WHEN I WAS A STUDENT at the University of Texas at Austin in the early nineties, a story got around about the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center. It didn’t qualify as campus legend; too few people had heard it. It was more like a rumor, and it went like this: If you rode up to the fifth floor of the HRC—that is, if you could find the HRC, which was a chore before $14.5 million in renovations were completed this spring—you could fill out a request form and then be allowed to look at the journal Jack Kerouac kept while he was writing On the Road. That’s right: the very journal, written in Kerouac’s own hand in a small, spiral-bound notebook that was no doubt kept in the back pocket of his dirty blue jeans while he was, literally, on the road.

But there was one thing you had to keep in mind. To see the journal, you had to have a valid reason. And if you weren’t writing a biography of Kerouac or making a documentary on the Beats and you didn’t feel comfortable lying, you could still get in if you remembered the magic word. Write “inspiration” in the space marked “purpose of research,” and the keys to the kingdom were yours.

I didn’t give the story much thought at the time. But a few years later, when I was between careers and in possession of plenty of free time, I went by the HRC to suss things out. It happened that the rumor was true. A particularly helpful librarian pointed me not just to Kerouac’s journal but to other items in the Kerouac collection. In papers obtained from the widow of Neal Cassady, Kerouac’s friend and role model, were dozens of letters Kerouac wrote while he was struggling to find his voice. The stream-of-consciousness flow was there in his prose but none of the confidence. That changed, though, with the letters he wrote after On the Road was published. Suddenly his signature was taking up half a page.

An afternoon at the HRC turned into a week. I’d arrive in the morning, think of an artist, and ask for the moon. Half an hour later, I’d be holding a handwritten draft of Dylan Thomas’ Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night or a letter from jazz saxophonist Charlie Parker written during his court-ordered dry-out at a California mental hospital. (Parker’s handwriting was immaculate; each g looked like it had taken five minutes to write. But the message was less deliberate: “Man—please come right down here and get me out of this joint. I’m about to blow my top!”)

I’ve since learned just how much HRC there is. It owns one of the surviving copies of the Gutenberg Bible, the first book printed with movable type. It owns the first photograph ever taken. As an American cultural archive, it is ranked not far behind the Library of Congress and the New York Public Library; the only university libraries consistently mentioned in the same breath are the Beinecke at Yale and the Houghton at Harvard. The HRC has the personal papers—manuscripts, journals, letters, and the like—of a long list of true literary lions, including Joyce, Twain, Faulkner, Beckett, Hemingway, Ginsberg, Singer, Wilde, Waugh, and Pynchon. Its photography collection is one of the finest in the world, with thousands of images from the Farm Security Administration’s famous photo project and more than a million taken by San Antonio panoramic photographer E. O. Goldbeck. Then there are the oddities that show the artist behind the art. Gertrude Stein’s pens. Carson McCullers’ cigarette lighter. Edgar Allan Poe’s desk. Marlon Brando’s address book.

If you took the time to find the HRC, the allure was simple, and it wasn’t a desire to be nearer to celebrity. It was something more. The HRC humanizes the superhuman. When you pick up a page of Joyce’s final revisions to Ulysses, you’re not looking at the most important novel of the twentieth century. Rather, you’re glimpsing a moment in time, an instant when Joyce was just a man and Ulysses just an idea.

“RANSOM BELIEVED THAT THE BOOK represented the end of the process,” HRC director Tom Staley told me in his office one morning in August. “You get the story down, you print it, and then other people read it. But where did that story come from? What you really ought to study is this trajectory, as I call it, of the imagination. What are the false notes? What was thrown out; what was kept? So in the end, what the student studies is the creative process.”

That was Harry Ransom’s vision when, as vice president and provost of UT, he founded the Humanities Research Center in 1957, and it still guides Staley as he presides over almost everything that happens at the HRC: fundraising, acquisitions, conservation, exhibits. Staley has the refined charm of a Pennsylvania-born Fulbright scholar turned university administrator. Yet he’s a passionate storyteller, particularly when the conversation gets around to the right topic, like James Joyce—nearly every inch of shelf and wall in Staley’s office is occupied by books about or pictures of Joyce—or the HRC.

