This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Smoke Glass Trail is an unlikely name for the last frontier. But in a Texas without rampaging Comanches and a train-robbing Sam Bass, Smoke Glass Trail will have to do. It’s a smooth, white cement street that snakes through fields of gravel, weeds, and newly planted grass in the very farthest reaches of far North Dallas, in a development called Bent Trail. It begins near a cluster of lavishly decorated model homes, sweeps through a stretch of flat, empty land, passes a row of brick houses—some vacant, some occupied—and abruptly stops at a curb thick with dried mud, where a prairie begins its run to the west. People live in those last houses on Smoke Glass Trail, settlers in $120,000 homes.

To the south, for fifteen miles along Preston Road, lie neighborhoods that have been spiraling northward for a hundred years. Close in, near the heart of Dallas, there’s the artsy old Oak Lawn section, the moneyed environs of Highland Park and University Park, and a miles-long cluster of middle-income homes separated by big, tree-shaded lawns where children kick soccer balls, men mow the grass, and teenagers wash their cars. Farther north, starting about where LBJ Freeway splits the city into North Dallas and close-in Dallas, the yards begin to shrink and even disappear. In brick-walled pockets all along Preston Road people live in two-story houses jammed together with but a few feet of space between them and a line of shrubs in place of a lawn—no backyard barbecue grill, no grass to walk barefoot on in the cool of a summer’s evening.

