This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

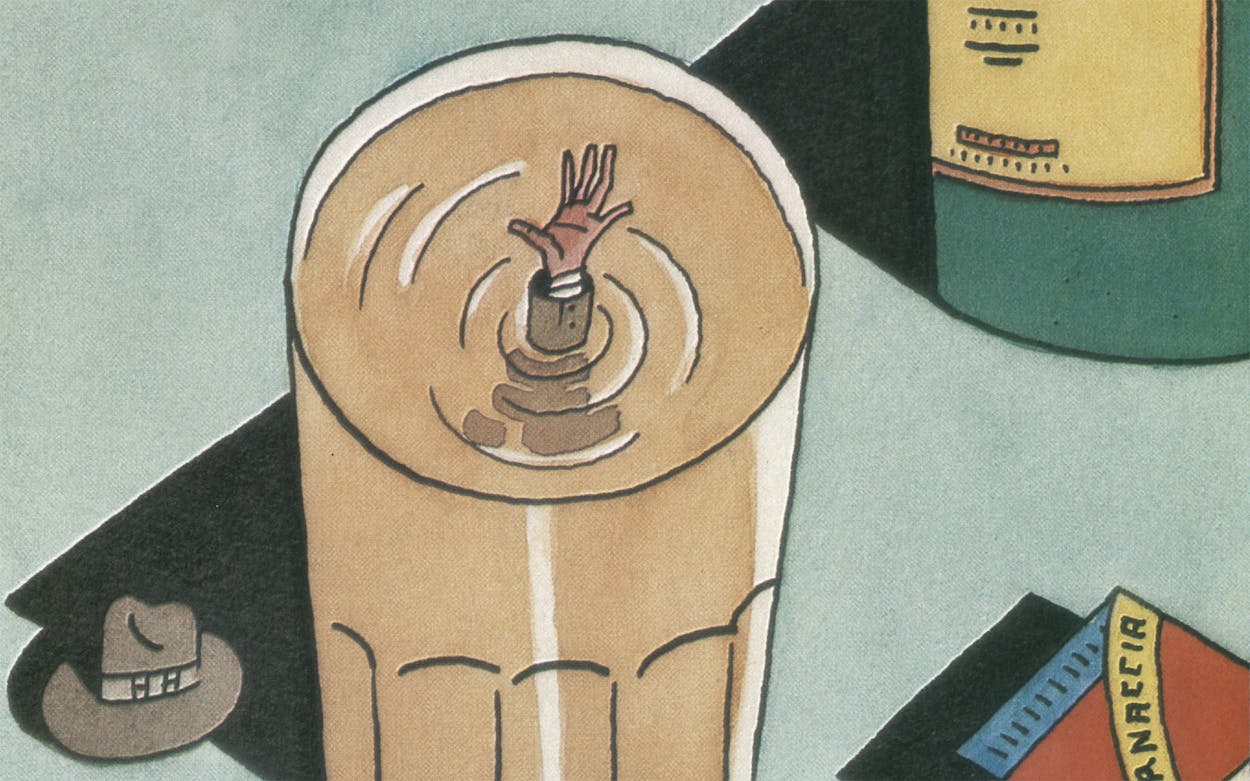

Over the last five years alcoholism has become what would seem to be a contradiction in terms: a popular disease. It would be nice to think that diseases are absolute entities, but like everything else, they are subject to the dictates of fashion and circumstance. Hysteria became popular during Freud’s time because it responded well to psychoanalysis—which does not mean there was no hysteria before Freud; it does mean there was no point or profit in diagnosing it until a treatment existed. Psychiatrists have suggested that behavioral therapy is having the same effect on alcoholism.

The key event in the popularity of alcoholism was Betty Ford’s announcement in 1978 that she was entering the Long Beach Naval Hospital to deal with her drinking problem. A string of celebrities stepped forward to announce that they too were recovering alcoholics, and now it has become commonplace for publicists to inform the press that their clients are entering treatment.

