This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

It has been eight crazy years now, but I can clearly remember the night when the movie and I first arrived in Hollywood. As a result of that trip, we actually lived there for a time under studio contract: I lasted a year or so, while the movie remained as hostage for a few more years before I could ransom it back to Texas. We have also returned occasionally since then—and more often this past year for fetes and meetings, now that the movie is finished—but I always feel awkward.

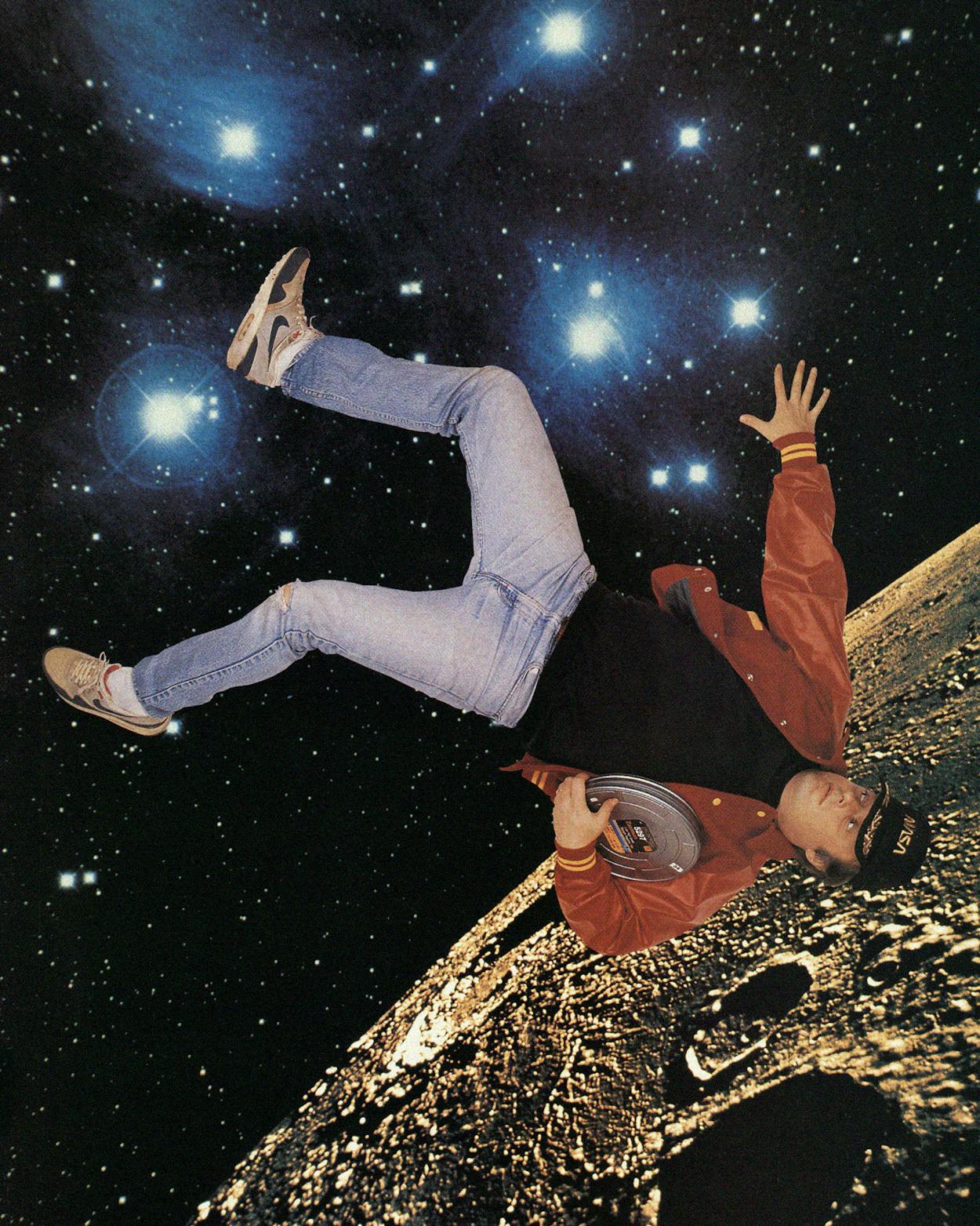

The movie and the town come from worlds so separate that there is almost no common ground. The film came mostly from outer space, shot out there by extraterrestrial beings—human beings, as it happened, but very different from the Hollywood sort. These humans had a less inventive, much more literal camera eye, but they shot scenes only God could have created; they were on location at the direction of the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

The movie, which consists entirely of NASA footage, depicts real life, not at all the kind of film that Hollywood creates. Hollywood movies, when they work, are illusions that suspend our disbelief and touch our hearts. This movie is pure reality and shared emotion that, when it works, transcends belief. It is about the experience of the first human beings who physically left our world to go someplace else: the 24 Apollo astronauts who traveled to the moon between 1968 and 1972.

Hollywood movies are works of imagination and careful artifice, whereas the movie I carried to Hollywood is totally artless. Going to the moon was itself a work of powerful imagination and high art, and the movie was simply an afterthought. I was not so much a filmmaker as an archeologist who excavated a forgotten relic, cleaned up the pieces, and fitted them together.

It was February 1982 and so late at night that it was really early morning when the red-eye from Houston touched down at Los Angeles International Airport, full of illegal aliens lugging crude parcels that contained everything important to their lives. The movie and I fit right in. Too nervous to check it as baggage—there was only the one copy—I had packed the movie in a Texas Ruby Red grapefruit box and carried it with me.

Nowadays there are lots of copies (prints, they’re called) in special reinforced cases (Goldbergs, they’re called), shipped by bonded couriers, but the movie has never fit so well in anything as it did in that recycled cardboard box. Although it is composed of the most expensive film footage ever shot by human beings, the movie itself is a product of the cinematic grapefruit leagues.