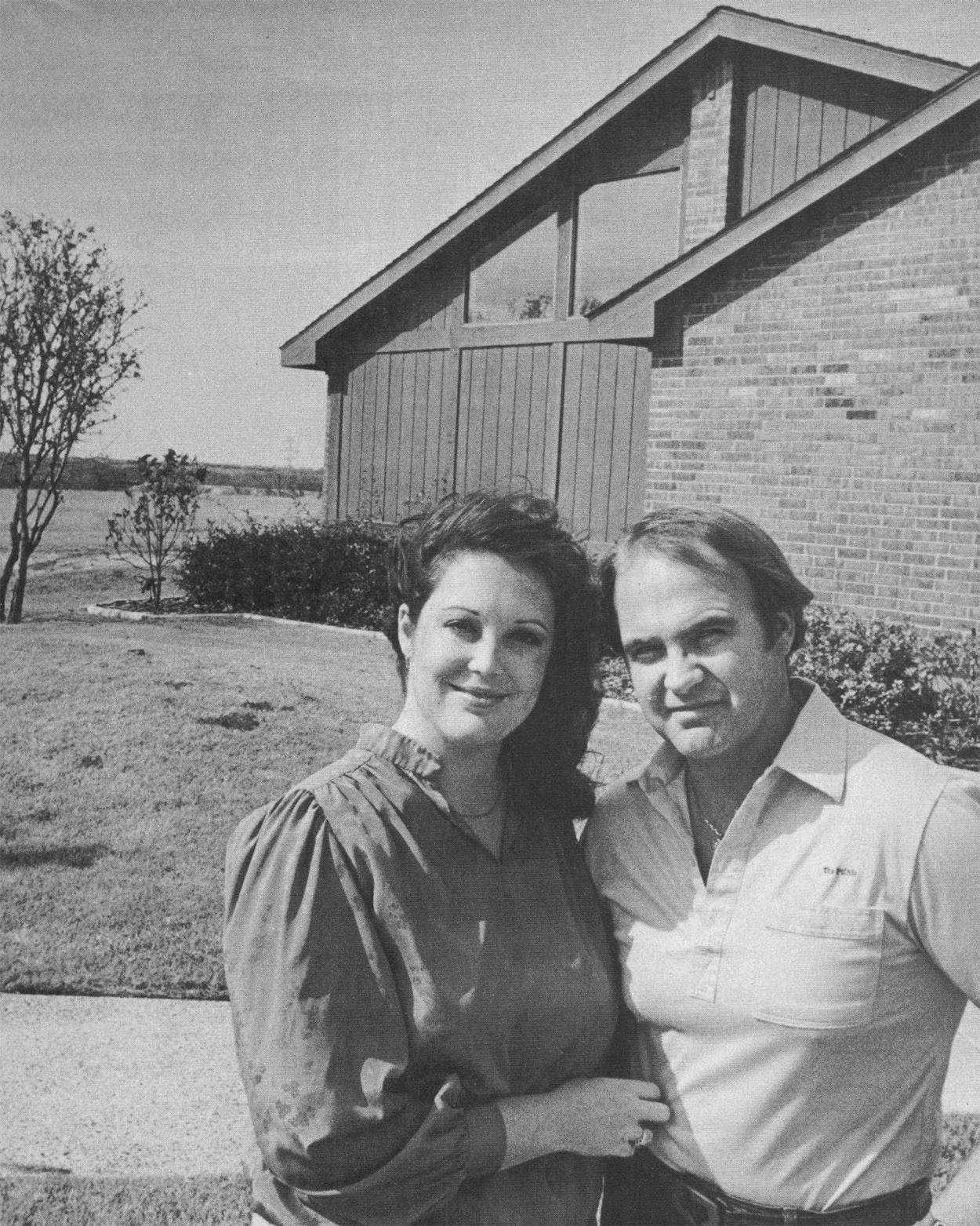

When Preston Road begins edging toward Plano, its six lanes narrow to two, the speed limit shoots up to fifty, and the streets aren’t even on the Dallas city map any longer. It is here, at the northernmost tip of Dallas, that you see the billboard on the east side of Preston: J. STILES IN BENT TRAIL. A quarter-mile farther lies the Bent Trail entrance, marked on the left and the right by two shimmering water gardens that cost $300,000 to build and that spill nearly four million gallons of water each day across silver letters that spell out “Bent Trail.” They’re impressive, these slick blue water gardens—they impress couples like Loren and Susan Sutherland, two Californians who were driving along Preston one day last May looking at houses. They saw the water gardens and they were hooked. Bent Trail felt rich, it felt expensive. Today, the Sutherlands live in the last house on Smoke Glass Trail—the last house in Dallas.

Just a scant three years ago, the land their house is on was a maize field owned by a wealthy Dallas family. There were no $230,000 custom homes on it, just a small house where the land’s only resident, a tenant farmer named Buddy Kimball, lived. In May 1979, real estate broker Sherwood Blount negotiated its sale to developer Jerry Don Stiles for $6 million (see “Sherwood Blount’s First Million,” TM, October 1979).

“It really is incredible, isn’t it?” Stiles asks rhetorically as he sits in his office a mile north of Bent Trail, just far enough north that it’s in the city of Plano. “May of ’79, I remember as if it were yesterday.”

First Stiles got the land zoned—46 acres high density residential, the rest single-family—and then he sold the high density portion to three apartment and condominium developers for $5.6 million. In January 1980 he purchased 50 acres at the southeast corner of Bent Trail from Charles Lloyd, an adjunct professor of religious studies at SMU, for a hefty $67,500 an acre. The tract was worth the price, for it gave Bent Trail prestigious Preston Road frontage. The water gardens were put up, the maize field was cut down, storm sewers were put in, electrical cable was laid, streets were paved. The development’s name was inspired by Bent Tree and Preston Trails, the two most desirable far North Dallas developments—home to such notables as ex-mayor Bob Folsom and Jerry Don Stiles. In November 1980 Stiles sold 190 Bent Trail lots to about 25 Dallas builders, holding back 170 for his own company. A few months later, he purchased 40 more acres to the north of Bent Trail. In the spring of 1981, model homes were completed, Open House signs were posted, and full-page ads proclaiming Bent Trail’s arrival appeared in the Morning News and the Times Herald.

Loren and Susan Sutherland arrived in Bent Trail with their Lyons moving van, a Datsun 280-Z, and an Olds Cutlass on July 4, 1981. They had settled on a $120,000 two-bedroom, two-bath board-and-batten house with a brick facade, fourteen-foot vaulted ceilings, a fireplace, high clerestory windows in the bedroom, bathroom, and living room, tiny landscaped hills in the front yard that looked like the bubbles in a cheese-and-broccoli omelet, and a fenced back yard that separated the house from hundreds of acres of grassland. The front yard would be maintained by the Bent Trail Homeowners’ Association, and Loren planned to landscape the back yard himself, putting in a Jacuzzi and a redwood deck. Theirs is the least expensive home in Bent Trail, where customs alongside the so-called creek that trickles through the middle of the development can run upwards of $300,000.

