In a nondescript industrial park in far-north suburban Austin, about 150 people are building spaceships. Covering one wall is a giant portrait of Wernher von Braun, the German rocketry pioneer. In the back, there’s a machine shop where engineers are turning out rocket engines. A giant video screen displays a real-time feed from the company’s engine test site in Briggs, about thirty minutes from headquarters, where more engineers regularly blast fire across the prairie.

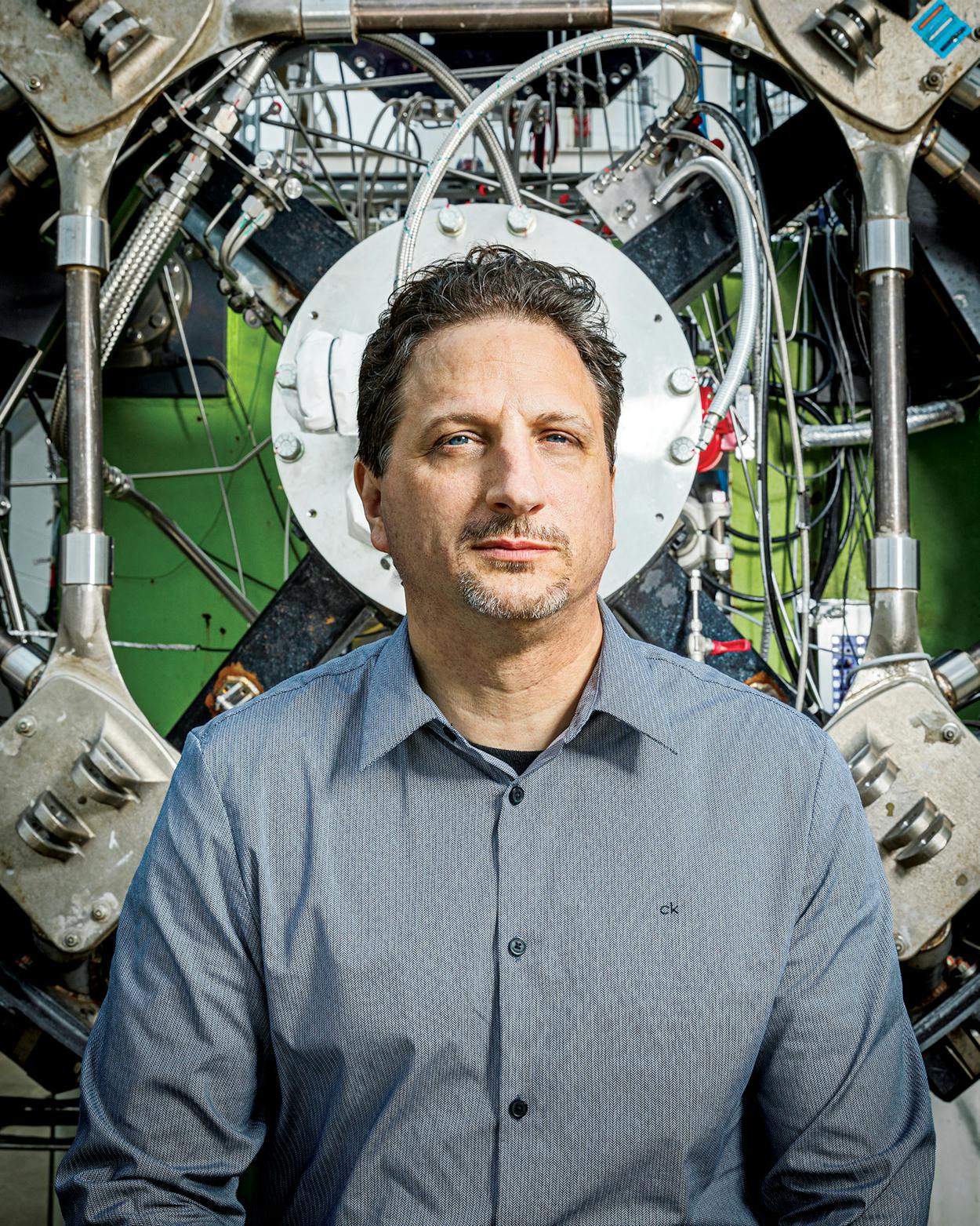

Both facilities are part of Firefly Aerospace, a maker of unmanned spacecraft and rockets for launching satellites. Tom Markusic, the 49-year-old founder and CEO, has worked for America’s largest public and private space ventures, from NASA to SpaceX. During a recent conversation at his Cedar Park office, the Ohio native opened up about his company’s roller-coaster journey to launch, the power of “New Space,” and why he’s doing it in Texas.

