High above the floor of Kemper Arena, cool and crisp in a three-piece suit, John Tower rested his binoculars on the table and assumed a thoughtful pose. Thirty yards below, swigging watery soft drinks amid the tumult and steam of the Republican Convention, sweltered the Texas delegates, one hundred strong for Ronald Reagan. John Tower could see them; but they, unless they craned their necks and peered over the railing up to the glass facade of Sky Suite H, could not see him. That was for the best, since they considered him a villain, unwelcome at their caucuses. An “Officer of the Convention” badge hung, face downward, around his neck, alike in every respect save one to the “Delegate” badge he could have worn if Gerald Ford had won the Texas primary.

Ensconced in that low-ceilinged presidential command post, accompanied by a half-dozen other White House confidants, Tower was tired but happy. He had spent most of the previous night helping the President choose a running mate, and his argument—that Robert Dole was the man to boost the ticket in the South—had finally prevailed. Now he was awaiting Dole’s formal nomination and the arrival of dignitaries due to pay their respects at Sky Suite H. He listened testily as a visitor described how the Texas delegates, mindful that his Senate term will expire in two more years, had enlivened their caucuses with cheers for his potential Republican opponents. “I’d rather have them take their fury out on me than on the President,” he answered solemnly, gazing out across the crowd as if to draw strength from the massed blue Ford/Dole placards. His reverie lasted only a moment; abruptly, he waved his hand across the table and told a passing aide, “Get these glasses cleaned off. We’ve got the Cabinet coming here.”

Tower was in Sky Suite H minding the store because he had sided early and forcefully with Gerald Ford in the Texas primary. The Ford slate was top-heavy with Tower’s friends and party allies; the more he stumped the state for them, the more he put his personal prestige on the line. Reagan’s sweeping victory cost Tower far more than his delegate’s credentials and his chance to be Ford’s floor leader in Kansas City; it left the only statewide officeholder Texas Republicans have had in this century alienated from a large segment of his state party with his own reelection campaign less than two years away. The first sign of Tower’s weakened position back home came in September, when he surrendered the chairmanship of Ford’s presidential campaign in Texas to his old enemy, John Connally. Prudence left him no other choice, a fact he obliquely noted with self-deprecating humor while introducing to reporters the man who had been his political adversary for much of his first decade in public life. At the Republican State Convention two weeks later, State Party Chairman Ray Hutchison survived a challenge from Ray Barnhart, leader of the Reagan delegates, only with Connally’s energetic help; earlier in the summer the national committeeman and committeewoman, both Tower loyalists, had been replaced. Tower himself ventured just briefly before the September convention; though, as the votes were being counted in the race for chairman, he stood concealed behind the auditorium curtain checking and rechecking his personal tally sheet.

Nineteen seventy-six has been a less-than-joyous year for Tower on the national level, too. His party made no headway against the Democrats’ 62-38 majority in the Senate, meaning that he will again be faced, as he has each year since his arrival, with the frustrating disadvantages of minority status. Ford’s loss to Carter took away Tower’s influence over federal patronage in Texas, terminated whatever cordial personal ties he had been able to establish with the top echelons of Washington bureaucracy, and vastly diminished his White House access. It also squelched any chance he might have had to defeat Michigan’s Robert Griffin in this month’s race for Senate minority leader, since Griffin’s biggest disadvantage—the underground Senate feeling that two Michiganders in such high places would be one too many—is now inapplicable.

In addition, Tower and his wife mutually agreed to file for divorce. Though the proceedings were amicable and uncontested—former Republican gubernatorial candidate Paul Eggers handled both sides—his 25-year marriage is now at an end.

Back in 1961, when he was 35, things must have seemed so much greener. On the night of May 27 that year, spontaneous caravans of celebrants had snaked their way down Houston’s South Main street, honking, waving posters, and cheering into the small hours of the morning. John Tower, an obscure professor of political science at a hardly less obscure North Texas college, had outlasted seventy other candidates to win, in a runoff, the United States Senate seat held of late by Lyndon Johnson. It was the political upset of the century: Tower was a Republican, the first such breed in the Senate from Texas since Morgan C. Hamilton, an uncompromising scalawag, had retired in 1877. His election was widely thought to augur two things: the advent of a genuine two-party system in Texas, pleasing to both Republicans and liberal Democrats alike, and the arrival on the national scene of an outspoken, articulate conservative hero.

It in fact did neither; and thereby hangs the tale of John Tower. What it did do was launch him, with his decidedly human faults and virtues, into a Senate career that has already lasted the better part of two decades. And nobody, least of all John Tower, expected that.

John Goodwin Tower likes to remind audiences that he was born a blue-and-gray Southern Democrat. His childhood was spent in the cities, small towns, and fields of East Texas during the Depression decade of the thirties, an era when twilight began to shroud the memory of the Confederacy. The central, ancestral fact of Tower’s life, however, is religion—his father, Joe Z. Tower, was a Methodist minister, as were both his grandfathers and his great grandfather on the Goodwin side. The Senator himself is said to be capable of delivering a spellbinding sermon on occasion. From his father he inherited an impressive collection of Texana and archeological artifacts, but little in the way of cash. A preacher’s income is ordinarily low but dependable: God, a youngster learns after Sunday collection, does somehow provide; but seldom extravagantly. Young John spent summers working at the soda fountain of his uncle’s drugstore in San Augustine and nurturing an interest in such mundane subjects as politics and history. “He was very precocious and curious about everything,” recalls his paternal aunt, Ten Tower, who lives in Dallas. (She got her name, logically enough, by being the last of ten children.)

Tower’s adolescence was cut short by World War II. Not yet twenty when Japan surrendered, he had already spent three years in the Navy and served on a gunboat in the Pacific. He came back from the war “rather quiet,” says Aunt Ten. “He didn’t talk much.” Soon he enrolled at Southwestern University in Georgetown, working part-time as a disc jockey and newscaster on radio station KTAE in nearby Taylor, using the airwave handle “Tex” Tower. His BA in political science, earned in 1948, and further work at SMU supplied credentials for a term of graduate study at the London School of Economics in 1952. Next to his impecunious childhood, the war, and his election to the Senate, that year did more than anything else to shape the future John Tower. He returned to Texas a confirmed anglophile, attentive to every nuance of British gentlemanly style. Married to Lou Bullington, the daughter of a prominent Wichita Falls family, Tower served on the faculty at that city’s Midwestern University for most of the fifties. He involved himself in civic affairs and took an active interest in the local Republican party, which he had joined in 1951.