Fashion and sociology aside, alcoholism is a real and devastating problem. The Texas Commission on Alcoholism estimated that state services and other costs related to drinking totaled $5.4 billion in 1984. Thirty-seven per cent of fatal motor vehicle crashes, 26 per cent of fire fatalities, 44 per cent of fatal falls, and 30 per cent of homicides are alcohol-related in Texas, though it is impossible to say how many of those accidents involve true alcoholics. There are no statistics that reflect the suffering that people who live with alcoholics endure.

What Is an Alcoholic?

It is fairly common for anyone who drinks to worry about whether he will ever become an alcoholic, and that anxiety is compounded by a general lack of information about the disease. Myths and folklore abound, but when you start trying to determine exactly what an alcoholic is, the old definition—the man who drinks more than his doctor—is still about as good as any.

Part of the reason we know so little about alcoholism is that it was not pronounced a disease until 1956, when the American Medical Association bowed to pressure from Alcoholics Anonymous. The AMA made its decision on the grounds that the condition is chronic (it won’t go away if left alone), contagious (it affects everyone around the alcoholic), progressive (it has stages that can be described and predicted), primary (it isn’t just the symptom of an underlying disorder), and fatal. Before 1956 very little money had gone into scientific research, because most people thought that the cure for alcoholism was obvious—don’t drink. It wasn’t until the seventies that significant amounts of public money became available for research. Even today doubt lingers; only 50 per cent of medical academicians agree that alcoholism is a disease.

Among professionals in the field of alcoholism, working definitions range from the all-inclusive to the narrow. Some doctors diagnose alcoholism if a patient admits to one occasion during the past year when he drank as few as seven drinks. The Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test, a standard diagnostic tool, says that anyone who has ever attended an AA meeting is an alcoholic, and many diagnostic instruments give an alcoholic’s score to anyone who has ever quit drinking. That is as fallacious as the assumption that only obese people diet.

A more conservative and sensible approach is that of Arthur Tarbox and Gerard J. Connors, assistant professors at the University of Texas Medical School at Houston, and Louis A. Faillace, acting dean of the school. In their outpatient program for problem drinkers, they use physical dependency to identify alcoholics. For instance, if a patient has the shakes in the morning (tremulousness is the first sign of dependency), then he is an alcoholic. If he doesn’t, then he is a problem drinker.

When pressed for a definition, most professionals say that an alcoholic is someone whose drinking causes family, professional, or spiritual problems. That sounds practical, but individual cases always raise some reasonable question (particularly in the alcoholic’s mind) as to which came first, the drinking or the problems. Unless he is in advanced stages of the disease, the alcoholic must ultimately diagnose himself.

But how can he know? One of the early signs to watch for is an increase in tolerance. A person who finds that he can drink larger and larger amounts before getting drunk should probably show caution. He should also take care if he becomes preoccupied while waiting for his first drink or if he finds himself slugging drinks—knocking them back faster than his friends. Other early symptoms include surreptitious drinking, blackouts, defense of his drinking with excuses, feelings of guilt, and an unwillingness to quit drinking when others do.

How Alcohol Works

Though no one completely understands how people become alcoholics, what happens when someone drinks is fairly clear. Alcohol is absorbed directly into the bloodstream through the lining of the stomach and through the small and large intestines. The alcohol is then carried along to the brain, where it has an anesthetic effect directly proportional to the amount of alcohol in the blood. That, of course, is determined by how fast the person drinks and by how fast his body metabolizes and detoxifies the alcohol. A man who weighs 150 pounds can burn about one drink an hour (the typical drink being a twelve-ounce beer, four ounces of dry wine, or an ounce of hard liquor) with little or no effect. Two drinks in quick succession take the blood alcohol of the same average drinker up to 0.05 per cent, the level at which most people begin to relax and feel free of inhibitions.