I grabbed a cab to the Chateau Marmont, a hotel allegedly on Sunset Boulevard that had been recommended by Jerry Jeff Walker, who said it was reasonable and convenient and had great room service. This proved to be partially true: The room service menu offered cheese, fruit, and cold-cut plates and a seven-page wine list. Only the neon sign was really on Sunset Boulevard, and even that was off by the time the movie and I arrived.

The reception area was dark and deserted when I stumbled into it. I could barely hear strange sounds coming from a half-lit anteroom at the end of the foyer. Abandoning my suitcase and my briefcase but still lugging the sixty-pound grapefruit box, I tiptoed in that direction. The sounds resolved into fierce grunts and curses as I neared. I peeked around the corner.

There, sword-fighting with two-foot-long candles, were Dan Aykroyd and John Belushi. Yep, I thought to myself, this is Hollywood, all right.

I honestly felt we belonged there, the movie and I. I knew it was horribly primitive by Hollywood standards: merely 16mm (as opposed to 35mm) film spliced together with tape and messy with grease-pencil marks (as opposed to hot-spliced and clean), and it had no sound effects or music, although it did have a wholly separate interlock sound track (as opposed to optical sound-on-film).

It was basically a garage movie, something that had been pieced together in my Houston living room. But I was sure that the legendary impresarios of Hollywood would see past those superficial, purely technical imperfections and perceive the movie’s content. And that, I knew beyond a doubt, was unique.

So I was confident, indeed, almost complacent in my belief that the movie would somehow find its way to the big screen, which was where it belonged. This was the only thing, I realize now, that I wasn’t totally stupid about.

I have never again seen Dan Aykroyd in the flesh, but for the next month I ran into John Belushi nearly every day in the garage of the Chateau Marmont. Waiting for his red convertible Mercedes to come up, he would pace around the valet area, muttering incomprehensible curses, his pupils as black and dilated as wide-open camera lenses. I knew he was staying in the bungalow just two doors down from mine—Tony Randall was between us—but I could never bring myself to say hello. We were neighbors only in a Hollywood sense.

