This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

All aficionados of the Texas Legislature, regardless of ideology or political party, have reason to grieve over the outcome of the District 47 race for the House of Representatives. Republican Jay Reynolds of Floresville, John Connally’s hometown, was the winner, and while Mr. Reynolds may eventually turn out as well as his illustrious fellow townsman, he starts out with a black mark against his name. Had he lost, it would have been official: there would have been a Moron in the Legislature. A Morón, to be technical—Reynolds defeated Beeville Democrat Joe Morón—but who quibbles over accents with such a worthy point at stake?

Alas, the outcome of that race is symbolic of the changes taking place in the Texas Legislature. One after another the colorful characters and familiar names that have shaped Texas politics for two decades are disappearing. Gone from the Senate are Tom Creighton, the archduke of malevolence; Bill Moore, for whom the word “obstreperous” was coined; and Babe Schwartz, the one person who could keep the Legislature from doing something really awful. The now-docile House is totally different from the rowdy brawlers of the Gus Mutscher Speakership a decade ago, and many of the leaders best remembered by their nicknames—Tricky Dickie, Supersnake, the Duke of Paducah, Papa Doc—are long gone or defanged. The Legislature is rapidly becoming homogenized as the state grows more and more urban. The cities produce a different kind of candidate than the small towns: slicker, more presentable, less likely to take chances. In short, the Texas Legislature, of all places, is becoming just another parliamentary body, and while it is undoubtedly more professional and less corrupt than it used to be, it is also less . . . well, fun.

There is always hope that the current blandness is only a temporary reflection of the lengthy tenure of the two presiding officers, Billy Clayton in the House and Bill Hobby in the Senate. Clayton has already served as long as any other Speaker, and Hobby is about to tie the record for lieutenant governor. Hobby detests public squabbling—he was the chief beneficiary of the near-simultaneous demise of blood enemies Moore and Schwartz—and if he has his way, the Senate floor will be a quiet place this session as disputes are ironed out behind the closed doors of his office. But to keep control, Hobby will have to avoid the trap he built for himself last year when he played footsie with every special-interest bill that came along in return for support of his proposal, scuttled by the Killer Bee defection, to hold an early presidential primary in Texas.

As for Clayton, his style has been just the opposite of Hobby’s: stay out of most fights and let members expend their energies battling each other instead of him. The unanswered question about Clayton is how his Brilab ordeal affected him: will he be a relaxed and vindicated leader, as befits a self-announced lame duck Speaker, or will he turn mean and bitter? The success of both Hobby and Clayton will turn on how well they handle the sensitive redistricting issue, and a lot will depend on whom they put in charge of drawing the maps.

Underlying the change in legislative character is the increasing seriousness of state government. A dozen years ago a legislator worried about taxes, appropriations, teachers’ salaries, and where to find a beer after Scholz Garten closed at midnight. Most issues that are commonplace today either didn’t exist or stood no chance of getting to the floor in 1969. Proposed changes in the school finance formula barely made it out of committee in 1969, and no one understood them in the slightest; now a score of legislators know the subject backwards and forwards, and the rest get computer printouts explaining the effect of each minute change on their districts. In 1969 only insiders working on appropriations knew or cared what went on in the various state agencies; today, with every agency under scrutiny in the Sunset process, the entire Legislature gets to find out. In 1969 the only interest rate bills were pushed by loan sharks, a term of opprobrium that has all but disappeared from the political vocabulary as today’s debates focus on the nature of the national money market. Property tax reform wasn’t even discussed back then; now it is a complicated batch of laws in need of detailed amendments.

This session’s key issues will include these holdovers from previous years, plus the following six new ones that, if they won’t produce the excitement of the old days, should certainly keep lights on late in the Capitol.