TEXAS MONTHLY: Your company’s tagline is “Making space for everyone.” What do you mean by that?

TOM MARKUSIC: That’s just another way of saying “New Space,” as opposed to heritage space, the NASA era. New Space is about dramatically lowering the cost and increasing the access to space.

TM: Texas has such a long history in the space industry, specifically in the NASA glory days. Can you contrast Old Space and New Space for me?

MARKUSIC: We try to be gentle and not say “Old Space.” We call it heritage space. I think “old” really shortchanges what it is; heritage is important. We’re very much interested in integrating things from the past to make our lives easier. So the foundation that’s been laid is important, but operationally we’re a lot different.

TM: How so?

MARKUSIC: Faster, cheaper is the big thing, and not being afraid to try different approaches.

TM: A layperson would look at Texas’s history with space and say, “There must be a lot of rocket scientists in Texas, so it makes sense to launch a company like Firefly here.” But is that actually why you’re in Texas?

MARKUSIC: Building a great company is not about drawing in a bunch of people who’ve done this sort of stuff before. It’s about drawing in the most talented people possible. Find the smartest, hardest-working, most passionate people you can, and if they don’t have space experience, that’s okay because they’re so good. They’ll learn, and they’ll pass the more experienced people very quickly. That’s the kind of company you’re trying to build in New Space.

TM: So you’re not hiring a bunch of NASA people.

MARKUSIC: Exactly.

TM: Why did you create this company in Texas, then?

MARKUSIC: When Elon [Musk, the founder of SpaceX] came and set up a rocket test site in Texas, I was the first long-term director of it, and I saw things about Texas that were very attractive. Texas offers a great economic and regulatory environment. Low cost of living. Austin has a very tech-focused culture. The environmental regulations are not onerous. Land rights are very free—what you can do on your land allows you to move quickly. Contrast that with California, which I experienced firsthand working for Virgin Galactic. I worked for NASA in Alabama, and I worked in Washington state for [the Jeff Bezos–founded] Blue Origin. I’ve been all over, and when it came time to start my own company, it was pretty self-evident that Texas was the place.

TM: I recently saw a stat that said SpaceX built its Falcon 9 rocket with almost $400 million, whereas there was a NASA estimate that it would cost $1.6 billion to build a similar kind of vehicle. Why is it so much cheaper for a private company to do that?

MARKUSIC: When you’re doing something in that heritage space way, you’re inheriting a lot of requirements that can drive cost up. It’s a very risk-averse framework. Many things in the government are like, “You just add money and a person. Here are the instructions—do this thing.” That type of approach is usually pretty reliable in getting the result you want, but it’s really expensive. And it’s usually undergirded by contractors who are disincentivized to make things at the lowest cost. With New Space, you’re spending people’s money; you’re not spending this amorphous blob of taxpayer money. That just pervades the whole culture.

TM: Let’s talk about how you got here. How does a person decide it’s time to start building spaceships?

MARKUSIC: I’m very interested in interstellar travel, and I’ve spent a lot of my life studying the underlying physics of that. I got a PhD from Princeton, where I studied plasma physics. At the time, fire-breathing rockets were something I absolutely turned my nose up at. I thought, “People already figured that out.” I was interested in the really far-out stuff, and that’s what I ended up working on for NASA and the Air Force early in my career. Developing space systems for military purposes, systems to take humans to outer planets, robotic exploration of outer planets. And then I met Elon.

TM: Who had just started SpaceX.

MARKUSIC: Yeah. NASA kind of pulled the rug out from the R&D stuff that I was working on because they wanted to focus on a new program called Constellation, which just wasn’t for me. So they gave me an opportunity to be a manager. I always like learning new things, so I thought I’d learn about management and how organizations work. I just dug into all the details of that. And at some point they were like, “Hey, there’s this crazy dot-com guy who thinks he’s going to build his own rocket. Why don’t you go out and see what they’re doing and see if there’s anything useful you can learn from them?” So I packed up all my management books and stuff that I was reading—you know, The One-Minute Manager or Who Moved My Cheese?—and I went to Kwajalein.

TM: That’s the chain of South Pacific islands where SpaceX was testing its Falcon 1 rocket.

