This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Chances are you’re getting something from Roger Horchow for Christmas this year. The Horchow Collection is the most successful strictly mail-order series of specialty catalogs in the country. In four years they have become the model other catalogs have widely emulated and shamelessly imitated. This year Horchow expects to gross $21 million in sales. And, though it may come as a surprise to people who equate Horchow’s brand of chic with East or West Coast sophistication, he runs his entire operation from a warehouse complex in a Dallas suburb.

“Roger Horchow,” wrote Eugenia Sheppard in her nationally syndicated fashion column, “changed the mail-order catalog from something deadly dull to a publication that women can hardly wait to open.” People in Texas, of course, have had that same sense of anticipation for years about the Neiman-Marcus Christmas catalog—and there are those in the mail-order industry who say Horchow has borrowed freely from Neiman’s in other ways as well. But it’s a fact that sitting down with a Horchow Collection catalog can be a seductive experience. It appeals to everyone from the busy housewife or working woman, for whom catalogs save time and energy, to Robert Redford, who has bought a few things for his Utah ranch, and Princess Grace, who ordered Lucite bathroom fixtures for the Monaco palace from Horchow.

The Horchow Collection may be the biggest thing to hit the mail-order business since Montgomery Ward sent its first catalog to Midwest rural areas in 1872. For a long time catalogs were mainly a way for mass merchants to woo the rural customer; now specialty catalogs are becoming a part of the urban routine, almost as commonplace as shopping malls. The development that opened the way for Horchow was the luxury catalogs promoted by retail stores like Neiman’s. But Horchow’s are the first luxury catalogs that are entirely mail order, without a store to back them up. Horchow is largely responsible, through the precedent he has set, for the 20 per cent increase in the number of catalog companies during the last five years. And he has helped make the mail-order business into a $48 billion industry.

Samuel Roger Horchow isn’t just a business visionary who saw that mail order is to the seventies what discount stores were to the sixties. He has occupied several high rungs on the corporate ladder: president of Boston-based Design Research, chairman of the board of Georg Jensen, and founder of the Kenton Collection prestige mail-order catalog, which Horchow later bought. He also holds the distinction of being the only executive to leave Neiman-Marcus and be hired again—only to leave again—which merely added to the mystery that surrounds his business reputation.

Horchow’s success is due to a number of factors, but perhaps the most important is his mailing list. Says a Horchow competitor, “The mailing list is the single most significant asset in the direct-mail business. If there was a fire, I’d grab my list first.” Compile the right list and the chances of making a sale, even if the catalog is sent unsolicited, are as high as fifty-fifty, according to an A. C. Nielsen study. As the quality of the list drops off, so do the odds. Horchow has lots of names, 1.2 million at last count, of whom 650,000 have made purchases in the last two years. In addition to his list Horchow places his familiar Santa Claus postage stamp catalog ads in publications catering to the upwardly mobile, from the East Hampton Star on Long Island to the Rome Daily American. The Horchow Collection catalog is free to a reader who clips the coupon from Town & Country or the New Yorker, because he expects to do heavier business with them, while Woman’s Day and House Beautiful readers must pay $1.

He exercises total control over graphics and passes judgment on every picture used in the catalogs. Each issue is printed on coated paper, in full color, using the best production and printing techniques. He uses realistic, sophisticated settings to display the wares—some in his own home—and crisp copy to describe them. Seeing a Clovis Ruffin nightgown on a store rack is nothing like seeing it in Horchow’s catalog on one of New York’s top models. The lush graphics are Horchow’s trademark and give the catalogs a look of elegance. This year’s holiday catalog cost $1 million to produce. On every slick page Horchow pushes the “good life” at us. Do we actually need Coromandel screens in our living rooms à la Coco Chanel? French cotton sheets with a dozen tiny neck pillows? Monogrammed placemats and dominoes? Baccarat caviar servers? Antique Himalayan clothing chests?

Before deciding what items to include in the Horchow Collection, Horchow asks the question, “Would I buy this for myself?” His other concerns: Will the item gross a minimum of $5000? Will it be understood from a photograph? Will it ship well? Will it be “exclusive” to the Horchow Collection? (These items are marked in the catalog with a tiny boxed H.)

Watching 49-year-old Horchow thumb through one of his catalogs is like watching a kid raid a cookie jar. “This is fantastic! You get eight gallons of popcorn. It’s not just movie popcorn, it’s really good! And when it’s gone you have the can with your initials for a wastebasket.”