“When Ransom decided in the fifties to make a special collection and create the center,” Staley said, “he believed Harvard and Yale had the great collections of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century literature, Cambridge and Oxford had the great early collections, and Texas was just a young university. So he decided to collect what wasn’t already gathered up, as it were, and he went after the late-nineteenth and twentieth. He bought a great deal from a man named Hanley, who was very wealthy and who lived in Bradford, Pennsylvania, which is, as you know, where the oil industry really started—they still have that famous Pennsylvania crude, which they use in motor oil. Hanley married a belly dancer named Tallulah, and her twin sister lived in the house with them. But anyhow, Hanley had this great big house that he filled full of books. His accountant would say, ‘Look, you don’t have the money for this, and it is so dangerous to keep these in this wooden house. You could burn them all.’ So Ransom would send a truck up there and buy them. And Hanley would always tell him, ‘That’s it! I’m getting out of this collecting business forever!’ And two years later Ransom would have the truck at his door again.”

Part of Ransom’s success owed to a small market for twentieth-century writers and a nearly nonexistent one for manuscripts. But it was due also to his ability as an administrator; four years after founding the HRC, he became the UT System chancellor. “There was always this myth,” said Staley, “that Ransom had made a pact with the devil, meaning [Board of Regents chair Frank C.] Erwin. ‘Let me have money for the libraries, and the football teams can do this or do that.’ Now, I don’t know if that’s true. But there is one extremely important thing in all this that people lose sight of: Ransom was able to convince the regents that the part of the Permanent University Fund that went to capital expenditures, meaning the money from the university’s oil leases that was originally used only for buildings and roads and not academic programs, could be used on books. That’s the crucial point.”

Although Ransom served as director of the HRC only from 1958 to 1961, he was a presence there throughout his chancellorship, from 1961 to 1971, and until he died, in 1976. Two years later the HRC purchased the Gutenberg Bible in his honor for $2.4 million. The next ten years saw continued growth and, more significantly, the development of a world-class conservation department, beginning in the early eighties.

Staley became the human face of the HRC in 1988. Until recently, his biggest gets were works by Pynchon, Burgess, and Singer and by contemporary British playwrights like Tom Stoppard. Although he has opted not to pursue Texas writers—they have, for the most part, deposited their papers in the Southwestern Writers Collection at Texas State University, in San Marcos—he has pushed the HRC to take a chance on first editions of contemporary authors like Jonathan Franzen and the McSweeney’s magazine crowd. “Maybe we’ll make a mistake on a writer and lose eighty bucks,” he said. “It will be historically interesting, and it’s cheaper than the alternative.”

This spring, however, Staley raised eyebrows when the HRC acquired Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein’s Watergate archive for $5 million. Announced at a time when higher-education funding was being slashed, the purchase caused a small ruckus even though it was made entirely with private funds. Staley said the controversy should have been over how little he had to pay. “The trick was finding the funds outside the university,” said Staley. Containing more than 250 reporter’s notepads, memos, photographs, drafts of stories, and All the President’s Men, both the book and the screenplay, the collection realizes Ransom’s vision in all ways but one: It is not complete. Documents relating to confidential sources, including Deep Throat, have been kept in Washington. Only after the sources die will their names be revealed and the documents sent to the HRC.

Staley’s ultimate legacy, though, will be the HRC’s heightened public profile. Its anonymity has been partly the fault of its location, or lack thereof; when Ransom started the collection, it had no home. Then, when the HRC’s current building was built, during the student uprisings of the early seventies, it looked like a bunker. “Oh, they wanted to keep people out,” said Staley. “We didn’t want any riots in here.” But six years ago Staley and the university embarked on a drive that raised $26 million to bolster the HRC’s endowment and give the facility a makeover. The resulting renovation, executed by San Antonio’s Lake/ Flato architecture firm, is striking. The front facade is now windows, with images from the collections—photographs, drawings, signatures—and pieces of text etched into the glass. Inside, for the first time ever, the HRC has space to exhibit its own materials. Staley has also beefed up the HRC’s Web presence, putting its catalog online, along with a virtual tour of the Gutenberg Bible. “There’s a possibility here for a mecca of culture,” said Staley. “And this used to be a quiet place.”