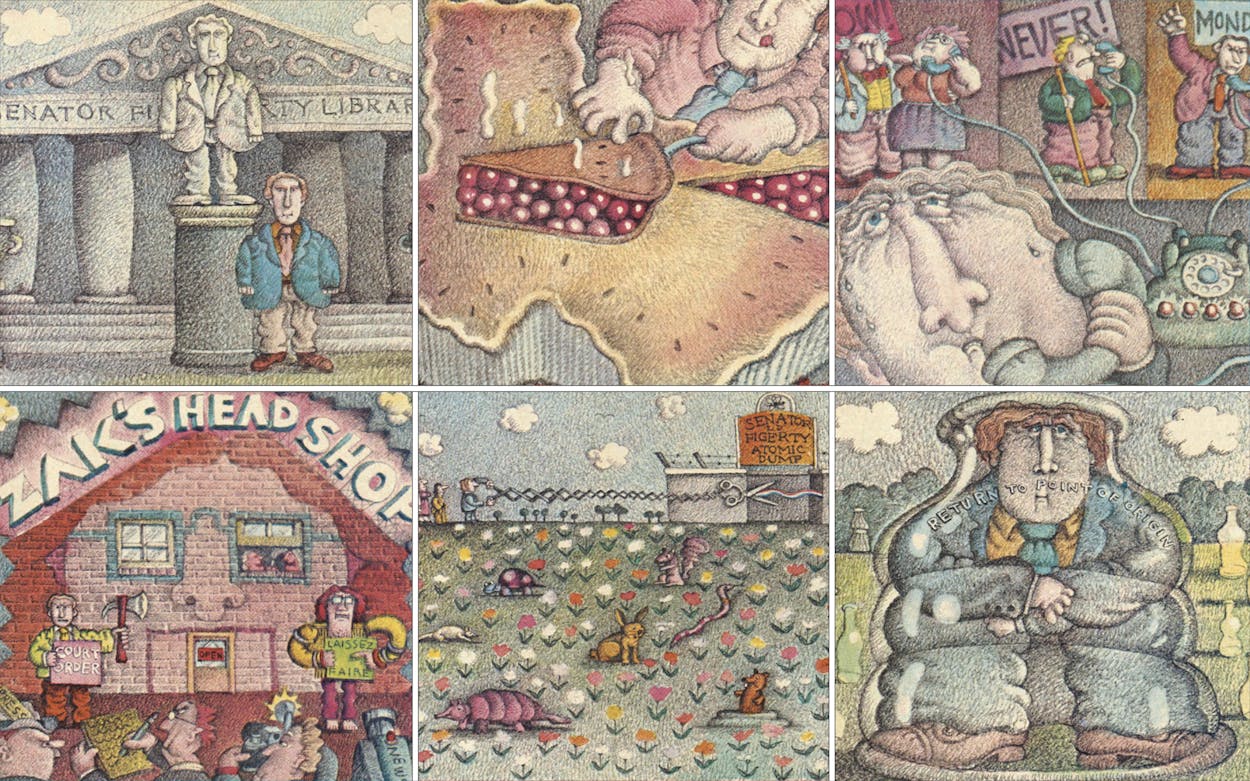

The Fine Art of Drawing

Legislative and Congressional Redistricting

It’s a good thing redistricting comes along only once every ten years. If it came up as regularly as teachers’ salaries or Sunset, the genial good ol’ boy atmosphere of the Legislature would be a thing of the past. To the Supreme Court, redistricting may be a matter of one man, one vote, but to politicians it is a matter of survival.

Every one of the 24 congressional, 31 senatorial, and 150 legislative districts must be redrawn this year, and that means 205 politicians will be fighting for their lives. Everyone wants a safe district, and to complicate matters, a few ambitious legislators would like to reserve for themselves one of the two new congressional districts to which Texas is entitled, as then-senator Barbara Jordan did a decade ago. The state’s power brokers and kingmakers will want their say, too; one of their top priorities will be security for Fort Worth congressman Jim Wright, heir apparent as Speaker of the U.S. House if the Democrats can keep control. In fact, everybody in the political game wants something: blacks will insist on state Senate seats in Houston and Dallas, trial lawyers have to protect the few remaining urban white liberals, business interests need to safeguard the diminishing ranks of urban conservative Democrats, and rural lobbies like the Texas Farm Bureau don’t want to lose too many seats to the cities.

The strongest and most insistent group will be the Republicans. In the November congressional elections across the state, GOP candidates accumulated 45 per cent of the votes, which in a fair and just world would entitle them to 11 of the state’s 24 seats. Thanks to some fancy cartography (affluent Southwest Fort Worth is dominated by a rural strip terminating in Bryan–College Station, and heavily Republican Midland is combined with Democratic Lubbock instead of other West Texas cities like San Angelo, Abilene, Big Spring, or next-door Odessa), Republicans were able to win only 5 seats and were fortunate to take 2 of those.