The Sutherlands spent their first night on the couch, since they had been too tired to fill the water bed. There were no curtains; moonlight streamed in and lit up the house. They had trouble sleeping, but it wasn’t the moonlight that kept them awake—it was the silence. Back in California, they had lived on a hilltop in Marin County, above hundreds of thousands of people and lights and cars. Their new, unpopulated development was desolate. They lay still and listened. They heard no cars idling, no dogs barking, no sirens wailing.

The Sutherlands were the second home buyers to spend a night at Bent Trail. The first, a financial analyst for Arco named Roger Lambert, was already living next door. The suburban settlers stuck together when they were left alone on the 290 acres each night, playing poker, eating roast turkey, and enduring the ominous silence and darkness of a land that’s not quite ready to be lived on. In the mornings, Roger would drive away to the Arco offices, Loren would head for his job as regional sales manager for KTI Chemicals in Carrollton, and Susan would begin her day’s work at GTE/Sylvania as an executive secretary. In San Francisco, Loren had worked as a management consultant—a “headhunter”—for the semiconductor industry, and Susan had been secretary to the president of Gallo Salami. They had been married almost a year when Loren decided to make the move to KTI Chemicals.

After they made the inevitable adjustments to the blue laws and North Dallas’s erratic dry-wet boundaries, Loren and Susan began throwing themselves into the Texas way of life. Loren bought boots. They learned country-and-western dancing. Their friends in California began hearing “y’alls” over the phone lines from Dallas. But their biggest adjustment by far was to life on the edge of a prairie, made all the more desolate for Susan when Loren and Roger were away on business at the same time and she had Bent Trail to herself at night. It suddenly seemed darker, and quieter. And scarier.

“One night Loren called from one of his first trips to Denver. Just after I hung up the phone, it rang again, so I picked it up and said, ‘Hi, honey, what did you forget?’ Well, it wasn’t honey. There was just this man breathing into the phone. That same night, about four a.m., the phone rang again. This time a man’s voice said, ‘I know you’re alone.’ I said oooh-kay, and sat up on the couch the rest of the night.”

Weirdos on the phone lines weren’t the only frightening aspect of life at Bent Trail. The Sutherlands came into contact with strange native fauna. “One night we were sitting around and I heard a sound against the wall, coming from the outside,” says Loren. “Like a pounding sound. I went out to look, and something flashed by me out of the bushes. It might have even been a coyote—I’ve seen a wolf up close before, and it didn’t look unlike one of those.” Roger reported seeing packs of wild dogs roaming around at night.

Susan tells her own story. “I walked into the bedroom one night with a glass and something else in my hands, without turning the light on. I walked back to the living room to get a book and went back to the bedroom. When I turned on the light I saw, right next to my bare footprints on the carpet, this large scorpion. Being from Arizona, I’m used to them, but I’m not used to their being indoors. So I yelled. Loren came in and shoved it in a glass jar. We kept finding them and putting them in the jar, letting them go at it. One week we had six scorpions in that jar. I think they may have lived in the bottom of the planter in the bathroom.”

One afternoon last August, toward the end of one of Dallas’s record-breaking heat waves, Susan noticed a smudge on the clerestory window near the bedroom ceiling. It was on the outside. A few days later, Loren noticed another one right next to it. At two-thirty the next morning, they woke up to a loud thud and discovered what was making the smudges: birds. Blackbirds, sparrows, even hawks, come arrowing across the field north of the Sutherlands’ house, and as they approach it they sometimes try to fly through the clerestory window in the bedroom and out the clerestory window in the bathroom at the front of the house, because they can see the stars out the other side. When the Sutherlands were awakened by a big blackbird slamming into their bedroom window, they went outside to look for it. It was stumbling around, dazed, on the patio. After a few seconds it shook its wings out, took a few steps forward, and flew off toward the south again. Bird-smudge cleaning became another housekeeping ritual peculiar to life on the edge of Dallas.

For a few months Bent Trail was a place where everybody knew everybody else. By early September there was Craig Farkas at the other end of Smoke Glass Trail—he owns a Mama’s Pizza franchise—and there were Harold and Teresa Wilson across the street from the Sutherlands, Judith and Ruth in two houses near the middle of the block, the young oriental couple up near the models; it was a tiny community of middle-class, white-collar workers. For the first six months the post office would deliver mail only to the sales office; whichever homeowner got there first would get everybody else’s mail and distribute it.