In 1960 the Republican party of Texas was as negligible as Republican parties elsewhere in the South, amounting to little more than a conduit by which the national party distributed federal patronage whenever the GOP was fortunate enough to control the White House. To keep up appearances it continued to run statewide candidates, none of whom could reliably expect to receive as much as 20 per cent of the vote. Tower, a four-year veteran of the State Republican Executive Committee, volunteered for the kamikaze task of opposing Lyndon Johnson’s bid for re-election to the Senate. Johnson had bald-facedly contrived to change the Texas election laws to provide himself a safe return to his current job in case the voters rejected the Kennedy-Johnson national ticket. The chance to run against him was not regarded as a thrilling prospect. But Tower—so little known that the party’s rising political operative, Peter O’Donnell, met him for the first time at the convention where he was nominated—wanted the job, so he got it. He lost, but he took 40 per cent of the vote; and when Johnson went off to the vice-presidency, leaving behind creaky old Braniff executive Bill Blakley as the interim senator, who among the Republican leadership could deny the feisty little professor the chance to run again?

Tower’s peculiar 1961 victory in a nonpartisan special election did much to set the tone of his early Senate career. Fort Worth Congressman Jim Wright, a middle-of-the-road Democrat, had been the favorite to succeed Johnson; but Texas labor leaders were disenchanted with him and actively supported liberal San Antonio attorney Maury Maverick, Jr. That split let the archconservative Blakley slip past Wright into the runoff by just 19,490 votes. Wright could easily have bested Tower; but Blakley was another matter. The 62-year-old establishmentarian was anathema to liberals, and in those days, the dominant school of Texas liberal theoreticians held that their side should systematically oppose conservative Democratic nominees, even if that meant electing Republicans, in order to drive disillusioned conservatives out of the Democratic primaries and leave liberals in control. The strategy was called “Democratic rebuilding.” In pursuit of this chimera, editor Willie Morris of the Texas Observer made “an appeal to reason” urging a “conscious liberal vote for Tower.” Further aided by a small turnout, Tower edged Blakley with 50.6 per cent of the vote, getting only 448,217 votes, less than half as many as he had gotten in his 1960 loss to Johnson.

Tower was expected to teach conservative Democrats a lesson and disappear, an amusing footnote to history, in the 1966 election. Instead he drew another conservative Democratic opponent, State Attorney General Waggoner Carr, causing the liberals to make another stab at rebuilding—and helping send Tower back to the Senate for six more years. In 1972, having raised an impressive campaign war chest, he rode the crest of the Nixon wave; but his third victory was at last convincingly personal: he got more votes than any previous statewide candidate in Texas history and set to rest the charge that his presence in the Senate was a fluke.

Still, none of it could have happened except for 1961. After three terms and fifteen years, John Tower is a monument to the miscalculations of his political opponents: a legacy of LBJ’s vast ambition, of labor’s shortsightedness, and of a liberal Democratic strategy too clever by half.

He ambulates through the Capitol corridors like a little motorized man, aides trailing respectfully in his wake.

Ralph Yarborough, the gregarious liberal Democrat who comprised the other half of Texas’ Senate delegation in the sixties, was legendary for taking meals in the Senate’s public cafeteria, where celebrity-spotting constituents could interrupt him until his food grew cold, precisely as he’d hoped they would. Tower, by contrast, prefers to lunch with an aide or two in the dark privacy of a Capitol Hill restaurant called the Monocle. He is a far cry from the stereotypical glad-handing politician. At any gathering he projects an attitude of aloofness and detachment. On occasions when most politicians would relish the chance to mingle with the crowds, Tower as likely as not can be found sequestered in his hotel room, chatting with a few friends, far from the popular activity. Small talk obviously discomforts him; he rarely takes pains to be outgoing, even when doing so would be politically expedient. When accosted in the hallway by an inconsequential admirer, he has an unerring, and dismaying, ability to discharge rote pleasantries while leaving the impression that he has been offended by the conversation in some strange, not-to-be-disclosed way.

He ambulates through the Capitol corridors like a little motorized man, aides trailing respectfully in his wake. Hill staffers regard him as one of the least approachable senators. His aloofness is a kind of invisible carapace thrown up to protect his privacy—the response, friends say, of a painfully shy person who is not to the political manner born. Beneath it one occasionally catches glimpses of a genuine warmth.

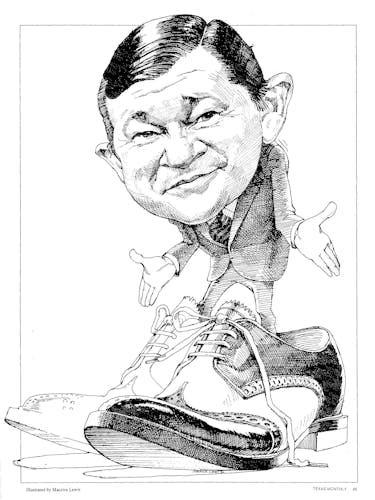

But shyness is probably not the whole story. Tower is phenomenally short—five feet six, he claims, which seems generous—and there must be something unsettling about mingling with a crowd when you are so short that everyone is looking at the top of your head. He is noticeably more at ease sitting down than standing up. On the whole, Tower has borne the discriminations of a heightist society with cheerful fortitude. “My name,” he has explained to audiences for years, “is Tower. But I don’t.” When a reporter suggested that he gave speeches from atop soft drink crates behind lecterns in order to conceal his true height, he responded that, au contraire, the crates provided “the sole means by which the audience could perceive me at all.” Tower could readily be described as elfin, were it not for the fact that elves do not wear three-piece pinstripe suits and carry gold cigarette cases. He has elected to cut a dignified figure. He makes regular trips to London—at his own expense, he points out—and stays at the Savoy Hotel on the Strand while the clothiers of Savile Row fashion his hand-tailored suits.

The dignified look, though impressive, has not been an unqualified success. Any way you cut it, he is still short. Columnist David Broder once described him as “a tiny dandy who dangles his toes from his swivel chair and favors English cigarettes.” People are still chuckling over the encounter, several years back, between Tower and Austin Congressman Jake Pickle. According to the story—which for once is not apocryphal but entirely true—Tower was pointing out the fine touches on his latest suit and telling Pickle how extraordinarily low the prices for such workmanship were. Pickle, a rather bulky man, took it all in before inquiring, deadpan: “And what would it cost in a man’s size?” Tower, floored, is said to have walked away muttering something about Pickle needing a “tent size.”