It is Bill Clements’s job to make certain that this hanky-panky doesn’t happen again. But his major weapon, the veto, is useful only for congressional, not legislative, redistricting. An obscure provision of the Texas constitution decrees that if the Legislature doesn’t reapportion itself in the first regular session after the census, the duty falls to a special redistricting board. Like most reforms, this one may end up having the opposite effect from its original purpose: intended to encourage the Legislature to redistrict, it may actually encourage it not to, since the mapmaking board is composed of five Democratic statewide officeholders—Speaker of the House, lieutenant governor, attorney general, comptroller, and land commissioner. Clements would have no say at all.

If a redistricting bill is too unfavorable to Republicans, Clements won’t sign it. If it is too favorable, the Legislature won’t pass it. Fortunately for the governor, a legislator’s primary motivation in redistricting is the salvation of his person, not his party. To exploit this weakness will take all the skill, power, and cunning Clements can muster.

PUF, the Magic Dragon

The College Construction Mess

Next to redistricting, college construction will be the bloodiest fight of the 67th Legislature. It may not sound exciting, but it goes right to the heart of the fundamental problem every politician faces: the choice between lofty principles (supporting the long-held notion that Texas ought to have “a university of the first class”) and self-preservation through logrolling (satisfying his local college’s insatiable appetite for more money).

The reason for the conflict is the Permanent University Fund, the oil-rich endowment that is the exclusive province of the University of Texas and Texas A&M and some of their subsidiary campuses (see Reporter: “Embarrassment of Riches,” TM, October 1980). Currently worth $1.3 billion—and that counts only the royalties from two million acres of West Texas land, not the value of the land itself—PUF is expected to top $3 billion by 1990. The income from PUF investments pays for an ambitious building program at UT with enough left over ($17 million last year) to augment the school’s legislatively authorized budget by 14 per cent.

Contrast this opulence to the plight of the other 24 state-supported schools that do not share in PUF. For years they have been able to issue construction bonds based on the proceeds of a state property tax. But the Legislature phased the levy out as part of the 1979 tax reform, planning to set up a new fund to take its place. That idea foundered in the heavy political seas of the session’s closing hours, and suddenly the unendowed colleges were left with nothing. Inevitably, they began to cast covetous eyes on PUF.

Fifteen years ago they wouldn’t have had a chance. But recently the Legislature has created all sorts of new colleges across the state, each one with a defender in the House and Senate. A sample of what might happen to UT and A&M occurred last session: black legislators irate over A&M’s financial neglect of the predominantly black Prairie View campus made good their vow to thwart any attempted resolution of the construction issue unless A&M was required to provide for Prairie View.

No one wants the controversy settled more than UT and A&M. UT has even offered to take Prairie View off A&M’s hands (the Aggies, ever prideful, said no). The big schools desperately want a new fund to take the heat off PUF, and Bill Hobby has proposed doubling student tuition to provide the money. But some Republicans, including Bill Clements, have begun to wonder whether the whole idea of a dedicated fund makes good fiscal sense. Some colleges are actually losing enrollment; they don’t need more buildings, but if the money is there, they’ll spend it. The alternative—to let the Legislature decide the merits of each project—might actually work if the members didn’t engage in logrolling, which, alas, is where we came in.

The People’s Choice

Initiative and Referendum

Initiative and its sibling, referendum, are ideas whose time has come—and gone. The devices were dreamed up before the turn of the century, when state legislatures were so openly corrupt that even as confirmed a cynic as P. T. Barnum, then a member of the Connecticut assembly, professed shock at the way his colleagues accepted favors from railroads and other industries. Reformers believed that initiative (allowing the public to circumvent the legislature by proposing a law and voting on it at the polls) and referendum (using the same process to reject a law already passed by the legislature) would usher in the long-awaited millennium of honest government. Conservatives, though, had a different view: they looked upon the movement with horror, and President Taft warned that “the ultimate issue is socialism.”