MARKUSIC: Yes. And there I found a bunch of guys and women just sweating in T-shirts and drinking a lot and fishing and going between islands on catamarans and putting up this rocket. They were having bonfires and sleeping under the stars and all this stuff—and I was reading my sterile, spiritless management books. I’d been wearing a tie to work, with lots of paper pushers around me. And it became clear to me that the purpose of management books was to sell management books. And here were these people literally building a machine to go to space. I just hit it off with them, and eventually I was like, “Hey, can you hand me a screwdriver?” and I started helping.

TM: I love the image of a guy with a PhD working on a rocket with a screwdriver. Like, “We better tighten this down before launch.”

MARKUSIC: We ended up crashing three rockets there, and part of that was probably from lack of discipline. But it was a learning experience. There was just such a dramatic contrast between what we were doing out there and my real job. Elon was there pretty much full-time, and I was just inspired by his belief that it was all going to work perfectly. It was very clear that this guy expects, one hundred percent, that this thing’s going to launch and it’s going to be great. There’s something magnetic about that. These guys were charting an entirely new path to space, this lower-cost, higher-frequency access. As soon as I got back to the States, I got an offer to leave NASA and run SpaceX’s Texas engine-testing facility, in McGregor. My wife was eight months pregnant at the time, but it just felt right.

TM: But eventually you left SpaceX. Why?

MARKUSIC: After having worked for them for about five years and crawling through rockets and taking every little nut and bolt apart, I learned everything about launch vehicles to the point where I could design one myself. And by then it was clear to me that not only was SpaceX for real, but this whole New Space thing could be very real. So I thought I should try to help other companies, to further the movement. I went to Blue Origin and was there very, very briefly [for just two months]. SpaceX had been just brutal and fast-paced, and I thrived in that environment, but Blue Origin felt much more like a rich man’s hobby. It was a shock to my system, and while I was there, I got a call from Richard Branson, at Virgin Galactic, asking me to help get his spaceship going. So I left to develop rocket engines for him for about three years.

TM: What was the opportunity you saw to leave and start Firefly?

MARKUSIC: Everything in those companies was about going to Mars [and colonizing space]. But it was clear to me that there was a need for a smaller rocket to serve the market for launching a new generation of small satellites into low-Earth orbit. I came to this crossroads where it was like, “I know how to do this. If I had a group of people and money, I could build this machine. I know I can. Let’s go make a rocket company.” That was at the end of 2013.

TM: Speaking of money, who do you turn to when you decide you want to start building rockets?

MARKUSIC: I was able to put in $1 million. My two business partners put in comparable amounts. And then we started talking to friends and family and our professional networks—a few hundred thousand dollars here, a few hundred thousand there.

TM: But that doesn’t get you super far.

MARKUSIC: You start to spend serious money when you’re hiring and making stuff. I think we eventually raised $20 million that way, the hard way, in small increments. That’s what was consuming all of my time. And when you’re burning through more than $1 million a week, as we were, you’re always just racing toward the cliff. I pitched every venture capitalist in Silicon Valley in that period, but those folks are used to funding app companies that have, you know, five guys and some programmers in India or something. They have a low probability of success but also low initial funding requirements and a very high potential payoff. So the venture capitalists can make a hundred bets on those kinds of companies for the price of funding one rocket company, which is also super risky.

TM: Which is why it makes sense that billionaires like Bezos, Musk, and Branson are the type of people who start rocket companies.

MARKUSIC: Right. You have to have a backer who has a passion for space, the resources, and a broader vision.

TM: So what happened? The company was living hand-to-mouth, essentially. How did you break out of that cycle?

MARKUSIC: We didn’t. We encountered a perfect hurricane of circumstances. We had finally put together a $30 million investment deal. One investor was a European company, and one was an American individual. It was the summer of 2016, and then Brexit happened and sent shock waves through Europe, which made the European company back out. Around the same time, SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket blew up on the launchpad and spooked the American investor. We ran out of money. Firefly Space Systems went out of business.

TM: On a human level, here you were, literally building a rocket ship, and you had to shut it down. That must have been devastating.

MARKUSIC: Absolutely miserable. It reminded me of the story of life—you know, you come in by yourself, you go out by yourself. In the end, it was just me sitting down in bankruptcy meetings. The hardest part was laying off 160 people—letting all of those people down— and letting investors down.