Horchow’s uncanny and practiced sense of merchandising is the key to his success. Executives in New York’s gift market I spoke with called him shrewd, sharp, and accurate. He knows what to buy when and he knows his market. Seventy per cent of his customers are women between the ages of 30 and 55. Although apparel items represent almost a third of his catalog, he dismisses any thought of setting trends. “What I’m saying to my customer, Mrs. Saint Louis or whoever she is, is don’t look to me for the advanced look. If Yves Saint Laurent makes a big splash and everything is going to be peasanty, I won’t be the first to tell you. By the time you see it in the catalog, you can feel quite comfortable that you’ll be accepted. You’re not going to be too far out and you aren’t going to be too dowdy.”

The formula must work. By October of this year Horchow’s sales were already 42 per cent ahead of last year and he had already grossed $9 million on Christmas orders. “In most years,” he told me, “the expensive items sold in those last desperate days before Christmas. This year they went instantly, as soon as the catalog was received.”

Horchow’s catalogs run between 32 and 64 pages and feature between 150 and 320 gift selections, including fashion apparel for men as well as women. Of the eleven issues mailed out this year, two were sent during the holiday season, Horchow’s busiest and most profitable period. He, his wife, and six buyers logged over 100,000 miles looking for the latest in Irish soda bread mix, German puppet theaters, and Ch’ing Dynasty goldfish bowls for his ’77 holiday books. Next year he plans to send out 25 issues, and he has also started up a second line of catalogs known as Trifles that appeals to customers with what Horchow describes as “broader taste” (perhaps “trendy” would be a better description). With only two issues of Trifles mailed out, Horchow has already turned a profit, mainly because he did not have the high costs of acquiring a mailing list, staff, and warehouse that can kill a newcomer in the business.