The point of all this is that Tower, as a result of what he calls “an immutable condition ordained by the Creator,” lacks the natural politician’s most coveted asset: physical presence. Savile Row cannot fully make up the difference. He has a way of fading into the woodwork whenever he relinquishes a spotlight. At the press conference where Tower gave up the chairmanship of Ford’s Texas campaign, John Connally took center stage and fielded all the questions while Tower stood nearby, his unbuttoned coat pulled back by his hand resting on his hip, chain-smoking and listening; no one asked him anything. And when, after twenty minutes, he tried as host to end the proceedings, the press ignored him, continuing to ask questions until Connally himself drew matters to a close. The same thing happened at his “joint press conference” with Robert Dole in Austin.

The only time one can be certain it will not happen is when Tower is making a speech or engaging in repartee. As an orator he is nothing short of brilliant; it is his greatest strength. Especially in extemporaneous debate, on or off the Senate floor, he is a magnetic public speaker—alternately witty, eloquent, folksy, elegant, and forceful. He speaks in paragraphs: you can hear the colons, the semicolons. He never rants, has a striking command of factual detail, and builds his chosen mood with a sure sense of timing. The ability is downright uncanny. “You may not agree with him,” says a Texas Republican who often doesn’t, “but when he’s finished you have the nagging feeling that if you were intellectually honest with yourself, you ought to agree with him. He makes Goldwater look like a fence post.” At a pre-election debate with Senator Ernest Hollings before a convention of General Electric managers, the South Carolina Democrat answered an awkward question about his views on Walter Mondale with a great deal of rhetorical heat and very little factual light. Tower stepped to the podium, surveyed the audience, and said softly, “I regret [pause] that I lack [pause] Fritz Hollings’ oratorical abilities in the tradition of Pitchfork Ben Tillman [pause], and his height [pause], and his good looks [pause], however . . .” and then BLAM!—a point by point appeal to logic and emotion, building to a crescendo that left the conventioneers cheering.

One other thing about Tower must be mentioned—his reputation as an aficionado of wine, women, and song. (Some would omit the “song.”) Tower is not what is to be called a “high liver,” and except for his clothes he is not an extravagant man. But he does like to surround himself conspicuously with beautiful women, whose company he enjoys. His extracurricular reputation as a lothario has become so welded to his public image among friend and foe alike that some have wondered out loud why he has let it happen. But the fact is, he seems to view it less as a burden than as something to flaunt; it is not an image he tries very hard to erase. “My best friends tend to be women. That’s supposed to be characteristic of us Libras.”

Writers are inevitably drawn to mouth clichés about how “complex” a given public figure is, but Tower is actually one of the less complex people around. There is very little about him that is enigmatic. The wellsprings of his character lie near the surface. If there is one thing the electorate consistently fails to grasp, it is the degree to which public figures consciously construct personal images which, even if not ultimately flattering, admirably serve the purpose of distinguishing them from everyone else. Tower’s playboy image is merely one example. In addition, he is a man who never lets his very real qualities of personal compassion and generosity get in the way of his image as a distant, supercilious, penny-pinching trustee of the public weal. For many years he has quietly sent substantial sums of money to support individual orphans overseas, but you would never know it from anything he says. The image he projects is quite different from the tough-guy stance of someone like Jack Brooks, but it is equally designed to conceal the traces of softness or sentimentality. It rarely cracks. One time it did was at the meeting of the GE managers, when Tower was called upon to defend the concept of the all-volunteer Army. He admitted that the new approach caused problems in military training; but it had, he said, one aspect that made it vastly preferable to the draft: “There are no more young men serving in our armed forces . . . in anguish.” His voice drew across the word anguish like a bow across a cello, resonating with unexpected sympathy toward those whose judgment of the last war had been so different from his own.

Why—given his innate, intelligent, well-spoken conservatism, has Tower not laid claim to a role of preeminent leadership within the American conservative movement? In his first term he seemed headed—erratically, to be sure—in that direction; and a decade ago it could well have been his for the asking. Instead his career took an altogether different turn.

Aware, he says, that he was “something of a political freak” because of his bizarre 1961 election, Tower arrived in Washington determined to enjoy to the hilt what he fully expected would be his one and only term. He relished his newfound celebrity status, traipsed around the country giving speeches at the expense of Senate attendance, freely lent his name to conservative organizations’ letterheads, despised the nitty-gritty of committee work, and sponsored what one aide called “the Tower approach to this and that” in a legislative package that went nowhere. His indifference to serious Senate business drove his staff to despair, and he repeatedly made mistakes of judgment that a more seasoned politician would have avoided. He acquired the playboy reputation that has followed him ever since. Many of his colleagues privately dismissed him as a clown.

That phase lasted until 1968, when the reality of his surprise reelection finally sank in. He decided that championing right-wing causes was a dead end, at least for the kind of Senate life he would prefer if he was actually going to be a senator instead of just play at being one. The reasons for that decision will be discussed in a moment; but the effect was to close the door permanently on his becoming a national conservative leader. In the Senate he began the long process of reclaiming respectability as a member of the club. And once a Republican administration took office in 1969, he put his main efforts into trying to get his point of view engrafted into legislative programs during their formative stages within the executive agencies. To his annoyance, that approach was not particularly effective either. By 1971, he had begun the shift to his third—and current—strategy: maneuvering unobtrusively behind the scenes in the Senate, seeking results through low-profile legislative tinkering.

That strategy has worked. Given the rather limited goals Tower has set for himself, he has finally begun to hit his stride. He is not one of the Senate’s heroic figures, but neither is he the insignificant lightweight that many Texans still suppose him to be. The transition is worth remarking, because once a politician has spent a few years in Washington, he is usually stuck with whatever reputation he has earned. Tower managed to change his.

Like most other senators who are not running for president, Tower’s impact on the legislative process is governed in the first instance by his committee assignments. Fifteen years of seniority have pushed him near the top (he will rank sixth among all Republicans in the new Senate). As the number two Republican on Armed Services, he pursues a consistently hardline defense policy sympathetic to the Pentagon. His most acrimonious moments in debate this year came as he supported the B-1 bomber and the A7 fighter against the opposition of two liberal Democrats. Though South Carolina’s Strom Thurmond technically outranks him there, Republican doubts over Thurmond’s persuasiveness have led Tower to handle most of the floor-managing duties that normally fall to the senior man. On the Banking and Housing Committee, Tower is the ranking Republican member. His cordial relationship with its Democratic chairman evaporated when Wisconsin’s William Proxmire took over the committee from Alabama’s John Sparkman in 1975. Tower now plays a distinctly adversary role, trying (with noticeable success) to win over a Democrat or two to block or alter Proxmire’s proposals, and leading the floor opposition if he fails. Except for having to put up with Proxmire, Tower now seems actively to enjoy his committee duties—the very thing he scorned fifteen years ago. He cites his work on the Financial Institutions Subcommittee as his personal favorite. But on the whole the business at Armed Services—mainly authorization, pro or con, of Pentagon proposals—offers a more salubrious climate for him than the business at Banking, where extensive legislation constitutes most of the agenda. He is more comfortable as a responder than as an initiator.