By then I was a resident myself. With almost no help from me, the movie had found a home almost immediately. We were engaged to Columbia Pictures within three weeks of our arrival, although that didn’t become official until May, when we signed the formal contracts, which gave the studio the rights to the movie.

The matchmaker was Carl Sagan, who at the time was riding the wave of his life. His book Cosmos was the number one best-seller in the world, his Cosmos television series was an international phenomenon, and his star-struck cheer was a hit on the Johnny Carson show. A friend of a friend, Sagan fell for the movie as soon as he saw it. “Absolutely wonderful,” he gushed, “and verrry important.”

Sagan had not only influence but also the willingness to use it, a troublesome blend in an insecure town; he lasted barely a year in Hollywood. Before his departure, though, he called his best friend in the movie business, Frank Price, the president of Columbia Pictures, and persuaded him to give the movie serious attention.

Before I had even learned how to get there reliably, my name was on a parking space at Burbank Studios, the home of Columbia and Warner Brothers, the stomping grounds of Bogart and Cagney and Cary Grant, of Rita Hayworth and Barbra Streisand. The parking lot lay in the shadow of a four-story scaffold that supported a false-front Main Street that has been enlivened and immortalized in dozens of pictures. Here were the cobblestones that the Music Man danced over and the phony store windows that Robert Redford had pretended to peer through in The Way We Were.

Everything about the place was tangibly false yet compelling, resonant with cinematic memories. To walk that street was to lose oneself in the echoes of illusions. I found myself drawn there during lunch hours, doing just that. It provided reassurance that the fantasy I seemed to be living was rooted in real life, an actual Hollywood experience and not just a dream.

The spell lasted about a month, until the evening I returned to find the Chateau Marmont surrounded by police cars, TV-news vans, and a cheap mob scene. John Belushi had been discovered grossly dead around the time I had been strolling along that make-believe boulevard. He was one of the hottest stars in town—four years before, he had a number one record album, number one movie, and number one TV show, all at the same time—the day he died from a drug overdose.

I couldn’t go to work the next day. I stayed in bed, ordering room-service cold cuts and expensive Burgundy and watching the John Belushi coverage on television. Nobody from Columbia Pictures called to find out why I wasn’t there. That was my first day of true life in Hollywood.

The movie is called For All Mankind, a title that used to make me uneasy because it sounds so pretentious. You have to think pretty grandiosely to present your work as “for all mankind.” Nobody in Hollywood liked it, although not because anyone was worried about sounding grandiose. Columbia’s marketing division proposed Lunar Odyssey with the hope of fooling the huge crowds that went to see 2001: A Space Odyssey. I didn’t particularly like the idea, but I didn’t argue about it either. I had far more horrifying proposals to contend with.

The reason we eventually kept the title is that, unlike many suggested-in-Hollywood titles, it wasn’t just made up and stuck on the movie. “For all mankind” is a refrain heard throughout the movie, both integral and meaningful, reflecting its theme and its message. I didn’t invent the line; I stole it. The act of going into space is what was grandiose.

“We set sail on this new sea,” proclaimed John F. Kennedy, “because there is new knowledge to be gained and new rights to be won, and they must be won and used for the progress of all mankind.” Kennedy made this proclamation in a passionate speech to 100,000 citizens at Rice University stadium in September 1962. Houston’s KHOU-TV was there that day, filming Kennedy up close, in sharp focus and crisp colors. Afterward the station gave the film to the NASA Film Library, which over the years has accumulated miles and miles of remarkable footage in the cryogenic vaults at the Johnson Space Center. That was where I chanced upon the film seventeen years later.