It remains quiet in the new reading room, which is where the real magic happens anyway, even for someone who walks through the stacks every day. “Oh, those Ulysses page proofs are a special place for me,” Staley said. “And Graham Greene’s collection. He did a series of postcards in which he wrote a story on the back of each one for his grandchildren. And there’s a letter Faulkner wrote to his parents from Connecticut, with a passage describing a ship that he’s watching, afloat on Long Island Sound. And he’s talking to his folks about it, and all of a sudden, my God, there, for the first time, is his writer’s voice.”

And there also, in a moment, is what makes the HRC a special place. One writer, one idea. You might call it inspiration.

Due to copyright restrictions, we are unable to publish the photos for this article on our website. To see the pictures from the Harry Ransom Center, purchase the October issue of Texas Monthly on newsstands now.

BOB WOODWARD’S WATERGATE TYPEWRITER

Woodward says he was called in to the Washington Post on Saturday June 17, 1972, and asked to cover the Watergate break-in because he was too new at the job to complain. These are the notes he took in the city-desk editor’s office that morning. They represent the exact moment the pencil hit the pad on the biggest story in the history of American journalism.

GEORGE GERSWIN SELF-CARICATURE

Drawn on the back of a restaurant table card, this self-caricature is thought to have been made by Gershwin over dinner with Gloria Swanson, as it was found among Swanson’s personal papers after the hopeless pack rat donated her huge, 500,000-page archive to the HRC. The music at the top of the drawing is the opening bar to Rhapsody in Blue.

THE FIRST PHOTOGRAPH

The HRC says the exact date of the photo is 1826, but “1827” is inscribed on the back of the original frame, in which it still rests. What is certain is that it is the world’s first photograph. It was taken by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce from the upstairs window of his family estate in central France using an eight-hour exposure on a pewter plate coated with bitumen.

WILLIAM FAULKNER’S BURNED POETRY MANUSCRIPTS

Among the HRC’s 137 Faulkner manuscripts are the handwritten final draft of Absalom, Absalom!, hand-illustrated books he wrote in his twenties, and 287 sheets of poetry burned in a 1942 fire at the garage of his mentor. This poem, written in 1925, was initially titled “If Cats Could Fly” but was later changed to “A Child Looks From His Window.”

RUSSELL LEE’S CAMERA

When Lee donated this camera to the HRC, he called it his “workhorse.” It was his primary camera when he shot for Roy Stryker’s Farm Security Administration photography project between 1936 and 1942, documenting the Great Depression with the likes of Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange, both of whose photographs are also at the HRC.

DANTE’S THE DIVINE COMEDY

These handwritten pages were completed in 1363, 42 years after Dante’s death and 90 years before the introduction of movable type to the world. These pages were written entirely by hand, as were the comments in the margins, which were made by fourteenth- and fifteenth-century scholars and teachers working on this early version of the book.