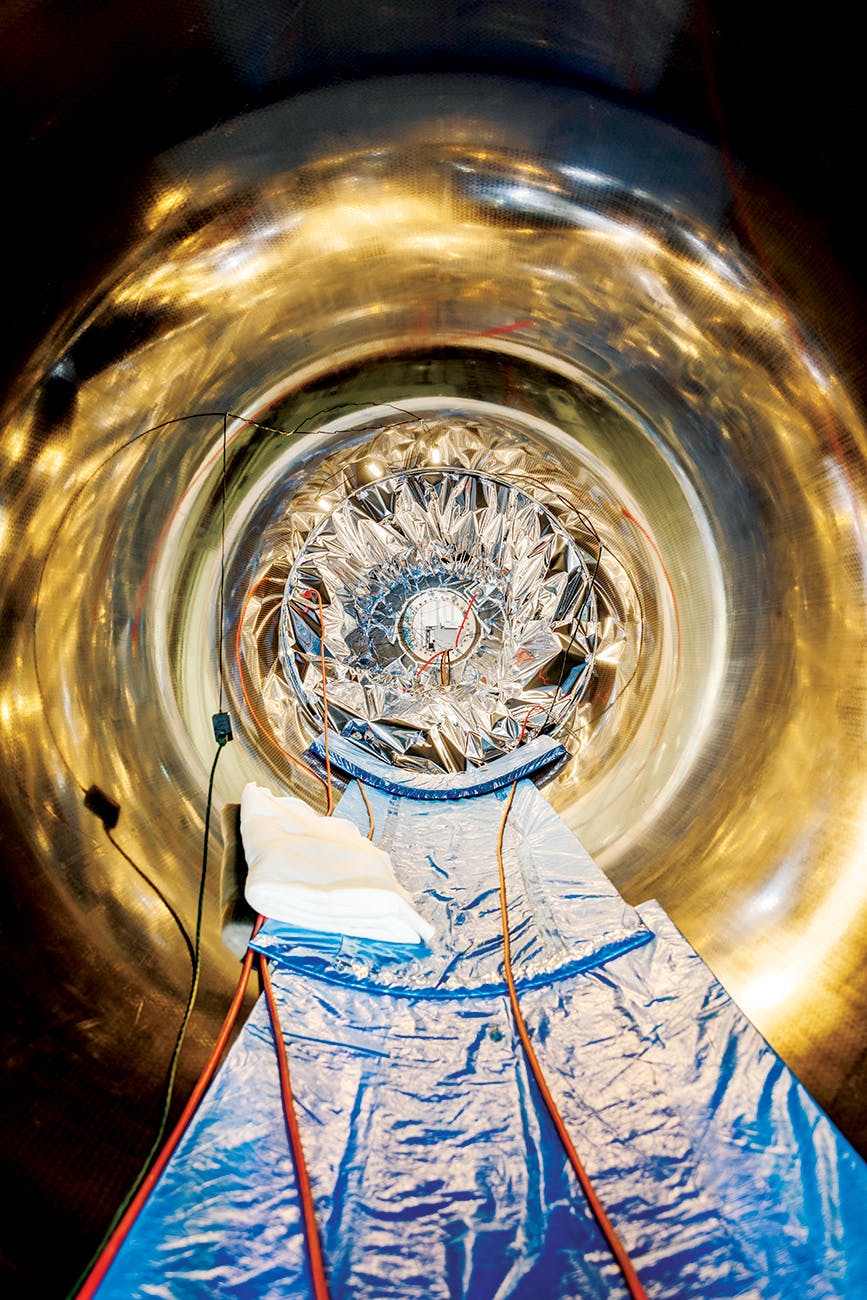

TM: What’d you do with all the stuff? I mean, there were rocket parts being built here. What happens to a partially built rocket that no longer has a company that’s building the rest of it?

MARKUSIC: That was the second-hardest part, looking at all this stuff and thinking that potentially somebody was going to drag it off and cut it up and sell it for scrap metal. So you lock the doors. I still had this office space that whole time and still had the test site in Briggs. I was actually coming in here to work. It was just me, alone, and the rocket parts.

TM: What were you working on?

MARKUSIC: It became about getting up every day and saying, “What am I going to do to try to turn this around, to bring it back?” And then, you know, things eventually happen.

TM: Like what?