I had come to the Johnson Space Center in early 1979 to research an article intended to coincide with that summer’s tenth anniversary of Apollo XI‘s historic leap to the moon. The American space program—NASA, in other words—was at the time adrift in one of its periodic doldrums. The last lunar landing had been in 1972, and the space shuttle was still in some problematic future. So the people at the Johnson Space Center had time on their hands and were amenable to long, relaxed interviews. It was the perfect time for a patient, generally curious journalist to show up. Tom Wolfe, for instance, had been there, hearing the stories that would lead him to his masterpiece, The Right Stuff.

Wolfe and I crossed paths every now and then and exchanged notes and letters, but our interests were fundamentally divergent. He was fascinated by the vivid personalities of the early astronauts—specifically the original Mercury astronauts—and wasn’t much interested in their experience of space travel. In his entire 436-page book, fewer than 30 pages are set in outer space, and half of those describe the adventures of a chimpanzee in orbit.

I, on the other hand, was bored by everything that had happened to the astronauts before blast-off. I would listen to detailed histories of every squadron they had ever flown with and stories about the local top guns and not even turn on my tape recorder.

Nevertheless I taped almost eighty hours of candid, often intense conversations with the Apollo astronauts, the first extraterrestrial humans. When the interviews were at their best, we went back “out there.” What was really significant about the Apollo program was not landing on the moon; it was leaving Earth—daring to go somewhere else—that was truly meaningful. The moon is just the first place you stop. That was the major lesson I learned from the men who did it, who spent every spare moment looking back at the wondrous planet they had left.

I tried to express what I was learning in an article (see “Moon Struck,” TM, July 1979) published on the tenth anniversary of Neil Armstrong’s curiously anxious (“one small step for [a] man”) yet triumphant (“one giant leap for mankind”) watershed footstep. The article was gratifyingly well received, and the response was all the encouragement I needed to press ahead with a movie version. The film, I knew, had already been shot. NASA had sent those men into outer space with movie cameras that they instinctively reached for whenever they saw something astonishing or simply beautiful, which was frequently.

Thanks to Don Pickard, Jr., I was able to see what the Apollo astronauts had seen. Pickard—an amiable, naturally laid-back sort whose favorite pastime is camping on secluded Gulf beaches—is the senior film editor at the space center. He has worked there since 1965 and has seen every foot of film that has come back from outer space.

In a room half the size of a basketball court in Building 2 are film cans stacked seven feet high. They contain nearly six million feet of 16mm film, which is available for public viewing. Anybody can ask to look at, say, roll 7334. It would take more than two thousand hours to look at everything in the film library; so to save time, Pickard had assembled a dozen rolls containing the most famous, most obvious shots—NASA’s greatest hits. We spent a whole afternoon screening this collection, more time than most people are willing to spend on film research.

The flight footage in the NASA Film Library is a national treasure, pure and simple, as irreplaceable as the Sistine chapel. It was shot on a film stock selected especially for use in outer space, and it returned to Earth only when and if the astronauts were able to. As soon as the capsule was hoisted onto the recovery carrier, Navy technicians would reach inside for the film magazines and divide them into two pouches—so not all of the film would be lost if a plane went down—and the carrier’s two best pilots would fly them directly to the Johnson Space Center. There, the film was carefully processed and developed in a lab in Building 8, and print masters were made for public use. Then the original magazines were sealed into vacuum cases and locked up in a supercooled, lightproof vault.

I was the first fool who walked in and said, “I want to see it all.” Don Pickard took me at my word, became my guide, and never complained about it. I think he was happy to have somebody to show the film to. I rarely looked for anything in particular; I just reacted to the stunning footage and noted what most impressed me.

The most spectacular footage, to my mind, is the view of sunrise from the earth’s orbit. In these sequences everything is black outside the spacecraft window. Then for an instant, along the horizon, comes an arc of ultraviolet light, which you can’t exactly see. Suddenly a hot violet wire appears on the curved horizon, vibrantly expanding into purples and cobalt blues, swelling to a burst of perfect spring green before descending through the spectrum into brilliant golds and incredible reds. It is pure sunlight refracted and filtered by thin air, the earth’s very breath, framed in endless velvet blackness. It looks like a rainbow at midnight, and it lasts only a moment before actual sunrise blinds you.