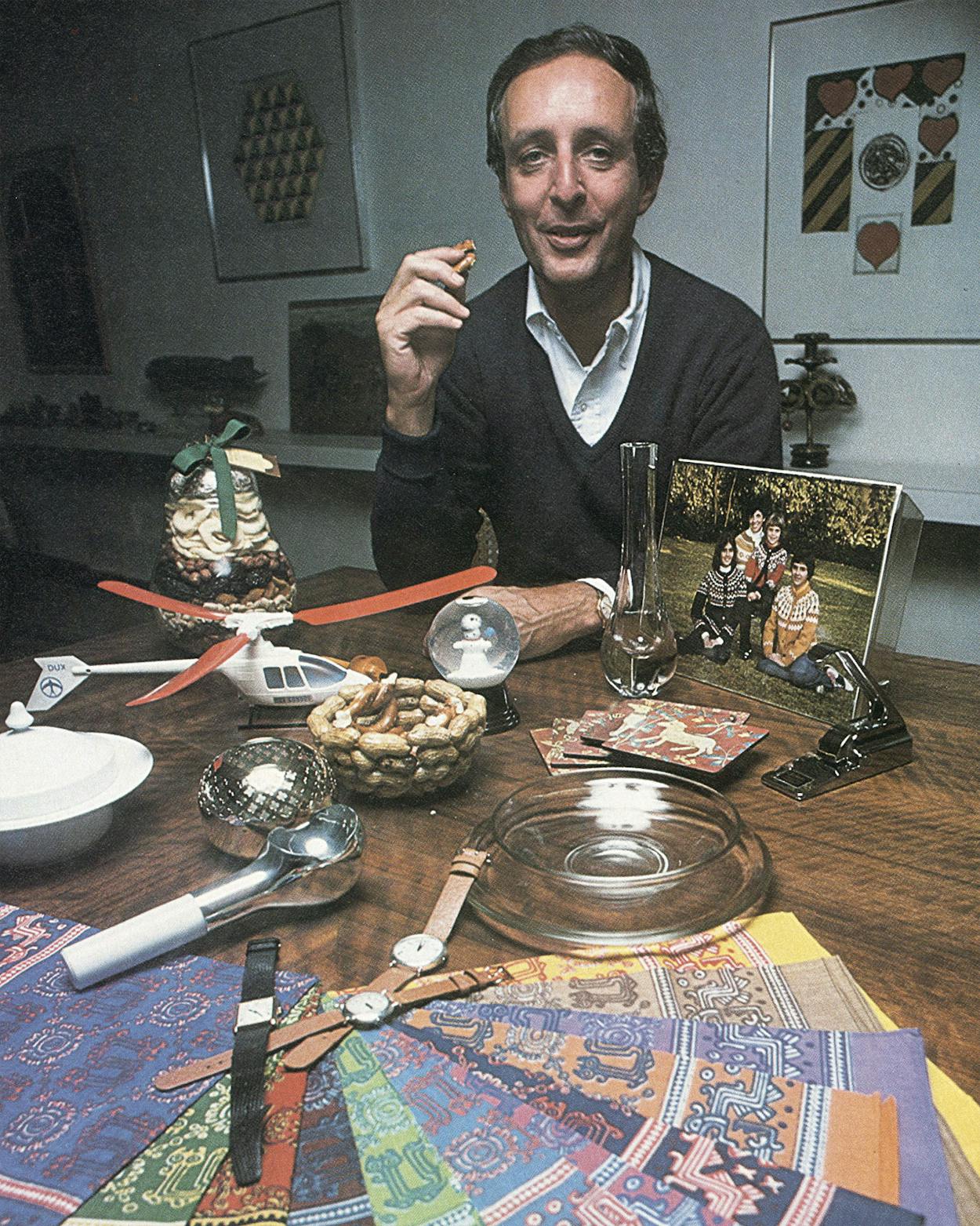

Despite the careful graphics of his catalogs, Horchow’s office in Farmer’s Branch looks like he left the window open during a Texas norther. Samples from recent buying trips, stacks of correspondence, and his children’s artwork lie scattered about. Seated behind his scarred desk, a holdover from his Jensen days, on an early fall afternoon, Horchow is dressed in buttermilk-colored slacks, a striped belt, and penny loafers—all items he mail-ordered from L. L. Bean, the famous Maine outdoor-gear store. The pale blue Hathaway T-shirt came from Neiman’s; his flaking, fading tan, from Nantucket. The person behind the catalogs is not easy to discover; he is friendly, but detached, and seldom strays from talk about business.

On the one hand, Horchow calls himself a dictator and on the other he is so egalitarian as to encourage employee suggestion boxes. A businessman to the core, he claims to want to go into government or teaching. He gives no indication of any trait that would support stories of uncontrollable outbursts and temper tantrums. In industry circles he has been called everything from a merchandising genius to a thief. Like his catalog, Horchow is certainly not ordinary.

If it hadn’t been for an Ellis Island immigration officer, you’d be ordering from the Horchowsky Collection. Like many Jewish immigrants coming to New York, Horchow’s Polish grandfather received a shortened name in his new country. Born in Cincinnati, Horchow moved to Arlington, Virginia, at the age of fourteen when his father joined the Army as a career officer. He was educated at the Hill School and Yale, and worked summers for the Federated Department Stores, early acquiring a taste for merchandising. After three years in the Army, he was sent by Federated Stores to Houston for training at Foley’s in November 1953, where, among other chores, he ironed curtains in Foley’s basement. By 1956 he had gone from the basement to the fifth floor as assistant gift buyer, and he had his first contact with Neiman-Marcus, an institution destined to figure large in his later career. Horchow turned down Neiman’s offer of a buying job at that time, but when they returned with an offer four years later he was ready to relocate in Dallas. He had become engaged and liked the idea of starting his married life in a new place.

In 1960 Horchow married Carolyn Pfeifer, a Bloomingdale’s buyer from Little Rock, Arkansas, his first and only blind date. At the urging of a friend he went to New York to meet her and they were married six months later.

In the eight years after his marriage Horchow moved from buyer to group merchandise manager to vice president at Neiman’s. He “merchandized” (an industry term that includes everything from pricing to promoting) the gift galleries, the bridal department, small leather goods, cosmetics, and the linen and bedroom shop. It was at Neiman’s that he first worked with mail orders, starting the store’s so-called “pink sale” and putting out its first catalog. “As far back as 1966 I knew the future was in mail order just by watching our weekly sales figures,” remarks Horchow.

In 1968 he went to Boston to head Design Research. He thought Marimekko cloth and Finnish furniture perfect merchandise for mail order, but management conflicts prevented Horchow’s getting to do a catalog.