Searching for a phrase to sum up Tower, a Texas lobbyist finally exclaimed, “He’s not an offensive running back: he’s a linebacker who tries to cause fumbles.” Few Republicans, especially conservatives, have been in a position lately to embark on major legislative initiatives. Playing defense has perforce been their game. Tower routinely carries a variety of things vital to the constituents back home, of course, but all senators do that. He gives special attention to matters involving energy, labor, and agriculture. Otherwise, he usually is content to revise and resist whatever Democratic programs he deems extravagant or misguided. “When we need his help,” says one lobbyist, “it’s most often when we want something not to happen.” At the end of the last session, Tower was instrumental in blocking liberal efforts to impede the Arab boycott, and he helped prevent the adoption of amendments to the Clean Air Act ardently sought by environmentalists. Elwin Skiles, a Dallas lawyer who recently retired as his administrative assistant, puts it this way: “Legislation is not always an affirmative act. Just because something doesn’t have Tower’s name on it doesn’t mean he wasn’t right in the middle of it.”

Certain personal qualities characterize Tower’s performance. He is a gifted strategist with a keen understanding of the various psychologies of his individual colleagues, especially the Southern Democratic mind; it lets him call the shots on an upcoming vote expertly. He is an even better tactician, whose above-average knowledge of the rules is put to best advantage on close votes, veto overrides, and cloture motions. He is candid, with a reputation among his colleagues and among lobbyists of sticking by his promises. Despite the fact that his attendance record hit 91 per cent this year, he is on no one’s list of the hardest-working senators—busy, yes; but hard working, not really. Some even call him lazy. Good friends refer delicately to their need to “work within his energy range,” and a leading lobbyist observes: “On an issue John takes an interest in—gets intrigued by—he can be a bulldog; but it’s sometimes difficult to, uh, get his attention.” And that streak of aloofness in his personality is sometimes perceived as arrogance on the Hill; there are those professional Tower-watchers who believe it has had “an adverse effect on his colleagues” and may have been the underlying reason he failed to stake out a strong claim to the minority leadership. Nevertheless, he is on basically good terms with the other members, and he is scrupulously careful to maintain what an aide called “a sense of ultimate decorum” in his dealings with them.

Tower does not have as many close, intimate friends within the Senate as might be expected. He attributes this to the fact that he regularly returns to Texas on weekends and isn’t around “to play golf or tennis.” (He does not play either game.) Nor is he “aligned with any clique” in the Senate—including the conservatives’ steering committee and the liberal Republicans’ Wednesday Club. He has a first-rate working relationship with those Texas House members who want it (some don’t). His staff is able—at the top levels, strikingly so—and they have helped smooth the way with House Democrats.

Tower’s recent Senate performance offers an explicit portrait in partisanship. His unabashed belief that the duty of the opposition is to oppose—rooted in the admiration of British parliamentary politics he brought back from London in 1952—has helped make him the quintessential team player. Since 1973 he has chaired the Senate Republican Policy Committee, a position which requires its holder to downplay personal ideology in favor of party loyalty. By all accounts Tower has done an exemplary job. He is inclined, says Oregon’s liberal Bob Packwood, “to lean hard on your sense of two-party conscience: ‘The President is for it, the Republicans are for it, you’re a Republican, so by God go down the line on anything.’ ” Tower is the best jabber the Senate Republicans have; and Packwood, who is himself not noted for hewing tightly to the party line, acknowledges that “there are few people I’d rather have on my side in a partisan cause.”

Nowhere has Tower been more visibly partisan, or more of a team player, than in his relations with the Republican White House. He has displayed a readiness to do virtually anything the last two administrations have wanted done on Capitol Hill, behavior that in the eyes of many has brought him perilously close to being a presidential errand boy. Such devout loyalism has not, on balance, been equitably repaid; Nixon abused him unmercifully (by, among other things, concealing from him until the last minute the news that his old Texas foe, then-Democrat John Connally, was to be named secretary of the treasury) and Ford badly undercut him by signing the 1975 energy bill after leaving Tower with the impression he would veto it. Tower stoically tolerated everything. He did not break with Nixon until after the “smoking gun” tape was disclosed on August 5, 1974. And his cumulative voting record shows him siding with the administration position on 67 per cent of the votes under Nixon, 75 per cent under Ford.

Tower, in sum, is one of the Senate’s most predictable members. There is seldom any aura of suspense about him. Some politicians—Barbara Jordan comes to mind—shrewdly project the impression that their votes could go either way, thereby gaining the leverage that comes from being wooed. He plays no such games, and in fact seems to take pride in being straightforward about his positions. People can argue about whether his voting record represents what’s best for Texas, but for the most part that is a matter of taste; what is clear is that he follows the line of orthodox conservatism. The liberal ADA gives him a cumulative rating of 2.5, the conservative ACA, a cumulative 92. In the session just ended, the League of Conservation Voters ranked him fourth lowest in the entire Senate with a rating of 4, fully 22 points below the average for all Republicans. COPE, the political arm of organized labor, lists him as having voted “wrong” on 117 important labor issues in the past fifteen years. Public Citizen, the Ralph Nader organization which rates each senator on the basis of his “key votes” in consumer protection, tax reform, regulatory reform, ecology, energy, and subsidies, declared that Tower picked the “right” side on 1 vote out of 71—second lowest in the Senate. (Asked about that, Tower responded that siding with Nader “was unconscious, I assure you.”)

As a result of his partisanship, Tower’s influence within Republican circles is substantial, while outside them it is next to nil. The alliance he sustains with several aging Southern Democrats is unlikely to outlast men like John Sparkman and John Stennis. One youngish Southern Democrat, typical of the new breed, remarked that in the past two years, “I’ve probably not spent a total of four minutes off the floor in the presence of John Tower.” Tower considers himself “a relatively influential senator, to the extent that a member of the minority party can be.” But he has come to stand for not much more than following the party line. Anyone inclined to study the fate of the pure partisan in American politics could do worse than examine what has become of John Tower.