“It’s so far away from everything, you’re not constrained,” Susan said a few months after moving in. “You can just walk up to people who are driving by and say, ‘So who are you?’ A couple of months ago a couple were driving by looking at a home they’d just bought, and one of the other neighbors and I flagged them down. We had them in for wine, somebody went out and got a chicken basket, and we made an evening of it.”

Bent Trail got calmer and more populous in the fall. More houses on Smoke Glass Trail were finished, and more people were moving in—there would be thirty couples and families in Bent Trail by the end of December. The Dallas Times Herald finally found a carrier to throw papers on the Sutherlands’ yard. There were bicycles on the sidewalks and babies on the lawns. In order to save Bent Trail’s handful of students a 7 a.m. to 5 p.m. school bus commute to Plano schools, Jerry Stiles bought a $30,000 customized nineteen-seat van with champagne-colored crushed-velvet seats, tinted windows, and the words “Bent Trail Limousine” painted on its sides. Bob West, a project manager for the Stiles Land Development Corporation, was given the job of chauffeuring the kids back and forth to their schools in Plano. Stiles figured craftily that the $30,000 investment might land Bent Trail a nice feature story on the front page of the Times Herald Metro section. He was right.

By wintertime Bent Trail was almost a regular neighborhood, with families spread all through the tract. And the peculiar sort of guardedness that characterizes most neighborhoods began to take over. Suddenly there were cars coming and going all the time where once the Sutherlands might have seen only the construction workers’ pickups all day long. It began to be difficult to tell the visitors from the residents. There were strangers living a few doors away; the strangers didn’t talk to the Sutherlands and the Sutherlands didn’t talk to them. Civilization was coming to Bent Trail.

Loren and Susan threw a Christmas party at their house on a Friday night in December and invited their friends from KTI and GTE, and Harold and Teresa from across the street, to come for snacks and spiked eggnog. The party guests oohed and ahhed as they toured the house, giving the most enthusiastic praise to the bathroom, a lavish, spectacular room with brassy fixtures, two counters and sinks, mirror-covered walls, a step-down tiled bath, and a freestanding, see-through glass shower. In the corner just beyond the bath was a lighted, built-in planter filled with ivy and palms. People were talking about how J. Stiles was famous for his bathrooms. As the party progressed and the eggnog disappeared, a crowd gathered in the kitchen, leaning against the wide counters and taking orders from Susan, who likes to put her guests to work chopping and shaking and stirring and blending.

During the party, the Sutherlands got on very well with the Wilsons. They had a lot in common. They were both young, upwardly mobile couples. Harold was a stockbroker and Teresa, like Susan, was an executive secretary. They all liked to work out at health clubs or racquetball courts or swimming pools, and their houses had the same floor plan.

One of the first things they talked about was the gunshots. Early in the summer Loren had been jogging around Bent Trail with Roger, a marathoner, when they noticed a couple of kids shooting off pistols in the trees a hundred yards to the west of the Sutherlands’ house. It began happening more and more; people were driving down from Preston on a dirt road by the railroad tracks to burn up some ammo. One day in September Loren heard ricochets from what sounded like high-powered rifle fire—he recognized the sound from his Army Reserve duty. He walked out to the side of his house and saw, a couple of hundred yards away, a group of teenage boys carrying pellet guns and a rifle, maybe a .30-30 or a .30-06. They were shooting at something on the ground, and Loren worried that a stray bullet might hit one of the houses.

He walked back inside and called the Dallas police for the first time since moving to Texas. After he hung up, he found himself wondering just how safe it was to be living that far out in the boondocks. Where was the nearest police station? Had the police ever even heard of Bent Trail? In less than five minutes, he got his answer with the appearance of two Dallas police cars. The cops told him that it was illegal to discharge a firearm within the city limits and that he should not hesitate to call when it happened. The next day, he walked out into the field and found scattered on the ground spent shells from 10-gauge and 12-gauge shotguns and from .32-caliber and .38-caliber pistols, and some .30-30 rifle shells. Off near a pile of punctured aluminum cans and plastic milk cartons was the shattered body of a bird.