My instinctive reaction to the footage was: Why has this stuff never been on the big screen? We have all seen some of the excerpts on television, mostly the same shots over and over again, cut together haphazardly and usually smothered in florid rhetoric by some air-hog anchorman. I had been surprised by how many of the astronauts had volunteered lyrical memories of the orbital sunrises they had seen. I found myself wedding the verbal memories from the astronauts to the visual memories captured by their cameras—the same moments, sights, and events. By doing so, I glimpsed scenes of the movie that existed, buried under years of forgetfulness. It struck me as a film that was long overdue.

The movie I pictured inspired a handful of investors—all of them Texans. None of us knew the slightest thing about filmmaking or the movie business, but the federal government had already done the difficult, expensive part. The American people had spent $42 billion to hire the cast and crew, build props, scout locations, rehearse, and shoot. We were just going to ice the cake. I figured it would take two years and $500,000, tops.

Two days before Christmas, 1979, we chartered a small corporation and opened a bank account. Most of our start-up capital was spent on the largest, most complicated film order in NASA history, which took more than five months to fill. We acquired cheap 16mm work prints of some 25 hours of Nasa’s film—about one percent of the archive, but the heart of it—which we planned to fashion into 90 minutes of true-life adventure movie.

We rented a roomful of editing gear and installed it in my living room, hired a couple of guys who knew how to operate it, and went to work. Editing was slow going. The miles of wondrous footage had been shot, after all, at random and under extreme conditions by two dozen cameramen over several years. It was a chaos of fantastic imagery that yielded a form only grudgingly and never predictably.

That form was provided by the firsthand accounts of the 24 men who went to the moon on nine different Apollo flights that were, in essence, all the same journey. The right chemistry of their words and those pictures would offer an immediate, intimate, out-of-this-world experience. Finding the right chemistry, however, was no easy trick: We had 80 hours of verbal memories and 25 hours of visual memories to mix and match. Many a day led to nothing but frustration, film cans hurled across the room, and muttering retreats to the local bar.

When we first ran out of money, we had maybe fifteen minutes of a rough cut. We did what we ended up doing every time we went broke: We screened what we had for anyone willing to look at it, and I sold investors a few of my own shares. It was a wildly inefficient, nerve-racking way to run a business, but it never failed. The movie always rescued the company.

For two years we worked in fits and starts, splitting time about two to one between raising money and making the movie. At the end of that period, we had about twenty additional investors and a 150-minute rough cut. The movie portrayed the experience of leaving Earth in the first person and in the present tense for the first time, a real-time capsule of a timeless event. This was the movie that I had packed so carefully in a Texas Ruby Red grapefruit box and carried off to Hollywood, where grandiose dreams are everyday stuff.

It had never occurred to me that For All Mankind was a documentary until we went to Hollywood. I had always just thought of it as a movie. That’s how naive I was.

Our marriage to Columbia was doomed. But I was too relieved and dazzled to see it, and so was the studio. Columbia promised to spare no expense in polishing the movie, to make it the best documentary ever to come out of Hollywood. Marvin Antonowsky, the worldwide vice president of marketing and distribution, announced to me with appalling glee that Paul Newman had agreed to narrate the movie. Antonowsky was so pleased with himself that he almost looked benign. I was horrified.

Now, I like Paul Newman. But I couldn’t imagine a thing he might say about leaving Earth or going to the moon that wouldn’t be empty words. We already had eighty hours of firsthand we-were-there talk from the astronauts. A narrator is the central ingredient of the standard documentary formula, though. Developed for television, the formula calls for an all-seeing, all-knowing explainer of things. That’s how TV newspeople think of themselves, and they are responsible for most of the documentaries made in America.