Political reforms have a way of not living up to expectations, and initiative and referendum have proved to be no exception. Taft’s fears were so groundless that the staunchest advocate of initiative and referendum in Texas has been Bill Clements, not exactly a closet socialist. Clements proposed a state constitutional amendment authorizing “I&R,” as the issue is known around the Capitol, as part of his tax relief package last session. He envisioned voter ground swells for such items as prohibiting the Legislature from passing a state income tax. The governor pushed hard, but he couldn’t quite muster the two thirds of the House needed to approve submitting an amendment to the people. Had he succeeded in the House, there was more trouble ahead: senators jealous of their life-and-death power over legislation were adamantly opposed to anything that could allow the public to detour around the Legislature.

Clements pledged to call a special session and come back with guns blazing. But even before Billy Clayton’s Brilab troubles got the governor off the special session hook, word leaked out of Clements’s office that his ardor was cooling.

The governor continues to insist that I&R is near the top of his wish list for the upcoming session, but that may be face-saving puffery. Since last session a curious coalition has taken shape against I&R: it includes everyone from organized labor on the left to behind-the-scenes business heavyweights like Houstonians George R. Brown and Walter Mischer on the right. All the opponents are given to high-minded talk about how I&R defeats the purpose of representative government, but what they’re really saying is that—like lawyers who’d rather settle out of court than trust the whims of a jury—they’d rather deal with the known evil of the Legislature than roll the dice.

Conservatives were reminded that I&R is a double-edged sword when California, the same state that passed Proposition 13 and started the nationwide movement for property tax relief, almost adopted through initiative a punitive tax against oil companies two years later. The industry had to spend millions for a media blitz to beat it. Labor in Texas has taken that cue to let it be known that if I&R passes, it will immediately propose a corporate income tax. Probably it would fail—today—but the people opposed to I&R are the sort of folks who can take a long-range view, and they know that President Taft’s words might come back to haunt them. The likeliest prospect is that Clements will accept a watered-down version of I&R—one, say, that gives the Legislature a chance to act on its own before a proposal passed by the public becomes law—and expend his political capital on worthier subjects like redistricting.

Bottled Up

Throwaway Beverage Containers

For eons now Texas legislators have been arguing about bottles. For the most part the fight has been over what’s inside, but the passage of liquor by the drink in 1970 changed the focus to the container itself. Last session the Legislature quarreled for two days over the size of beer bottles; this session they will probably spend less time on a matter of considerably more interest to most people: litter caused by throwaway bottles and cans.

The Sierra Club—not exactly the Midcontinent Oil & Gas Association when it comes to lobbying clout—wants to cleanse the outdoors of this most common artifact of modern America. Rather than ban the can (their old rallying cry), they’re willing to settle for a deposit on every beverage container. Six states—three in New England, plus Michigan, Iowa, and Oregon—already have such laws, and sure enough, economics has prevailed and people want their money back.

But the odds are long against Texas’ becoming the seventh. The bottle bill is likely to get mugged in the dimly lit passageways of the legislative process by a gang of small but vocal interest groups, none of which fight very well alone, but which together can do a lot of damage. The glass industry doesn’t want to retool its machinery that makes nonreturnable bottles. Distributors don’t want the inconvenience of keeping up with deposits. Neither do retailers. Glassworkers worry that plant jobs will be lost. Aluminum producers fear that demand will drop. There is nothing to steer the bill through these dangers except someone’s memory of a bespoiled campsite or roadside or beach or park—and most legislators aren’t the outdoorsy type.

Ordinarily the bottle bill would be doomed to a quiet death in some obscure committee. But this time legislative procedure may work in its favor. Some legislators and bureaucrats are concerned about the state’s growing litter problem, though not specifically about throwaway bottles. If, as seems likely, there is an attempt to update the state’s flimsy litter laws, advocates of a bottle bill have a vehicle they can use to offer amendments. They may not win, but at least, to put it in legislative parlance, they will get a run at it. With some sophisticated lobbying for a change—phone calls to legislators from influential nature lovers back home—the Sierra Club might sneak through an amendment to prohibit detachable pull tabs. Even if they can’t ban the can, they could stop the top.