Three reasons emerge for Tower’s failure to assume the mantle of American conservative leadership. The first, evidenced by his mature Senate role, is that he wants to be a team player—and that is incompatible with the independence required of an ideological standard-bearer. The second is that he has an ambivalent attitude toward leadership: the trials and tribulations of guiding other people appeal to some men more than others, and Tower has never been comfortable being a Leader with a capital L. He lacks, for one thing, the last full measure of egotism a successful leader usually has; for another, he surely senses that the need for a soft drink crate has lessened his chances from the start. His feelings toward the job are summed up in his slightly disdainful description of it as “The Pope of Conservatism.” Good Methodists have no use for popes.

The third is that there is something else he has always wanted more: acceptance in the larger world of Washington politics. “Acceptability is more important to him than ideology,” says a Republican who has dealt with Tower for years. “There was a time,” says a Tower family friend in Washington, “when Barry Goldwater, Strom Thurmond, and John Tower were considered three of a kind. He felt that was damaging to his image, and he ran from it.” Even in his first term, Tower drew a fine line between right-wing causes he would aid and those he wouldn’t; he had a deep-seated fear of being perceived as a mouthpiece for ultraconservatives, especially the highly unpopular mid-sixties Texas breed. “He never allowed himself to be enveloped by the conservative power structure,” says one top Republican. “Those groups want total ideological agreement, and Tower chose not to be pushed.” Tower himself accounts for the change as “a gradual maturing process.” But others say it was a conscious choice, intended to make him more attractive to the arbiters of taste whose approval he desired.

As long as Tower and everyone else thought his presence in the Senate was a fluke, there was not much incentive for him to rehabilitate his image. “The thing that changed Tower,” says an old friend, “was when he became socially and politically acceptable in Texas after the 1966 election.” Once it became obvious he was destined to be in Washington for at least six more years, influential Texans vied for his favor. He was impressed. At the same time, he was fully aware of the alternative: the right wing had been looking for a rallying point since Goldwater’s 1964 loss, and the 1966 elections had failed to produce any shining new lights except for Reagan, who lacked a national forum and a political track record. The moment of truth came at a luncheon where Tower was offered the chance to do a This-is-what-I-believe, This-is- the-way-we-should-go type article for a major national magazine: in effect, an audition for the job of Conservative Pope. He agonized over the opportunity for several days, wavered, and finally decided to let it pass. Faced with a clear-cut choice, he foreswore any quest for the conservative leadership and began to cultivate the establishment—the Texas corporate and country club elite, the Senate club, and the judges of respectability and taste.

It should be noted that Tower has pursued acceptability as distinguished from status. Many of his critics within and without the Republican party of Texas scorn what they call his pseudo-aristocratic pretensions. But Tower is not an aristocrat, nor is he trying to be one. The attitudes shaped as an East Texas preacher’s son are too ingrained to discard; underneath, he is down-home and always will be. He has polished his establishment veneer to a high sheen, but he still knows who he is. He is content to sit with the people who sit at the head table. Being senator lets him do it.

The celebrants honking their way down South Main that night in 1961 expected a two-party system to arrive in Texas with the dawn. More than fifteen years later, they are still waiting. Conventional wisdom holds John Tower responsible for the delay: he has, say his accusers, held the party in bondage and appropriated for himself the fruits of its labors. Is the accusation fair?

Compared to the sprawling Democratic party, the Texas Republican party is like a family. And its disputes are like a family feud—singularly acrimonious and often bloody. For a generation, the basic reality of the Texas Republicans has been the split between their Houston and Dallas wings. The stereotypes of each, though oversimplified, reflect the way Texas Republicans think about themselves. Midland and West Texas Oil Field Republicans have recently shown an affinity for the Houston outlook; Tyler and East Texas Oil Field Republicans, for the Dallas one. There are exceptions everywhere of course; but on the whole the two stand for distinctly opposite philosophies of what the party should be.

Dallas’ wing tends toward a smooth, modulated, polite conservatism with a touch of elitism and exclusivity; Houston’s, toward a rough-and-tumble ideological passion more suited to a mass rally than a country club. One can picture the Houston Republicans accepting George Wallace’s followers into their fold and trying, perhaps, to purify them; the Dallas Republicans seem a bit too fastidious for that.

The disputes are often couched in terms of “pragmatism” (Dallas) versus “principle” (Houston). State Chairman Ray Hutchison, a personification of the Dallas style, delivered to the last state convention a pounding, one-line summation of his faction’s philosophy: “The purpose of this party is to influence government.” To understand Texas Republicans, one must know that the Houstonians think such talk too often translates into nothing more than scooping up the government’s patronage and largesse; what should be done first, they say, is to take firm ideological stances that “let people know where the party stands,” and then wait for the inevitable stampede of converts. Deep down, the Houstonians think the Dallas wing is run by snobs who want to build a fence around Republicanism: “A party of the living room and the country club is more congenial to some people than one that requires coliseums and sports arenas,” sniffs Houstonian James Lyon. Deep down, the Dallasites think the Houston wing is infested with mad dogs and maniacs who, once in control, would take ideological stances so extreme that (in the words of one Dallas lawyer) “our party would become a laughingstock and we’d never get back in power”—a view which blithely overlooks the fact that pragmatism hasn’t exactly left the Republicans rolling in success. Against the Dallas attitude that the party will “self-destruct” if it tries to “build up issues that don’t exist in the public mind,” the Houstonians correctly perceive that conservatives will always have an uphill fight if they let liberals define what the public issues are.

The problem is that when they do try to take the initiatives, they pick the wrong time or the wrong place. One such occasion was George Bush’s 1970 Senate race against Lloyd Bentsen. The Houstonians demanded that the state convention insert a platform plank supporting right-to-work, even though no one had the least doubt that Republicans favored it. The presence of such a plank, however, would have upset Bush’s fine-spun strategy of winning labor liberals disaffected by Bentsen’s primary victory over their favorite Ralph Yarborough. To this day, Houstonians continue to grumble about the way John Tower (at Bush’s personal request) forced them to abandon “principle” for such “pragmatism.”

The two wings quarrel endlessly, and unproductively, about who has elected the most Republicans or supported them the longest. Each lost a congressional seat last time to a liberal Democrat. Dallas, however, comes out ahead in patronage and in party control; at one point in 1975, the state chairman and both national committee representatives lived there, and until the Reagan sweep turned things upside down, there had long been a distinct Dallas outlook on the State Republican Executive Committee.