By Columbia’s lights, of course, the studio was only trying to do right by us. Hollywood’s formulas are time-tested, and studio executives are sworn to uphold them. I could tell that my lack of enthusiasm caused Antonowsky real pain, which I didn’t think was possible.

The depth of our misunderstanding came home to me when Columbia dispatched Tom McCarthy, the senior vice president for postproduction, to the Johnson Space Center. His mission was to determine how to blow up the film from 16mm to 35mm, a technical feat that had never before been attempted with NASA’s film, but one that was crucial to the movie.

Now, I liked Tom McCarthy too. He was the only Columbia executive who never misled or patronized me. He had been the original editor of Gunsmoke, and he was full of riotous Irish tales about television’s golden age. But he no more had a clue about For All Mankind‘s inherent value than Festus would have.

Because of NASA regulations, the film footage taken by the astronauts cannot leave the grounds of the Johnson Space Center; most of it seldom left the vault. You can’t make a quality blowup from a copy, however. NASA itself had tried, with poor results. We needed to have access to the originals.

So Tom McCarthy, aglow with Irish charm, walked into a meeting with NASA’s top ten film experts and told them that he would take it all off their hands. They could give those magazines to Columbia Pictures, and he wouldn’t even charge them for shipping. It was stupefying. And a very short meeting.

I suppose it was pure good luck that Coca-Cola bought Columbia Pictures in the late summer of 1982. The new administration regarded the film and me askance as a pet project of the previous management and put us on a far back burner. There is no telling what For All Mankind might look like today or what it might be called if that had not happened.

At the time, though, the change in ownership was disastrous for our Texas business. The investors hadn’t gotten a nickel back yet, and we didn’t even own the movie anymore. We would have been sunk if not for the barrels of goodwill that the movie had earned among filmmakers who, unlike the studio suits, weren’t beholden to convention.

I sold the last of my stock to stake us, and we rented space in a B-movie editing complex, where our neighbors made cheap horror and slasher movies. It was a big step down from the Burbank lot, but it was all ours. We were happy there, for a while.

For some time we had been running on dream power and petty cash and were close to burnout. But the final blow was delivered, naturally, by lawyers. In early 1983 we filed for divorce. Columbia’s response to our request ran seventy pages long, with little up-yours clauses and requirements—and a bill for its services.

I came home to Houston angry and depressed, to get drunk and mope and to recover my bearings. I swore to myself that I would never again set foot in Hollywood. Old friends, to whom I had foolishly bragged about my parking space, would ask me about the movie, and I would just glare at them. I went back to writing for a living, hoping to rise from the poverty I had sunk into. For almost a year I tried not to think about the movie, and sometimes I succeeded for a week or so.

The movie itself, for the most part, had remained in Hollywood as security against our debts—crated up in storage someplace, buried away. All I had were the forty minutes of the recut rough cut that we had begun polishing on our own. I kept it in a grapefruit box in the trunk of my car.

Every couple of months we would go to the media center at Rice University, rustle up a roomful of strangers, and show them our sample of the movie-that-could-be. The investors we found in this way were not rich people looking for tax write-offs. Easier write-offs were plentiful in Houston, and most rich people were too busy to attend our scruffy screenings. Instead, we ended up with people who rallied to the movie for its own sake, whether investing was wise or not, whether they could really afford to do so or not.

We bought the movie back from Columbia Pictures for $60,000 in June 1986. I had a catch in my throat when the crates arrived (C.O.D.) from Hollywood, and I tore them open like a six-year-old at Christmas. We were back in business. No longer were we in the movie business, though. We were strictly in the For All Mankind business.

We concluded a contract with NASA, the key provision of which was that none of the footage could leave Building 8, but we did receive access to the originals. Our experts and NASA’s reckoned it would take three months to blow up our ninety minutes of film.