But as more alcohol enters the blood, it begins to affect voluntary motor action. At 0.1 per cent, which constitutes legal impairment in Texas, speech, walking, and hand and arm motions become clumsy. At 0.2 per cent, the entire motor area of the brain is affected as well as the part of the brain that controls emotional behavior. Thus, in addition to staggering and slurring words, the drinker may become boisterous, angry, or maudlin. At a concentration of 0.3 per cent, most people pass out. At higher levels, the lower brain, which controls breathing and heartbeat, is depressed and the drinker dies.

Because heavy drinkers build up a great tolerance for alcohol, the drug does not affect them in the same way that it does the casual drinker. It is not unusual for alcoholics who maintain steady blood alcohol levels of 0.25 per cent to be able to function in a normal manner. Over time, however, that level of alcohol can cause major damage to the body. It kills off brain cells (resulting in a loss of short-term memory and the ability to concentrate), causes vitamin deficiencies (alcohol is high in calories but devoid of nutrients), and leads to cirrhosis of the liver, which is the fifth-ranking cause of death for middle-aged men in the U.S.

As the disease progresses, the physical effects worsen. Nerve damage, dementia, heart disease, and respiratory infections are common. Bones and muscles weaken, and hormone production slows down. Eventually it is simply a matter of which organ fails first. Those are the effects only of long-term, heavy abuse, though. The good news is that in most cases the effects of heavy social drinking go away after three weeks of abstinence and that a person must be physically dependent on alcohol for at least five years to suffer permanent cognitive damage.

The Biochemical Roots

According to the most recent scientific research, there are two distinct types of alcoholic. One type, the genetically predisposed alcoholic, develops the disease as early in life as his mid-twenties. The other, who is given to anxieties and phobias, drinks for years before becoming chemically dependent.

Normally, enzymes in the liver break alcohol down to acetaldehyde, a toxin that is then further broken down and eliminated through the lungs and kidneys as carbon dioxide and water. In some people, however, acetaldehyde becomes what are called TIQs (tetrahydroisoquinalines). So far TIQs have been observed only in the test tube, but some researchers think that they are addictive substances formed by some genetic quirk in certain people. The researchers believe that TIQs fill in for the brain’s normal supply of endorphins, which relieve pain and impart a sense of well-being. The genetic alcoholic thus becomes dependent on alcohol to feel good, for drinking is the only way he can keep TIQs in his system. Without alcohol, he feels pain and depression; with it, he feels relief. Though the relationship between alcoholism and TIQs is not yet completely clear, researchers have found that laboratory rats bred to avoid alcohol become heavy drinkers after their brains are injected with minuscule doses of TIQs.

If the TIQ theory proves accurate, it would explain how alcoholism is passed from one generation to the next—a phenomenon for which there is already substantial evidence. Studies published in Denmark in 1973 showed that the sons of alcoholics, though removed from their parents at an early age and placed in nonalcoholic foster homes, were still four times more likely to become alcoholics than other children were. In another study, conducted by Marc Schuckit of the University of California at San Diego, sons of alcoholics produced higher levels of the toxin acetaldehyde after drinking the same amount as a test group. Yet another study showed that after one drink, alcoholics’ sons had noticeably different brain waves from those of the sons of nonalcoholics.

A second theory accounts for alcoholics who show no genetic predisposition and who drink for years before becoming addicted. According to the theory, prolonged exposure to alcohol fundamentally alters the way in which ions, which transmit electrical messages that result in thought and behavior, move between brain cells. Once that change has occurred, the alcoholic must continue drinking in order for his brain to keep working comfortably. If he stops drinking, his brain can’t snap back to its old way of functioning, and thus those basic messages become scrambled. The effect, which is thought to result from many years of heavy drinking, can sometimes be reversed, depending upon the age and physical condition of the alcoholic.

