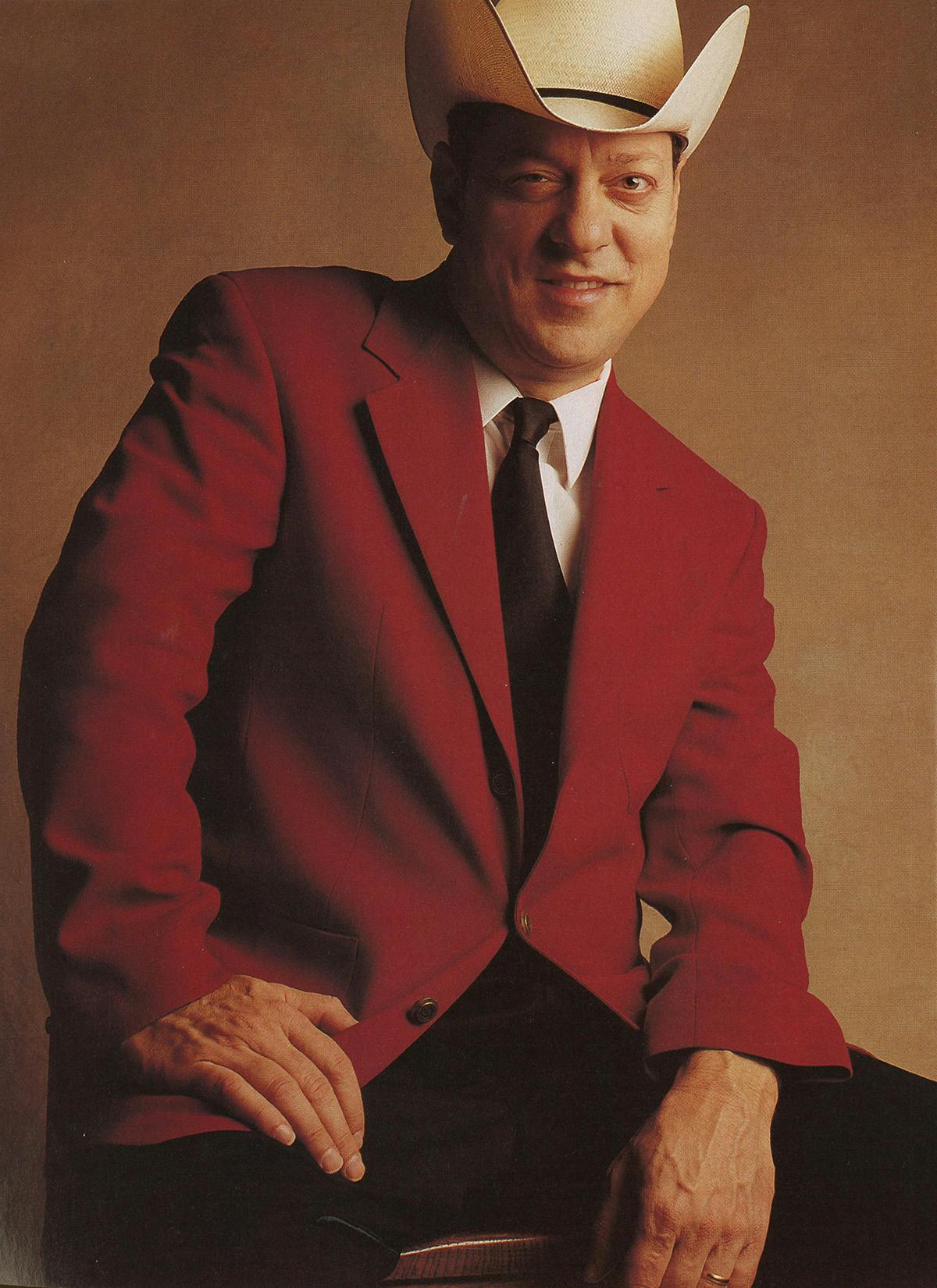

The timing couldn’t have been better. The alternative-country movement that includes national bands like Son Volt and Texas bands like the Derailers and the Hollisters, neatly coincided with Junior’s growing popularity. “I just finally found a way to package myself: the singing, the writing, the guit-steel, and the band,” he says. “I used to be bitter. Now I don’t have a reason to be bitter anymore.” In his ornery way, though, Brown remains unimpressed with the anti-Nashville crowd he was associated with. “I see a lot of Western suits, but I don’t see much under the suits,” he says. “It’s like fifties rock—either you were there or you’re a poseur. And I see a lot of poseurs. If you’re going to put on a Hank Williams suit, you better have something to say.” Even the comparisons to Tubb are off base, he insists. “I sing with vibrato, and Ernest never did.”

The fussing may have ceased onstage (“I have been picky in the past, but it’s got to the point where I’m getting the sound I want,” he explains), but there is still plenty for Junior to be cranky about. He loathes bad food on the road—“Too much red meat and not enough Luby’s”—and complains about the overcooked, gristly steak he is served before the show at a restaurant next door. (Yet, for dessert at that same meal, he has slices of barbecued beef brisket.)

More significant is his development as a singer-songwriter with a penchant for wordplay: “She’s venom wearing denim/A viper dressed in blue/Tight-fitting jeans are all she needs/To put her bite on you.”

“I’m prompted by boredom of subject matter,” Brown observes. “I get sick of writing about love, kisses, cheating. Writers take themselves too seriously. Lighten up, America. Nobody writes fun songs anymore. Everybody’s trying to be cool.”

Junior has made it hep to be square. The originals on Semi-Crazy, such as “Joe the Singing Janitor” (“I’m in your school room, your pool room, your office, and your hall”), the autobiographical “I Hung It Up,” and the title cut, a duet with Red Simpson that is the first decent truckin’ song in more than a decade, may sound silly, but they stick with you like well-crafted country songs are supposed to.

“We’re at the end of a very important era,” Brown proclaims. “You can still go to the Grand Ole Opry and see Hank Snow, Jimmy Dickens, and Kitty Wells. But we’re right at the end.” And emulating the fashion of the good old days is not enough. The proof is in the picking.

“The techniques for playing the music were superior in the fifties and sixties, compared to the eighties and nineties,” Brown says. “What they’ve been doing in Nashville since the mid-seventies is rock and roll rhythm sections with country on top. They don’t play country music anymore in Nashville. They don’t know how.”

Junior knows. So does Johnny Bush, who is called to the stage in the middle of Junior’s performance at Floore’s. Making sure the crowd is familiar with his guest, Junior calls him “one of my greatest influences.” The two proceed to trade vocals on a Bush composition about sadness and resolve titled “Way to Survive.” When the song is over, Junior gives Johnny Bush his due, calling out his name. “Great job, John. Thanks, buddy.”

Junior Brown sounds just like those country music stars he used to see on television when he was a kid, when country was still country, and young Junior Brown had a song in his head, trying to get it out.

- More About:

- Music

- Longreads

- Country Music

- Austin