Tower, as titular head of the Texas party, sides with Dallas by instinct and by choice. “There is an exclusivity to Tower and his friends,” says James Lyon, a Reagan delegate, who as chairman of the River Oaks State Bank can hardly be characterized as a stranger to the establishment. “I don’t know that it is even a conscious thing. They enjoy each other’s company, they like to raise funds, they are movers and shakers in their own fields, but they don’t have the ability to identify with the grassroots.”

Tower’s aloof manner greatly amplifies the problems resulting from his friendliness with the Dallas wing. “If he had a whole lot of endearing personal qualities to go with his pragmatism, he’d be OK,” says a top Washington party politico. “He’s a little cold to a lot of people,” says a Republican fund raiser from Houston, who goes on to deny that shyness should be an excuse: “It’s not as necessary for him to be lovable as it is to be courteous, appreciative, and responsive.” Polly Sowell of McAllen, the party vice chairman under the old regime and the new, contends that “a lot of his problem is that he doesn’t remember names. The solution to that is simple: have someone whisper them into his ear. There are all these little county chairmen who work so hard and don’t get much recognition for what they do. One of the things they’d like is for the Senator to remember their names. They’d like to be able to say over a cup of coffee, ‘John Tower called me today.’ But he doesn’t do that kind of thing very well, and he doesn’t like to do it.” In the judgment, widely shared, of a Houston leader, Tower’s relationship with the party activists who do the pick-and-shovel work is much worse than with the rank and file who simply vote Republican and “don’t expect him to remember their names.” Polls show Tower with a consistently high rating, but because party workers—anywhere—tend to include a disproportionate number of ideological enthusiasts, the combination of Tower’s pragmatism and his personality has done him great harm. He feels the brunt of an intensely personal resentment that someone like Alan Steelman, who is equally “pragmatic” but far more affable, escapes.

Foolhardy, therefore, seems the word for Tower’s decision to identify so closely with Ford that he turned the Texas primary into a vote of no-confidence in himself. The defeat showed the thinness of the loyalties he could command, and he knew it. A niece who saw him afterwards described him as “just crushed. He looked twenty years older.” Having made his bed, he lay in it, and spent the next three months doing everything he could to overturn what the majority of the Texas Republican voters had wanted. John Leedom, a Dallas city councilman who served as a Reagan delegate, perceives “an inclination towards quarantining” the Reaganites in Tower’s post-primary behavior. “He should have said, ‘Mister President, my state has spoken, and I am with them.’ Instead he went and lobbied the Mississippi delegation and everything else.” One can grant Tower the courage of his convictions—“history will call that his finest hour,” says one admirer—but by pushing Ford so defiantly he recklessly diminished his influence within his state party.

The Ford-Reagan debacle is emblematic of the fundamental lack of rapport between Tower and Texas Republicans. Under his fifteen-year stewardship, goes the charge, the party has failed to expand and prosper as it should. Specifically, Texas has failed to become a two-party state. Criticism and defense of Tower on this score cut across the usual Dallas-Houston lines, although the sharpest dissatisfaction is voiced in Houston.

Stewardship is the right word to describe Tower’s relationship to his party—or was, until the Reagan revolution turned everything around. He takes an intense, detailed interest in party affairs, but he has left the day-to-day decision-making to a succession of handpicked, loyal followers strategically positioned within the party hierarchy. “They are the final authority on lots of things,” says a leading Republican activist, “but they also know that if they are troublesome, Tower will just pull the plug on them.” The party machinery has been weak—purposely so, critics say—and until lately there has been a revolving-door aspect to the jobs of executive director and state chairman. Ultimate power has been shared with an in-group that has included, at various times over the years, Peter O’Donnell, Anne Armstrong, Beryl Milburn, William Rector, and a few others. Tower’s role is that of senior partner—a first-among-equals who refrains from throwing his weight around. Friends have seen the brassy Armstrong “really chew him out” over a vote she didn’t like, “but he fought back; he wasn’t subservient to her.” The existence of this in-group has been a source of friction for years, with critics citing it as evidence of Tower’s high-handedness in directing the party. Peter O’Donnell, who retired from active party involvement in 1972, thinks it is little more than a case of Outs wanting in. But Tower friend State Senator Betty Andujar of Fort Worth sent out a pre-convention appeal (on “Hutchison for Chairman” letterhead) which spoke volumes to the contrary: It portrayed Hutchison’s fourteen-month tenure as “the first time in history” that the party had been “run in a completely open and just manner,” and thus seemed a tacit admission that the critics had long been right.

Considering the expansion of Republican strength across the South and West, during the Nixon years, there is little doubt that Texas Republicanism is not all it could have been. Tower’s critics blame him for it. A Houston leader says the statewide party is “insignificant” because of leadership decisions “for which Tower is directly responsible. He has used his position not to serve his philosophy but his power.” Hank Grover, the Houston businessman who narrowly lost the governorship in 1972 and blames Tower for his defeat, echoes a common chord when he says, “Everything is aimed at not electing anyone except John Tower. All he’s ever been interested in is his own reelection.”

The Republicans held not a single statewide office (except Tower’s) in 1961, and they still don’t. They held one of 22 U.S. House seats; now they hold 2 of 24. In the state Legislature, they now have 3 of 31 senators and 17 of 150 representatives. They hold 19 of 1016 county commissioners, 8 of 254 county judges, and 5 of 254 sheriffs. Tower and his supporters blame this paltry showing on a succession of bad breaks.

“A set of fortuitous things happened,” says Tower. “In ’62 we came on strong. John Connally only beat Jack Cox by 847,000 to 715,000. Then came Kennedy’s assassination and Johnson’s ascendancy. That wiped us out in ’64. Then in ’66 we started bouncing back. We elected Bob Price up in the Panhandle, George Bush in Houston, and Jim Collins in Dallas. We were coming back. Then, after ’72, Connally came over. We had identified a number of Democrats in the state that were just about ready to switch. This would have been the fruition of all of our efforts. And then”—his voice fell—“Watergate got us. I think we were just victims of circumstances.”

There is a degree of truth in this official history; it was difficult to build the party with a Texas Democrat sitting in the White House. And Republicans spent much time removing obstacles placed in their path by the Texas election laws. But the basic reason Texas is still an overwhelmingly Democratic state lies in the “trickle-down” theory devised by Tower and his closest associates. Concentrate on top-of-the-ticket politics—the presidency and the reelection of Tower—they decided, and the rest will follow eventually. Republican strength will trickle down from the major offices to the lesser ones. The theory is the antithesis of that used with such success by Mississippi party chairman Clarke Reed, who built his thriving party up, step-by-step, from the local level, and has far more to show for it than Texans have for theirs.