Alcoholics Anonymous

Alcoholics anonymous was founded in 1935 by New York stockbroker William Griffith Wilson and Akron physician Robert Smith. Wilson knew about Carl Jung’s belief that in rare cases alcoholics recovered after having a spiritual or religious experience that resulted in a fundamental change of personality. Wilson had also read William James’ Varieties of Religious Experience and knew that people, particularly alcoholics, tended to have those conversions at moments of greatest despair. Thus he set out to create an organization that would treat alcoholism through faith. Since the thirties—when drunks were still being turned away by the medical profession and excluded from public hospitals—AA has helped millions of individuals. The national office in New York does not keep membership records, but it is estimated that there are 1.5 million members in the U.S. today.

Explaining how Alcoholics Anonymous works is a matter of rationalizing the irrational. Under the auspices of medicine, AA treats alcoholism as a spiritual problem. The first article of faith that members must accept is the “disease concept” of alcoholism. If an alcoholic believes that he is suffering from an incurable fatal disease, then he can stay sober—just as a Christian can follow the straight and narrow if he believes in fire and brimstone.

AA functions like a religion in other ways as well. It provides a social structure, a way of interpreting one’s life, and precise rules as to how to live. In AA there are twelve steps to sobriety, which function like the ten commandments. The first step (“We admitted we were powerless over alcohol—that our lives had become unmanageable”) is called the surrender. The second step (“We came to believe that a power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity”) completes the surrender and replaces alcohol with another power—God or the power of the group or any other larger power that the alcoholic chooses.

Gregory Bateson, an anthropologist and learning theorist, has explained AA’s steps in terms of symmetry and complementarity. Bateson says that the advanced alcoholic sees himself in a symmetrical struggle with the bottle. The only way he can prove he isn’t weak (not an alcoholic) is to drink. Yet drinking makes him more dependent and weaker still. Caught in that double bind, he gives up all hope. The steps set out by AA provide an escape from the circular struggle; they require the alcoholic to take inventory of the harm he has done other people, make amends for that harm, and help other alcoholics. The steps lead him out of his own struggle and back into the world.

The good thing about AA—and this cannot be overstated—is that it works. Quite often it works when nothing else will. The problem, however, is that AA has narrow views about alcoholism and perpetuates its own set of myths. AA says that once an alcoholic, always an alcoholic, but in fact many people drink symptomatically in times of disappointment or despair, then quit or go back to asymptomatic drinking when their lives change. AA sets itself up as the only path to sobriety, but many alcoholics will not join AA, for the same reasons they wouldn’t join the Baptist Church or the Elks Club, and many people who abuse alcohol are not alcoholics. Occasionally you will hear family members complain that AA is as addictive as alcohol and that they now see their alcoholic no more than when he was spending time in bars, but more often you hear them thanking God for AA.

Traditionally AA held that a drunk had to hit bottom before he could get help, that any assistance from the outside only prolonged the ordeal. That philosophy started to change approximately five years ago when Vernon E. Johnson, a retired minister and leading light in alcoholism treatment circles, asserted that it was better for family members to intervene in the early stages of the disease, before the alcoholic had lost everything. By “raising the bottom,” AA essentially started to recruit, and its membership is now much younger, larger, and more middle-class. Since 1979 the number of AA groups in the U.S. has increased by 40 per cent.

Most people in AA say that alcoholism is a spiritual disease that results from living in a materialistic world. That would be one explanation of why people tend to drink more as they become more affluent, and it would also explain why joining AA, like owning a BMW, has become a sign of upward mobility. In an age of science and religion, AA has become an acceptable—even racy—way to get religion.

Anyone who decides to join should remember that not all groups are alike. There are special meetings for corporate executives, gay men, lesbians, and doctors, and the emphasis on religion varies from group to group. It makes sense to shop around.

Getting Treatment

Because Texas, the third most populous state, spends the least amount of public funds on the prevention and treatment of alcoholism, most problem drinkers end up seeking help in the private sector. Most private programs, however, are affordable only for wealthy people or members of group insurance programs. Low-cost options are few; they include committing oneself to a state mental institution, going to a Salvation Army treatment center, or getting on a waiting list for one of the state’s Mental Health and Mental Retardation facilities. Texas also has an assortment of halfway houses, VA clinics, and church-sponsored programs, but those vary drastically from city to city.