MARKUSIC: We had learned a lot, and now I had an opportunity to design the absolute right rocket. If we had completed the first Firefly Alpha rocket, it would have been much less competitive than the second generation we’re building now: it was too small by half; the payload capacity was not optimal for the kind of satellites it would take up. I might have had us on a path to long-term failure anyway. So I started redesigning the rocket. The other thing that happened is that I met Max Polyakov, a Silicon Valley entrepreneur who’s figured out lots of different ways to make money on the internet. Max saw the stories of us going down, came out here and bought the company’s assets, and we relaunched as Firefly Aerospace six months after we shut down.

TM: Recently there was news that you would be building a factory on Florida’s Space Coast and launching at Cape Canaveral—and you previously announced you’d be launching at Vandenberg Air Force Base, in California, as well. Meanwhile, there are several rocket-launch sites in Texas—SpaceX has one near Brownsville, and Blue Origin has one near Van Horn, in West Texas. Why not launch closer to home?

MARKUSIC: It has a lot to do with what you’re going to fly over when you launch. You want to be in a place where, if your rocket fails, it’s not going to damage property or people below it. For orbital launches, being near the Gulf is just not as good an option as being near an open ocean. If you launch over the Gulf, you’re going to have to do some evasive maneuvers to go around islands like Cuba, and that wastes rocket fuel. It’s also just easier to use an existing facility. Part of the game here is time and money. There’s a pool of people talking about going to space, and it’s really hard to tell who’s real and who’s not real. So it’s super important to get there and show people you’re real as soon as possible. Look at SpaceX. They’ve been using government facilities, and now that they’re established, they’re building their Brownsville facility. I could see us building our own launch site one day, but right now I’ve got to pick our fights.

TM: Because small satellites orbit closer to Earth than traditional satellites do, they can transmit data to us more quickly. Why is that such a big opportunity?

MARKUSIC: I like to say that space is the next frontier in the information revolution, in both collecting and disseminating information. Take Earth imaging, for example: from low-Earth orbit, you can track how much iron ore China has or deforestation or how many cars are in a mall parking lot at any time. That’s incredibly powerful and valuable information. There are just unlimited use cases.

TM: So we’ll basically be getting persistent, high-resolution images of the whole planet?

MARKUSIC: It depends on what you want and how frequently you want it. And what region you’re looking at. I mean, we can talk about real-time stuff—say, following your girlfriend, watching where her car is driving from space.

TM: That’s creepy.

MARKUSIC: I just mean that it’s possible. Then there’s the ability to access markets that are closed. You know, [nearly half] of the people in the world don’t have internet. Giving them access could help lift them up. It’s easier to beam down widespread broadband internet access using satellites than to lay terrestrial cables and fiber. In many cases, it’s faster internet, too. I’ve had people from the biggest financial institutions in the world in here, in their Italian leather shoes, saying, “If you can get me data from India to New York five milliseconds faster than it can go through a fiber-optic cable, it’s worth $250 million to me”—because over fifty percent of trading is high-frequency trading. There’s just so much that’s going to happen. The perception that space exploration is all, like, “one small step for man” type of stuff is not really what’s going on. It’s all a big financial play, which is ultimately what it should be. We’re Americans. We’re a business. We should be about making money. Doing other things like going to the moon is icing on the cake.

TM: Can you paint me a picture of where Firefly goes in the future? Are small satellites an entry point into a much wider space play: manned interplanetary travel, things like that?

MARKUSIC: One thing I would like is for us to become a parts supplier. A big reason this has all been so expensive for us is because I’ve had to develop my own rocket engines, my own valves, all these things. You want to start a rocket company? Here: you can buy rocket engines out of my catalog. I’ll sell you the parts. So the barrier to entry for future companies would go way down because you don’t have to create these technological miracles to get your company started. In the past, parts were unbelievably expensive because they were being primarily sold to the government. If you wanted to buy a space-shuttle main engine, it was tens of millions of dollars. But if you could buy rocket engines for a couple of hundred thousand dollars from this company in Austin? It would totally change the economics.

TM: You’ve announced that you will launch a rocket by the end of this year. Is it going to happen?

MARKUSIC: People make too many promises in the world, and I’m not a promise type of person, but I can tell you that everyone in this company is working toward 6:30 a.m. on December 16, 2019. And we’re giving it hell.

TM: Okay—be honest. How much of what you do is because rockets are just cool?

MARKUSIC: I’m a Christian guy. I definitely believe in Providence. I believe there’s a God who built me to do this kind of stuff. And if you’re doing what you’re built to do, it’s just naturally awesome, right? It is awesome.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

This article originally appeared in the July 2019 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Getting to Liftoff.” Subscribe today.