Blowing up footage from 16mm to 35mm means exposing the former, through a lens system in an optical printer, to the latter. We had purchased a rare, specially designed lens package from Nikon and installed it in the ancient 1930’s-model printer in Building 8. We attached a microscope that could focus to molecular planes of the film emulsion, a wet gate to advance the film so that it would never be touched by mechanical parts, and new color-balanced lights. We spent six weeks just testing and calibrating the gear.

NASA, meanwhile, began exhuming the original 150-foot magazines. It took 24 hours for each roll to thaw out, and only three rolls were brought out at a time. We exposed the frames one at a time, rebalancing and reframing as we went, averaging four or five shots a day (the finished movie contains nearly seven hundred shots). It took us a year and a half to complete the job.

For All Mankind made its big-screen debut on January 21, 1989, at the U.S. Film Festival in Park City, Utah. Sponsored by the Sundance Institute (an organization founded by Robert Redford to give aid and comfort to independent movies), the festival is the premier showcase for independent movies in America. We barely made it. I was in the projection booth, cutting in the last reel half an hour before the movie was to start. At the end of ten days of screenings, For All Mankind won the grand jury prize for the best documentary and was also voted most popular.

We licensed the movie in Europe and Japan and, for the first time in ten years, actually generated some income—enough to clear our debts and even return a bit (a tiny bit) to the investors. But we struck out in Hollywood. There were offers for television and video rights, but nobody stepped up to distribute the movie to theaters, where we felt it belonged. A typical reaction was that of Michael Eisner, the chairman and CEO of the Walt Disney Company, who took the movie home one weekend to show to his family. “It’s really wonderful,” he reported. “But it’ll never make a nickel.” The documentary formula was at work once again. Just as Hollywood makes nonfiction films so boring that no one wants to see them, so too does Hollywood expect them to do poorly at the box office.

It was confusing and bitterly frustrating. All through the summer the movie continued to do well on the festival circuit—in Dallas, Seattle, Tokyo, Munich, and Montreal—attracting crowds and nice reviews and winning prizes. Yet distributors still passed on it, many of them for no better reason than the knowledge that others had passed before them.

Finally we decided: Screw ’em. We would take the movie out ourselves, at least in a limited test run to see if it was possible. We knew it would be difficult. The last movie to be self-distributed with any success was Benji back in 1974 (which had also been made by a gang of stubborn Texans).

On November 1, 1989, we opened the movie at five theaters in San Francisco, Seattle, and Rochester, New York. We had friendly support from theater owners, the movie got terrific reviews—four-star rave-ups from the local critics and “a very enthusiastic” two thumbs up from Siskel and Ebert—and it drew crowds. Paying crowds. For All Mankind was the top-grossing movie in Seattle for three weeks straight, despite playing in only one theater. In San Francisco it had a seven-week run in a theater in which Dead Poets Society had run for ten weeks, the house record.

The film wasn’t exactly Batman—but then we had never expected it to be. We were overjoyed just to prove to ourselves that the movie really had an audience and that we weren’t complete fools.

Theater owners were impressed. Pacific Theatres, one of the largest chains in Los Angeles County, offered its nine best houses for two weeks beginning January 19. One is the Cineramadome on Sunset Boulevard, a landmark theater in that tough, scornful town. It was an offer we couldn’t refuse, no matter how intimidating it was. So we decided to open in Texas the same day, just so the movie could play someplace we felt comfortable.

I really have no idea if the movie will make any money or not. For the sake of the investors and my wife, I certainly hope so. But for me, I got to watch my dream come true. The movie that I glimpsed in miniature, soundless, disjointed fragments on Don Pickard’s editing table is now playing before the world on the silver screen, with a score by Brian Eno in Dolby stereo. I know too that five hundred years from now, when people want to understand how it felt to leave Earth for the first time, they will dust off For All Mankind. And I figure that’s something to be proud of.

- More About:

- Film & TV

- TM Classics

- Space

- Longreads

- Filmmaker

- Documentary

- Houston