Passing through Dallas one year later on the way to Mexico for vacation, Horchow lunched with Stanley Marcus, who was surprisingly cordial to his former executive. During the time Horchow had been away Marcus had sold the store to the Carter-Hawley-Hale chain. He asked Horchow if he ever thought of coming back to Neiman-Marcus. Horchow remembers he was astonished, because Marcus’ policy had always been “when you’re gone, you’re gone.” Marcus offered Horchow the vice presidency of the mail-order division, working under chairman of the board Edward Marcus, who was slated to retire in a couple of years. Horchow believed his second coming at Neiman’s held great promise, perhaps even leading to becoming president of N-M, even though his name wasn’t Marcus, so he took the job. But early in 1971 Horchow’s chances for a mail-order kingdom were squelched when Edward Marcus announced he wasn’t quite ready to retire.

“I just didn’t want to understudy any longer. When I was hired I was told in two years I’d be entirely in charge of mail order,” Horchow remembers, still sounding a bit miffed.

Then he got a call from Robert Kenmore, a former ITT whiz kid who had formed Kenton, Inc., a New York conglomerate that owned Cartier, the Family Bargain Stores, Georg Jensen, and Mark Cross. Kenmore was looking for someone to start a prestige mail-order catalog.

“The hardest day of my life was the day I had to go in to Stanley and say good-bye again. They were plenty mad and it was not pleasant at all,” Horchow recalls. “I wasn’t going to compete with them, at least I didn’t consider it competition. They did.”

Not long after he left, rumors began to circulate that Horchow had taken the Neiman-Marcus catalog mailing list. But Horchow steadfastly insists, “The only thing I took from Neiman’s was my experience. I tell you on the heads of my daughters, the only thing I’ve ever stolen was a pen in the first grade and my children can tell you the story, because it still hurts my stomach as much today as it did then.”

Says Horchow, “I think the fact that I’m still a good friend of the Marcus family—Edward, Betty, the children, the grandchildren—proves we all handled it pretty well. After all Stanley, Edward, all of them are really gentlemen. They are not heady in any way. Also, they have a store; mail order is not their whole business. We aren’t really competitors.” Of course Horchow has four blue towels in his office bathroom with MOVE OVER NEIMAN-MARCUS embroidered on them.

Part of Horchow’s contract agreement with Kenton was that he wouldn’t have to live in New York. (“No place to bring up my little princesses.”) So he remained in Dallas, where he ran Georg Jensen from a distance and started the Kenton Collection catalog in the same office he’s in today.

With the birth of the Kenton Collection, the man who had given so many ideas to Neiman-Marcus adopted Neiman’s old motto in return, “Everything under one roof.” For the first time there was one catalog that brought together many different kinds of quality items: Cartier watches, Mark Cross luggage, even Andrew Wyeth prints. But the catalog struggled in its early years. Start-up costs—purchasing a mailing list, acquiring an inventory, postage, etc.—were enormous and it took time to build up. The Kenton Collection lost $2 million during its first two years.

The rest of the trendy Kenton enterprises weren’t doing so well either. The big spending and expansion had not gone unobserved by Horchow. “Every time they bought something new, I bought something old. Everything here is second-hand furniture. We haven’t bought anything new since I’ve been here. I want to concentrate on what we’re supposed to be doing.”

Kenton sold out to Wall Street tycoon Meshulam Riklis, one of the highest paid executives in the country (his 1975 earnings were $915,866). Horchow’s airtight contract kept him from being affected by the sale, but by this time he had decided that he wanted his own catalog. He was convinced that people will buy luxury items without ever seeing them. It is a phenomenon that still strikes him as curious, but he isn’t complaining. He told Riklis, “I want to buy myself.” Riklis, cognizant of the red ink, snapped back, “What’s to buy?”

Riklis tried to stall negotiations, but Horchow persisted. Finally Riklis agreed to sell, but on his terms—$1 million in cash (the price was nonnegotiable, Riklis said), plus 15 per cent of the profits for the next five years. That has brought him roughly $500,000 more, and Riklis told Horchow the 15 per cent clause was proof he believed Horchow would succeed.

Since he had no personal wealth at the time, raising the million dollars wasn’t easy. Horchow hocked everything and borrowed from family, friends, old prep school and college buddies, even his doctor. On prominent display in his office hallway is a Lucite cube holding the original million-dollar check, signed on February 1, 1973, and drawn on the Brook Hollow National Bank. Next to it is the Silver Mailbox award, the Direct Mail Marketing Association’s Oscar for best industry catalog, which Horchow won in 1974.