In the private sector, treating alcoholism and drug addiction has become a thriving industry. The Texas Commission on Alcoholism reports that there has been a significant increase in facilities within the last five years. In addition to programs in private psychiatric hospitals and clinics, two rural recovery centers near Kerrville—La Hacienda and Starlight Village—are well-known institutions in the world of alcoholism. In San Antonio, Raleigh Hills runs a 28-day residential program for adults, and there are Brookwood Recovery Centers (formerly Lifemark Recovery Centers) scattered throughout Texas. All of those private programs are AA-based. If one wishes to avoid the AA approach to treatment, the only real alternative is the Schick Shadel Hospital between Dallas and Fort Worth, which uses chemical and electrical aversion therapy in its 14-day, $9000 program and estimates that it has a 65 per cent success rate. Schick Shadel, which was founded in 1935, has the oldest private treatment program in the country.

Going to a residential treatment center for alcoholics is a good bit like going to an emotional boot camp. It is an experience designed to break, then make the patient. Most programs (including those housed in psychiatric hospitals) last 28 days and require that family members participate in the therapy at some point. Fees range from $7000 to $10,000, but they are usually covered by group insurance policies. Because so many people have group insurance and because treatment centers are in business to make money—not to maintain the social order—the exclusive sanatorium is something of a myth today. Anyone who can pay can go to the Betty Ford Recovery Center in Palm Springs, for instance, and be admitted regardless of how much or how little he drinks. People from all walks of life live and work together on intimate terms at residential centers; indeed, part of a patient’s therapy is to learn that he is a drunk just like everyone else and has no special dispensation to drink. Counselors (usually recovering alcoholics) indoctrinate patients in the principles of Alcoholics Anonymous, and patients at most centers pledge to attend ninety AA meetings in the first ninety days after they finish the residential program.

The first step in treatment is usually detoxification. If the patient is chemically dependent, he is put on a minor tranquilizer and an anticonvulsant to ease him through three or four days of withdrawal. The drugs prevent the shakes, nausea, and headaches that usually accompany his first alcohol-free days. In more serious cases the alcoholic has vivid and terrifying hallucinations, his heart races, and he sweats profusely during withdrawal. This is known as delirium tremens, and it is properly considered a medical emergency; 20 per cent of those who go untreated die. But thanks to medication, detox is a breeze for most patients.

At the treatment center where I observed a four-week program, the day began at six-thirty, when a nurse walked down the hall and knocked on patients’ doors. There were two patients to each room, which resembled those in a dormitory. Patients did exercises before breakfast in the cafeteria. After receiving medication at the nurses’ station, they went to “meditation,” a short service of inspirational readings from an AA favorite, The Twenty-Four Hour Book. At nine a staff member lectured on some aspect of the disease concept of alcoholism, then at ten the forty or so patients divided into two groups for peer evaluations that lasted until noon. After lunch, patients met in small groups with counselors to whom they had been assigned for the duration of their stay. From three to five, two patients told their life stories. Patients were allowed to go for walks on the grounds if they signed the nurses’ log and went with another patient, but they were not allowed to read anything other than the daily newspaper and assigned materials, and they were not allowed to stay in their rooms except to sleep. Families could visit on Wednesday nights and Sunday afternoons, and after the first five days patients could make two telephone calls a week.

The key events in each day and in each patient’s stay are the telling of his “life story” and the subsequent evaluation by his peers. Telling his life story consists of going before his peers to explain how he became an alcoholic and what alcohol has done to him. Since he is urged to tell everything he feels guilty about, the life story is much like a public confession.

There are two rationales for the life story. According to one, alcoholism is a guilt-based disease. Because about half of all alcoholics come from alcoholic homes, which have a high incidence of incest and domestic violence, they are likely to carry a burden of familial guilt. Regrets about their own behavior only make the burden heavier. By telling his story, a patient can relieve some of the guilt, and by listening to the others, he learns that everyone has his own secret.