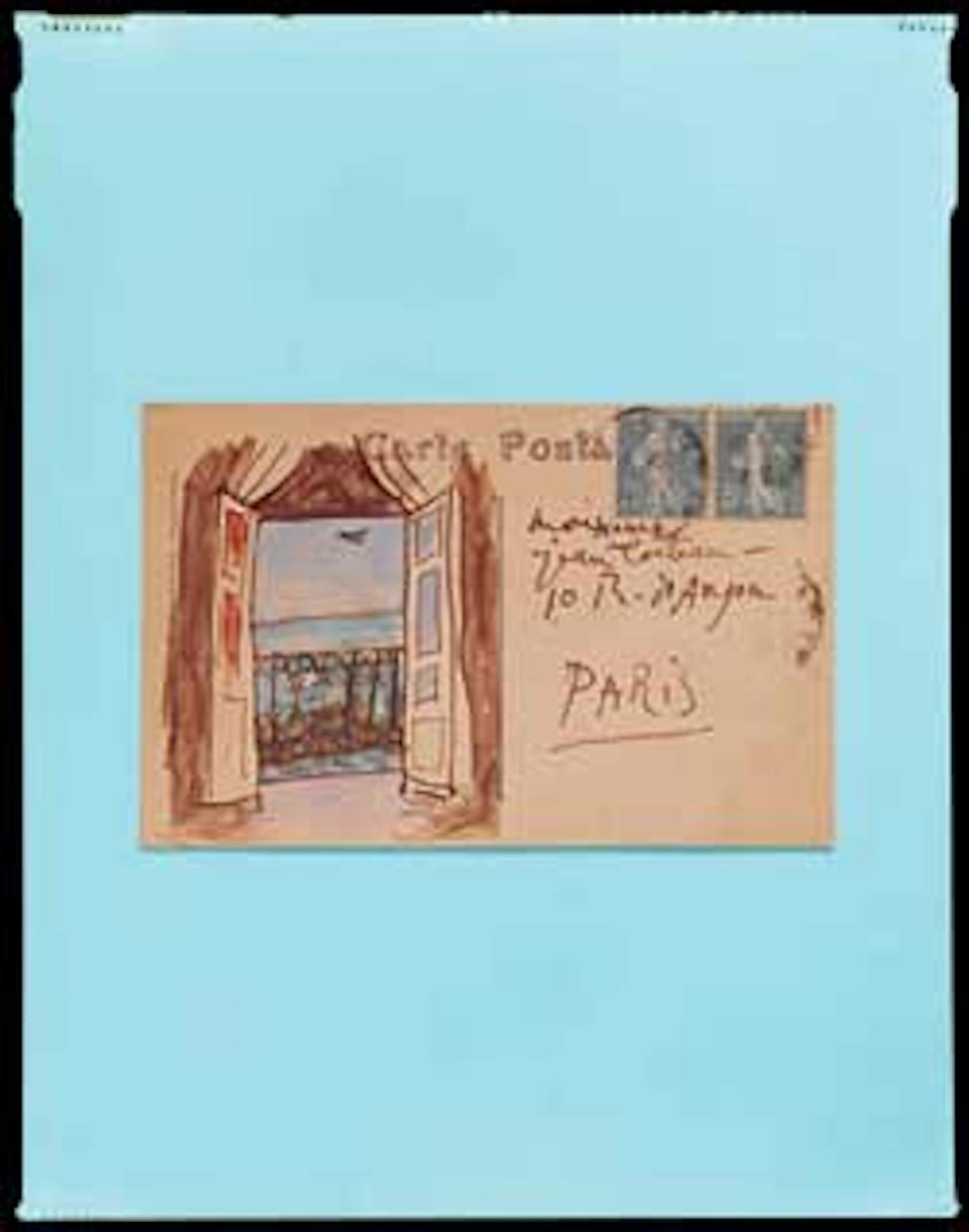

POSTCARD FROM PICASSO TO JEAN COCTEAU

On the back of this postcard from L’Hôtel Continental on the French Riviera is Picasso’s watercolor impression of his view from the room he stayed in with his first wife in 1919. The HRC has other pieces of Picasso’s correspondence, as well as a magnum of the 1953 champagne that was served at his second wedding, in 1961.

ERNEST LEHMAN’S SCRIPT TREATMENT FOR NORTH BY NORTHWEST

These notes were produced by screenwriter Lehman after a brainstorming session with director Alfred Hitchcock, in which the two finally solved the problem of getting Cary Grant out of the field in the film’s famous crop-duster scene. Lehman, now 88 and living in Los Angeles, continues to donate items to the HRC.