“Sure he’s a team player,” says a GOP candidate. “But that only applies to the team from him up—not from him down.”

In the sixties, there was a definite reluctance to commit the party to challenging certain Democratic officeholders. No serious effort was mounted for the governorship in 1966. “In those days,” says a Republican insider, “there were Democrats in the congressional delegation you could go after, and other’s you simply couldn’t. [Richard] White and [Bob] Casey were fair game, but [Jake] Pickle and O. C. Fisher were verboten.” Even today, he says, the party leaders “have the same operating mode, but more by force of habit than by calculating intent.” Against Tower’s wishes, San Antonian Doug Harlan took on Fisher in 1972; the senator cold-shouldered him. Tower, campaigning for his own reelection, showed up in the district praising Fisher; later, he prevented Harlan from introducing him as scheduled at a San Angelo rally, so infuriating local officials that they removed all Tower’s signs from the Tom Green County Republican Headquarters and kept them down until election night.

Tower’s support, or lack of it, for other Republican candidates is much disputed, and too complex to sort out here. The basic outlines are these: he plainly did nothing to help Grover in 1972 and privately was glad to see the Houstonian’s campaign squelched; Grover was so mistrusted by the Dallas wing that some lifelong Republicans voted the Raza Unida ticket against him, and one Dallasite described Tower’s behavior as “an act of statesmanship.” Tower recruited Paul Eggers out of nowhere in 1968, then shut off the money when Eggers decided winning might be fun. He did help Eggers and Bush in 1970, though not so much as either might have wished, and he stumped for Jim Granberry in 1974. He tried to discourage Alan Steelman from running against Bentsen in 1976, even after Steelman made clear he was planning to retire from the House regardless. One leading Republican with a long memory says Harlan’s second race (in 1974, after Fisher had retired) was “the only time I remember Tower giving full and total commitment” to a party nominee. “Sure he’s a team player,” says one unhappy former candidate. “But that only applies to the team from him up—not from him down.”

Tower is visibly hurt by criticism of his Texas performance. “I reject the notion that I haven’t worked to build the party,” he says. “I have.” He cites his support of gubernatorial candidates “every year I was not running myself,” and adds, “I’ve been active in individual state legislative races—when they wanted me to be—in county races, and all the way down.” The Grover affair is as sore a point with him as it is with Grover. “A lot of people are sore because Hank Grover didn’t get elected in ’72, and they blame me for it—why, I don’t know. I was busy running my own campaign. I didn’t do anything to Hank. They say, ‘Well, you got all the money.’ I raised my own money—the party didn’t raise it for me. I don’t know what else I could have done.”

And that’s the problem. What his critics question most are the degree of his enthusiasm and the manner in which he offers his help. “He never takes a leading role; he only responds, and you have to beg him,” says a former candidate. The party has done little to recruit attractive candidates and give them the kind of public exposure that was possible under eight years of a Republican administration; useful patronage has gone to influential contributors more often than to potential future party leaders. Little effort has been made to train a cadre of workers with campaign skills and find them decent jobs in the political off-season, leaving the party with a shortage of experienced managers when elections roll around. The party still projects a “closed door” aura. “Tower wouldn’t object to having any of these things done,” says one sympathetic critic, “but he wouldn’t initiate them either. He wants to get reelected, and all the rest doesn’t really matter as long as things are safe and OK, and OK people are running things. Don’t rock the boat.”

Thoughtful members of the party credit Tower and his “pragmatism” with saving the Republicans from what they fear would be a Houston-led suicidal fling. But at the same time, they fault him for stifling the normal development of a broad-based, moderate leadership. Were he to share party control freely with men like Bush, Eggers, Steelman, and Hutchison, the result might well be a party image open enough and temperate enough to compete successfully with the Democrats. As things have stood, he has given the moderates a choice between himself and chaos.

Tower’s constant concern over his control of the party, and his much fainter concern over its growth, puzzles those who want to understand him rather than deplore him.

Dallas Councilman Leedom thinks “it’s understandable that he’ll want to have a hand in the party organization,” but once that has been accomplished, “he ought to relax his grip.” Why doesn’t he? Most of the answers offered are personal. One friend thinks he is preoccupied with the fear that the Texas party might fall into the hands of “the radical right, who might embarrass him by association”—exactly as the Texas Reagan delegates did, hooting and kazooing and taunting the First Family down there below Sky Suite H. He may think that only the utmost effort to preserve control can save him from such humiliations. Another friend, now somewhat disillusioned with Tower, thinks he is less concerned about losing power than prestige: “He’s not mean, vindictive, or cruel like some politicians,” he says. “But he has a deep-seated insecurity that makes him not want any competitors because he thinks he might suffer by comparison with them.” Whatever the reasons, the chief result of Tower’s party stewardship has been to protect himself.

For the first time in eight years, Tower will soon be an adversary rather than an ally of the man in the White House. He expects to play a bigger role in opposition than he did the last time. Not since Kennedy has he had the chance to be a freewheeling critic of the chief executive, and he plainly is unfazed by the prospect.

The post-election reshuffling of Senate committees will enhance his power, though exactly in what direction is still unclear. If Strom Thurmond opts to move into the vacant ranking Republican spot on the Judiciary Committee, Tower can choose between taking Thurmond’s place as ranking Republican on Armed Services or retaining his present ranking position on the Banking Committee. The likelihood is that both Thurmond and Tower will move. That would not only bring Tower’s Armed Services title more in line with his performance, it would also position him to act as one of the party’s top spokesmen on international matters, since Clifford Case, the New Jersey Republican who is ranking member of the Foreign Affairs Committee, stands well to the left of the party’s viewpoint. Regardless, Tower plans to redouble his efforts to make the Republican Policy Committee a leading source of criticism of the Carter administration. As its chairman, and therefore the number three man in the party’s Senate leadership, Tower may be more visible than ever.

The immediate pleasures of helping lead the Loyal Opposition should be satisfying. But the long-run prospect is surely less so. Consider Tower’s predicament. As recently as five years ago, when the Nixonian Southern strategy showed promise of succeeding, Tower could dream of being a committee chairman under a Republican president in a Republican era lasting, perhaps, for decades. Now he must face the fact that the Democrats will control the White House for at least four years, and very likely for eight or more. In Congress his party, far from rallying from its post-Watergate slump, actually lost a few more seats. Only a giddy optimist, which Tower is not, could envision gaining control of the Senate in the foreseeable future; and he cannot be a chairman, much less majority leader, until then. His hope of being minority leader has just fizzled. He is not going to be president of the United States, and he is not headed any higher in the Congress either. At home, a sizable faction of his party actively dislikes him; and he must share power and prestige with John Connally. Though Tower has accepted Connally’s presence in the party with cordiality, good grace, and a notable lack of jealousy, there is no escaping the fact that Big John is a far more charismatic, politically dominating person who is unlikely to let Little John have his way as consistently as Little John likes to have it.