Waste Not, Want Not

Nuclear Waste Disposal

When a legislator begins an explanation of his own bill with the phrase, “all this bill does is . . .” it is generally time to lock up the women and children and keep an eye on the family jewels. That was the case last session with a bill that ostensibly did nothing but regulate the disposition of the radioactive refuse from uranium mining. Actually it did a lot more: it permitted low-level nuclear waste dumps in the state.

That bill died in legislative limbo after different versions passed the House and Senate, but a new and improved nuclear waste bill—identified as such this time around—will be back. Now the question is, who needs it? Chem-Nuclear Systems, Inc., for one—that’s a firm that envisions big bucks from operating waste dumps in Texas. But Chem-Nuclear is not alone. Texas generates a substantial amount of low-level radioactive waste, most from medical chemotherapy, some from new methods of logging wells in the oil patch. A nearby nuclear waste dump would simplify a lot of shipping and handling problems, since the only low-level disposal sites now operating in the country are in South Carolina, Nevada, and Washington State.

The reason a bill is necessary at all is that the feds require all nuclear waste dumps to be publicly owned (the state can lease the site to operators like ChemNuclear), but Texas law prohibits state agencies from owning land unless specifically authorized by the Legislature. The bill is the solution to this dilemma. Supporters of the legislation, including the state Health Department, warn that if Texas doesn’t do something, the federal government will step in to authorize and regulate waste dumps here.

Maybe they will. But the feds don’t seem to be giving the do-it-or-else lecture to anybody else. By passing the bill, the Legislature may end up making Texas the newest nuclear waste dumping ground for the rest of the nation. No doubt the lawmakers will insert a clause restricting the sites to accepting Texas-produced waste only, but that limitation would stand on shaky constitutional ground—judges of every ideological stripe frown on parochial restraints on interstate commerce. It might be worth the gamble to wait another two years (particularly since, if the gamble loses, there are worse fates than missing out on the headache of regulating nuclear waste dumps), but that isn’t likely to happen: there are few arguments more persuasive to legislators than the specter of a Texas industry, no matter how undesirable, being regulated from Washington.

Turning On the Tap

The Governor’s Crime Package

Crime is the perfect political issue. Nobody is for it, so an anti-crime package won’t make any enemies. Nobody can eliminate it, so no one expects a bill to work miracles. Recent Texas governors, predictably, have tilled this fertile political soil—crime and no new taxes were almost all Dolph Briscoe cared about—and Bill Clements is no exception. What makes Clements different is that his program is broader, better thought out, better supported, and more controversial than anything his predecessors have tried.

Clements has resurrected a few of the Briscoe staples (allowing wiretapping, but only in drug cases; permitting juries deciding on punishment to be informed about eligibility for parole; making oral confessions admissible), but he has also aimed at some long-neglected aspects of the criminal justice system. One is bail bonds, a notoriously corrupt area where the law protects the bondsman, not the public. Other laws—on shock probation, sexual abuse of children, and juvenile probation—need fine tuning. Finally, Clements wants to close one of the many loopholes the Court of Criminal Appeals seems to cherish: in an aggravated rape case, for instance, the court reversed the conviction of a man who never threatened the victim’s life in so many words, though he dragged her naked down a gravel lane.

The other major push in the crime field will come from Ross Perot’s anti-drug crusade. That package will contain everything from the new offense of trafficking in drugs, intended to get big importers (sale and possession with intent to sell are currently the most serious offenses), to a rather silly proposal designed to put head shops, which cater to the remnants of the sixties counterculture, out of business.

The Clements package will probably get most of the attention, though, because it will have well-orchestrated lobby and editorial support. Curiously, despite their obvious appeal, anti-crime bills in the past have had rough sledding in the Legislature. This is less attributable to a deep-seated reverence for civil liberties than to the fact that a number of legislators practice criminal law and are happy with the system as it is. Then too, the major law enforcement lobby groups—district and county attorneys, sheriffs, chiefs of police, and the police rank and file—are not the most effective lobbyists, and to make matters worse, they are always split, each group pushing its own bills. This time all four have signed on to the Clements program, but whether, for example, the police will work as hard to achieve bail bond reform as to pass wiretapping remains to be seen. This is not the first session for most of these bills, and it may not be the last.