LEWIS CARROLL SELF PORTRAIT

Carroll is considered one of the earliest amateur photographers. The HRC owns eleven of his negatives (this one was taken in 1872) and five full albums of photographs he took of Victorian-era luminaries, family, and friends and several loose prints, including a portrait of Alice Liddell, the subject of his most famous work, Alice in Wonderland.

ALEISTER CROWLEY’S TAROT CARD

John Kirkpatrick, the HRC’s eminently dignified manuscripts curator, says that when black-clad, purple-haired researchers enter the reading room, the staff knows they want to see materials from early-twentieth-century occultist Aleister Crowley before they even ask. Crowley bought these tarot cards in 1906, nearly forty years before designing his own set.

E.E. CUMMINGS’ PAINT BOX

The majority of Cummings’ manuscripts at the HRC date to the American poet’s childhood, including a large trove of poems written between 1902 and 1914, before he turned twenty years old. But he originally wanted to be an artist, and the HRC also has some three hundred of his works, ranging from pencil sketches to watercolors of landscapes.

NAPOLEON’S DEATH MASK

Two days after the exiled French emperor died, in 1821, his doctor, Francesco Antommarchi, made a plaster cast of his face. This mask is thought to be one of several hundred copies Antommarchi made after he moved to New Orleans in 1834. Longtime theater-arts curator Frederick J. Hunter gave it to the HRC in 1971.

SIR ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE’S READING GLASSES

The HRC has many personal effects belonging to the Scotland-born creator of Sherlock Holmes, including his desk, the clothes he was wearing when he escaped his burning house in 1929, his Ouija board, and the dirty socks his wife took off of him after he died so she could make him more presentable for the afterlife.

SAMUEL BECKETT’S HANDWRITTEN MANUSCRIPT FOR WATT

As fascinating as Beckett’s daydreaming and doodling on the left-hand pages can be, the wonder of this draft of his 1953 novel is that it’s in English. The Irish playwright wrote it in the early forties, when he was posing as a Frenchman to help the Resistance in Provence. Had the Nazis seen it, his cover would have been blown.

ISAAC BASHEVIS SINGER’S TYPEWRITER

Singer worried throughout his long career that Yiddish was a dying language, so he wrote in it frequently, often on this Yiddish-keyed typewriter that he said had magic literary powers. The HRC also has his 1978 Nobel prize medal, notes on more than four thousand stories, novels, and plays, and other unpublished and untranslated writings.

GEORGE WASHINGTON’S HAIR

One of the HRC’s stranger items is a book of famous people’s hair collected in the nineteenth century by British man of letters Leigh Hunt. Not much is known about how the book was compiled, but the names of said famous people are plenty familiar: Napoléon, John Milton, Jonathan Swift, and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, among others.

FRIDA KAHLO’S DIEGO Y YO

Mexico’s most famous twentieth-century artist produced this sketch during a 1930 stay in San Francisco with her husband, Diego Rivera. If you look closely at her stomach, you can see where the famously childless Kahlo, who aborted a fetus that year, has erased an image of a baby with Rivera’s face.

NORMAN BEL GEDDES’ STREAMLINED MOTOR CAR #9

Designer Bel Geddes created this foot-and-a-half-long prototype for the cars in his sprawling “Futurama, City of Tomorrow” exhibit at the 1939 World’s Fair. The vast Bel Geddes Collection, acquired between 1958 and 2000, provides numerous examples of his famous “streamlining” techniques as applied to everything from cars to toasters.

LETTER FROM F. SCOTT FITZGERALD TO BLANCHE KNOPF

This 1928 letter from Fitzgerald to Knopf, the co-founder of the Knopf publishing house, has the author of The Great Gatsby conjugating the verb “to cocktail.” It shows up in her correspondence files in the HRC’s Knopf Collection with a copy of her response, which begins, “Dear Scotch, I think the conditional is the best and the one to be followed . . .”