In many ways, Tower seems to have gone about as far as he can.

At the end of his current term Tower will be 53, an age at which most men look forward to ten or fifteen more years of productive activity. Though every indication is that he plans to seek reelection—he himself said last month, “I have no intention of not running,” which is not quite the same thing—there are still several Republican insiders who doubt he will. A congressman’s salary of $42,500 is not much inducement for someone like Tower, who enjoys the good life and whose contacts in the world of corporate business could quickly produce a job that would let him live it. He came to politics from a low-salaried professorship, and the Senate has required its members to cut back on the honorariums he used to supplement his income generously. If he ever plans to make money, time is running out. The combination of his Navy duty and his Senate tenure will be just enough, in 1978, to qualify him for Congress’ generous retirement benefits for twenty years’ service. Might he use them? A Washington Republican who has known Tower for years observes that “the Hill is not a very attractive life after a while. Too many people monitor everything these days. The visibility of public life is increased and the workload is overwhelming, especially in a big state like Texas.” A record number of congressmen retired voluntarily this year, many of them saying, in one phrase or another, “It just isn’t any fun anymore.” Tower has not been immune to this. “I’m sorry to see the decline in respect for the institution [of the Senate] on the part of younger members,” he says. One of his young relatives remembers him as “a much warmer person” before he became preoccupied with the problems of politics, especially those of recent months. Tower thrives on politics, of course; he loves its challenges, intrigues, and perquisites; it has been his life. But he is more than just a political animal. Nineteen seventy-eight seems to be the year when he must decide whether to commit himself to politics as a lifetime career, provided he can manage the necessary reelections, or whether to do something else; after another term, he will be nearly sixty. For his part, Tower simply suggests that the normal career timetable doesn’t apply to him; his family is very long-lived, he says, and he’s in excellent health, so he has plenty of time for those other options. “But I’m not going to hang around the Senate until they carry me out feet first.” Assuming Tower does run, he may continue the amazing streak of good luck that has let him make every race since 1961 in an auspicious year for Republicans. “Nineteen seventy-eight is made to order for a Republican comeback,” says a high-level party strategist. “If we don’t come back in ’78, that’s it. We can’t go on.” Those close to Tower expect him to spend the next two years making a name for himself as “a bulwark against Carterism”—a label in search of a concept if ever there was one. Tower speaks with fervor against big government—“this massive federal bureaucracy, this cold impersonal monster”—and he is gearing up to be the spokesman for what he perceives as Texas’ interests against any lack of sympathy emanating from the White House. Neither Briscoe nor Bentsen can do that. If the cards fall right, says a close friend, “he’ll be convinced he’s doing something for Texas of historical significance, and that will encourage him to seek reelection.”

Tower’s badly strained relations with Texas Republicans paradoxically do not translate into prospects of serious trouble in the 1978 party primary. He is more secure than he looks. Hank Grover, Tower’s archenemy whose presence in the race would guarantee fireworks, seems disinclined to run. John Connally’s name has been suggested by some who think he needs a political base for his presidential ambitions, but Connally is unlikely to see much merit in being a freshman anything—except president. Several other names have been bandied about—Phil Gramm, the articulate Texas A&M professor who ran a weak race as a conservative Democrat against Lloyd Bentsen; Ernie Angelo, the popular mayor of Midland, a Reaganite who sides with the Houston wing; Dr. Ron Paul, the arch-conservative former Lake Jackson congress man; and Ray Barnhart, the Harris County Republican chairman and leader of the Reagan delegation at the national convention.

But no foreseeable primary opponent could, if nominated, go on to win a statewide race; and any losing challenge from the Right would probably strengthen Tower in the general election. His voting record is his ultimate protection; even his worst enemies within the party cannot find fault with that. They’d love to see him beaten, but they’re afraid of what would happen if he were: a Democrat is unthinkable. “The Republicans will work for him again,” says a Houston leader, “but not with heart.” The other primary should be a free-for-all; Tower is the inevitable quarry for hungry Democrats. Joe Christie, a likable former state senator from El Paso who has chaired the State Board of Insurance for the past four years without antagonizing the consumers or the companies, is a sure bet to run. Bob Krueger, the erudite New Braunfels congressman, has been traveling around Texas making speeches, which he follows up with a flock of personal thank-you notes: a sure sign of a politician whose ambitions reach outside his district. East Texas Congressman Charlie Wilson, a superb campaigner who could be Tower’s strongest opponent, seems too happy now with his safe seat and a slot on the House Appropriations Committee to risk losing them. Houston Congresswoman Barbara Jordan’s name is usually mentioned but she usually has a knack for playing her strongest card—and for a black woman, even in 1978, a statewide race in Texas is not it. Barefoot Sanders, the Dallas attorney Tower defeated in 1972, may try again, though the prospect of success appears dim. Houston Mayor Fred Hofheinz and Land Commissioner Bob Armstrong, both young attractive moderates, could also wind up in the race, as could Attorney General John Hill.

Whomever the Democrats pick will find Tower no pushover. He has been campaigning quietly but diligently since 1972—a marked change from his earlier habit of letting things slide between election years. His strength in normally Democratic territory, especially the rural areas, should not be underestimated. He has not actively antagonized nearly as many people outside the Republican party as he has inside. As late as last October, statewide polls were showing him with a 2.5 to 1 approval rating. The race will be a lively one and in it we will find out what Carterism really means.

If Tower doesn’t run, or loses in 1978, and if for whatever reasons he decides not to go after a well-heeled business job, what else could he do? He is neither an administrator nor executive type, and his friends think any return to teaching would be “incredible.” Ken Towery, his top aide in the sixties, thinks he’d have no trouble keeping himself entertained. “There are lots of things he has never had time to do. Learn to fly a plane, for example—he’s always wanted to do that. But you know what he’d really do best is be a television news analyst, sort of a conservative Eric Sevareid. TV could use somebody as articulate as he is, with his viewpoint, and he’d love it.”

Told of that, Tower just grinned. But his eyes sparkled. Here with tonight’s commentary. . . . “Tex” Tower would have come along way.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Senate

- Longreads

- Ron Paul

- John Connally