Loren’s job requires him to travel frequently, and both he and Harold are concerned about their wives’ being home alone. The Sutherlands considered installing an alarm system (all of the Bent Trail models are protected by alarm systems), and during the past few weeks the couples have been looking for guns that the women could use; Harold owns a .357 and a .30-06. They had all talked about it, and they knew several women living in far North Dallas developments who kept handguns in the nightstands near their beds and knew how to use them. Susan has had some experience with guns, since she used to shoot with her father when she was a girl. She’s planning to get a lightweight Colt .38 to match the one Teresa will buy, and the two women will learn how to use the pistols at a regulation gun range not far from Bent Trail.

A lazy gray cat named Shitzu lumbered across the Sutherlands’ living room floor to where Loren sat drinking from a glass of iced Chablis. It was a warm Saturday afternoon in the dead of winter, and it was quiet outside—no gunshots.

“The one thing bad about Texas,” Loren said, “is it’s flat. We miss California for that sometimes, and the sunsets, well, here . . .” He walked over to the fourteen-foot-high fireplace and took some photographs down from the mantel. “This was the view from our back door.” In the glossy color photograph were rugged, tree-covered, dark green hills; the sky above them was ablaze with a fiery Pacific sunset.

The view from the Sutherlands’ new back door is less spectacular. A sliding glass door opens onto a cement patio, beyond which is a small yard covered with crusty gray earth, bits of gravel, and weeds. To the west, a more austere sunset was forming in the big Texas sky, and to the north, about two hundred yards away, train tracks glistened with reflected orange light. Beyond the tracks, through a thin line of trees, you could make out the framing of two houses under construction in Plano.

Loren kicked at some gravel in the yard and pointed out where he planned to put in Japanese fir trees, lay down pebbles and stones as a little creek bed for the rivulet that appears when it rains, and install the hot tub and redwood deck. Once the back yard is finished, he and Susan will buy a golden retriever. A few years from now, the couple may buy a custom home in Bent Trail, using Loren’s knowledge of architecture to design a house that would be half kitchen, since they both have a passion for cooking and entertaining. They don’t have any immediate plans for having children, preferring instead to lavish gifts on Loren’s two-year-old daughter, Amy, who lives in El Paso with his ex-wife. Somewhere down the line Loren may decide to enter Texas politics, possibly as a candidate for state senator.

Jerry Stiles considered going into politics himself last year, maybe to take a stab at Jim Collins’s Third Congressional District seat. (“I have as high an amount of name identification as anybody,” he quipped. “I’ve got more billboards than goddam Coca-Cola and General Motors in that district!”) In the end, he decided he couldn’t give up the competitive, fast-paced, changing-every-minute North Dallas real estate business. It’s like a narcotic to him.

“I grew up in this business,” he says, leaning back in his office chair and wearing his usual attire: faded jeans, boots, a Western shirt, and a hand-tooled leather belt with “J.D.S.” stamped on it. “My dad was a production superintendent for a large tract builder by the name of Northwood Homes. I worked on Daddy’s jobs from the time I was in the seventh grade, back in 1957. That was twenty-five years ago, when they were basically building along Central and Royal Lane. That was the boondocks then, because it was the farthest north Dallas came. There was no such thing as NorthPark, and the only multistory building on Central Expressway out of downtown Dallas was the Meadows Building. And in just twenty-five years you can’t even see the sky along Central Expressway on either side from downtown Plano on in. There wasn’t anything out Preston Road, and once it got past Inwood, Royal Lane was just a gravel road.

“The sixties pretty much filled in from Forest to LBJ, and in 1968 I built my first house, just on the other side of LBJ at Hillcrest. Back then, nobody would cross LBJ, and now people are saying, well, Plano’s all right, that’s not so far out. That’s ten miles north of there! Royal Lane, it’s in the heart of downtown Dallas.”

Stiles has built more than 1500 homes since his first in 1968, everywhere from Denton to Rockwall and Houston. He’s successful, he says, because he knows his market. “At Bent Trail we decided that young professional people would be the buyers, that more than likely they would not have children, or if they did, they’d be under school age. So this tells you that you have to cater to that person’s lifestyle. They don’t want traditional things like Early American, fleur-de-lis wallpaper, eight-foot ceilings —they’re not going to buy that, because that’s what Grandmother had when they were growing up.