One year after he bought the Kenton catalog, in January 1974, Horchow changed the name to his. Though he worried beforehand, he was determined to stamp every aspect of the business with his own personality. The name change did not hurt sales. About a year after he borrowed the $1 million, Horchow was able to buy out his investors, paying them the fabulous return of 6 to 1 or better on their original investment. He knew the catalog was taking off and that the only way to get control of the stock was to buy early in the game and to pay well.

The summer of 1974 was very big for the Horchow Collection. The name change was successful, sales soared, and recognition in the national and local business communities followed close behind. “When three very, very, very big companies tried to buy us, that was when I really knew that I had made something of myself,” Horchow says, allowing himself a rare smile. Although he won’t name the companies, one is said to have been American Express.

The attention of the big boys was a tangible sign of how far he had come in so short a time. Horchow probably wasn’t serious about selling out, but when business took a downturn shortly thereafter, he canceled the talks altogether. He saw he wasn’t going to make his projected profit of $1.5 million that year and, as he put it, “I didn’t want to look like a liar.” The problem was runaway overhead, plus a couple of bad business decisions. He opened the Weston Trading Company, a subsidiary warehouse and mail-processing operation on Long Island, to handle the large number of East Coast customers, and tried a series of specialty catalogs on cooking, art, and related subjects. None of these ventures pulled big returns, and, although Horchow remains convinced that anything can be sold through the mail, he thinks general catalogs succeed better than single-product offerings.

The setback was only temporary. Right now Horchow is planning his biggest year ever. He says he owes nothing and needs no cash for improvement. That means he can plow his profits into inventory, and he had about $5 million worth sitting in the warehouses in October (basic stock for the two holiday catalogs, with a little for the January book). The leftovers are sold through a small unadvertised outlet store in Highland Park where he discounts unordered merchandise.

Horchow seems to care far more about the abstract fact of success than about its tangible symbols. His $100,000 annual salary isn’t so grand compared to someone like Meshulam Riklis. He drives a five-year-old Oldsmobile, lives in the same Preston Hollow house he’s occupied since he came to Dallas, and travels tourist class. The suite at the posh Lombardy Hotel in midtown Manhattan, he insists, is a business necessity. “I have a book at home dating from when I first started my business called When My Ship Comes In,” Horchow says. “Carolyn and I wrote down all the things we wanted and they weren’t very many”—a trip to Italy for their daughters, a pool house, some folk art that now graces their home. Horchow relies on other people’s lust for material goods. “I don’t care about earthly possessions,” he says.

Indeed, Horchow’s main passion is a strange one for a businessman: politics. He was the first big contributor to Jimmy Carter’s Texas campaign, a fact known to few besides Bob Strauss. Horchow even put the peanut motif in his catalog long before the 1976 presidential election.

When Carter won, rumors flew around Dallas that Horchow was going to Washington. Horchow has made no secret of his wish to be secretary of commerce. His other ambition is to teach at Harvard Business School. Horchow has some connections—his former Yale roommate, Michael Egan, is associate attorney general under Carter—but, he says, “I took a hard look at our lives and my conclusion was that it’s fabulous to serve your country but this is the wrong time. Maybe in three or four years. Now we have to run the business.”

And the business has proved a good outlet for his social conscience. Last year he commissioned five Bilston and Battersea commemorative boxes for the catalog and donated $20,000 from the sales to the American Institute for Public Service. He’s done similar projects for the American Wildlife Association and Children’s Television Workshop. He assists with Texas fund raising for Yale and also serves on the boards of the Dallas Museum of Fine Arts, the Dallas Symphony, Channel 13, the American Heart Association, and the American Jewish Committee.

Closer to home, Horchow also treats his employees well. He regularly employs 250 people, building to 500 during Christmas, and commissions agents in nearly every country where he buys merchandise. He not only pays well but also has a generous 8 per cent profit sharing plan.

Only a couple of things ruffle the usually unflappable Roger Horchow. Very aware of his imitators, he is not flattered. “Even our name has been copied,” he says. “Whoever used the word ‘collection’ before we did? I remember when I was interviewing for jobs back in 1969 and I went to lunch with some Saks Fifth Avenue executives. They told me mail order would never be important and that it was the thing they were least interested in. And now they have the Folio Collection catalog!”