The second rationale is that alcoholics are incapable of seeing what alcohol does to them, because they have developed a massive blind spot with regard to their drinking. In AA circles the inability to admit the power of alcohol is known as denial. It prevents the alcoholic from seeing his drinking as the source of his problems; instead he blames himself. He associates the euphoric effects of drinking with alcohol, which he believes to be good, and he sees the inevitable dysphoria as a product of his lack of control. That distorted perception pervades his life.

When the alcoholic tells his life story, his blind spot is revealed, since the other alcoholics present have done all the same things and used all the same excuses and rationalizations. Everyone takes notes and writes letters that night to the storyteller, which are read aloud on the following day in peer evaluation. The group sits in a tight circle, with the patient who is being evaluated in the middle. To maximize his exposure, he is required to go from person to person, take their hands, and look into their eyes before they start to read. It sounds hokey, but to participants it is very affecting, very real, like watching some sort of drastic emotional surgery. Invariably the patient is reduced to tears, and ideally he is brought to the point that he surrenders and takes the first step in Alcoholics Anonymous: he admits that he is powerless over alcohol and that his life has become unmanageable.

Are residential treatment programs worth the thousands of dollars they cost? It’s hard to say. According to George E. Vaillant’s The Natural History of Alcoholism, a landmark study published in 1983 by Harvard University Press, residential treatment does not significantly alter the course of the disease. The 65 per cent improvement rate cited by most centers means only that 65 per cent of their patients are doing better eighteen months after completing the program than they were one month before they entered it. Because patients don’t seek help until they have reached a state of crisis, that amounts to comparing their worst possible episode with an arbitrary point eighteen months later. A more accurate figure for true recoveries is probably 25 per cent—not much higher than the 20 per cent rate of spontaneous remissions. “Alcoholics recover,” writes Vaillant, “not because we treat them but because they heal themselves.”

That doesn’t mean that alcoholics shouldn’t be treated, but I wouldn’t recommend residential treatment until all other alternatives had been exhausted, and I definitely wouldn’t go to a private treatment center for an evaluation to decide if I was alcoholic. The vested interest that treatment centers have is obvious: they don’t make money unless they keep their beds filled. I would, however, consult my family physician, and if I needed detoxification, I would ask him to check me into a hospital and handle it as he would any medical problem. Then I would consider going to AA or, as an intermediate step, enrolling in an outpatient program at a treatment center (centers are usually listed in the Yellow Pages). Such programs typically last four weeks, meet in the evening, and cost about $2000.

One of the most interesting outpatient programs is that offered in Houston at the University of Texas Medical School, where Arthur Tarbox and Gerard Connors treat problem drinkers who are not physically addicted. The first step in their program is to have the participant keep track of when, where, and how much he drinks, so he can become aware of his drinking patterns. According to Tarbox and Connors, most of their participants are horrified when they realize how much they consume (twenty or more standard drinks a week puts someone in the upper 12 per cent of drinkers, qualifying him as a heavy social drinker). Then the participant learns about blood alcohol levels so that he knows what each drink does to him. The point is not to make him quit drinking but to make his drinking patterns a matter of choice. Tarbox and Connors teach participants how to relax, how to refuse a drink, and how to plan alternative activities during those hours when they drink the most. Participants are encouraged to plan days of abstinence, but those who are determined to drink are urged to decide on a time, arrange transportation, and take proper precautions. Based on interviews at one, three, six, and twelve months, some participants have shown a significant positive change.

More often than not, the person who recognizes the problem is not the alcoholic but a member of his family who wants to know what to do. That is a much harder question, and there aren’t any good answers. I would try Al-Anon, a support group for the families of alcoholics, if for no other reason than to talk to people who have the same problem. I would certainly try to get the alcoholic into treatment before letting him do permanent damage to himself or someone else. Al-Anon recommends that those close to alcoholics try not to blame everything on the drinking and suggests that they concentrate on living their own lives and making themselves happy without the alcoholic.

- More About:

- Health

- TM Classics

- Longreads