“Today people stay in apartments the first ten years of their adult life, and they want that lifestyle. We give them a swimming pool, give them vaulted ceilings, fireplaces, and they don’t have to take care of anything, just call your manager and we’ll come fix your hot water heater and your front door if it doesn’t lock, and if you have a leak we’ll take care of that, and obviously nobody’s going to have to mow the yard. Apartments have had as much effect on our design criteria as anything in the business, if not more. That’s the reason we have the association, so there’s no maintenance of the front lawn —it’s fully sprinklered and landscaped when they move in. The only thing they have to do when they move in is to drape the windows, and we’ll even do that for them if they pay us. They can move in and be living tomorrow night as if they’d been there forever. That’s what the buyer likes.

“They also want pizzazz, and they want high style, and they want sex. My parents and your parents grew up when sex was something that was not talked about. Sex is an okay thing to us—it’s not a dirty thing that we have to be ashamed of. That’s why people like our houses, the reason people are comfortable in them, because it’s nothing but a sexual environment. Nobody in the world would have bought clear glass showers ten years ago. What, stand there and let my husband see me take a shower? Ten years ago, nobody would ever have bought a house that had a big picture window right over the bathtub, and a clear one at that. If it wasn’t obscured glass, forget it. Somebody would crawl over the fence and look in! Today, they won’t buy it without it.”

For the time being, though, it seems that high mortgage rates and the difficulty of getting bank loans are keeping the apartment generation in its apartments. One hundred and seventeen houses were started at Bent Trail in 1981; by the end of the year, 82 had been completed, and only 30 of those had been sold.

“Very candidly,” says Stiles, “that’s not a good performance. There should have been at least a hundred people living in Bent Trail in its first year, under normal circumstances. It’s just pretty damn typical of the entire marketplace. The attitude of builders in late November and December and even the first couple of weeks in January had been so optimistic. There had been some sales and there had been some slackening of the interest rate, and the lenders were beginning to say, ‘Well, maybe it’s over.’ But for the last three weeks, when Reagan started hinting about a ninety-one- or ninety-seven billion-dollar deficit, it was as if he just threw a bucket of water in the building industry’s face, and everyone’s saying, no way, we’re not going to do one goddam thing more till we find out what’s gonna happen to us. If anything, it has gone to a worse condition right now than it was in all of 1981. I think 1982 will ultimately be a slight improvement over 1981, but it’s not gonna be what we had hoped for in November and December.

“I’m concerned that because S&Ls have been so drastically hurt with this recession and inflation they have lost their desire to be in the house-lending business. Who’s going to replace them? Everyone’s saying, well, maybe they’ll come from pension funds and investment groups, but it won’t happen rapidly. I’m concerned about whether or not we will have adequate money in the system for the cost of mortgages ever to be reasonably acceptable again. But something will work out, hell.” Stiles flashes a grin. “I’m just not smart enough to know what it’s gonna be.”

Bent Trail represents an ending to a century of growth in North Dallas. After Bent Trail is built up, there will never be another house built northward in Dallas. Like many Dallas developers and real estate people, Stiles thinks that the homebuilding industry has nearly seen the end of front and back yards, of 75-by-120-foot lots, of grass and trees and backyard swing sets. It’s quite possible that the growth northward into the undeveloped land in Plano will be an unbroken flow of apartments, townhouses, and mid-rise and high-rise condominiums.

And what of Bent Trail? Well, that’s something about which Jerry Stiles is eternally optimistic. He has no trouble closing his eyes and seeing it as a community of 1224 families, with townhouses to the north of Smoke Glass Trail, townhouses and apartments on the south half of the Lloyd tract, single-family homes on the north half, and maybe 1-acre lots on the 25 acres of pecan-tree-shaded land to the west of the Sutherlands. There’s talk that the floodplain adjacent to the western border of Bent Trail may be taken over by the Dallas Parks Department and converted into parkland, with 8 acres in the southwest corner of Bent Trail taken by eminent domain as the site of a future recreation center. A strip of land running alongside the railroad tracks in the north won’t be touched; it’s reserved as the right-of-way for U.S. Highway 190, which may one day loop around Dallas much as LBJ does today. Who knows? Maybe fifteen years from now Highway 190 will be the new border between old, established Dallas and the new frontier, and the Sutherlands will look around them at the traffic and the malls and the Burger Kings and the hot-rodding teenagers and think about moving northward to a house where they can sleep in moonlight and silence, in a land where wild dogs and scorpions come out at night.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Plano

- Dallas