What irks Horchow most is the “lack of originality” other people demonstrate when they start catalogs. “The first one who knocked us off was American Express. They were so damned unoriginal that out of 240 items in their catalog, 55 were identical to ours.” Horchow wrote an angry letter, but he apparently wasn’t upset enough to stop honoring their credit card. Says Horchow, “They are all welcome to try to copy me but they can’t, because they don’t know what’s in my mind or what I discussed three hours ago.”

Most people who do business with Horchow, from employees to designers, range from satisfied to overjoyed, though there are some notable exceptions. Surely one of the best Christmas gifts Mollie Parnis received this year was the report that Horchow sold so many of her $260 Ultrasuede shirt dresses ($350,000 worth) so quickly (within ten days after the catalog went out) that he had to reorder.

Horchow not only gives designers business; he has put some of them in business. Andrew Downs, 34, a New York designer of menswear and accessories, says, “Roger believed in me enough to get me in my own mail-order company. My initial order from Horchow was $15,000 a year for a plaid bag I designed, and I was doing almost $150,000 a year with him when I stopped to do my catalog. It all happened because the Horchow name is magic in retail circles. A buyer will come to you in a minute when you tell them you’ve sold to Horchow.”

There are, however, some designers for whom the Horchow name connotes something less than magic. One is jewelry designer Barry Kieselstein-Cord, who had his differences with Horchow over a $145 gold falcon pendant that the Horchow Collection reordered after it appeared to be selling well in the catalog. But the projections were wrong, and Horchow tried to cancel. There was an angry exchange of letters, some dispute about whether Kieselstein-Cord would agree to accept the cancellation or take the merchandise back for future credit, and Horchow eventually dumped the falcons at a discount when Kieselstein-Cord could have used them to fill other orders. “This entire affair with Horchow made me leery about independent catalogs,” he says. “The only books I go into now are those supported by retail stores.”

One designer was disappointed to have Horchow reject her idea for cocktail napkins, but she was outraged when napkins resembling her design popped up in a later Horchow catalog. The problem, of course, is that more than one person can think up roughly the same idea at roughly the same time, and losers invariably think their ideas were stolen; it is one of the built-in hazards of the commercial arts.

The very nature of Horchow’s business is so competitive that controversy and hard feelings are unavoidable at times. Furthermore, designers seem to thrive on rumor and gossip, so some cattiness is to be expected. Even so, Horchow’s rifts with people in the business are legendary within the merchandising community. There is said to be bad blood between Horchow and Susan Edmonston of Kaleidoscope, a $16 million-plus mail-order catalog. For her first two mailings she purchased Horchow’s mailing list. (His current rate is $ 100 per 1000 names, or about a dime apiece for your name and mine, and he’ll sell it to almost anyone, as you’ll soon find out if you order from Horchow, unless you request otherwise.) When Edmonston tried to buy the list a third time, she was told that she was “too competitive” with the Horchow Collection. She and Horchow have never officially met, but they know each other well enough to practice avoidance when they happen to be at the same showroom or market.

An even more serious feud was sizzling between Horchow and his former creative director, Jo-Von Tucker. She worked with him during his Neiman’s days and contributed heavily to the early artistry of the Kenton Collection catalog. She gave up her other accounts to concentrate solely on Horchow, then heard rumors that he was shopping for other photography services. She quit, he blew up, and about the only thing they agree on now is that the episode was one of the worst moments in their professional lives. Two years later, in fact, her name causes him to blanch. It is obvious he has held onto the grudge tenaciously, forgetting his own painful leave-taking from the Marcuses.

Of such stories Horchow says, “a lot of people feel I’m hard as hell to deal with, but I just expect others to hold up their end of the bargain. It’s very frustrating the way people will turn around, once you’ve made them popular by putting them in four or five catalogs, and then they are off because they think the grass is greener elsewhere.”

Mostly, however, Horchow likes to talk about the bright future of mail order in general and Roger Horchow in particular. He tells about a case study he remembers from a seminar at the Harvard Business School. “The Brown Shoe Company always had a shoe for your maid, a shoe for your wife, and a shoe for your boss’ wife. The idea is to compete with yourself. If things get bad and people start trading down, you’ll be right there to sell them something else.”

- More About:

- Style & Design

- Business

- TM Classics

- Dallas